By guest contributor Devani Singh

Amongst the incunabula or “cradle books” – those produced before 1500, in the infancy of printing – currently on display at the Cambridge University Library is a more recent manuscript. It is an autograph copy of Carol Ann Duffy’s “Hypnerotomachia Poliphili”: a response, in verse, to what the Poet Laureate dubs the “the world’s most unreadable text” of the same name, a dizzying amatory dream narrative printed in Venice in 1499. Like the sonnet response to the book penned by sixteen-year-old Sisto Medici (1501/02 – 1561) on this copy’s title page, Duffy’s poem is an homage to the human relationship with early printed books and texts. “How we know what we love—”, Duffy’s poem wonders, “what we make, or hold, or pass on with our hands”. In this exhibition, “The Private Lives of Print”, focused as it is on celebrating not only the technical achievements of the first European printers, but also books’ subsequent reinventions in the hands of later owners, such lines might serve as an anchor for thinking about encounters with the products of the hand-press period, historical and recent.

England’s first printer, William Caxton, was a mercer by training; he learned the technique for printing books in Cologne, planning to incorporate these new goods into his mercantile business (ODNB). The items that he printed in Flanders supplied the English market abroad with the first books produced in the language. And the texts on display at the University Library confirm that many of the books he and his contemporaries made were intended to travel. Incunabula moved along the familiar Continental trade routes, tracing paths that Caxton had travelled to sell his wares —perhaps even manuscripts — long before he acquired a printing press (ODNB). From printing house to illuminators and binders, from authors to patrons, and from readers old to new, the striking mobility of the early printed volume at the hands of historical agents is underlined here.

