by guest contributor Elad Uzan

One of the ways in which the history of the Jewish people reveals itself is through music. The Torah, Writings [Ketuvim], and the Psalms contain over eight hundred references to the spiritual and religious usages of music. Yet the Great Revolt against the Roman emperor Vespasianus also led to the termination of the use of music for religious practices in the Temple, defining the Jewish musical reality for centuries to come.

We know of Jewish musicians before the Renaissance; however, most of their works have been lost, and information regarding Jewish musicians living before the sixteenth century is very scarce. The greatest Jewish composer of the late Renaissance—in fact, until the beginning of the nineteenth century—was Salamone de Rossi. Rossi was an innovative composer and a virtuoso violinist who was active from the late Renaissance to the early Baroque. He was a contemporary of Monteverdi, and served with him in the court of Duchess Isabella d’Este Gonzaga in Mantua, North Italy.

In 1589, at only nineteen years old, Rossi published his first work, a collection of canzonets, followed by a collection of more serious madrigals for two voices and basso-continuo. Later, he published five volumes of madrigals for five voices, and an additional volume for four voices. His further accomplishments included four collections of symphonies (instrumental introductions), canzonets, sonatas, trio-sonatas, and a variety of additional melodies, as well as music for theater and comedy productions. His instrumental compositions for chamber ensembles, among the first to be published in print, truly display his greatness as a revolutionary composer.

The young and ambitious Rossi marketed his work to a primarily non-Jewish audience and faced the limitations resulting from the divisions between the Jewish and Gentile worlds. But his creations also benefited from being influenced by both worlds, as different compositions were intended for different audiences, with fundamentally different tastes and demands, which enriched the texture and shaped his style.

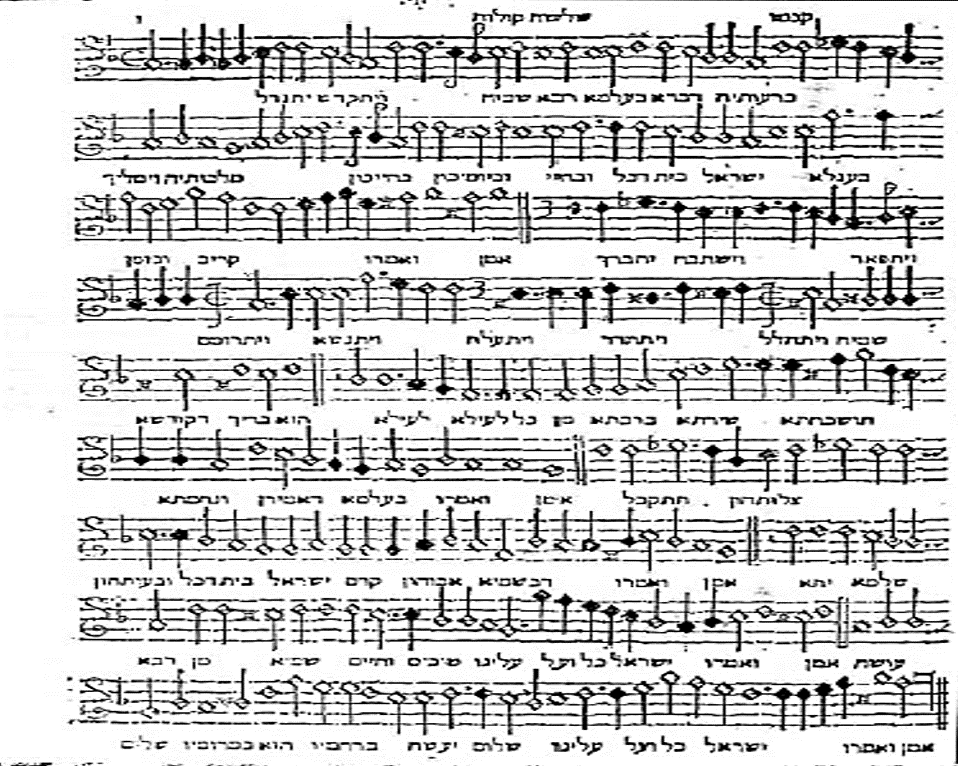

Rossi made the first forays into liturgical Jewish music, which he initially introduced with his work The Songs of Solomon. This work is the cornerstone of liturgical Jewish music: the first of its kind, written by a Jewish composer, with the text written in Hebrew and taken from the original Hebrew sources. This composition provoked community opposition from the traditional Jewish establishment, which was against the use of music in liturgy. The Songs of Solomon (Ha’Shirím ashér Li’Shlomó) is a collection of thirty-three songs, most of which contain texts from the Book of Psalms. One song was taken from the book of Leviticus, another from Isaiah, five from Jewish non-Biblical sacred and secular literary sources, and one from a wedding ode. Recently, these compositions have been performed by Profeti Della Quinta, a male vocal ensemble of Israeli musicians specializing in Renaissance and Baroque music, currently based in Basel.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=enNNDmc9PLg]

