by guest contributor Richard Calis

In an earlier post I reported on the philological endeavors of Pieter Fontein and his strong interest in the marginalia of Isaac Casaubon. As I would like to underline here, this was much more than a story about one individual and his—rather personal—engagement with the scholarship of a previous generation. For Fontein as well as for Casaubon, Theophrastus was one of those learned authors from antiquity with whom early modern scholars were wont to converse in their studies. Machiavelli dressed up for his Livy, Petrarch admired his Cicero, Casaubon and Fontein shared their Theophrastus. A closer look at their lives illustrates this point neatly.

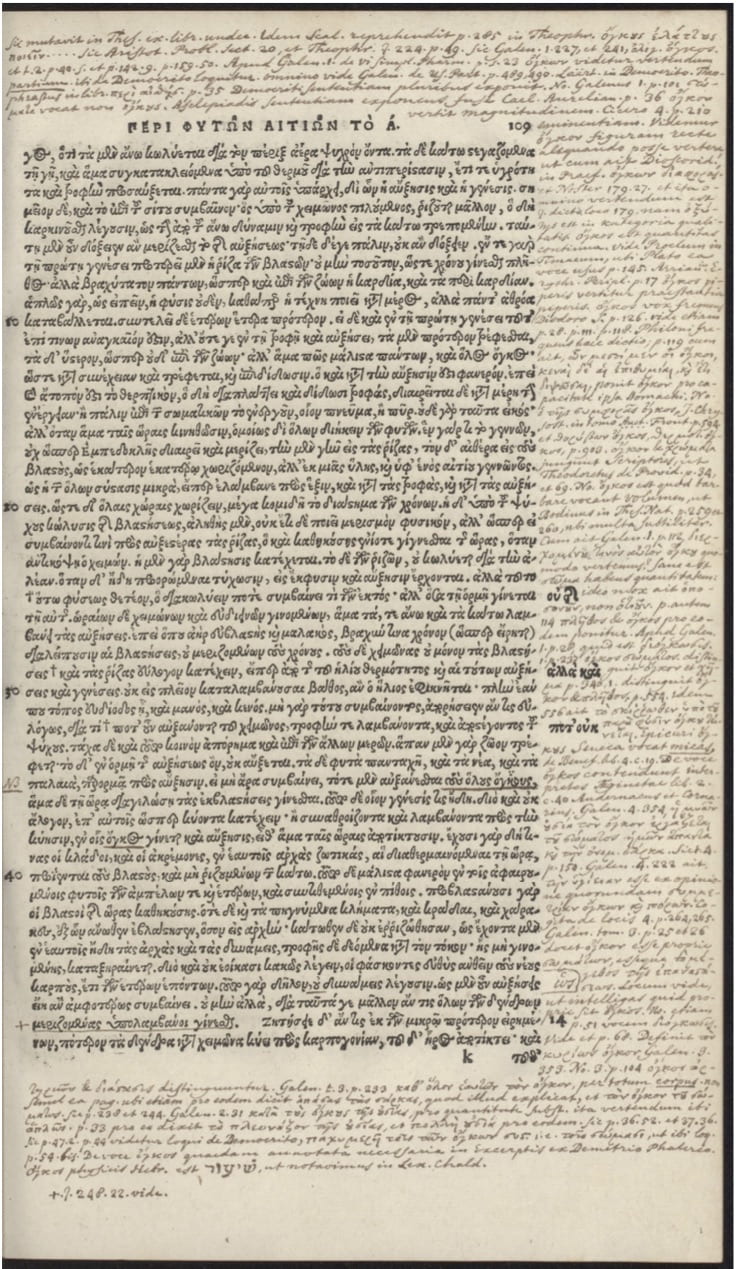

Fontein’s orderly transcription of Casaubon’s annotations. By permission of the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam. Shelf mark: OTM: Hs VII D19.

