By guest contributor Jeremy Bleeke

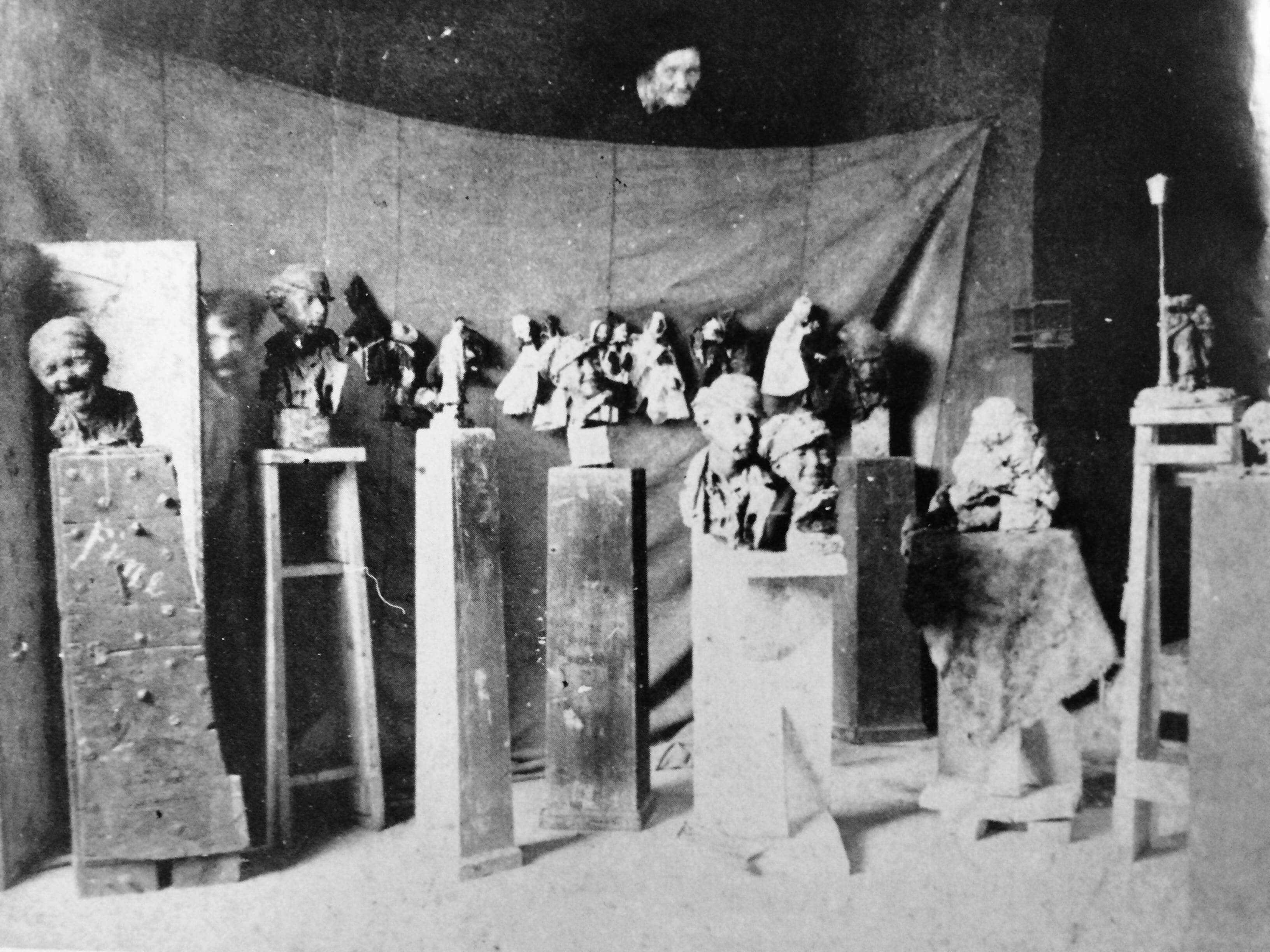

Rosso in his studio in Milan, 1883. From Margaret Scolari Barr, Medardo Rosso, Museum of Modern Art, (1963), 18.

The life and work of Medardo Rosso (1858-1928) has traditionally been divided by scholars into two phases: an initial period of creative fecundity, and a late period characterized by processes of reproduction, repetition, and copying, generally seen as a failure of imagination and vitality. From the final two decades of the nineteenth century until 1906, the sculptor created around 50 subjects in various media (characters such as the Procuress, the Sacristan, the Laughing Woman, and the Jewish Boy); Rosso then ceased to make “new” sculpture, and until his death he was mostly involved in recasting and promoting existing work. Recently, however, art historians have begun to challenge this schema, demonstrating ways in which serial production spanned Rosso’s oeuvre and challenging the dichotomy between phases of authentic originals and derivative copies.

