by guest contributor Peter Walker

Is it possible to be a fanatical Anglican? The idea sounds like a contradiction in terms. One readily thinks of George Eliot’s Casaubon, the stuffy and pedantic academic, or more sympathetically, Dawn French’s jolly and down-to-earth Vicar of Dibley. But Anglicans—in contrast to members of every other religious group I can think of—are never represented as “militant” or “fanatical.” They might, occasionally, be “pious” or “devout.” They are more likely to be “strict” or “staunch,” although staunchness is usually reserved for Catholics. An Anglican fundamentalist, of course, is entirely out of the question. Instead, the epithet most readily associated with Anglicanism seems to be “moderate.”

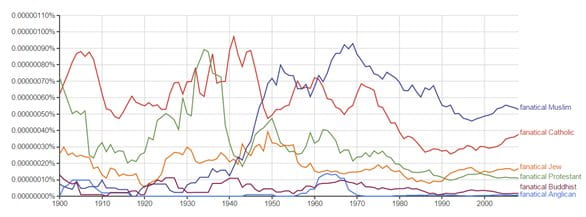

These speculations are confirmed by an unscientific dabble into Google Ngrams. Searching for the frequency of particular phrases in Google’s library of digitized books, this experiment yields the following conclusions: Protestant fanaticism ceased to be a problem in 1937. Muslims overtook Catholics as the most fanatical religious group in 1947. Fanatical Jews haunted the middle decades of the twentieth century. Only Buddhists and Anglicans have never been fanatics. The partial and intriguing exception is the 1960s, when the concept of fanatical Anglicanism seems to have held a small amount of currency. (There is a story there, which I would like to hear told.)

Ironically, Anglicanism’s very success in defining itself in terms of moderation has proved a major disincentive to scholarship on the Church of England. Who wants to study the moderate, when one can study the militant or the fanatical? The exceptions to this rule lie in those periods where the Church of England’s ascendancy was under particular threat or contention. We might look for Anglican spirituality in the nineteenth-century Oxford Movement, or in the Prayer-Book Protestants of the seventeenth-century Civil War, but never in the history of the eighteenth-century Church of England, which on this blog earlier this year Emily Rutherford called “the biggest gap in the secondary literature of all time.” Indeed, who can name an eighteenth-century Anglican clergyman? We tend to think of John Wesley as a Methodist rather than an Anglican, although the Methodist movement only left the Church of England after Wesley’s death. Jonathan Swift was a clergyman: something we tend to ignore or forget. After that, the most famous three are probably William Paley, George Berkeley, and Henry Sacheverell: hardly household names, even for historians of eighteenth-century Britain. Or perhaps the country parson James Woodforde, whose diary, discovered and published in the 1920s, is primarily a record of forty-three years’ worth of dinners. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Woodforde “seems not to have possessed a markedly religious temperament.”

The assumption has been that moderation is intrinsically inoffensive, unremarkable, and—ultimately—boring. More moderation, less religion. This assumption belies precisely what is important and interesting about the history of the Church of England: its always-contested claim to be the National Church, which entailed not just compromise and leniency but also exclusion and coercion. One of the most insightful recent contributions to the history of Anglicanism is Ethan Shagan’s The Rule of Moderation: Violence, Religion, and the Politics of Restraint in Early Modern England, which recasts moderation as a tool of social, political, and religious power, focusing on the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: in the eighteenth, he concludes, moderation was displaced and superseded by politeness (329-35). Shagan is right to note the novelty of the eighteenth-century turn to self-control and self-discipline, but even allowing for this crucial reconfiguration, the ideal of moderation remained centrally important in public life. Nowhere is this more true than in the identity of the eighteenth-century Church of England, a bulwark of moderation, defined against enthusiasm, superstition, and atheism. Moderation was a religious ideal: it did not indicate an absence of religion. It is a testament to the success of the eighteenth-century Church of England that it has become so invisible.

Peter Walker is a PhD candidate in History at Columbia University. His dissertation is about militant Anglicans.

jhiblog

9 Comments

Add yours

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

RECENT POSTS

- Marx’s Reception in the United States: An Interview with Andrew Hartman

- Spaces of Anticolonialism: Disha Karnad Jani Interviews Stephen Legg

- Announcing the Martin Jay Article Prize for Graduate Students

- The Architects of Dignity: Disha Karnad Jani Interviews Kevin Pham

- “Language and Image Minus Cognition”: An Interview with Leif Weatherby

Subscribe to receive an email notification for each new post

Completely spam free, opt out any time.

