by guest contributor Laura Quinton

Last week, New York University’s Center for Ballet and the Arts hosted a panel, “Dance and the Intellectual: Lincoln Kirstein’s Legacy.” The event featured moderator Leon Wieseltier, former literary editor of the New Republic, along with art critic Jed Perl, former New York City Ballet dancer Toni Bentley, and literary scholar and executor of Kirstein’s literary estate, Nicholas Jenkins.

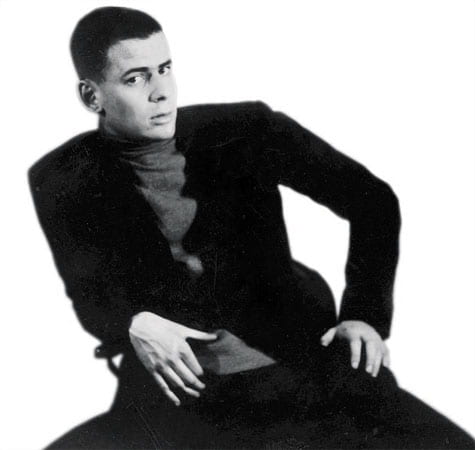

Together, the panelists described a twentieth-century American renaissance man. In addition to co-founding New York City Ballet with the eminent choreographer George Balanchine in 1948, Kirstein (1907-1996) was an early champion of and contributor to the Museum of Modern Art. As an undergraduate at Harvard in 1927, he founded The Hound & Horn, a literary publication that included Gertrude Stein and Walker Evans among its contributors. He was a prolific writer, publishing scrupulous scholarship on dance history and art history, as well as a poet. Wieseltier called Kirstein both “otherworldly” and “this-worldly,” pointing out that concepts Kirstein used to elucidate the differences between ballet and modern dance, “aerial” and “terrestrial,” were equally applicable to this enigmatic and towering figure. Moreover, he emphasized that, while Kirstein strove to encapsulate the metaphysical potential of the arts in his heady writings, this intellectual never ceased being a “man of action.”

Discussing Kirstein’s diverse tastes in the visual arts, Perl similarly noted the difficulties of pinning the impresario down. In addition to supporting mainstream modernists, Kirstein enjoyed “nitpicky realism” and defended artists like Paul Cadmus when the art establishment disavowed them. Although Kirstein often “offended canonical taste,” Perl contended that the breadth of his predilections, which ranged from innovative to reactionary, ultimately reveal “what significant taste is.” Jenkins emphasized Kirstein’s paradoxical character by comparing him to literary figures. He argued that Kirstein simultaneously embodied the “adventurous” characters of Balzac, the “oblique” ones of James, and Fitzgerald’s Gatsby: like Gatsby, Kirstein was “self-creating and self-destroying.”

With the exception of Perl, all of the participants had known Kirstein personally. Bentley shared particularly rich memories of the impresario: she recalled Kirstein’s mighty presence at the School of American Ballet and recounted dinners where he would surprise her with his latest book. Jenkins suggested that – given Kirstein’s relatively recent passing – scholars and friends of this intellectual can only now begin to fully comprehend his outstanding historical significance.

While the speakers did an excellent job explaining the breadth of Kirstein’s expertise and the quirky nuances and ambiguities of his personality, I would have liked to hear more specifically about his involvement with the dance world. More could have been said about Kirstein’s relationship with Balanchine, as well as their diverging artistic visions for City Ballet.

For intellectual historians, Kirstein’s example reveals the stimulating role dance can play in intellectual life. Ballet prompted an outpouring of rigorous historical, critical, and even philosophical writing from Kirstein. The vast historiography of dance that he produced in turn legitimized the project to establish ballet as a national high-art form in twentieth-century America. Kirstein’s efforts to institutionalize ballet in the States also helped to ensure its permanence, offering rare financial security to dancers and choreographers. Moreover, as dance historian Jennifer Homans pointed out during the Q&A, Kirstein’s artistic suggestions were crucial to landmark modernist ballets like Agon (1957).

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8bx46l2gfZ0]

Kirstein was not the only elite twentieth-century intellectual to engage with ballet. Across the pond, the economist John Maynard Keynes championed the form above all of the other arts. In 1946, as chairman of the Arts Council of Great Britain, he personally engineered the re-opening of the Royal Opera House, which featured the Sadler’s Wells Ballet (later the Royal Ballet) in a new production of The Sleeping Beauty (1890). For Keynes, ballet was “above and beyond language” (Hession, 228), and the Royal Opera House gala was “a landmark in the restoration of English cultural life” that represented “the return of England’s capital to its rightful place in a world of peace” (Moggridge, 705).

Ballet also influenced the work of Keynes’s Bloomsbury friends. According to dance scholar Susan Jones, the early-mid twentieth century witnessed a “reciprocal relationship between modernist aesthetics” in dance and British literature (10). Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes inspired new literary content and formal experimentation by Clive Bell, Lytton Strachey, and Virginia Woolf. Beyond Gordon Square, dance motivated Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot to produce works like “Dance Figure” (1913) and Four Quartets (1943).

Frequently sidelined by intellectual historians, dance was evidently a vital part of elite intellectual life in the twentieth century. Rather than eschewing dance, historians would benefit from considering intellectuals’ complex relationships with this art form: along with expanding the scope of intellectual history, such consideration might yield some surprising discoveries.

Indeed, it was fascinating to see how Wieseltier, Perl, and Jenkins, none of whom are known for their work on dance, were so inspired by and engaged with Kirstein and his dance writings. For the audience, the back-and-forth between Bentley and these thinkers presented a compelling example of how dance and intellectual inquiry continue to intersect today.

Laura Quinton is a PhD candidate in Modern European History at New York University. She researches the history of British ballet.

Leave a Reply