by guest contributor Frederic Clark

The history of reading has recently witnessed an explosion of interest, doing much to transform and reinvigorate the practice of intellectual history. Although recent histories of reading range across every conceivable genre and period, early modern Europe has played a starring role in the rise of this field of study. This is due above all to the fact that many early modern readers were prodigious annotators.

But we, with our taste for self-reflexive inquiries, are hardly the first to contextualize the acts of readers. Early modern annotators often obsessively detailed the circumstances of their reading—recording where and when they read their books, what other books they owned, and in turn what other books the authors themselves had read. Such annotations wove together an elaborate web, linking multiple books and readers to one another, while fixing each respectively in space and time. These meditations on reading facilitated the movement of books across continents and oceans, or through the generations of a single family.

One of the most famous of these annotating families transported their books from the Old World to the New. We remember this family—the Winthrops—for the outsized role they played in the politics of colonial New England. They were perhaps the first American political dynasty. But they were also a family of readers—obsessive annotators in precisely the fashion described above. And as they were so often in motion, so too were their books.

When we hear the name Winthrop, John Winthrop Sr. (1587/8-1649) likely first springs to mind along with his famous declaration upon approaching the shores of Massachusetts—namely, that he and his fellow Puritans had come to found a “city on a hill.” But long before there was a city, let alone a nation, there was a library. The Winthrops possessed many books: John’s father, Adam Winthrop (1548-1623), was a Cambridge-educated lawyer. Not a scholar by profession, he nevertheless moved in scholarly circles; for instance, every year he rode up to Trinity College to audit its finances. When he was not managing his lands or working in court, Adam reserved his hours of otium for books. He collected hundreds of them and wrote in many with a painstakingly clear and careful hand.

Adam died in 1623, seven years before his son set sail for Massachusetts. While he did not make it to New England, his books did. His already sizable library formed the nucleus of what would become a still larger collection. Although John Winthrop Sr. did not annotate the family books, his son, John Winthrop Jr. (1606-76) produced a quantity of marginalia that rivaled his grandfather’s output. In addition, John Jr.—who joined the family business and became governor of the new Connecticut Colony in 1657—acquired still more books. There is evidence that Adam provided his young grandson with direct personal instruction in the marking up of books. For Adam Winthrop did dictation for John Jr.—filling in the pages of an almanac in his voice—when the latter was just fourteen years old.

