By guest contributor Udi Greenberg

This post is a companion piece to Prof. Greenberg’s article in the most recent issue of the Journal of the History of Ideas, “Catholics, Protestants, and the Tortured Path to Religious Liberty.”

A series of recent controversies in Europe and the United States have sparked intense interest in the scope and limits of religious liberty. Can governments make sure everyone has the right to freely practice their faith? Should they protect this right even if it clashes with other priorities and principles, such as national security imperatives or anti-discrimination statutes? While almost all the participants in these debates—politicians, jurists, commentators, and social thinkers—claim to be defenders of religious freedom, they assign profoundly different meanings, goals, and consequences to this term. Progressives have invoked it to decry anti-Muslim measures such as anti-veil laws in Europe or the “Muslim ban” in the United States, while conservatives have used religious liberty to defend the right to discriminate against single-sex couples, deny access to birth control, and ban displays of certain religious faiths. Perhaps because it is so heavily contested, the language of religious liberty has acquired a significant aura in contemporary public, political, and legal discourse. Like “democracy,” “justice,” and “freedom,” it is a term that radically different camps seek to claim as their own.

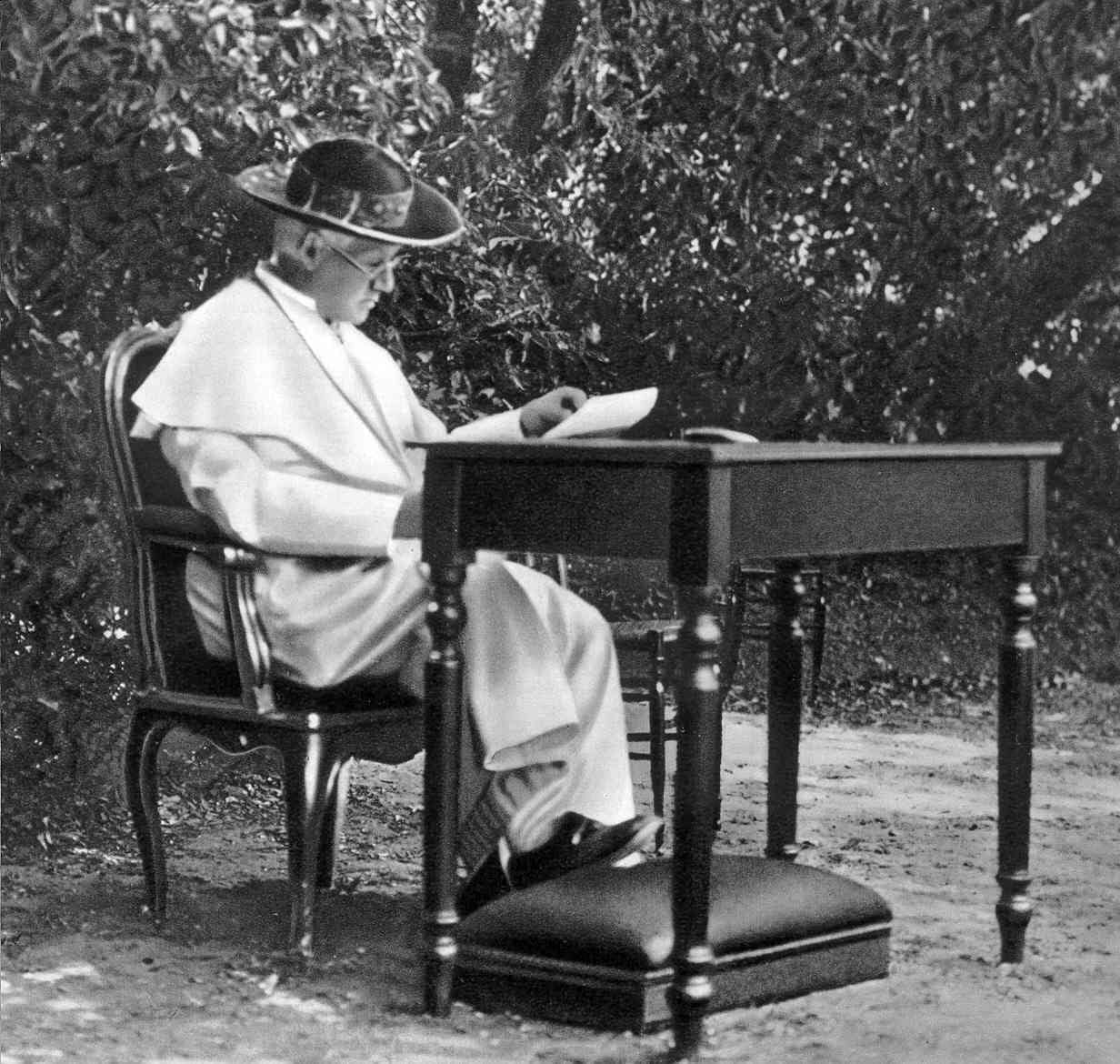

Pope Gregory XVI

It can therefore be surprising to remember how recent religious liberty’s popularity is. Few institutions reflect this better than the Catholic Church, which as recently as the early 1960s openly condemned religious freedom as heresy. Throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, Catholic bishops and theologians claimed that the state was God’s “secular arm.” The governments of Catholic-majority countries therefore had the duty to privilege Catholic preaching, education, and rituals, even if they blatantly discriminated against minorities (where Catholic were minority, they could tolerate religious freedom as a temporary arrangement). As Pope Gregory XVI put it in his 1832 encyclical Mirari vos, state law had