In 2003, an exhibition titled Medardo Rosso: Second Impressions focused exclusively on Rosso’s work after the so-called end of his creative period in 1906. The show assembled series cast in different materials and uncovered the methods by which Rosso produced them. The curators found, for example, that Rosso cast with wax in the same way that he cast in bronze: working from a plaster mold that had been created from a clay model. Rosso’s fascination with “the range of possibilities inherent in the nature of the casting process” became clear.

Several years later, Francesca Bacci published a portion of her exhaustive study of Rosso’s photography (the subject of her doctoral dissertation), illuminating a facet of his production that had been largely ignored or misunderstood (Bacci, “Sculpting the immaterial, modelling the light: presenting Medardo Rosso’s photographic oeuvre”). Bacci argues that in the two decades before his death, Rosso was in fact highly productive, using photography to explore certain cherished methodologies and techniques that he had developed in his sculptural practice. For example, Rosso was famous for insisting that his sculptures must be viewed from one angle, as if they were paintings. As Bacci notes: “This viewing modality is the visual equivalent of observing a flat object. Because a photograph is an exact two-dimensional representation of an image perceived from a unique point of view, the best visual translation of Rosso’s aesthetic theory lies in the photographs of his own sculpture” (Bacci, 223). Bacci argues that the photographs are not means to an end (studio aids or documentary evidence) but stand-alone works of art.

As this new wave of scholarship suggests, Rosso (like his contemporary Rodin) was fundamentally concerned with a discourse that would become one of the main strands of twentieth-century art history and theory: the relationship between an original and its copies. So far in advance of the later conceptual games of Andy Warhol, Cindy Sherman, or Sherrie Levine, Rosso’s play with casts, copies and photographs has a freshness and innocence (born partially out of the relative youth of photography in his day) that is at once surprising and challenging. Far from seeing serial production as a repetitive exercise of duplication, Rosso opened a dialogue in his final decades between the sculptural and the photographic, using each medium to enrich one’s experience of the other.