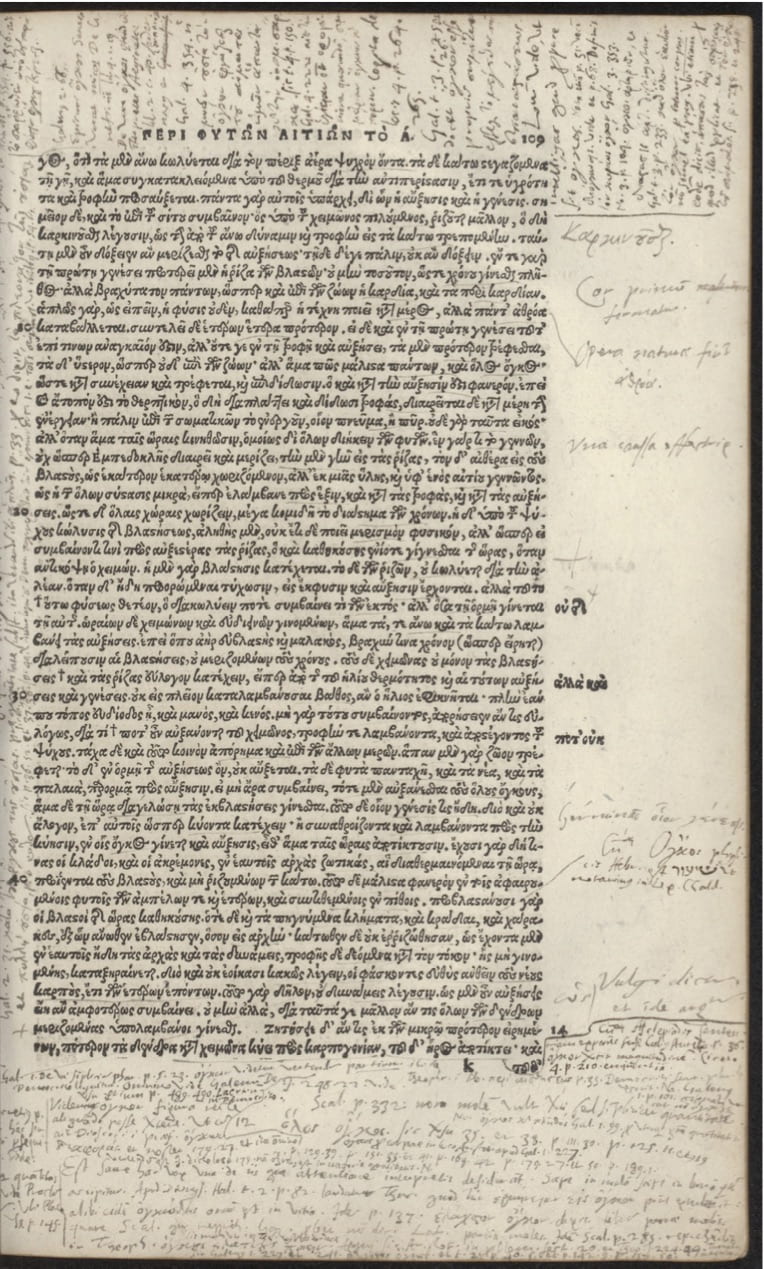

Let us first consider Fontein again, who was reading Casaubon’s marginalia when he was editing Theophrastus’ Characters. As he went through the book and copied out Casaubon’s notes, he ordered them neatly, one below the other: almost more of a copyist than a reader. Casaubon, by contrast, had scrawled out his notes all over the place in his characteristically hieroglyphic handwriting—reflecting the practice of an annotator reading with pen in hand. In decoding this handwriting, Fontein made a selection of notes that he deemed worthy of copying out. Although his exact selection criteria are still somewhat of a mystery to me—the legibility of Casaubon’s annotations is a serious possibility—many notes reveal a certain philological or lexical orientation, explicating phrases and suggesting emendations.

