by guest contributor Erin McGuirl

In the spring of 1989, Mai-mai Sze (1909-1992) and her partner Irene Sharaff (1910-1993) were looking for a home for their library. The collection is strong in East Asian religion, philosophy, and scientific history and well-stocked with classics in translation, English literature, books on art, and western philosophy from ancient to modern. After rejections from Wellesley College, Sze’s alma mater, and Yale, where the School of Drama Library had taken a portion of Irene’s drawings and designs, the couple looked elsewhere. Through a connection at the Cosmopolitan Club, the books came to the New York Society Library, a subscription library founded in 1754 and the oldest library of any kind in New York City. All biases aside (I’m the Special Collections Librarian there), it’s a good fit. Founded as a secular alternative to the Anglican King’s College Library, the Society Library has always operated outside of the academy or perhaps as an autodidact’s alternative toit. As the scholarly character of their heavily annotated library suggests, the Sharaff/Sze Collection is a living record of two creative, educated women who maintained an intense and active engagement in scholarly culture throughout their lives. Today, their books show how these two artist-intellectuals engaged with literary and scholastic culture in New York City in the twentieth century, and carried on a long established tradition of engaged reading that extends far beyond the library.

Irene Sharaff is not nearly so present in the collection as Mai-mai Sze. Best remembered for her translation of the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting (Bollingen Foundation, 1956), Sze never established a career as a scholar or translator, but she read like one. Her annotations in books like Joseph Needham’s Science and Civilisation in China (the subject of my follow-up post) are full of cross-references and translations, and she often wrote her own indexes. In addition to her notes, Sze’s books preserve a biblio-geographical breadcrumb trail connected to a global community of intellectual readers.

![Mai-mai Sze’s copy of John Donne: Complete Poetry and Selected Prose. London: The Nonesuch Press, 1932. Clipping laid in at rear cover. Smith, A. J. "A John Donne Poem in Holograph." Times Literary Supplement [London, England] 7 Jan. 1972: 19. Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive. Web. 16 Apr. 2015.](https://jhiblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/fig1_donne-and-mai-mai1.jpg)

Mai-mai Sze’s copy of John Donne: Complete Poetry and Selected Prose. London: The Nonesuch Press, 1932.

![Clipping laid in at rear cover. Smith, A. J. "A John Donne Poem in Holograph." Times Literary Supplement [London, England] 7 Jan. 1972: 19. Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive. Web. 16 Apr. 2015.](https://jhiblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/fig1_donne-tls-clipping.jpg)

Clipping laid in at rear cover. Smith, A. J. “A John Donne Poem in Holograph.” Times Literary Supplement [London, England] 7 Jan. 1972: 19. Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive. Web. 16 Apr. 2015.

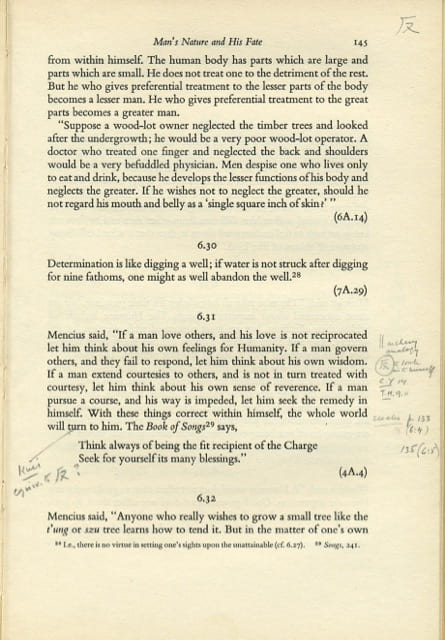

Mencius. Mencius: a new translation arranged and annotated for the general reader. London: Oxford University Press, 1963, with annotations by Mai-mai Sze. Sharaff/Sze Collection, New York Society Library

Mencius. Mencius: a new translation arranged and annotated for the general reader. London: Oxford University Press, 1963, with annotations by Mai-mai Sze. Sharaff/Sze Collection, New York Society Library

