by guest contributor Sarah Dunstan

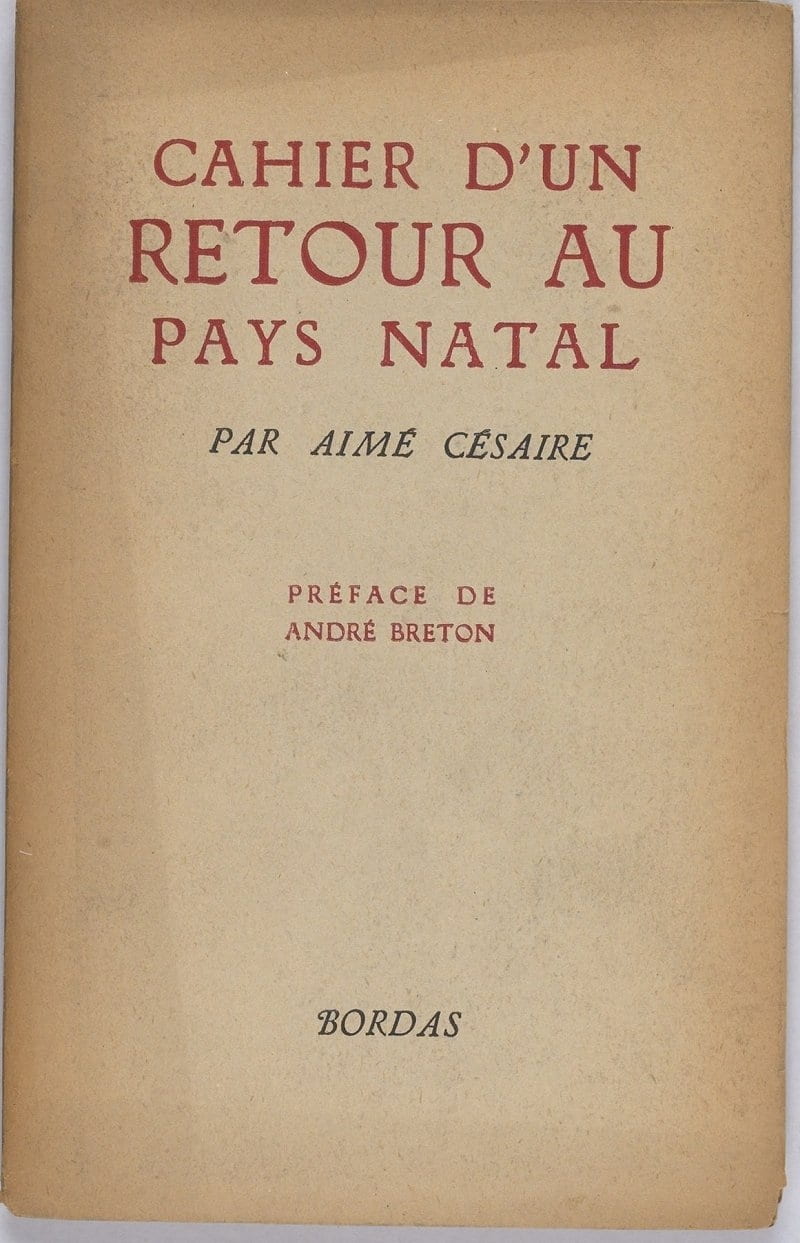

With the publication of his famous Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (English trans.) in 1937, Aimé Césaire introduced the word Négritude into the French lexicon. In so doing, he named the black literary and cultural movement that he, along with the Senegalese politician and poet Léopold Senghor and Guinian poet Léon Damas would employ to critique colonial practice and construct a powerful new black identity. As T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting argues, the origins of the neologism Négritude may be easily traced to Césaire but its role in the history of black intellectual thought remains controversial, not least because it straddles the boundaries of a linguistic divide and rests upon a decidedly masculine etymology.