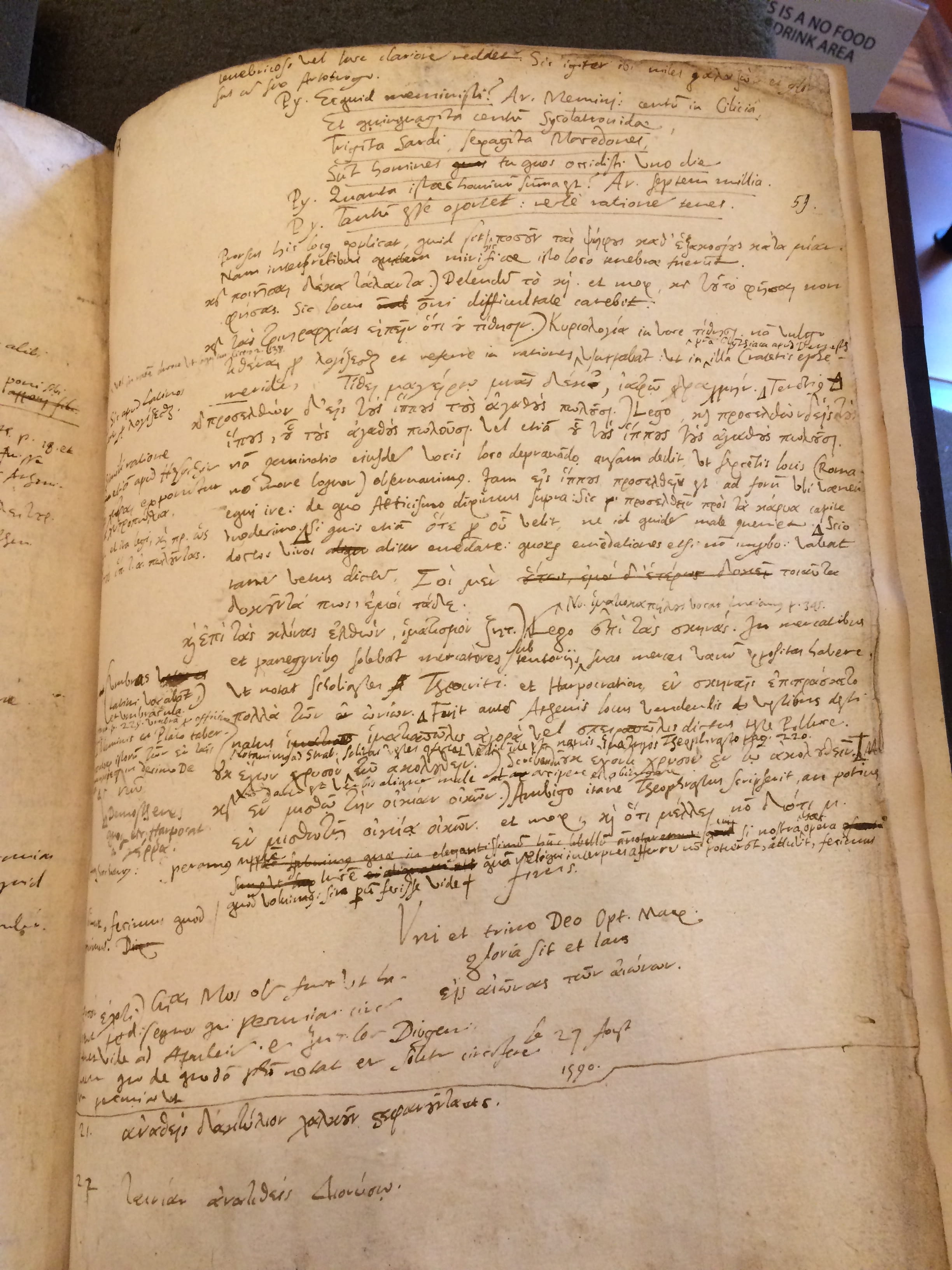

Casaubon’s scattered marginal notes. By permission of the Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam. Shelf mark: OTM: Hs VII D17.

In many ways this made sense, considering that Fontein, like Casaubon, was making an edition of an author whose textual tradition was puzzling at best and whose oeuvre included complicated works of science and philosophy. Any lexical information that could unlock the text’s philological mysteries—especially coming from one of the period’s leading authorities—must have been invaluable. But as Fontein read on and on he must have grown more and more frustrated as well. When he finally reached the Characters, found on seven pages towards the end of the book, he discovered that his sixteenth-century champion had annotated the entire book, but sadly left the treatise that Fontein was editing untouched.

