By guest contributor Saraswathi Shukla

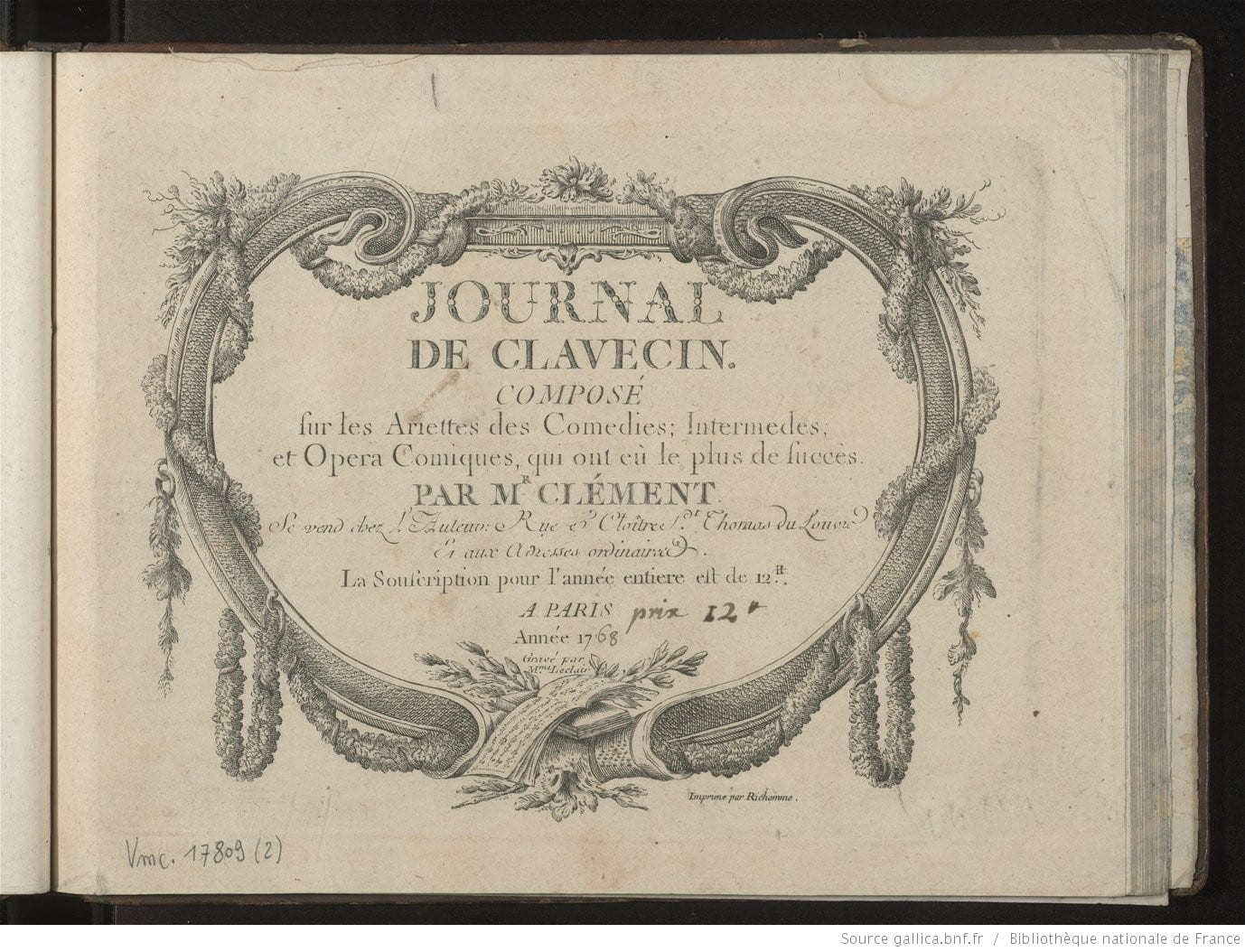

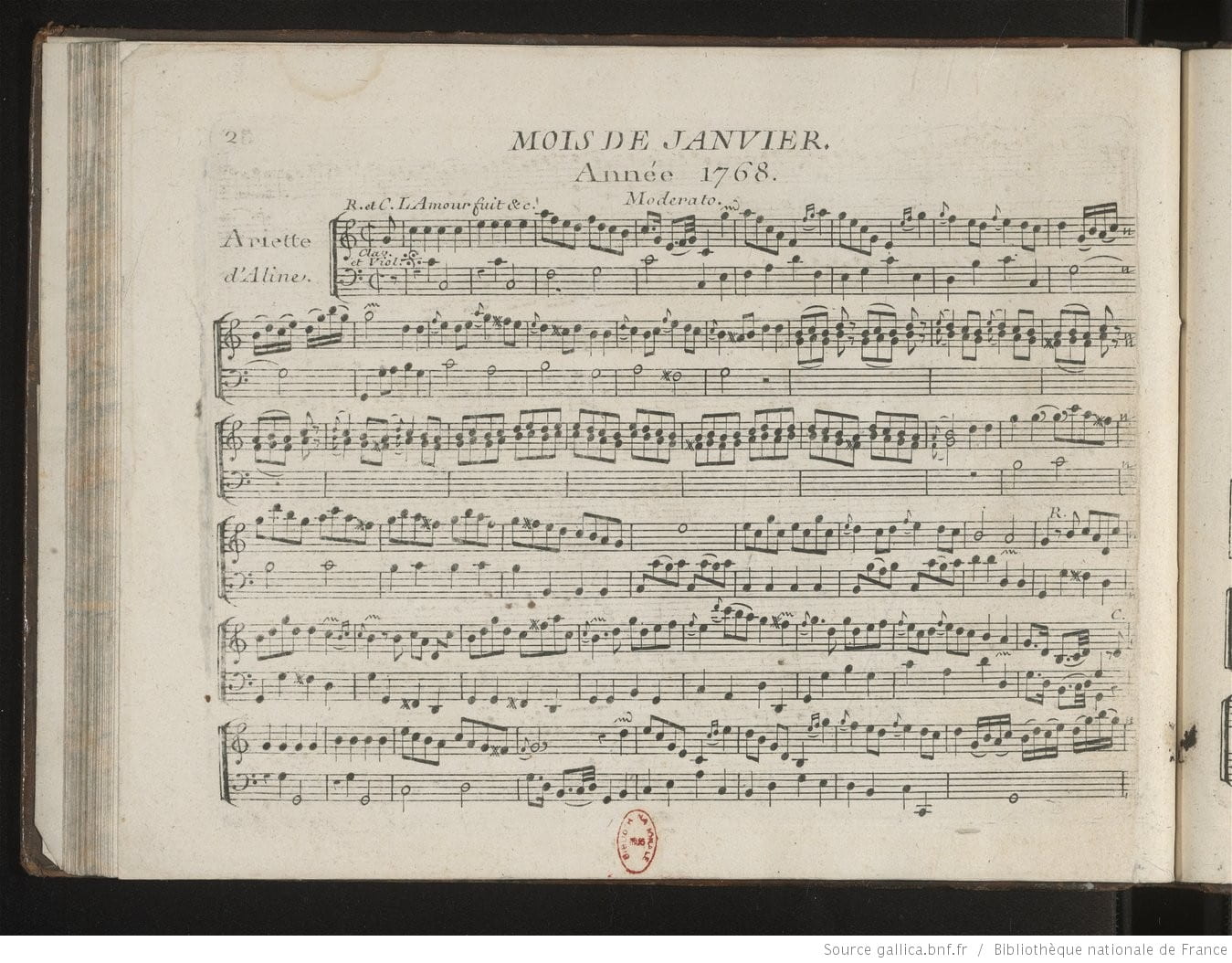

The first periodical to successfully distribute musical scores to the French public was founded in 1762 and continued under different names by different editors through the French Revolution (Bruce Gustafson and David Fuller, A Catalogue of French Harpsichord Music: 1699-1780, 1990, 17-19). In its first ten years, it ran as the Journal de Clavecin, offering its public “harpsichord pieces composed on ariettes and airs selected from intermèdes and opéras comiques which have had the greatest success.” Opéras comiques were comic Italianate operas with spoken dialogue produced at the Opéra Comique in Paris.