to restrict preaching by non-Catholics, for “is there any sane man who would say poison ought to be distributed, sold publicly, stored, and even drunk because some antidote is available?” It was only in 1965, during the Second Vatican Council, that the Church formally abandoned this conviction. In its Declaration on Religious Freedom, it formally proclaimed religious liberty as a universal right “greatly in accord with truth and justice.” This was one of the greatest intellectual transformations of modern religious thought.

Why did this change come about? Scholars have provided illuminating explanations over the last few years. Some have attributed it to the mid-century influence of the American constitutional tradition of state neutrality in religious affairs. Others claimed it was part of the Church’s confrontation with totalitarianism, especially Communism, which led Catholics to view the state as a menacing threat rather than ally and protector. My article in the July 2018 issue of the Journal of the History of Ideas uncovers another crucial context that pushed Catholics in this new direction. Religious liberty, it shows, was also fueled by a dramatic change in Catholic thinking about Protestants, namely a shift from centuries of hostility to cooperation and even a warm embrace. Well into the modern era, many Catholic writers continued to condemn Luther and is heirs, blaming them for the erosion of tradition, nihilism, and anarchy. But during the mid-twentieth century, Catholics swiftly abandoned this animosity, and came to see Protestants as brothers in a mutual fight against “anti-Christian” forces, such as Communism, Islam, and liberalism. French Theologian Yves Congar argued in 1937 that the Church transcends its “visible borders” and includes all those who have been baptized, while German historian Joseph Lortz published in 1938 sympathetic historical tomes that depicted Martin Luther and the Reformation as well-meaning Christians. This process of forging inter-Christian peace—which became known as ecumenism—reached its pinnacle in the postwar era. In 1964, it received formal doctrinal approval when Vatican II promulgated a Decree on Ecumenism (1964), which declared Protestants as “brethren.”