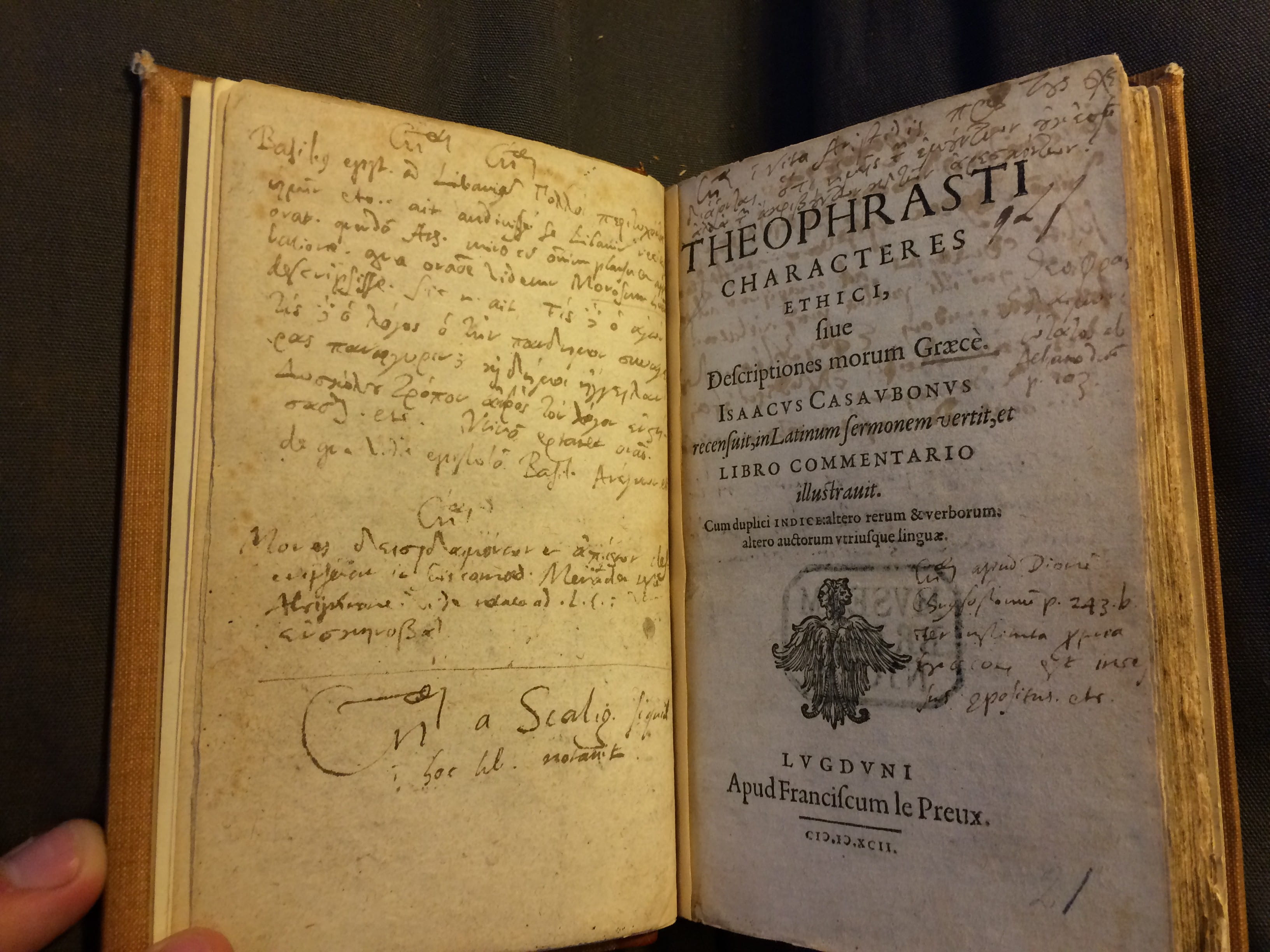

Yet the fact that Casaubon left those pages blank makes sense, too, when we realize that Casaubon was not using this book only when he had set himself the task of editing Theophrastus. In fact, the book in question is part of a larger web of paper and parchment that once filled Casaubon’s study. The first thread that we can unravel is a manuscript that is now in the Bodleian Library (MS Casaubon 7). Casaubon filled this notebook in the 1580s with what would become the draft of the edition of the Characters that he published in 1592. Furthermore, a copy of this first edition in the British Library (525.a.10.)

