by guest contributor Elizabeth Ott

Debates about the proper function of public libraries—what readers they should serve, what kinds of reading they should promote, what sorts of books should stock their shelves and (perhaps most importantly) how those books and shelves should be paid for—have dogged discussions of public libraries since their first inception. These debates have never been politically neutral, yet they have been particularly charged in recent years, as conservative economic policies have forced the closure of many libraries around the United Kingdom. In this climate, libraries, librarians, and library users are charged to articulate what value public libraries offer to offset the cost of their operation.

Often these articulations rely upon the rhetoric of moral improvement: reading becomes synonymous with education, a safe activity that guards against the dubious pleasures of modernity. The library itself is cited as a place of community-building, a neutral space of wholesome civic engagement. These lines of argument have the effect of casting public libraries in relation to a sense of time: either libraries are preserving a sense of the past, a golden moment in history when reading (usually figured as inherently superior to, say, television, the internet, etc.) was ubiquitous, or libraries are a gateway to progress, an investment in national advancement.

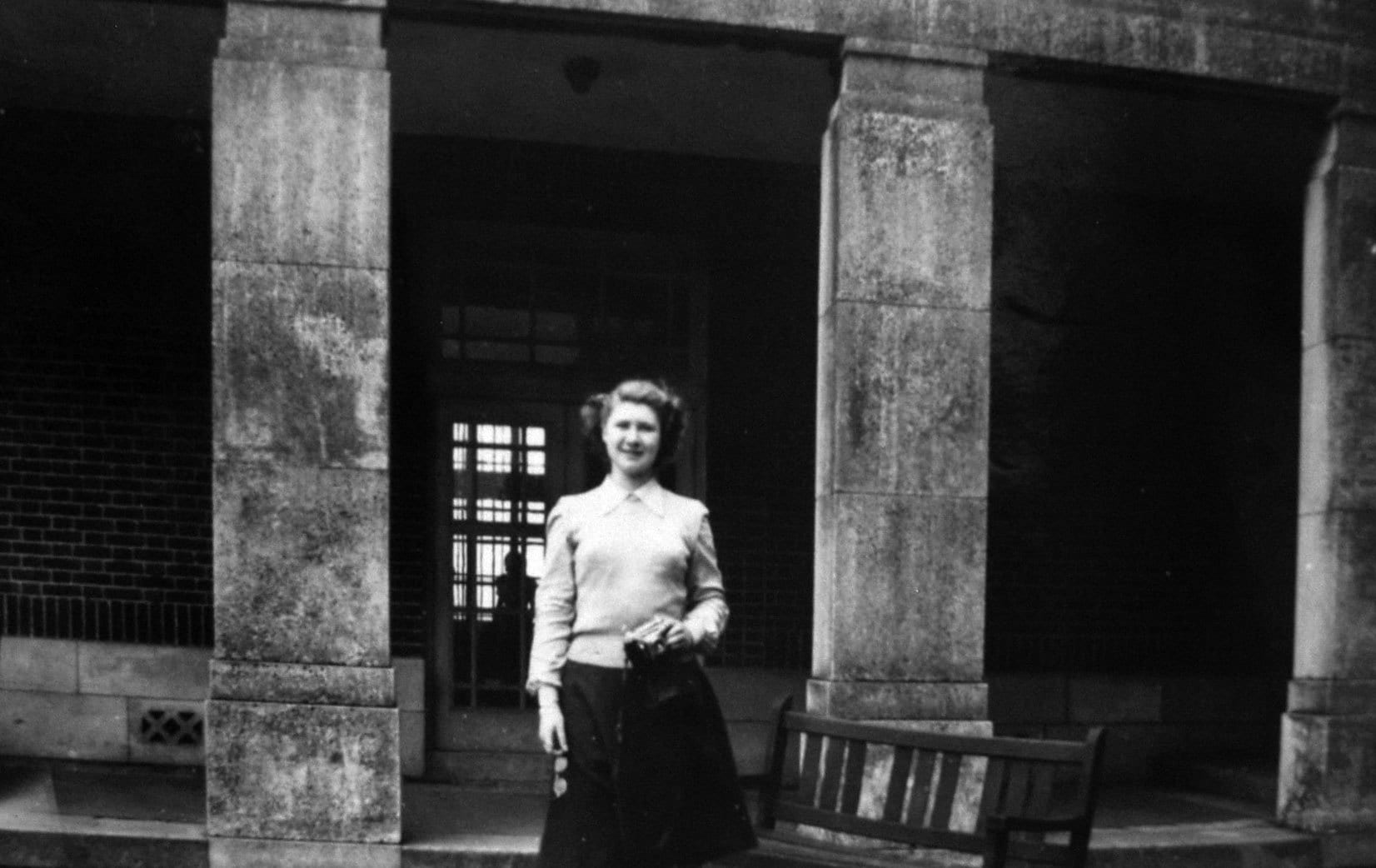

Jean Wolfendale, Sheffield Reader

The tension between these two modes of articulating value in public libraries can be seen in a recent interview in the Guardian with writer Neil Gaiman. Gaiman’s interlocutor, Toby Litt, asks a series of leading questions, such as this one: “Isn’t the future of libraries dependent on not having gatekeepers who are scary, on libraries not looking ancient, and not being about distant, old knowledge?” This question is loaded with valuations of what is good (progress, youth, the future) and what is bad (history, age, the past). It is impossible to read it without jumping to a conclusion about the kind of library he is indicating: the scary gate-keeping crone who guards ancient tomes in a derelict Carnegie building whose sagging walls speak of years of civic neglect. Gaiman is largely uninterested in engaging this discourse, and instead uses the space of the interview to explore his own personal and imaginative interaction with libraries as a young reader. Nevertheless, his metaphor of the library as “seed-corn” which ends up titling the article, contributes to a progress narrative.

In this context, the Reading Sheffield project is delightfully radical. Though in many ways the project tropes the library as a preserver of history (the main page of the website invites readers to “be transported to Sheffield’s past. To a time without Google or Apple, a time when the world went to war and then re-built itself, a time when most children left school at 14 and most women did not work outside the home”), it significantly places no value whatsoever on reading as an improving activity, instead championing reading as an activity of leisure. Against the backdrop of a largely working class readership, Reading Sheffield is “a resource for anybody seeking to explore, celebrate, or promote reading for pleasure.”