Rossi named his composition The Songs of Solomon, presumably to link it to the legacy of the Song of Songs, traditionally believed to have been written by King Solomon. Alternatively, the title also might make the reader assume that Rossi dedicated his work to King Solomon (in fact, however, he dedicated this collection of songs to himself). The choice of the Psalms also links the work to king David, traditionally believed to be their author, who was known in Jewish tradition to possess great musical talent: the “pleasant singer of Israel” (Ne’im Ze’mirot Israel).

Rossi faced three obstacles in composing his songs. The first was the opposition of the rabbinical community in Mantua to changes—especially to significant change, such as Rossi’s songs—concerning anything related to the liturgy of the synagogue. The second was the absence of a Jewish compositional tradition of polyphonic music. The third was the problematic technical issue of printing music with a Hebrew text.

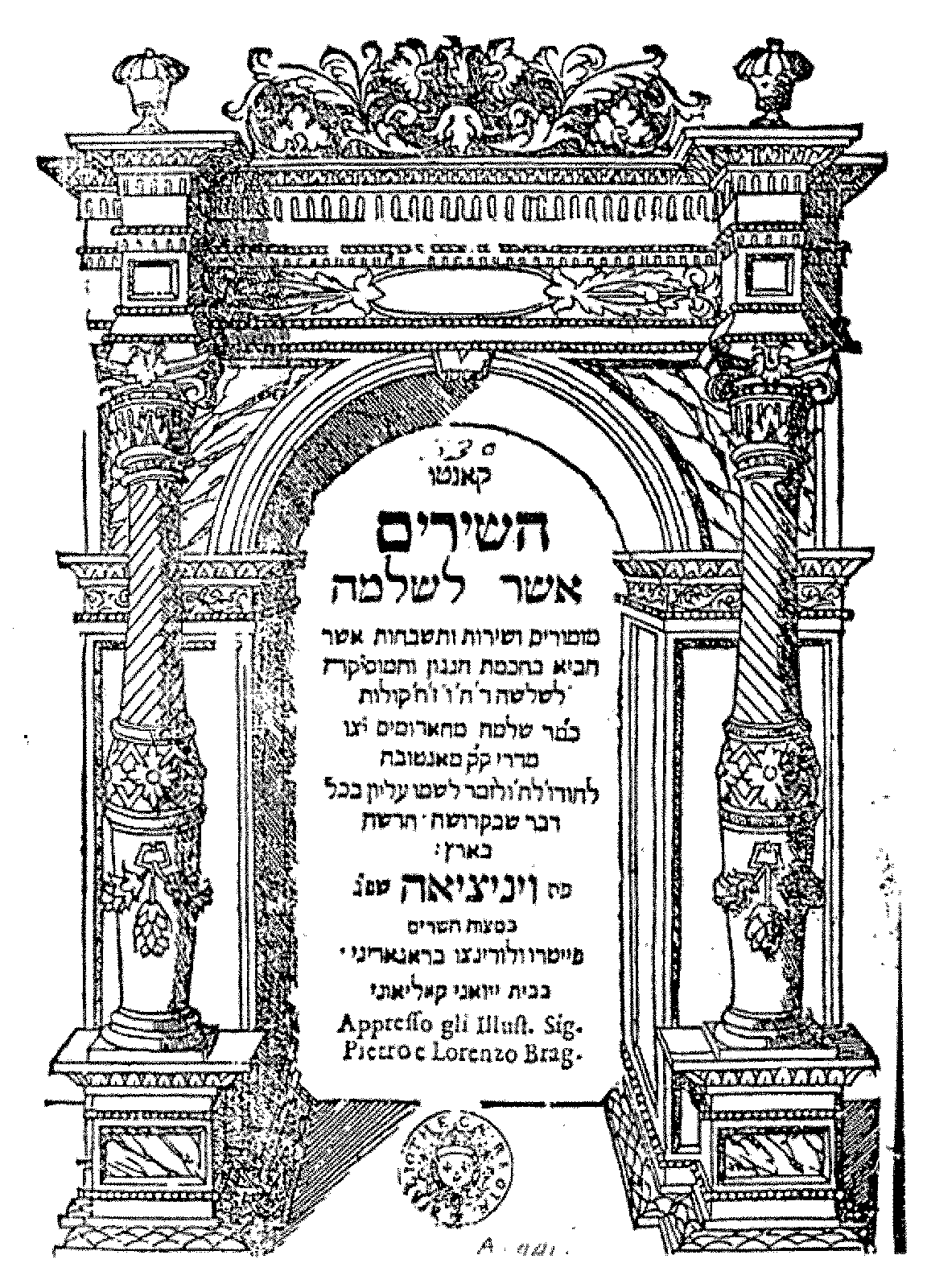

A number of introductions precede the musical scores. These serve as a preemptive apologia against possible critics. They survey various historical, sociological, artistic, and religious issues that concerned the Jewish community of that time, questions would later be reflected in the texts used by Rossi in his polyphonic composition. The title page includes a long dedication by Rossi to Moses Sullam, his patron and benefactor.

Following the title page is an introduction by the most important figure involved in the compilation and organization of The Songs of Solomon, who later helped Rossi to publicize his creations: Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh (Leone) Modena. A rabbi, sermonizer, adjudicator of Halacha, poet, musician, and sharp debater, Modena declared that at age ten, he had learned enough to “play an instrument, sing [and also] dance” (Daniel Carpi, R. Yehuda Aryeh Mi-Modena’s “Chayye’ Yehuda” (Hebrew; Tel Aviv, 1985), 41). In 1605, at the age of 34, Modena involved himself in the controversy that took place in northern Italy’s city of Ferrara regarding the presentation of Jewish music in synagogue and later published two sermons arguing for the legitimacy of using artistic music in Jewish liturgy.