Title page of the 1592 edition with marginal notes by Casaubon. British Library, London. Shelf mark: 525.a.10

bears a set of handwritten corrections and additions that Casaubon himself put in the margins. Many of these marginalia, in turn, were incorporated in the second edition that Casaubon had published in 1599. And the story does not end here. The British Library also holds a copy of this second edition (1089.h.7.(2.)), containing another set of corrections and additions in Casaubon’s hand, which (not surprisingly) ended up in the third edition of the work, published in 1612.

These books thus reveal how for over twenty years Casaubon kept coming back to his Theophrastus. The work grew almost organically as he continued reading, revising, and expanding. In the 1599 edition, for instance, he included a new set of character sketches recently discovered in a manuscript in the Palatine Library at Heidelberg, while also correcting numerous mistakes from the first edition.

But this, admittedly rather technical, story of early modern scholarship is not just one about marginalia and printed editions. Intriguingly, entries from Casaubon’s diary give us a first glimpse of how the boundaries of the personal and the professional sphere blurred. In this invaluable document, Casaubon recorded his prayers, lamented the death of his friends, complained that he could not get any work done, but also listed which authors he had been reading—including, repeatedly, Theophrastus. On December 4, 1598, for instance, Casaubon lost valuable time at lunch, but decided to tackle Theophrastus’ De Causis Plantarum in the evening—”a rather precise work.” As always, this was reading with pen in hand: the emendations, suggestions, and other scribbles that he left in the margins of this text happened to be the exact same ones that Fontein so carefully transcribed some two hundred years later.