The publication initially consisted of harpsichord arrangements of individual opera airs grouped into “suites” of three or four on a monthly basis. The premise of the Journal was unprecedented and risky given the failure of other ventures in the aftermath of the Querelle des bouffons, the debate over French and Italian operatic styles that dominated the 1750s. Its success can be attributed to the shrewd marketing strategies of its editor, Charles-François Clément.

Clément ensured that its presentation and contents were consistently of a high quality even as other competitive periodicals emerged in its wake. Madame Leclair, a leading engraver of the day, prepared the plates, and the issues, distributed by Le Menu, were printed monthly but paginated continuously so that a single year’s issues collectively comprised 60-70 pages. (That said, no set of issues was ever bound, to my knowledge.)

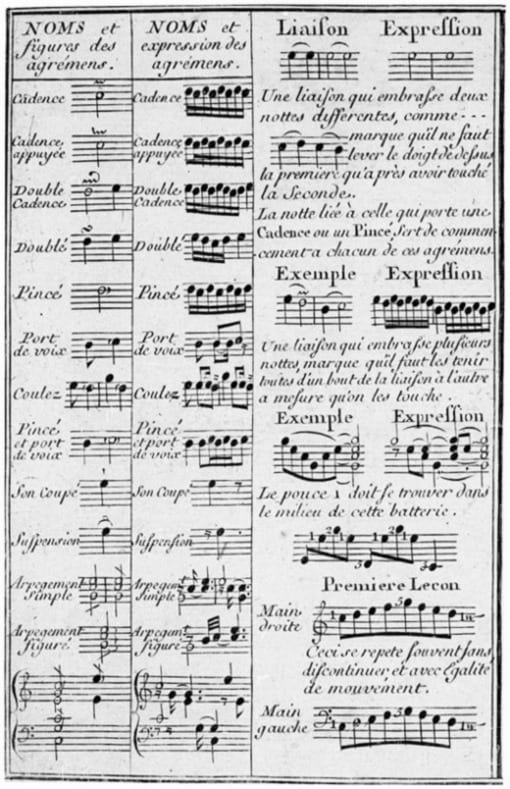

Aligning himself with the conservative harpsichord traditions of Paris may have enabled Clément to explore recent Italian musical developments without alienating factions of musical society. He embraced idiomatic French harpsichord style and ornamentation, and he adopted the typically French custom of grouping pieces into suites. Until the early 1770s, each issue consisted of two suites composed of airs from different operas instead of the traditional dance movements.

At the same time, Clément used both French and Italian tempo markings and combined airs by French and Italian composers in his suites. He sometimes labeled the left and right hands “G” (gauche) and “D” (droite) to clarify ambiguities about the division of music between the hands, a nomenclature first used in France by Domenico Scarlatti in his Italianate harpsichord sonatas (Jean Duron, “La recepción de la obra de Domenico Scarlatti en Francia,” Sevilla y corte: las artes y el lustro real (1729-1733), 2010, 313-328). Even the physical layout of the Journal was associated with Italianness in the public eye: Rousseau described landscape staff paper as “Italian” in the Dictionnaire de Musique (Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Dictionnaire de musique, 1772, 199-206).

Playing music for harpsichord with violin accompaniment, not unlike the pieces in the Journal de Clavecin. From Le Maitre de Clavecin (Paris: 1753). Digitized by IMSLP.

Although the transcriptions were intended primarily as solo harpsichord pieces, flexibility of instrumentation widened the publication’s appeal to a broader range of instrumentalists. On the title page of the first print run in 1762, Clément wrote, “These pieces include the accompaniment to their airs. They can be played on harp.” The following year, he added that they could be played ad libitum by harpsichord and violin (the violin played the highest notes). As the fortepiano gained popularity, Clément ensured that his arrangements remained compatible with both fortepiano and harpsichord: dynamics in the keyboard parts are limited to forte and piano while the violin parts feature more gradations.

Perhaps the key to Clément’s success was his ability to adapt to changes in musical style. The operas of André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry and his contemporaries prompted several musical and logistical changes in the Journal. The Journal had always presented isolated opera airs without text or context, but in its last years, it included complete vocal parts with obbligato violin and a figured bass line, representing a decisive shift away from solo keyboard repertoire. As the scores became more suitable for chamber performances of opera airs, Clément’s replaced his ariette-based suites with entire operatic scenes. Beginning in 1765, the groupings of pieces began to loosely resemble the Classical sonata, and in 1767, Clément abandoned the term “suite” entirely and stopped grouping his excerpts at all. The increasing length of each pieces probably prompted the replacement of the monthly publication of the Journal by an annual volume sometime between 1768 ad 1770.