The manuscript starts with an oration by Rabbi Modena that praises Rossi’s work. From there on, it deals solely with questions of religion and music. The next page includes a sermon by Rabbi Modena in which he presents the Halachic foundations of his position on a question, addressed to him in the year 1605, regarding the appropriateness of music as a component of holy activities in the synagogue. He makes use of Ketuvim, the Talmud, and additional sources in order to prove that the Halacha does not forbid—nor is there proof that there was ever a prohibition upon—the liturgical use of music: “Is it conceivable that those whom God has bestowed [the musical] wisdom and strive to honor the almighty be considered as sinners? God forbids! We would sooner condemn the shaliach tzibbur [Chazzan, Cantor] to bray like an ass rather than pleasantly sing: should they sing, it will be said about them ‘she has lifted up her voice against me’ (Jeremiah 12:8). And we, who are musicians in our prayers and praises, will now be a mockery to other nations who will claim wisdom has abandoned us, and we shall cry out to the Lord of our fathers as a dog and a raven […]”. (Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Modena, She’elot u-Teshuvot Ziqnei Yehudah [Questions and Answers the Elders of Judea], indicator 101, 36, (Shelomo Simonson edition, 1955), 18).

All this shows that the introduction of artistic music in prayer, which changed the customary liturgical tradition in synagogue, presented the biggest challenge Rossi had to face in his career. Music was associated with Christian liturgy—or, at least, with forbidden secular music. The only way in which Rossi and Modena could promote tolerance of music in synagogue was by connecting its essence to the ancient musical practice of the Levites during the time of the Temple, as Rossi did by referring back to the founders of that tradition: David the Psalmist, and Solomon the builder of the Temple and the author of the Song of Songs. Thus, Rossi could characterize The Songs of Solomon as a return to Jewish origins, defined as “to return the crown to the glory of old” (le’hahzir atara l’yoshna), rather than as a suspicious incorporation of music which has no Jewish affiliation.

Elad Uzan is a Ph.D. candidate in international law & philosophy at Tel-Aviv University’s Faculty of Law, a doctoral fellow at the ERC-funded GlobalTrust – Sovereigns as Trustees of Humanity project at Tel Aviv University, and the classical music critic of Yedioth Ahronoth.

Leave a Reply