by guest contributor Yitzchak Schwartz

Historians have a very specific idea of how Jewish intellectuals understood their history at the turn of the twentieth century. Most see Jewish historiography of the period as centered around the German Wissenschaft des Judentums (roughly ‘Jewish studies’). Such prominent practitioners in this school as the philosophical historians Leopold Zunz, Abraham Geiger, Heinrich Graetz for instance saw the Judaism of their day as stuck in the rut of a medieval past characterized by suffering and superstition. Many of them portrayed ancient Jewish history as pointing the way towards a reflowering of Jewish civilization in the modern period. They imagined classical Jewish history as a time before medieval Jewish legalism, the proliferation of Jewish mysticism and the institution of legal and social barriers to Jewish participation in general society.

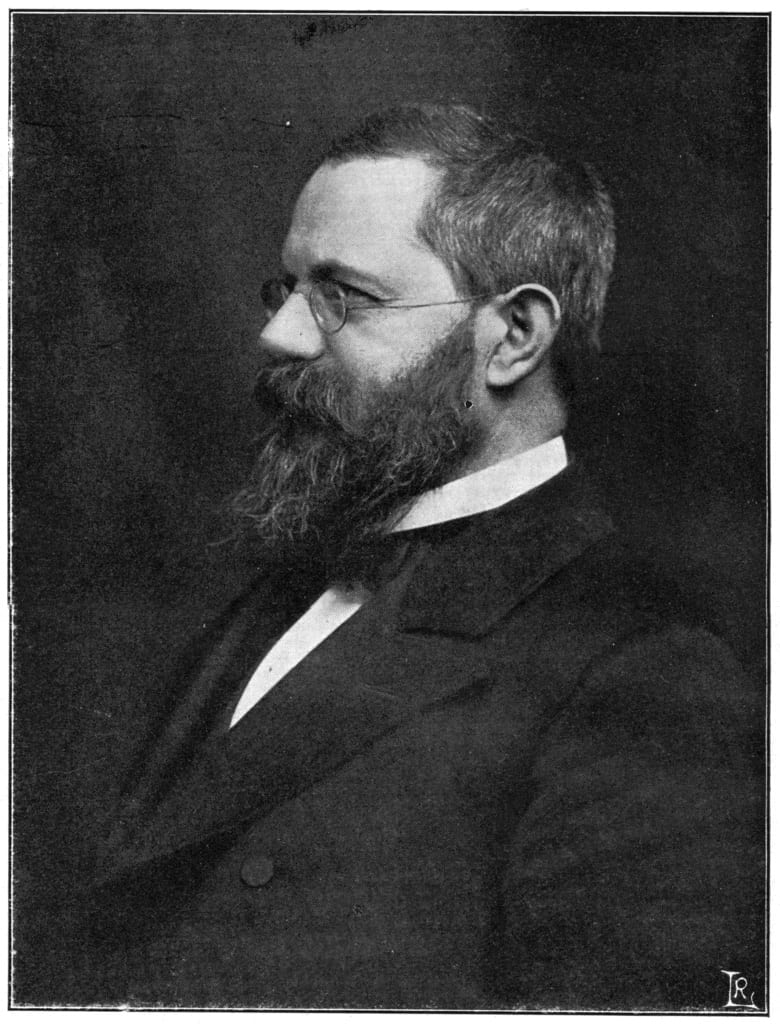

Moses Gaster (1856-1939), a Romanian-English Jewish intellectual, might serve as a model with whom we can broaden this narrative of Jewish historiography and explore alternative turn-of-the-century metanarratives of Jewish history. Gaster was both a popular and academic historian even as his work took place at the borders of academic scholarship of the period. Using the emerging discipline of folklore, his work trumpeted medieval Jewish life, legends and folklore as containing rich lessons for the Jews of his own day and as a valuable means of accessing Jewish folk culture.

Gaster was born in Bucharest in 1856 to a wealthy Romanian-Jewish Family of Austrian descent. He attended gymnasium while receiving a classical Jewish education from private tutors. Later, Gaster completed his first degree in Romania at the University of Bucharest and pursued a doctorate at Breslau, where he also studied under Zunz and Graetz at the Breslau Jewish Theological Seminary. Gustav Gröber, Gaster’s mentor at Breslau, was a philologist and pioneer of scientific comparative textual criticism in the service of philology. Gaster’s dissertation traced the history of the Romanian phenome k from its Slavic and Latin roots, incorporating folkloric materials as a means of discerning its development. During his time in Germany, he also began corresponding with Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu (as Măriuca Stanciu documents in a biographical essay on Gaster (82), the first scholar to apply the structural and comparative methods of Jakob Grimm and Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl to Romanian folklore. Before completing his doctorate, Gaster began to publish in Hasdeu’s journal Trajan’s Column (Columna lui Traia), and began authoring studies on the structure of folktales along the lines of Hasdeu’s work in various Romanian and German-language publications.