Study of the so-called trois pères of Négritude—Senghor, Césaire and Damas—has long framed histories of the movement, with their personal relationships and political trajectories offering insight into the content of their thinking. Particular emphasis has been placed upon their use of the French language and their French education. More recently, scholars have pushed back the temporal and linguistic boundaries of the movement’s periodization, rooting its origins in the early 1920s and recognising the Anglophone influence of the work of African American writers. This is due partly to acknowledgements by Césaire and Senghor of their engagement with the work of the Harlem Renaissance. Writers such as Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen were introduced to francophone audiences as early as 1924 in the short-lived journal Les Continents. Post-World War 1 dialogue between African American and Francophone black thinkers, however, went back to the 1919 Pan-African Congress organised by Du Bois wherein men such as the Senegalese politician Blaise Diagne and Guadeloupian politician Gratien Candace conceptualised black political and cultural identity upon firmly national lines.

The issue of Négritude’s intellectual debts and legacy is not purely linguistic and national, however, but entangled with questions of gender. As scholars such as Sharpley-Whiting, Brent Hayes Edwards and Jennifer Anne Boittin have noted (and gone far to rectify), the role played by black women in crafting and catalysing the movement has long been under-studied. Antillean sisters Paulette and Jane Nardal, for example, exercised a strong influence both in intellectual and practical terms, holding salon-style meetings in Paris in the late 1920s and early 1930s. These meetings brought together luminaries from both the Anglophone and Francophone black diaspora to discuss the questions of identity that underpinned many of the works associated with Négritude. The Nardal’s salons are famed for producing La Revue du monde noir, a bilingual journal that ran for six editions and had a distinctly internationalist bent. Most scholars of the black francophonie would now acknowledge the Nardals and the Revue as crucial influences upon the intellectual development of les trois pères. The initial elision of the women from narratives about the movement is one, however, that also bears true of intellectual histories of African diasporan exchange during this period.

The availability of sources is part of the problem as scant archival material exists outside their published work. Correspondence like that so crucial to tracing the exchange between African American thinkers such as Alain Locke and René Maran is largely missing from the historical archive where these black women are concerned. A 1956 fire destroyed Paulette Nardal’s papers, for example, making her role in the origins of the Négritude movement and as a generator of diasporan intellectual exchange even more difficult to map. What is left are the articles she published in La Dépêche africaine and La Revue du Monde Noir and a patchwork of police surveillance records in the ‘Service de liaison avec les originaires des territoires français ďoutre-mer’ series held in the overseas archives in Aix-en-Provence.

On the American side, women such as Jessie Fauset and Ida Gibbs Hunt have no archives to their name. Nevertheless, their correspondence shows up in the papers of their friends and acquaintances – men such as Langston Hughes, W.E.B. Du Bois, Gratien Candace and Rayford Logan. This affords tantalising glimpses of the crucial, if mostly unacknowledged, parts they played in facilitating intellectual exchange across the language divide. Ida Gibbs Hunt, for example, was part of the first Pan-African Association executive committee formed in 1919 at the Pan-African Congress in Paris. Du Bois never mentioned her in his write-up of the Congress in the Crisis, nor does she appear in any media reports. Yet a personal letter that Du Bois sent to Hunt and her husband (the American consul to Saint-Étienne at the time) suggests that she was, in fact, heavily involved in its organisation. In addition, correspondence appearing in the Du Bois Papers held at the University of Massachussets-Amherst suggests that Hunt, alongside Rayford W. Logan, played a mediating role in maintaining fragile diasporan relations when Du Bois consistently infuriated and circumvented the francophone portion of the organising committee.

Historian Glenda Sluga, in a roundtable at the History Workshop, noted similar archival silences in regard to the presence of female actors in internationalist movements. It prompted her to ask if their inclusion should be “a matter of choice, or a matter of fact?” I think the answer lies in innovation, in being open to intellectual genealogies that go beyond the traditional or, in the case of les trois pères, the acknowledged narrative. In a brilliant article, on the Nardal sisters in interwar Paris, Jennifer Anne Boittin illustrated one way in which such miscellaneous sources can be patched together to form a broader picture. Amongst other findings, Boittin’s work illustrated the ways that women like the Nardals often formed intellectual coalitions upon gendered lines, sharing space in journals such as La Dépêche africaine with white feminist thinkers such as Marguerite Martin. Choosing to interrogate the gaps and silences often left in intellectual genealogies by female actors can allow us to see these connections and thus view cultural and political movements like Négritude and Du Bois’ Pan-Africanism in a new light, fleshing out their spheres of influence beyond the expected.