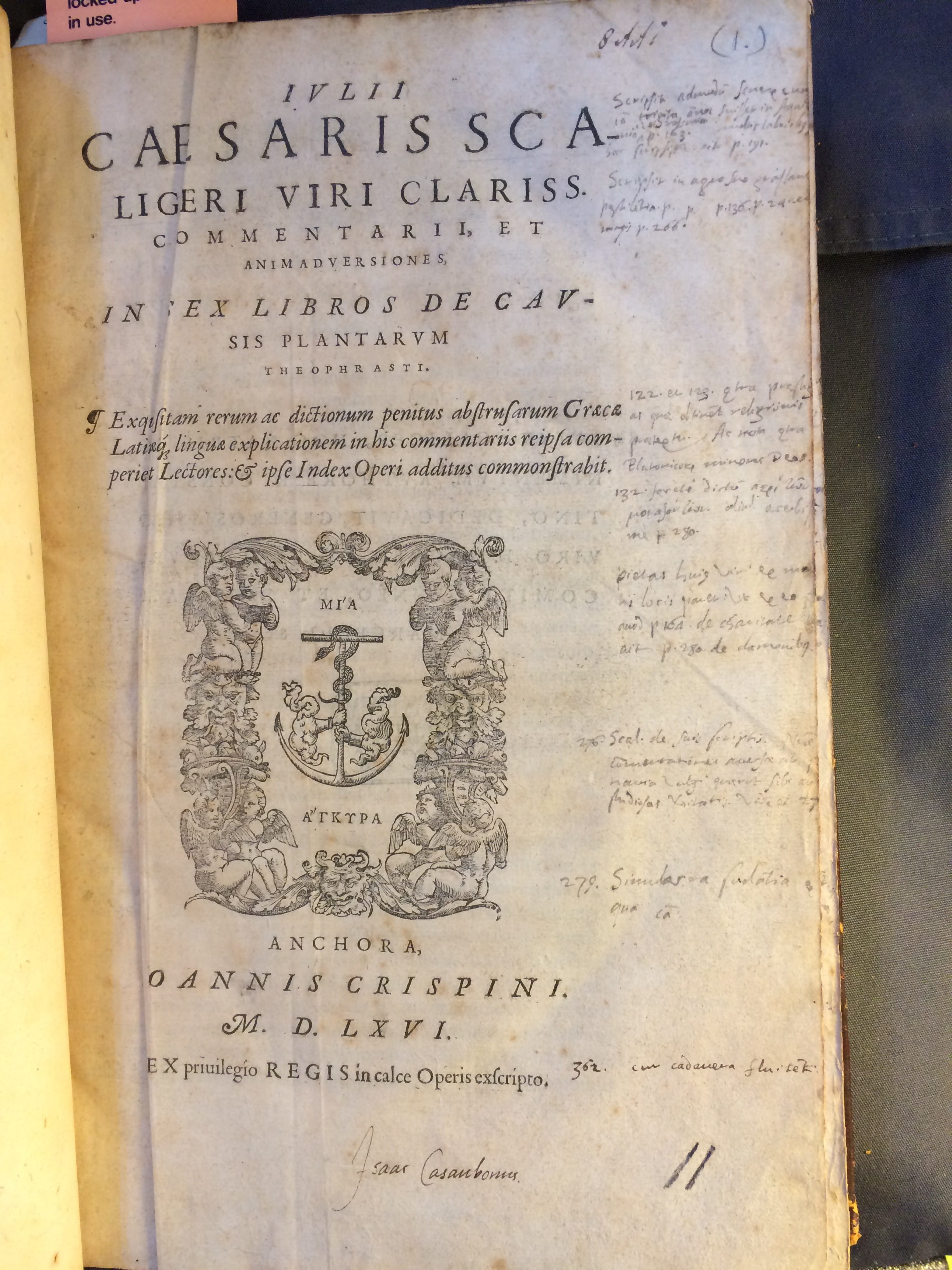

Yet what the diary does not tell us is that Casaubon also scrutinized the detailed commentary that Julius Caesar Scaliger (1484-1558), a notorious scholar of a previous generation, had written on the treatise. As he was reading the 1541 opera omnia Casaubon referenced Scaliger more than a few times in his marginal notes. These marginalia, in turn, talk to the ones that he left in his personal copy of Scaliger’s commentary (British Library C.109.p.22(1)).

Title page of Scaliger’s 1566 commentary on Theophratus’ De causis plantarum, annotated by Casaubon. British Library, London. Shelf mark: C.109.p.22(1).

Casaubon’s diary thus opens a world that the marginalia with their fragmented nature could only hint at. But it is only when read in tandem that these documents start fleshing out in considerable detail some of the laborious days and nights that Casaubon spent on Theophrastus’ works. What is more, they reveal the intimate bond that Casaubon, I believe, had forged with his ancient philosopher over the years. The physician who attended Casaubon at his deathbed recalls how Casaubon, seriously ill after having been taken on a trip to Greenwich on June 24, 1614, uttered his last words. Before a final prayer to God Casaubon remarked, with a sense of great cynicism, that Theophrastus had managed to live almost a hundred years in assiduous study, but fell ill and died after attending the marriage of a cousin. The implications were not lost on his audience.

Theophrastus thus stayed with Casaubon until the very end—as he did with Fontein, who, when his last days were nearing, kept the Theophrastiana that he collected close. And so the lives of two scholars—who were separated by centuries, but connected by a shared interest in an obscure Greek philosopher—mirrored each other in intricate ways. As they read more and more of Theophrastus’ works and of the scholarship of a previous generation, they discovered their own world and found, I would suggest, even themselves.

Richard Calis is a second-year Ph.D. student in history at Princeton University. He has worked for Annotated Books Online (@AboBooks)—which provides online access to three of Fontein’s books—and is predominantly interested in book history, marginalia, news, and the various cultures of the Medieval and Early Modern Mediterranean.

October 13, 2015 at 4:58 am

Lovely post: it’s really nice to think of Casaubon, ruminating on those vivid characters Theophrastus sketched so well.

October 14, 2015 at 12:52 pm

What’s with George Eliot’s fascination with Casaubon and Theophrastus?

October 17, 2015 at 8:08 am

Eliot’s Casaubon was based on Mark Pattison, who wrote a very influential biography of Casaubon: Isaac Casaubon, 1559–1614 (London, 1875). This story has been beautifully described in A.D. Nuttall, Dead from the Waist Down: Scholars and Scholarship in Literature and the Popular Imagination (New Haven, 2003).