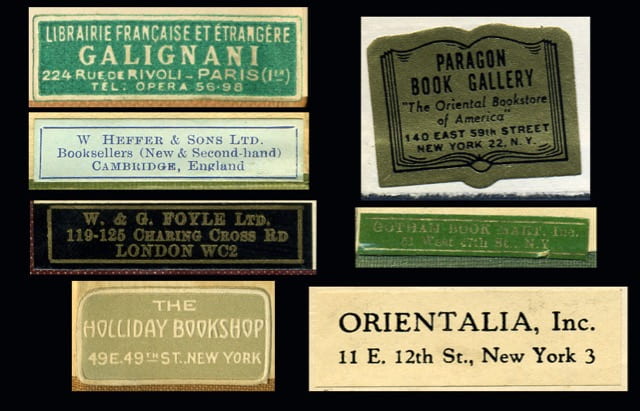

Booksellers’s labels also connected Sze with an international community of scholarly-minded readers in more direct and personal ways. In New York, she visited the Holliday Bookshop, Gotham Book Mart, The Paragon Book Gallery, Books & Co., Orientalia, and Museum Books. In Europe, we find her at Heffer’s in Cambridge, Blackwell’s and Parker’s in Oxford, W. & G. Foyle and the Times Book Club in London, and Galignani’s in Paris. Shops like these catered to educated readers, many of whom were also active members of academic, literary, dramatic, and artistic circles. The Gotham Book Mart and Books & Co. are particularly well known for the social, literary-artistic scenes they fostered, and the others pop up (like Sze herself) in the memoirs of New York writers and artists who worked, shopped, and socialized there.