Sarah Dunstan is a PhD Candidate on an Australian Postgraduate Award at the University of Sydney. For the 2014-2015 academic year, she is based at Columbia University, New York, on a Fulbright Postgraduate Fellowship. Her research focuses on francophone and African American intellectual collaborations over ideas of rights and citizenship.

March 7, 2015 at 5:20 pm

Thanks for this great post, Sarah! My research struggles also with how to get at women’s participation in intellectual/academic culture through largely male-created archives. This article by Judith Walkowitz has been a jumping-off point for how I think about some of this: http://hwj.oxfordjournals.org/content/21/1/37.full.pdf – though its approach is perhaps due for an update from a new generation of historians!

March 9, 2015 at 6:56 pm

Thanks for your feedback Emily! I will have a look at Judith Walkowitz’s article!

March 7, 2015 at 6:17 pm

This is a wonderful reflection, Sarah! I have one very basic question to ask. Historically, women often play a hidden if key role as translators, editors, and publishers in avant-garde literary movements. I’m curious as to whether and, if so, how people like Fauset helped Césaire and his colleagues find an audience in America. (Perhaps there might be some archival traces left in publishers’ holdings if so ….) It seems to me that their politics would have been received in all sorts of strange ways in America or, perhaps, not at all: they could have been purposely or inadvertently presented as purely literary figures. But I’m also learning just now how quickly and strongly anti-colonial feelings were springing up in interwar America. So, is there a story to be told about Négritude in America as well as vice-versa, as you’ve so elegantly suggested?

March 9, 2015 at 7:17 pm

Thank you John. That is a really great question! Interestingly enough, Jessie Fauset used to translate much of Du Bois’ correspondence with people such as Blaise Diagne & Gratien Candace. Clara Shepherd, an African American lady who worked with the Nardal sisters on the Revue was also responsible for many of the translations that appeared in that publication.

There is most certainly a story to be told about Négritude in America as well as vice-versa and much of my dissertation will focus on just those exchanges.The way that some of the works were translated often profoundly shaped the reception they had. A case in point in the translation of Claude McKay’s ‘Banjo’. The French translation utilised a decidedly Communist vocabulary that had been missing from the English original. Some of the key figures I study also devoted their time to translating texts. Langston Hughes, for example, is best known for his poetry and political commentary but he was responsible for introducing many francophone and Spanish writers and thinkers to American audiences.

March 8, 2015 at 2:49 pm

Early modernists have attacked these issues too for the last generation, from the classic article by Deborah Harkness, “Managing an Experimental Household: The Dees of Mortlake and the Practice of Natural Philosophy,” Isis, Vol. 88, No. 2, 1997, pp.247 -262 to some amazing recent books like Sarah Ross, The birth of feminism: woman as intellect in Renaissance Italy and England (Harvard, 2009) and Carol Pal, Republic of women: rethinking the Republic of Letters in the seventeenth century (Cambridge, 2012)–not even to mention the copious literature on the salons of Paris.

March 9, 2015 at 7:18 pm

That’s really interesting to know! I am familiar with Deborah Harkness’ wonderful article but I shall certainly have to look at Sarah Ross and Carol Pal’s work. Thank you for the recommendations!

January 7, 2020 at 12:36 pm

Do also check out Suzanne Césaire: the Unknown Mother of Antillanité, because she was a founding writer of the magazine Tropiques, dissented with her husband, and was author of the 7 essays (The Great Camouflage: Writings of Dissent 1941-47). Her writings clearly inspired Edouard Glissant’s thinking…

Once again, as Virginia Woolf stated:” For most of history, Anonymus was a woman .;;”