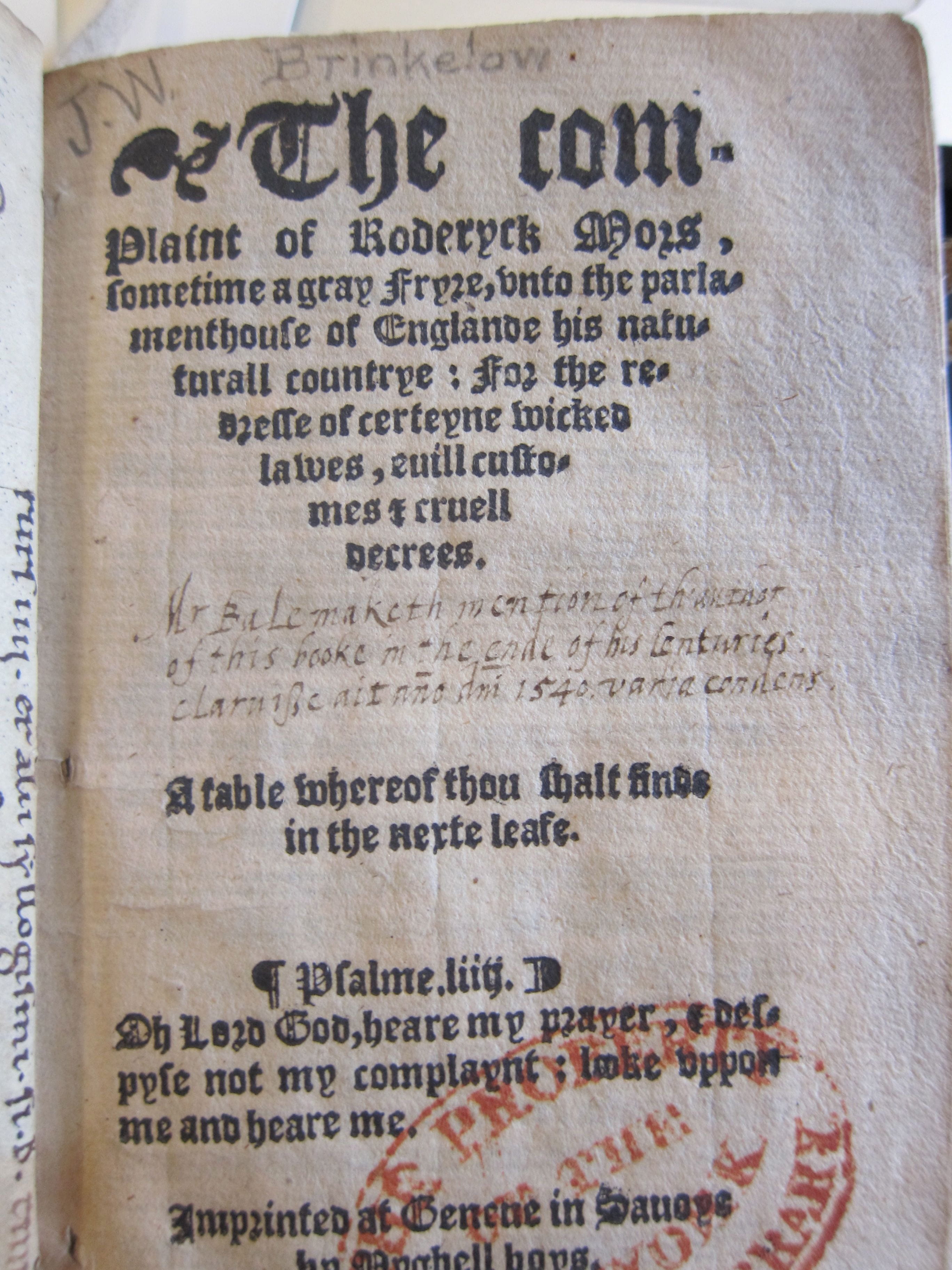

How did Adam, the family patriarch, annotate? He often began by fixing both a book and its author in context. He was aided in this task by the massive encyclopedic bibliographies of the sixteenth century, especially John Bale’s Catalogus of British writers. For instance, in his copy of the Tudor-era polemic The Complaint of Roderyck Mors, Adam discovered that Bale had identified the true author of this pseudonymous work as one Henry Brinklow. Accordingly, he wrote this out front and center on the title page, remarking “Mr. Bale maketh mention of the author of this booke in the end of his Centuries”:

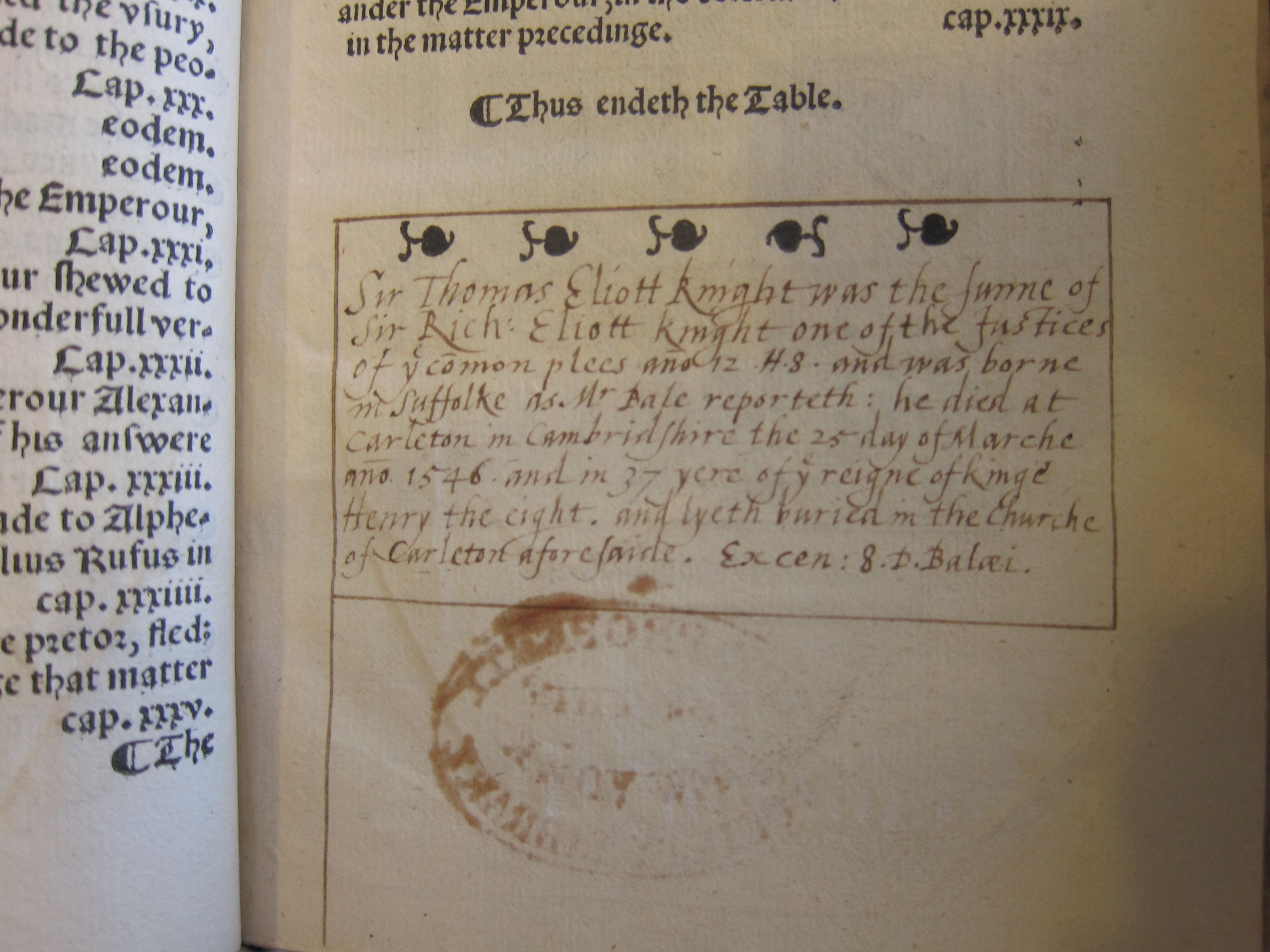

Here, in a neat little text-box he drew out at the end of table of contents in Thomas Elyot’s Image of Governance, Adam again turned to the trusty “Mr. Bale” for biographical details on Elyot. As he explained, “Sir Thomas Eliott Knight was the sonne of Sir Rich: Eliott Knight one of the Justices of the common plees anno 12 H.8 [i.e. in the twelfth year of Henry’s reign] and was borne in Suffolke as Mr. Bale reporteth”:

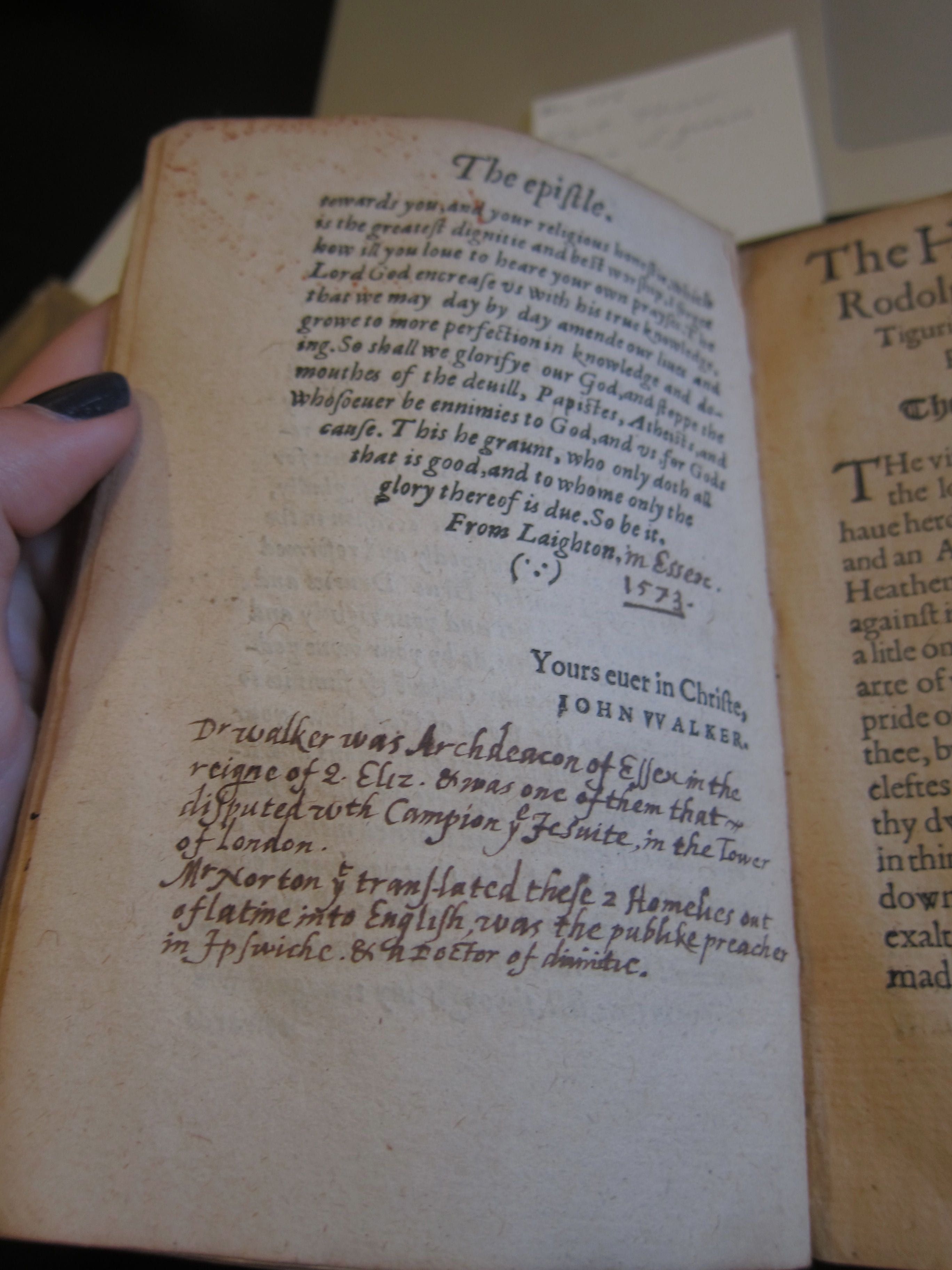

In other cases, Adam relied upon his own memory of England’s tumultuous religious politics when setting a text in context. When reading a collection of sermons prefaced by the English cleric John Walker, Adam wrote that Walker was involved in the events leading up to the 1581 execution of the Jesuit Edmund Campion: “Dr Walker was Archdeacon of Essex in the reigne of Q. Eliz. and was one of them that disputed with Campion the Jesuite, in the Tower of London.”