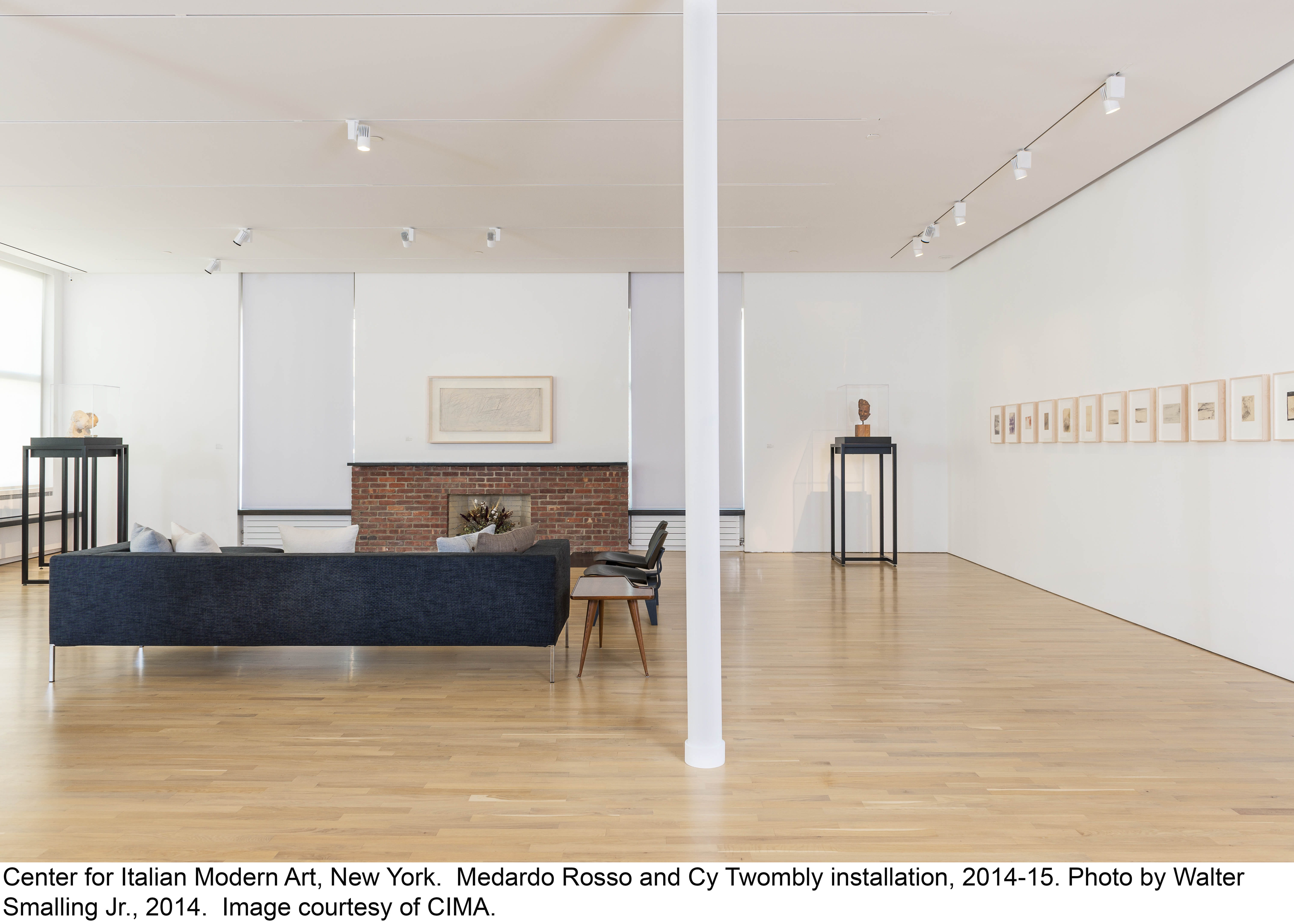

Now, at the Center for Italian Modern Art in New York, an elegant exhibition of Rosso’s work explores the long-overlooked photographic dimension of the sculptor’s research and its relationship to his sculpture (a sister show, also drawn from the holdings of the Rosso museum in Barzio, Italy, is being staged concurrently in Milan). The CIMA show brings together 11 sculptures, dozens of drawings, and over 50 original photographs taken by the artist. While we wait for CIMA to publish its research on the photographs and sculptures, a visit to the exhibition immerses the visitor in the physical evidence of the sculptor’s highly singular creative process.

CIMA, which opened in SoHo in 2013, occupies an airy, uncluttered suite of rooms; filled with light and beautifully renovated, it is a rare, uplifting space for viewing art. Stepping off the elevator, visitors are met with Rosso’s photograph Impression of an Omnibus (1884-89) taken of a plaster sculpture, now destroyed, depicting five people arrayed side by side. In a vitrine below this image are series of photographs made from it: individual fragments in which one of the characters is subjected to an array of different treatments. In one series Rosso focuses on the young woman second from the left, photographing and re-photographing existing prints of the sculpture. The result is a subtle process of abstraction, in which the figure is pared down to its essential form. From one image to the next, the woman transitions from solidly present – part of the plaster mass that is visible around her – to suggestively dematerialized. Rosso crops her more closely, and the act of re-photographing washes out the picture, so that the shadows around her face and head are all that distinguish her from the white background. In her focused, straight-forward gaze, we are reminded of the description of Clarissa’s daughter in Mrs. Dalloway, whose ride on the roof of a London omnibus might read as an ekphrasis of this image: “the breeze slightly disarrayed her; the heat gave her cheeks the pallor of white painted wood; and her fine eyes, having no eyes to meet, gazed ahead, blank, bright, with the staring incredible innocence of sculpture.”