Please, insert a valid email.

Thank you, your email will be added to the mailing list once you click on the link in the confirmation email.

Spam protection has stopped this request. Please contact site owner for help.

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

October 28, 2015 at 9:59 am

Reblogged this on Progressive Rubber Boots and commented:

Oh, those Anglicans!

October 28, 2015 at 9:10 pm

Very interesting. I do work on liberal Protestants in America and I’ve also noticed how they often get left out of the more recent wave of religious history scholarship because of their moderation. In the case of the Anglicans and others I study, that moderation was also the product of liberal theology, which scholars today often find very hard to pin down using the familiar set of approaches to religious movements….

October 29, 2015 at 10:29 am

Interesting – I don’t know very much about American liberal Protestantism, but I wonder if there is a similar assumption, that moderation is ultimately “political” and therefore not properly “religious”.

October 28, 2015 at 11:10 pm

Thanks so much for this post, Peter–I’d love to hear more about your research. One question: to what extent is 18c moderation in the CoE radical (I assume it is still polemical–ie defining themselves against perceived radicalism)? Is it only in hindsight that we think of having lots of dinners as “not markedly religious”? For example, I’ve done some work on 16c bishops and the lavish meals they host are an important part of their episcopal status, continuous with medieval ideas about hospitality–a different context, of course, than the clerical dinners you mention, but still, I’m curious to hear what you think.

A second, less important question: does the idea that the church militant moves west help define the CoE’s “moderate” identity in the 18c? I’m thinking of George Herbert’s ‘Church Militant’, ‘Religion stands on tip-toe in our land, / Readie to passe to the American strand.’ It’s earlier than your period, but I’d be interested to know if there’s an afterlife to that idea, and whether/how perceptions of American religion might be shaping Anglican identity.

Thanks again.

October 29, 2015 at 10:26 am

Thanks Madeline, these are both fascinating questions! Yes, I absolutely agree that the ideal of “moderation” remains polemical and, in a sense, radical. It retains the ideological and potentially coercive aspects that Shagan identifies in the earlier period (in the 18th century you see this in the political marginalisation of Protestant Dissenters and Catholics). It also meshes with newer ideals of politeness and enlightenment, so there’s an innovative aspect as well. Your point about food is such an interesting example. The Anglican clergy are inevitably portrayed as gluttonous by their critics, but there’s also a more positive dimension to this, which is harder for us to access. Consumption could be a way of signalling one’s politeness and sociability, and of abjuring the excessive “gloominess” that was thought to characterise both Puritans and Papists. I actually posted about this earlier in the year, although I think there’s a lot more to say on the subject.

As for the church flying westward, I certainly think there’s something to this as well. 18th century Anglicans tended to see all the American colonists as prone to “enthusiasm”, the archetype being the New England puritans, but the category tended to slip and get applied to different denominations in different colonies. I can’t think of an example of this being articulated explicitly in terms of the westward movement of the church, but certainly it was understood in terms of the grand design of Providence, opening the Americas to discovery and colonization at the very moment of the Reformation, in a process that now had to be completed by the work of organizations such as the SPG.

October 29, 2015 at 10:27 am

Here is the post about food: https://peterwilliamwalker.wordpress.com/2015/01/30/the-clergy-and-food-gluttonous-hypocrites-or-agricultural-improvers/

October 28, 2015 at 11:50 pm

The question is, I think, whether ‘fanaticism’ was historically the generic term for religious extremism that it is today — equally applicable to any and all confessions and denominations. The answer, I think, is pretty clearly that it was not. The term ‘fanatic’ in the eighteenth century would have presumably been difficult to separate from the broader critique of ‘enthusiasm,’ that is, the personal religious inspiration associated with radical nonconformist sects such as the Quakers. The absence of a critique of ‘fanatical Anglicans’ in the eighteenth century, then, would be indicative not of their moderation — genuine or ideologically constructed — but perhaps of the inapplicability of that particular mode of religious extremism. Simply put, Anglican extremism rarely took the form of an excess of religious individualism, or a deficit of external authorities — political or historical. As such, that line of critique would have had precious little public resonance.