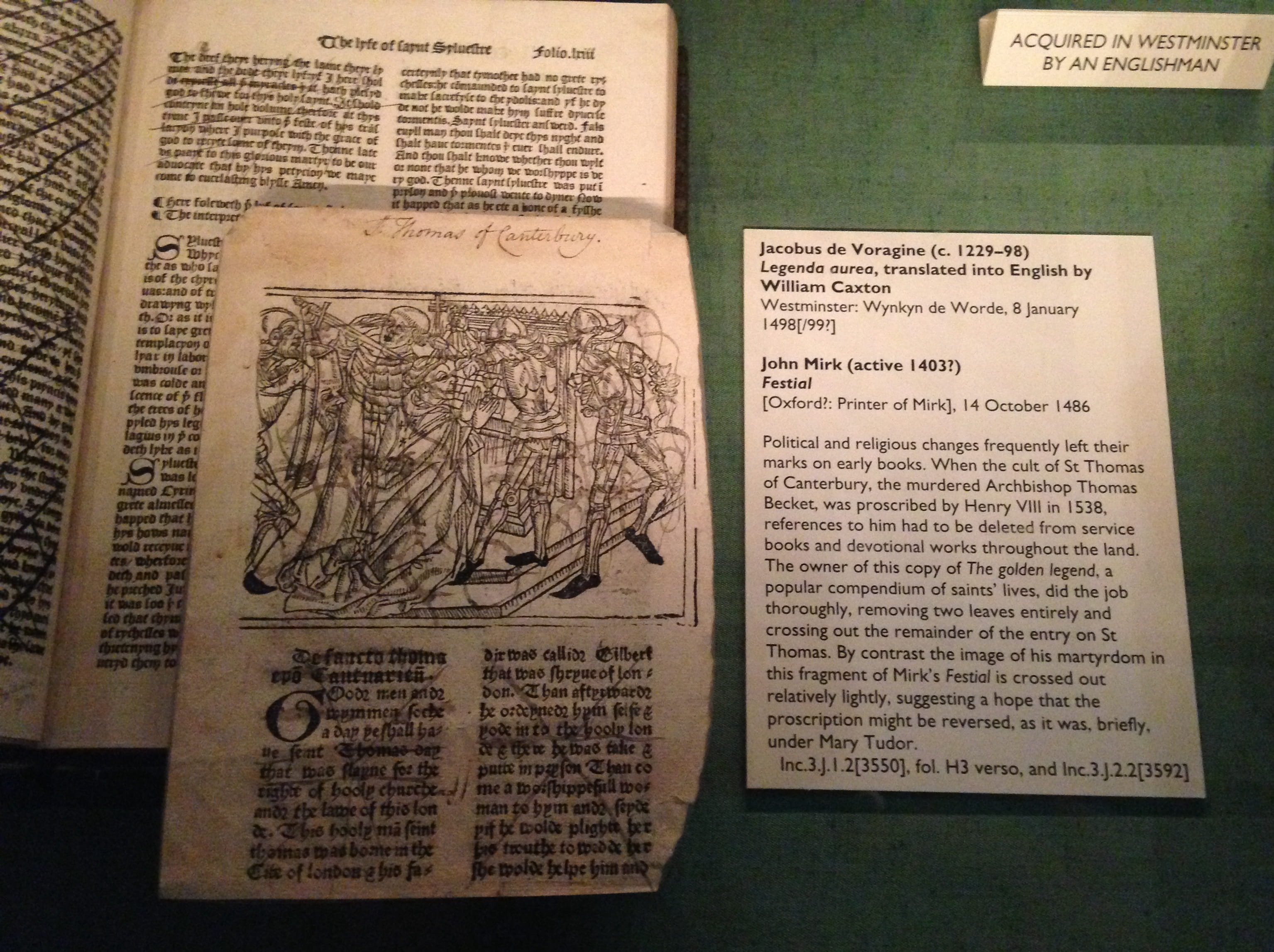

One of the exhibition’s centerpieces is a Gutenberg Bible (Mainz, 1455), once used to set copy for a Latin Bible printed in Strasbourg around 1469/1470, and here displayed alongside its exemplar. Paul Needham, who discovered the relationship between these two books, contributes an essay to the CUL’s virtual exhibition, recounting a remarkable narrative of this Gutenberg Bible’s early history that unfolded even as it sat unsold for over a decade (see also his essay here). When early printed books did reach the hands of purchasers, of course, they were often modified further, sometimes irreversibly so. One of the exhibition’s English books is a translation of the Legenda aurea, printed in London by Wynkyn De Worde around 1498/1499. Preserving an act of later censorship, this copy bears a lattice of dark ink across the remaining pages of the life of St. Thomas of Canterbury — the “hooly blissful martyr” of Chaucer’s Tales — whose cult was proscribed in 1538 by Henry VIII.

Some readerly interventions, on the other hand, have been reversed by the classifying tendencies of modern libraries, as in some of Caxton’s works on display: The Boke of Curtesye and Anelida and Arcite, once bound together with six other pamphlets into a reader-assembled composite unit. This volume saw its constituent parts separated into distinct codicological units at the University Library in the mid-nineteenth century (Gillespie, “Poets, Printers, and Early English Sammelbände”, 195). Here, an attempt is made to restore the pamphlets’ earlier configuration, as the curators return the eight booklets to proximity, inviting us to imaginatively reconstruct their existence in prior centuries as a single book.

Both edifying and divertive acts of reading are documented, sometimes in the same volume, as in a popular Latin volume on the Trojan war printed at Messina in 1498 composed of Dictys Cretensis’ De bello troiano and Dares Phrygius’ De excidio Troiae historia. One reader rendered full-page ink drawings of Roland and Hector on the book’s endpapers, transcribing additional Latin verse alongside them. But most visually arresting, perhaps, are not the drawings and dense annotations added to some books, nor even the sumptuous professional gilding and hand-coloured woodcuts that adorn the more lavish volumes in the collection, asserting the reliance of the new trade in printed books on familiar ways of beautifying them.

Rather, the eye is drawn to a group of books near the far end of the Milstein Exhibition Centre, showcasing a range of bindings in which contemporary owners covered their books. Their descriptions alone evoke the bindings’ sensuous quality — for instance, that of the delicate humanist knot-tooling on a black goatskin binding of Cornelius Nepos’ Vitae Excellentium Imperatorum (Venice, 1471), or of the pink-stained alum-tawed sheepskin that encloses a monastic copy of Cicero (Cologne, 1472). These tangible relics of previous owners and past readings permit an imaginative encounter with the people who made, cared for, and used these volumes, and with the myriad motivations these historical agents brought to their encounters with the leather, metal, wood, paper, ink, or vellum that comprise the books seen here.

The frisson that we experience from our own encounters with material texts is no doubt heightened by an awareness of their movement across time and through unknowable pairs of hands — what Duffy’s poem calls “the human chain”. That early printed texts often preserve both the intentionality and idle whims of their makers and readers is a substantial facet of their attractiveness.

Yet the CUL incunabula also speak productively of absences. One composite volume of three texts printed at Louvain in the 1480s tells of another type of chain — this one physically lacking, but evident from holes in its distinctive binding. This missing chain tethered the bound book to a lectern, probably in a Cambridge library, in the late fifteenth century.

In the case of this Cambridge book, in the compilation described above, or in the sole extant leaf of a broadside almanac offering guidance of the appropriate purging regimens for a given place (Budapest) and a given year (1475), we encounter early printed books and texts differently than their first readers did. The text of broadsides like this one would lose utility and thus, value outside of their localised geographical and temporal contexts, and were likely recycled for their physical material. This ephemerality is instructive, and grants the space to interpret archival absences. In doing so, we might better apprehend the loss, mutability, and destruction — both intentional and inevitable — that necessarily characterise the history of early printed texts.

Private Lives of Print: The Use and Abuse of Books 1450-1550 is curated by Ed Potten and is on display at the Milstein Exhibition Centre, Cambridge University Library, until April 11, 2015.

Devani Singh is a Gates Cambridge Scholar completing a Ph.D. in English at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where she is studying early modern readers of Chaucer’s printed editions. She is also interested in Renaissance historiography and in early modern uses of medieval books and texts.

1 Pingback