by Madeline McMahon

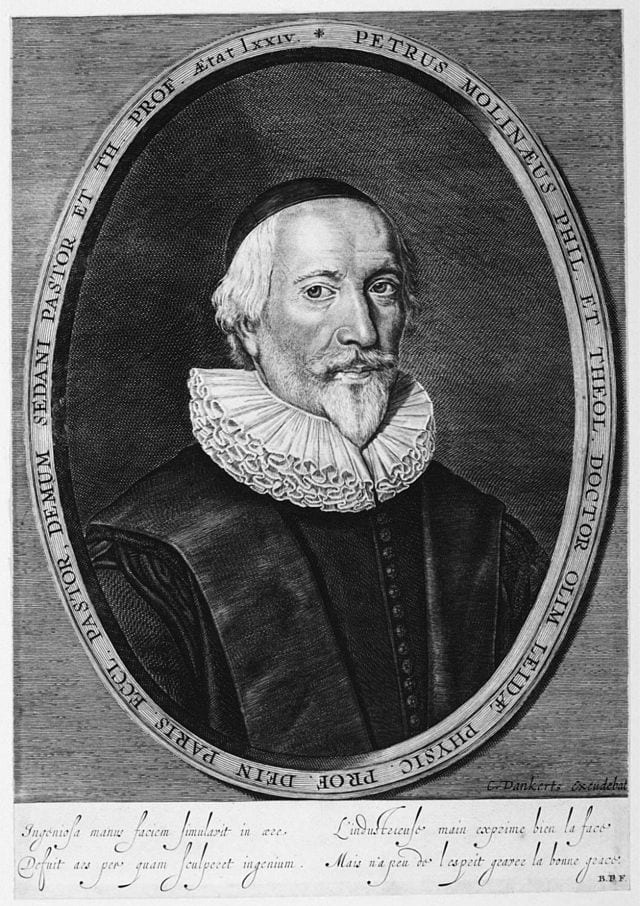

Pierre Du Moulin (1568 – 1658) was, paradoxically, an irenic and ecumenical controversialist. As a prominent minister in the French reformed church, Du Moulin wrote almost one hundred polemical pamphlets and books against Protestants and Catholics alike (W. B. Patterson, “Pierre Du Moulin’s Quest for Protestant Unity,” 236). Yet from 1613 to 1618, he devoted much of his energy to planning the union of the reformed churches. Under the influence of the British king, James VI and I, he reconciled himself to one of his Protestant opponents. He did not abandon his polemical stance: in fact he defended the king’s own controversial works against the Catholic writer Robert Bellarmine (Patterson, ibid.). Du Moulin worked his way into the royal favor, knowing that the supreme head of the Church in England would be crucial to his plans for Christian unity. In 1615, Du Moulin traveled to England, where he was awarded degrees at Cambridge and given a stipend (prebend) in the English Church.

But, although united in their scheme to unify the Protestant churches, James and Du Moulin did not always agree. Once Du Moulin had returned to France, he resumed his controversial writings. In 1618, he published two works against a Jesuit court preacher: Le bouclier de la foi and De la vocation des pasteurs. Le bouclier contained the essence of the French Protestants’ beliefs, upheld against the attacks made by the Jesuit Arnoux. It appealed to an English audience and was translated in 1620, with a preface dedicated to the prince of Wales by Du Moulin himself. Yet the English king found Du Moulin’s work on pastors more troublesome and less translatable into an English context due to its treatment of bishops.

James’ disapproval of his book led Du Moulin to reach out to an English bishop. He got in touch with one of the king’s favorites, whom he had met when he visited England: Lancelot Andrewes, newly consecrated bishop of Winchester. “I send [my book De la vocation des pasteurs], because, since you enjoy a more frequent and nearer presence of His Majestie, I doubt not but He may have some speech with you about it, and use you as an umpire in the cause,” he wrote in September of 1618 (Of Episcopacy (1647), 6. NB: for convenience, I am citing the English translation from 1647; the original Latin text can be found in the 1629 publication or in the nineteenth-century edition of Andrewes’ works). Andrewes, however, didn’t get back to the French cleric right away. A few months later, Du Moulin wrote him once more, sending him a different book (probably Le bouclier de la foi) and again entreating him: “I desire that you would be a means to pacifie the Kings anger against me” (21).