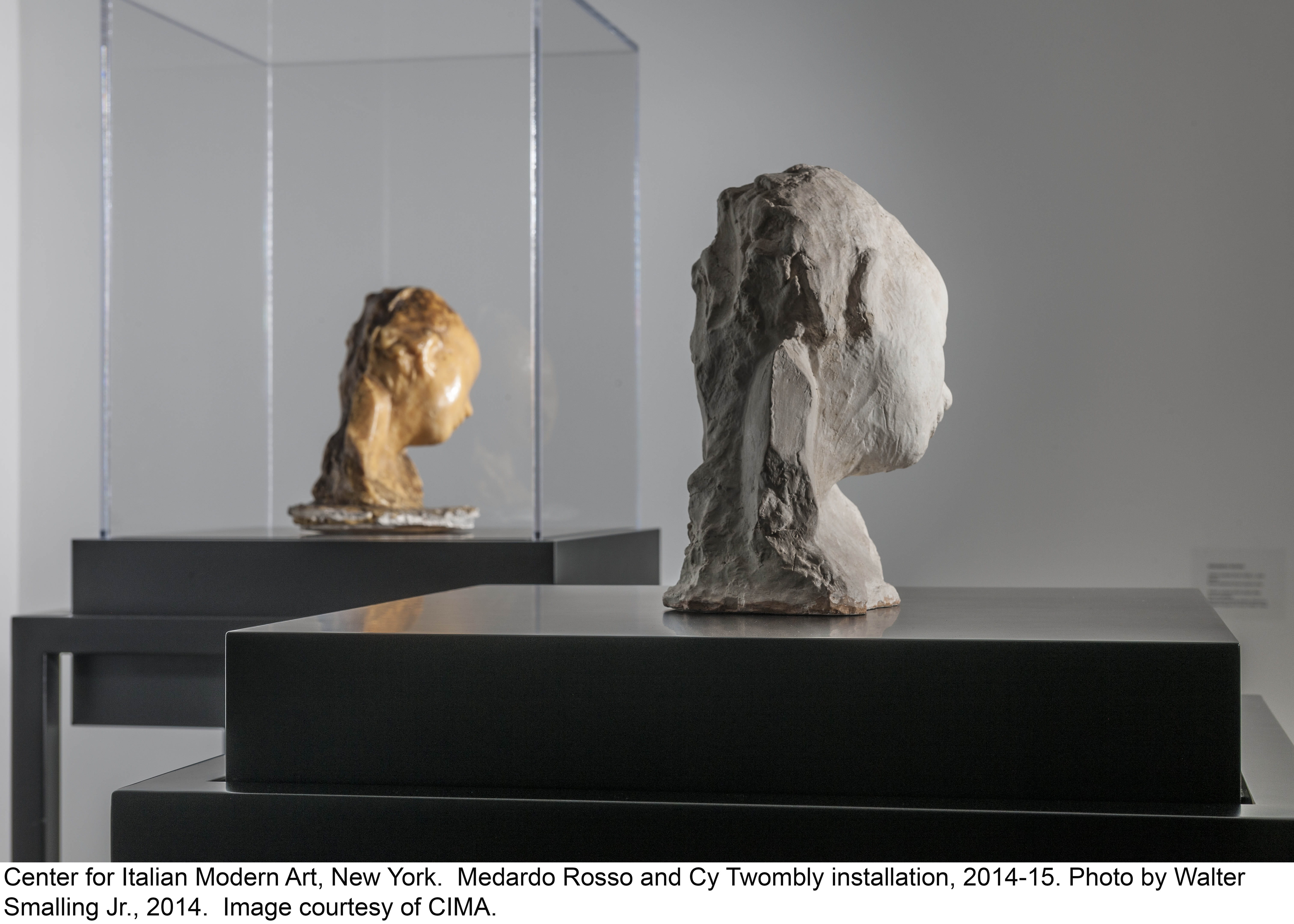

Moving into the main exhibition space, we see serial production take familiar form in Rosso’s sculpture, most notably in three iterations of the Madame Noblet, executed between 1897 and 1914 in plaster, bronze, and wax over plaster. Playing with imitations of materiality, Rosso gives the lightweight substances of plaster and wax heft and solidity, as if they are rock from which Madame Noblet has been hewn. Two versions of the Sick Child, in wax and plaster, provide a foil to the roughly handled heads. Here, the amber wax that covers the child’s face seems as delicate as skin itself. The nearby series of photographs open a provocative dialogue with these sculptures. Just as the photographic images were formed through a temporal process of exposure onto a negative, so the sculpture seems to act as a kind of receptacle of the light, becoming sharper or more diffuse depending on the ambient conditions. In the rooms of CIMA, flooded with natural light, Rosso’s play of materials can be appreciated to best effect. As the cold light of morning transitions to the golden light of early evening, these sculptures, which seem to absorb and radiate the light, must transform in fascinating ways.

For visitors relatively unfamiliar with Rosso the exhibition is filled with revelations, from near-abstract graphic works to an early experiment in photomontage. There is the shock of Conversation (1903), a plaster that just barely suggests human forms, while achieving an almost Rococo effect in its play of whispers and glances. Its baroque modeling, in which the figures rise out of a writhing bed of plaster, anticipates Lucio Fontana’s plasters and ceramics by decades. In the kitchen, a new series of prints from old negatives show Rosso exhibiting at the 1900 Exposition Universelle and the 1904 Salon d’Automne in the company of such modern masters as Cezanne. Richly detailed images of his Paris atelier round out the collection.

It is rare to see a show whose content and presentation – so thrilling yet so humble – complement each other as well as they do here. A broad passageway, in which many of the photographs are displayed, links the main exhibition space with two smaller galleries. The photographs invigorate our experience of the sculptures and drawings and unite the space by showing us the work through Rosso’s eyes. The rooms are not subdivided by genre, medium or date, and thus display a body of work that feels holistic while never becoming predictable. Without bombastic wall text and overblown claims, CIMA allows the work to speak for itself. Its insights unfold quietly, deliberately, as gradual as sunlight that slowly shades from afternoon to evening.

Medardo Rosso, at the Center for Italian Modern Art in New York City, can be viewed by appointment on Fridays and Saturdays. It runs through June 27.

Jeremy Bleeke studies twentieth-century art with a particular focus on European modernism and post-modernism. He received his MPhil in History of Art from the University of Cambridge in 2014.

Leave a Reply