These changes are broadly consistent with what we know of the shifts in musical aesthetics that took place soon after the arrival of Christoph Willibald Gluck in Paris in 1774 (James Johnson, Listening in Paris: A Cultural History, 1995). Could we trace parallels between the selection of “the most successful airs” printed by the Journal and the new operatic tastes of the Parisian public? Unfortunately, the shift from suite to sonata, the increasing length and changing structure of musical excerpts, the attempt to capture orchestral sound, and the inclusion of text to provide dramatic narrative predate Gluck’s arrival and influence in France. Moreover, the turnaround time between the premieres of opéras comiques and Clément’s publications often left little time for public feedback. The Journal appears not to have been printing “the most successful” works, as its title page claimed, but rather the newest works of the Opéra-Comique. So what attracted buyers to Clément’s untested musical excerpts?

One possibility sees the Journal as part of an Enlightenment project in intellectual and cultural democratization. Clément’s uncle, the Abbé Clément, was known for his commentaries on contemporary music and co-wrote the three-volume Anecdotes dramatiques, containing “histories” about the creation and production of French spectacles from its “origins” (Jean-Baptiste Lully under Louis XIV) to the present (1774). The series, the elder Clément hoped, would offer something to everyone: amateurs of opera, men of letters, women, foreigners, young people. This was a project to familiarize a new class of amateurs with the cultural currency of Parisian spectacles (Clément, i-iv).

Unlike the Anecdotes dramatiques, the Journal did not purport to teach everything about the “most popular opera airs.” The periodical was inaccessible without a musical instrument and without knowing how to read music. Still, its dedication to a fermier général, composer, and future author of L’Essai sur la musique ancienne et moderne (1780), Jean-Benjamin de Laborde, should not be taken lightly. Opera transcriptions enabled amateur musicians to engage closely with opera in ways that were impossible at the theater.

Periodicals like the Journal became viable business ventures around the time catalogues of spectacles circulated among amateur musicians and music lovers. Opportunities abounded in the 1770s for the musically inclined to build entire careers, not on performing transcriptions, but on preparing arrangements. By aiding in the formation of a new métier of commercial opera arranging, Clément handed cultural capital that had once been prized among a musical elite to amateurs and buyers of cheap music prints.

The following sound examples of ariettes from the Journal de Clavecin were recorded by the author:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/playlists/102307346″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

Saraswathi Shukla is a second-year graduate student in the Music Department at UC Berkeley. She draws on her undergraduate training in history to research the instrumental music and musical culture of 17th- and 18th-centuries France and Germany. Her research often examines the circulation of music across genres and social, geographic, and temporal boundaries.

April 28, 2015 at 1:59 pm

Your mention of Madame Leclair engraving the Journal induces me to say that I have developed an enthusiasm for the history of this ubiquitous and gifted woman, who was originally Louise Roussell, and who engraved many of the greatest works, including all of Rameau. There is a bit of interesting biographical stuff about her on the internet, including an article about the mystery of the murder of LeClair by Albert Borowitz, Finale Marked Presto: The Killing of LeClair, the Musical Quartery, 72:2, p. 228.

April 28, 2015 at 2:03 pm

In earlier work the engraving is attributed to Louise Roussel (sorry about the spelling error above), and later Mme LeClair or, sometimes, other spellings like Mme LeClerc and the like. I always had a simplistic picture of the economic roles of women in the period, as either pampered aristocrats or the downtrodden poor, or, perhaps, middle-class home-makers, but there was an entire class, it seems of up-market gifted artisans, and women seem to have been prominent in music engraving. LeClair’s body was wounded by something that appeared to have been very like an engraver’s burin, but Borowitz thinks it more likely that the perp was a parasitical nephew that the LeClairs had supported for quite some time. At the time of his death, LeClair and Louise were legally separated, but she was still delivering engraved proofs to him on nearly a daily basis.