Returning to Romania in 1882, Gaster took a position at the University of Bucharest. Applying Hasdeu’s methods, Gaster began to argue what would become a major theme of his work: the idea that Jewish folklore and legends as preserved in the Talmud constituted a lost link between Romanian legends and the literature and folklore of the classical world. (A convenient summary of his work on this topic appeared in an honorary volume published for his eightieth birthday, in an article by Bruno Schindler (21-23). In 1885, after he was exiled from Romania because of his proto-Zionist activities, Gaster settled in London and was appointed Hakham (Rabbi) of London’s Sephardic-Jewish community and Lecturer of Slavonic Literature at Oxford. In England, he encountered a very different field of folklore than he had known in Central Europe. There, folklore was less established a discipline, and was primarily the province of educated laypeople organized around the Folklore Society in London. In this atmosphere, Gaster became increasingly omnivorous in the source material he analyzed, and functioned increasingly independent of any established discipline, even folklore. He also began to focus more on Jewish subjects, which became the primary thrust of his research, writing on topics as diverse as Biblical archeology, the history of the Samaritans and Jewish mysticism. He heavily involved himself in the society, serving from 1907 to 1908 as its president and publishing extensively in its journal, which featured contributions from gentlemen scholars as well as academics working in other fields.

What unified Gaster’s work was an interest in the history and ways of life of ‘medieval’ Jewry, defined as the Jews of the post-Roman to modern periods. His scholarship was revolutionary in arguing for the importance of medieval Jewish texts and practices, and especially so in its retreatment of Jewish mysticism. His interest in folk practices as sources of value in and of themselves paralleled Central European nationalist folklore studies even as it comprised a new approach in the historical study of Judaism. Gaster’s revisionist narrative of medieval Judaism is perhaps best expressed in a public lecture delivered before the Jews’ College Literary Society shortly after his initial arrival in London in 1886. In it, he expressed the idea that medieval Judaism contained treasures for the Jews of his own day, and that “This youngest among the sciences… the science of Folk-Lore…” was the means to access this rich past. He begins with an explicit challenge of the Graetz-Zunzian picture of Jewish life in medieval times, one that also challenges its focus on elite levels of Jewish society:

When we look back at bygone times and try to picture the life of the Jews within the walls of the ghetto … we see only the gigantic towers lifting their heads to the sky above… whilst all beneath them is plunged into night and darkness…. Such is the picture presented our minds when we attempt to realize the life of the ghetto. Is this picture true? The science which endeavors to answer these and similar questions is a new one… The science of Folk-Lore…. Thanks to this science we now recognize as mere legends matters which we considered as facts for centuries, and, on the other hand, many a poetical fiction… is reinstated in its rights. We look with other eyes on the heaped up treasures of Jewish aggadah [the legends and ethical teachings of the Talmud]… Brought under this new light cast on them they glitter and gleam in a thousand colors.

Gaster’s disciplinary independence allowed him to open up new directions in the study of Judaism. His acknowledgement of the importance of mysticism in Jewish life and of the vitality of the Middle Ages presaged the revolution wrought by the scholar of Jewish mysticism Gershom Scholem’s scholarship decades later. Likewise, the attention to Jewish Law as a historical source evinced in much of his work would only become mainstream in Jewish-historical scholarship after the work of Jacob Katz in the 1950s. Taken as a whole, his work suggests some exciting new directions for the study of Jewish historiography.

Yitzchak Schwartz is a doctoral student in modern history and Jewish Studies at New York University. He studies the role of popular ideas in religious and intellectual movements and narratives of history. He can be reached at yes214@nyu.edu

October 19, 2015 at 11:00 am

Check out this pic of Gaster’s Samaritan typewriter, the only one ever created! Gaster believed the Samaritans, a community based in Nablus and descended from the Northern Israelite tribes, preserved ancient Jewish texts and tradition. In the 1910s-20s he wrote a good deal about them. He created the typewriter to type his correspondence with the Samaritan priesthood. Somehow, it ended up in the Near Eastern Studies library at NYU.

https://twitter.com/maxblumenthal/status/302974685719719936

October 19, 2015 at 4:38 pm

What an appealing approach to this fascinating figure–and what a suggestive way to think about the full range of Jewish studies a century ago. Mutatis mutandis, I’m reminded of another Romanian-Jewish scholar, Lazăr Șăineanu, who also took a deep interest in non-canonical subjects. Natalie Zemon Davis spoke wonderfully about him at Columbia, a couple of years ago. The typewriter, by the way, is unbelievably wonderful.

October 19, 2015 at 10:57 pm

Thank you! Șăineanu is someone I have to look deeper into. There are many affinities with Gaster there (and also some very interesting differences).

October 19, 2015 at 4:55 pm

A well written essay, Haham Yitz. Thank you.

October 19, 2015 at 8:47 pm

I think Idel has a bit on Gaster in one of his articles on early scholars of Kabbalah. One issue with Gaster is that he often posits dates that are way too early for clearly late material, such as in his introduction to his publication of folk tales.

October 19, 2015 at 10:41 pm

As I recall Idel is a fan of Gaster’s theory of the Zohar as a collection of diverse sources rather than a composite work– a more folkloristic interpretation, I guess Like many other scholars of his time, Gaster did at times believe some of his data was older than it was and the Maaseh Bukh collection of stories is a good example. This was both because there was less comparative material to help him date more accurately and because at the time there was a hopefulness that scholars would find more definite answers to questions about the present and its relationship to antiquity. For Gaster in particular, as someone interested in Jewish folk culture, he was interested in finding ancient sources for that culture. His work on Samaritans is an example

October 19, 2015 at 11:17 pm

Șăineanu’s approach to Yiddish also involved very ancient elements preserved in relatively late traditions. Of course, occasionally this approach is right . . .