Perhaps the argument might be better served by a closer engagement with the actual rhetoric of Anglican extremism in the eighteenth century: tantivy, high-flyer, Jacobite, church and king mobs, &c.–all of which tended to imply an excessive deference toward external authority: indeed, perhaps going so far as to compromise the religious individualism at the heart of Protestantism, and thus potentially opening up on to far graver charges of popery or crypto-popery.

In the early United States, even American Episcopalians with no residual allegiance to the British Crown whatsoever, much less the will or capacity to engage in religious persecution were frequently charged with Laudianism, or compared to Laud — the arch-villain of the narrative of American religious liberty! Even in the radically transformed circumstances of an independent United States, the charge against the Anglican tradition remained that of authoritarianism, hierarchy and exclusivity.

The fact that Anglicanism in the eighteenth century was seldom liable to charges of fanaticism does not simply mean that it was either genuinely moderate or somehow more successful in ideologically seizing for itself the religious middle ground (although these may well be so). It also means that their taxonomy of religious extremism was a good deal more sophisticated than ours, which tends to operate on a one-dimensional spectrum roughly from secular to fundamentalist. Theirs, by contrast, made room for a far greater variety of religious excesses. The construction of ‘moderation’ required an active policing and de-legitimating of all of them — not just fanaticism.

October 29, 2015 at 8:11 pm

This is an interesting problem. Thanks for sharing, Peter.

The question is, I think, whether ‘fanaticism’ was historically the generic term for religious extremism that it is today — equally applicable to any and all confessions and denominations. The answer, I think, is pretty clearly that it was not. The term ‘fanatic’ in the eighteenth century would have presumably been difficult to separate from the broader critique of ‘enthusiasm,’ that is, the personal religious inspiration associated with radical nonconformist sects such as the Quakers. The absence of a critique of ‘fanatical Anglicans’ in the eighteenth century, then, would be indicative not necessarily of their moderation — genuine or ideologically constructed — but perhaps of the inapplicability of that particular mode of religious extremism. Simply put, Anglican extremism rarely took the form of an excess of religious individualism, or a deficit of external authority — political or historical. As such, that line of critique would have had precious little public resonance.

Perhaps the argument might be better served by a closer engagement with the actual rhetoric of Anglican extremism in the eighteenth century: tantivy, high-flyer, Jacobite, church and king mobs, &c.–all of which tended to imply an excessive deference toward external authority: indeed, perhaps going so far as to compromise the religious individualism believed to lie at the heart of Protestantism, and thus potentially opening up on to far graver charges of popery or crypto-popery.

In the early United States, even American Episcopalians with no residual allegiance to the British Crown whatsoever, much less the will or capacity to engage in religious persecution were frequently charged with Laudianism, or compared to Laud — the arch-villain of the narrative of American religious liberty! Even in the radically transformed circumstances of an independent United States, the charge against the Anglican tradition remained that of authoritarianism, hierarchy and exclusivity.

The fact that Anglicanism in the eighteenth century was seldom liable to charges of fanaticism does not simply mean that it was either genuinely moderate or somehow more successful in ideologically seizing for itself the religious middle ground (although these may well be so). It also means that their taxonomy of religious extremism was a good deal more sophisticated than ours, which tends to operate on a one-dimensional spectrum roughly from secular to fundamentalist. Theirs, by contrast, made room for a far greater variety of religious excesses. The construction of ‘moderation’ required an active policing and de-legitimating of all of them — not just fanaticism.

October 30, 2015 at 9:44 am

Thank you this, Brent. I completely agree with you, actually. I think the idea of “fanatical Anglicanism” sounds unfamiliar today because, exactly as you say, we don’t have anything like the same taxonomy of religious extremism. I certainly wasn’t suggesting that the Church of England’s claim to be moderate went unchallenged at the time, or that we should be looking for those challenges in accusations of “fanaticism”. As Shagan says, moderation is coercive. What looks like moderation from one perspective looks like popery or Jacobitism from another. My point, really, was that the Church of England *today* is seen as “moderate” rather than “fanatical” (on that one-dimensional spectrum) and that this perception has had a detrimental effect on scholarship on the history of Anglicanism. If the Church of England was still being accused of Laudianism, it would be easier for historians to see the conflicts, coercion, and policing surrounding its claim to be moderate in the past.