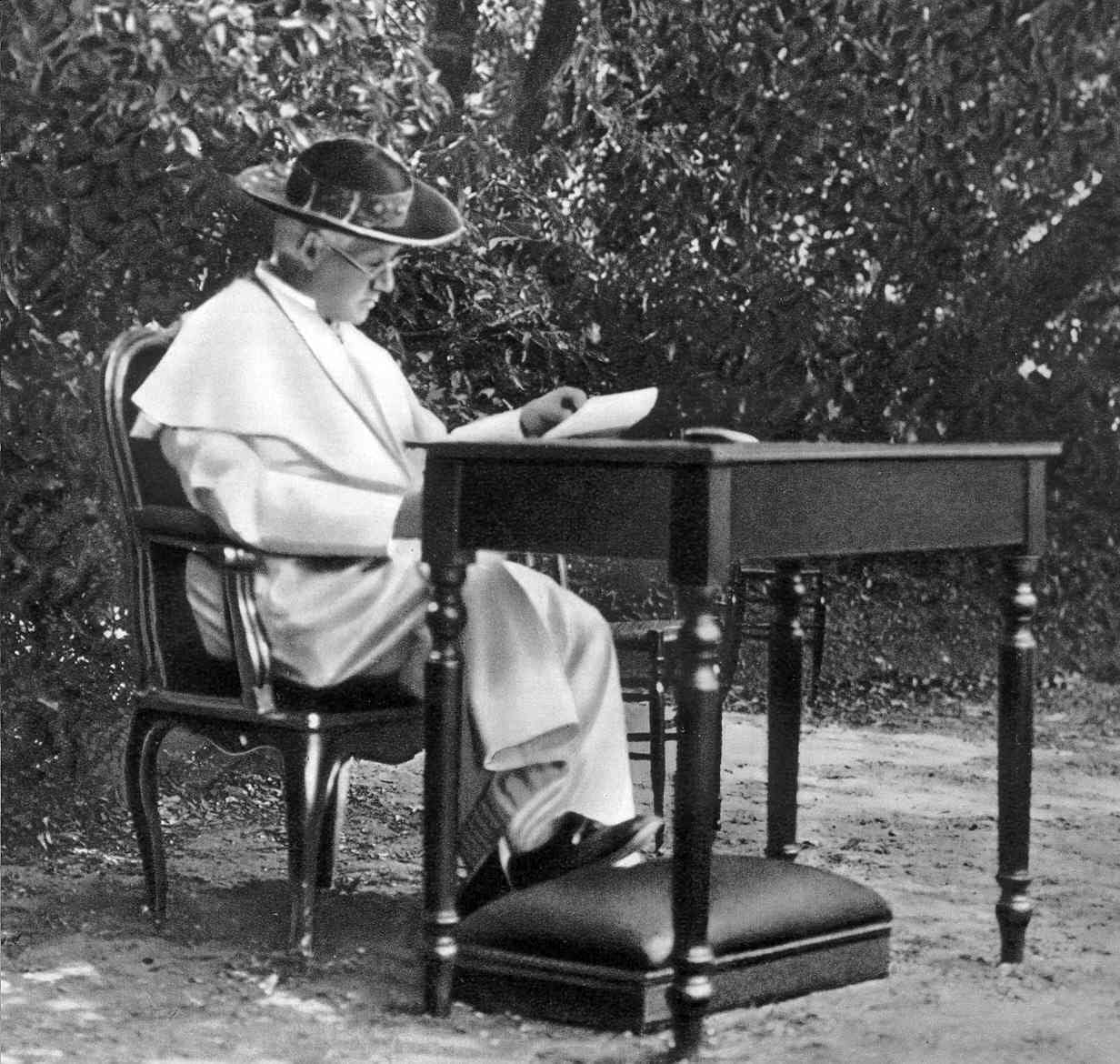

Pope Pius X

It was in this context that Catholic leaders also shed their opposition to religious liberty. Catholic thinkers had long demonized religious liberty as a Protestant conspiracy that allowed Luther’s heresy to thrive. This was the spirit in which Pope Pius X, in his famous 1910 encyclical Editae saepe, decried Protestants for “pav[ing] the way for modern rebellions and apostasy.” But after the Church embarked on its quest for cooperation with Protestants, it also reconsidered its approach to state institutions. They no longer required Catholic countries to impose Catholic education and practices. Indeed, for many Catholic writers, interdenominational peace required a new approach to the state, where no church held formal legal hegemony; they believed that the two intellectual projects—making peace with Protestants and revising Catholic teachings on the use of state power—were ultimately inseparable. It was no coincidence that the thinkers who drafted Vatican II’s Declaration on Religious Freedom also penned the Decree on Ecumenism. Both texts also emerged from the same organ, the Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity.

This story may seem like a scholastic dive into arcane theological debates, but it has broader implications for our own debates about religion and politics. It raises questions about the origins of contemporary laws that regulate religion in Europe and the United States. Reflecting on recent controversies, some scholars have often attributed religious liberty laws to the ideology of “secularism” (or laïcité in French). If countries like France, they have asserted, routinely discriminate against Muslims through actions like banning the veil, it is in part (though not exclusively) because of an obsession with secular public affairs cannot digest certain religious behaviors or open displays of faith. Yet as this story of Catholic thinking reveals, religious liberty is not simply the product of secularist ideas. In some cases, it was the product of inter-confessional peace between Catholics and Protestants, whose architects had no aspirations of promoting universal religious equality. On the ideological level, ecumenical religious freedom in fact sought to maintain religious dominance in the public sphere by joining forces against “anti-Christian” enemies. It thus may be that religious liberty is best understood not only as the product of secular ideas and conditions. Rather, it was also the work of religious actors and ideas—a legacy that continues to profoundly shape contemporary political and public life.

Udi Greenberg is an associate professor of European history at Dartmouth College. He is currently writing a book titled Religious Pluralism in the Age of Violence: Catholics and Protestants from Animosity to Peace, 1879–1970. Together with Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins, he edited a special forum on Christianity and human rights in the latest issue of the Journal of the History of Ideas; the introduction to that forum can be found here.

Leave a Reply