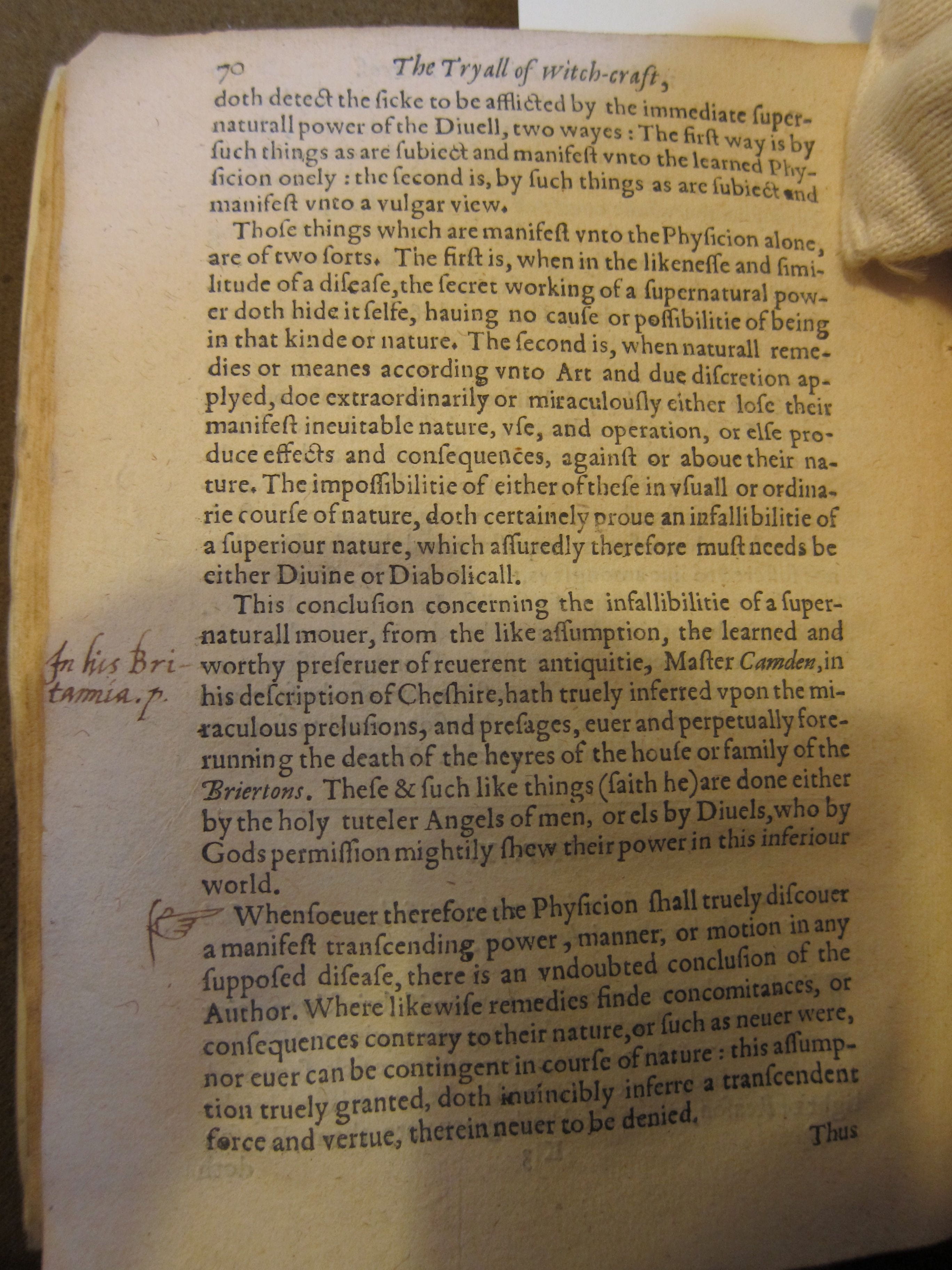

Reading for Adam was clearly a family affair. Consider the physician John Cotta’s Triall of Witch-Craft. John Cotta was Adam’s nephew, the product of his sister Susanna’s marriage to one Peter Cotta. Adam meticulously marked up his copy with cross-references to the many sources alluded to in the text. Here he prepared to add an exact page reference to William Camden’s Britannia, but then apparently forgot to do so:

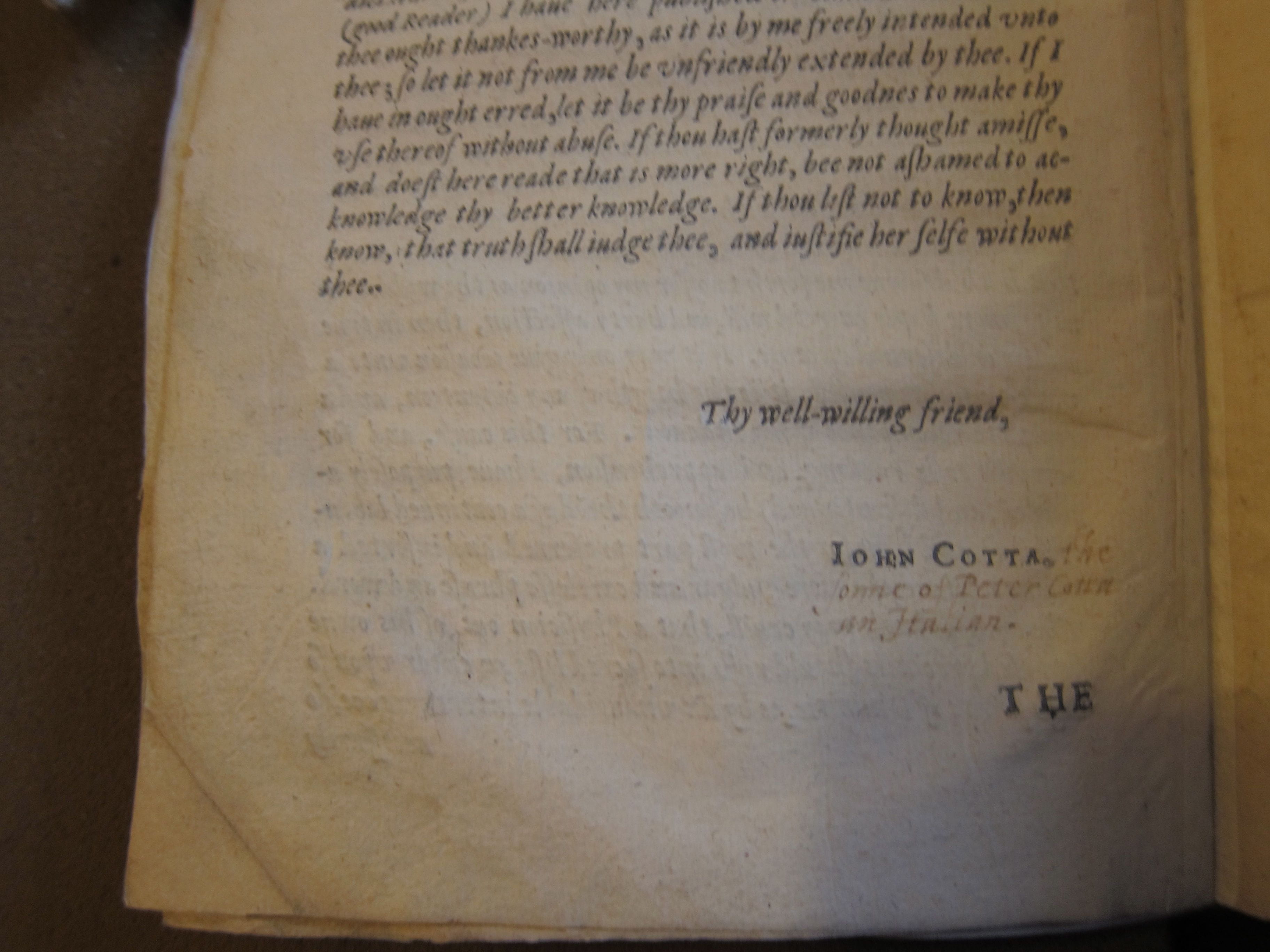

Here, where Cotta signed his preface “John Cotta,” Adam added that he was “the sonne of Peter Cotta an Italian”:

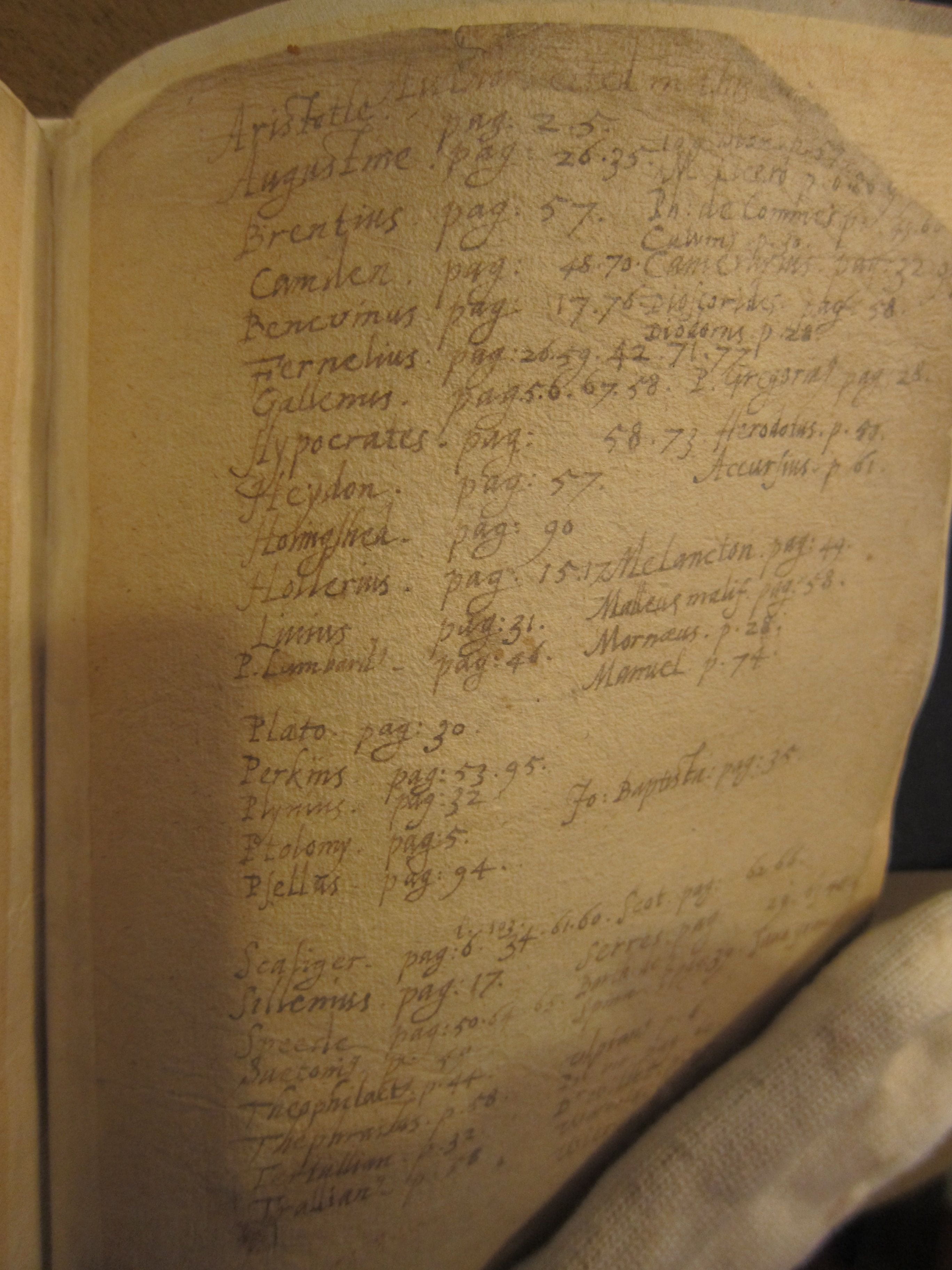

And in the back of the book, Adam constructed a remarkably detailed index of “authors cited” in the treatise. He listed diverse sources ranging from ancients like Plato, Aristotle, and Augustine to moderns like Scaliger, and Melanchthon, and supplied the page numbers where his nephew had mentioned them:

Adam’s meticulous annotating not only identified and recorded the conversations his books had had with one another, but also fixed their authors in time, space, and circumstance. Annotation was a tool that rendered a motley assortment of books into a single unified library. As I’ll discuss in the next installment, it was also a tool that made a library mobile and expandable—as Adam’s grandson John Jr. used the very same methods of annotation when transporting this library across the Atlantic, and expanding its contents still further.

Frederic Clark received his PhD from Princeton in 2014 and is currently a Mellon postdoctoral fellow at Stanford. His research focuses on the cultural and intellectual history of early modern Europe, especially book history, classical reception, and the history of historical thought. He, Erin McGuirl, and JHI Blog editor Madeline McMahon are the curators of Readers Make Their Mark: Annotated Books at the New York Society Library (through to August 15, 2015).

February 9, 2015 at 7:58 pm

Reblogged this on the surface of things and commented:

I’ve never re-blogged anything in this space, but this post on book annotations and marginalia from the JHI blog is worth it. Especially since John Winthrop’s “Model of Christian Charity” is on my desk, in preparation for class this week!

November 15, 2015 at 5:34 pm

Reblogged this on The Winthrop Project.