At the core of the Reading Sheffield project is series of sixty-two interviews with residents who lived in Sheffield, England during the 1940s and 1950s, conducted over a two-year period by twelve trained volunteers. These oral histories of reading are fully transcribed and available on the website, along with embedded audio files. Interview subjects recollect how they accessed the library, when they first became readers, what they read, and how their reading intersected with their daily lives. These recordings have significant historical value as a record of reader activity—an aspect of reading history that’s especially fleeting and difficult to capture—and as markers of social history. In recounting their memories of library use, each interviewee also records detailed information about the culture of post-war Britain in which they read. Archival quality audio recordings of the interviews have been deposited with the Sheffield Archives and Sheffield Hallam University, in addition to being made available online.

One Sheffield reader mentions trips to the Hillsborough Library, which hosted a reading club group for young people on Wednesday evenings.

Because of the average age of interview participants, the Reading Sheffield oral histories recall the privation of post-war England in the 1940s and 1950s. Readers reference the scarcity of paper, shortages of food, the sheer difficulty of visiting library branches when tram rides proved too expensive and a trip across town meant an arduous trek in both directions. The interview format prompts recollections along a defined pathway: when did you first learn to read? What were your first books? Which library branches did you visit and how did you get there? What books did you own and what books did you borrow? This last question is one that particularly highlights the library’s function as a place of pleasure reading, as often interviewees make a distinction between the kind of practical books purchased for the home (bibles, trade manuals, school books) and the books vividly recalled from library visits: “Well the books from the library I think were all novels.”

Beyond its function as a repository of oral history, the project seeks to imaginatively engage with readers’ histories in a variety of ways—most interestingly through its Readers’ Journeys: “interpretive articles based on our readers’ interviews,” written by project team members, that may “not necessarily represent the views of the interviewees.” These articles attempt to match oral histories with the places and spaces they recollect, drawing out tangential narratives that emphasize the importance of libraries and library buildings in the social life of the community.

Sheffield, like many cities in the United Kingdom, has weathered threats of library closure. It was the site of community protests in 2014 over the planned closure of approximately 16 branch locations; these closures were only avoided through the use of volunteer labor, replacing professional and staff positions at many branches. Reading Sheffield, too, is built on the labor largely of volunteers, whose efforts to preserve community history in the face of erasure are commendable, as is their message that readers deserve a community space for shared pleasure, outside any system of utilitarian value.

Elizabeth Ott is Assistant Curator of Rare Books at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Libraries. Her doctoral work is on the history of subscription and circulating libraries in England.

1 Pingback