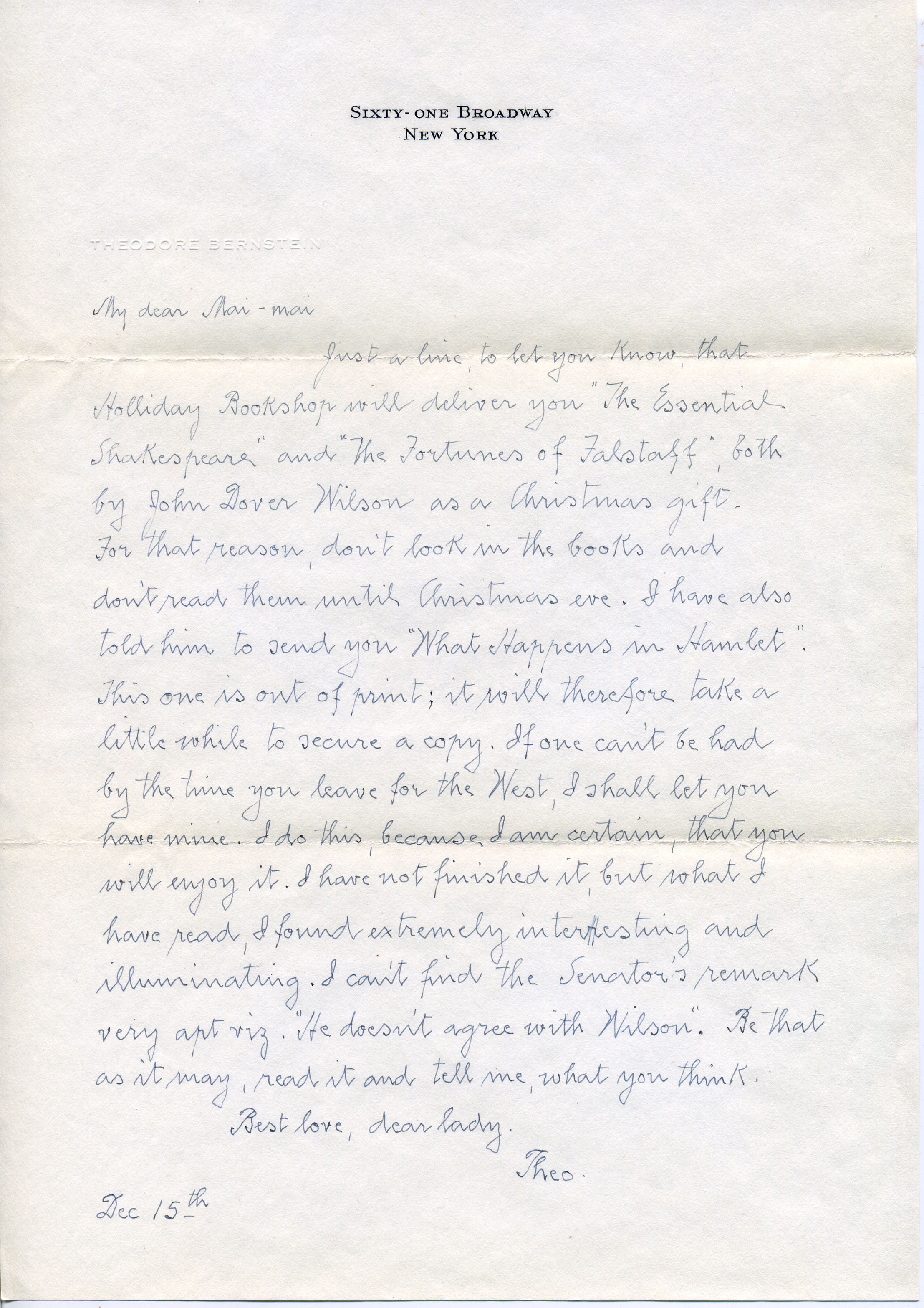

Few of Sze’s letters survive, and the best are in bookshop archives. In the 1950s, she corresponded with bookseller and sometime literary critic Terence Holliday. The muted-gray label of the Holliday Bookshop appears more often than any other in the Sharaff/Sze Collection. The 49th Street bookstore was founded in 1920 by Terence and Elsa Holliday, and specialized in English imports. The Hollidays drafted a memoir of the life at the shop (printed in The Book Collector, volume 61, issues 3-4), and they wrote that they decided to “stick strictly to the selling of books. There were to be no side lines, no gifts, no tea serving, no authors’ parties. And we would never have a shop on the street level.” This was a shop for readers who wanted their booksellers to know how to find out of print and specialized publications. It was for people who read a lot, who read reviews, who called the shop and placed orders for themselves and for their friends. This letter from Theodore Bernstein to Mai-mai (c. 1944) shows that he called the bookshop to have three titles on Shakespeare by John Dover Wilson sent to her as a Christmas gift.

Theodore Bernstein to Mai-mai Sze, 15 Dec. 1944? Sharaff/Sze Collection File, Institutional Archives, New York Society Library (click for larger view)

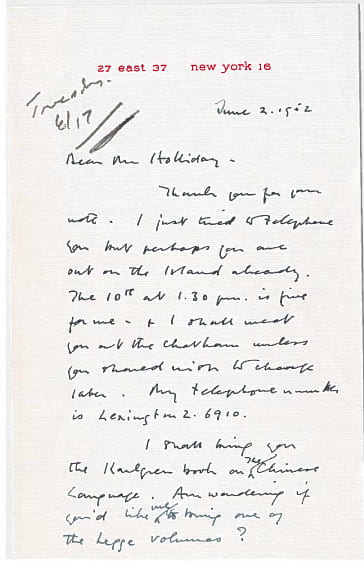

Sze wrote Mr. Holliday in 1943, when she lived just 12 blocks from the shop on 37th street to thank him for yet another gift. Eleven years later she wrote again to set a date for an informal “seminar,” saying that she would bring her copy of “Karlgren’s book on the Chinese language,” which is annotated and part of the Sharaff/Sze Collection today.

Mai-mai Sze to Terrence Holliday, 2 June 1952. Holliday Bookshop Collection, Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College (click for larger view)

Mai-mai Sze to Terrence Holliday, 2 June 1952. Holliday Bookshop Collection, Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College (click for larger view)

Collections like Mai-mai Sze’s vividly show us just how actively cosmopolitan intellectuals developed their minds, in both public and private spheres. In many ways, her reading extends the kind of knowledge-gathering we see in early moderns like the Winthrops, a familial network of readers who relentlessly cultivated their minds across continents and generations. In Mai-mai Sze’s library we see how the tireless reader thoughtfully picking her own path through the vast territory of human knowledge—on a global scale, from the distant past to the present—traversed the twentieth century.

Erin McGuirl is the Special Collections Librarian at the New York Society Library. You can see Mai-mai Sze’s annotated books there at Readers Make Their Mark: Annotated Books (through to August 15, 2015).

April 20, 2015 at 11:51 pm

What a wonderful trail to follow! And what a different vision of New York intellectual life it offers: for once, it’s not a story about Jewish men and little magazines.

April 21, 2015 at 8:35 am

Thanks so much, Tony! I can’t wait to see what turns up when I really get digging into her notes on Needham. I keep hoping that letters between those two will surface somewhere.

April 21, 2015 at 3:21 pm

I also loved the Bollingen materials you turned up so brilliantly in LC. It’s inspiring to see how that great collection was put together, print order by print order.