When he finally replied, Andrewes was less understanding than Du Moulin had hoped. Andrewes and Du Moulin could not see eye to eye about episcopacy and the role that bishops should play versus that of presbyters. Du Moulin repeatedly assured his correspondent that he was not adverse to bishops like the presbyterians and puritans Andrewes knew in an English context. (In fact, only five years later, Du Moulin would try to obtain the bishopric of Gloucester!) Andrewes, however, made a hard case that episcopacy stemmed from apostolic times and was therefore established in divine law (16). The English Church thus had not only the best but also the only acceptable form of church governance: “no form of Government in any Church whatsoever cometh neerer the sense of scripture, or the manner and usage of the Antient Church, then this which flourisheth among us” (18). Andrewes assured Du Moulin that he did not consequently damn the French reformed church:

though Our Government be by Divine Right, it follows not, either that there is no salvation, or that a Church cannot stand, without it. He must needs be stone-blind, that sees not Churches standing without it. He must needs be made of iron, and hard hearted, that denys them salvation. We are not made of that metal, we are none of those Ironsides… (24)

Du Moulin was understandably upset: “Great Sir, I appeal to your equity. Think with your self, what streits you drive me to…[I could not] say that the Primacy of Bishops is by Divine Right but I should brand our Churches, (which have spilt so much blood for Christ) with Heresie” (36). Besides, he argued, not every apostolic practice was divinely ordained—“S. Paul in I. Timoth. v. would have Deaconesses appointed in the Church: But this fashion was long ago out of date” (34)!

Both clerics repeatedly insisted that the other consider his church’s circumstances. Andrewes implied that the King had heard Du Moulin’s arguments before in an English context—“They have long since on all hands been rounded in His ears” (8). Andrewes noted that Du Moulin wrote that his defense of episcopacy

should incur the censure of your Synod…In this We pardon you, and demand the like pardon from you; that it may be lawfull for us also to defend our Government, as becometh upright honest men. For we likewise have froward adversaries; and there are consciences, too, among us, which we may not suffer to be shaken or undermin[e]d… (9)

Yet Du Moulin, as “a French man, living vnder the Polity of the French Church, could not speak otherwise” (5). His church did not have the support of the state like Andrewes’ did, and furthermore was up against formidable Catholic enemies: “you should have considered with your self, whom I have to deal with. I dispute against the Pontificians” (31).

Du Moulin and Andrewes shared many of the same contacts (notably King James and the Geneva-born scholar Isaac Casaubon). Their correspondence–the fact they were in touch in the first place– reveals the real possibilities for communication between people of different faiths in an increasingly confessionalized Europe. Yet in their letters we can also see the limits that national and confessional context imposed on ecumenism. Local polemics—French inter-confessional arguments as well as English intra-confessional conflict—became the source of international disagreement between Protestants.

March 4, 2015 at 9:08 pm

A rich and insightful account of communication, conflict and the problems of communion in the Protestant Republic of Letters. Many thanks for bringing all this together so elegantly, and bringing up the very relevant question of cultural translatability. It’s especially fascinating to see how aware both Du Moulin and Andrewes were of what one might call the historicity of their respective churches. (On the other hand, this could be exaggerated: Du Moulin’s application of it to the question of the Deaconesses of 1 Tim deserves a special place in that grandest of imaginary folios, the Annals of Bad Exegesis.)

I’ve always found Du Moulin a bit of a mystery. Pattison tells the story of his relations with Casaubon in his usual brilliant, dramatic fashion: but the notes in Casaubon’s copy of Du Moulin’s Defense de la foye catholique (1605) (BL 852h3) tell a slightly more complex story, and Du Moulin’s 1607 B. Gregorii episcopi Nyssae de euntibus Ierosolyma epistle has more in common with Scaliger and Casaubon than Pattison would lead one to expect.