by contributing editor Brooke Palmieri

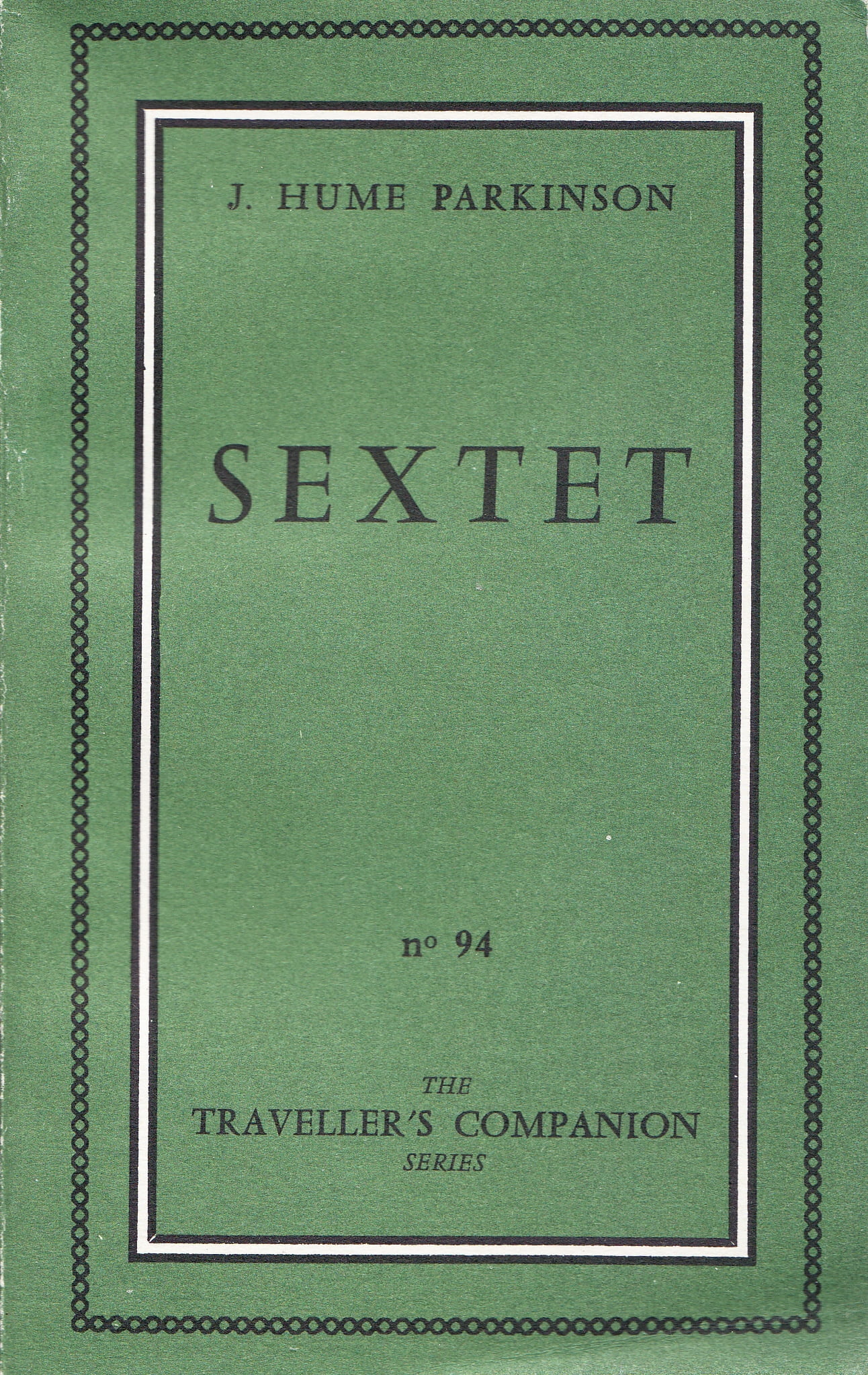

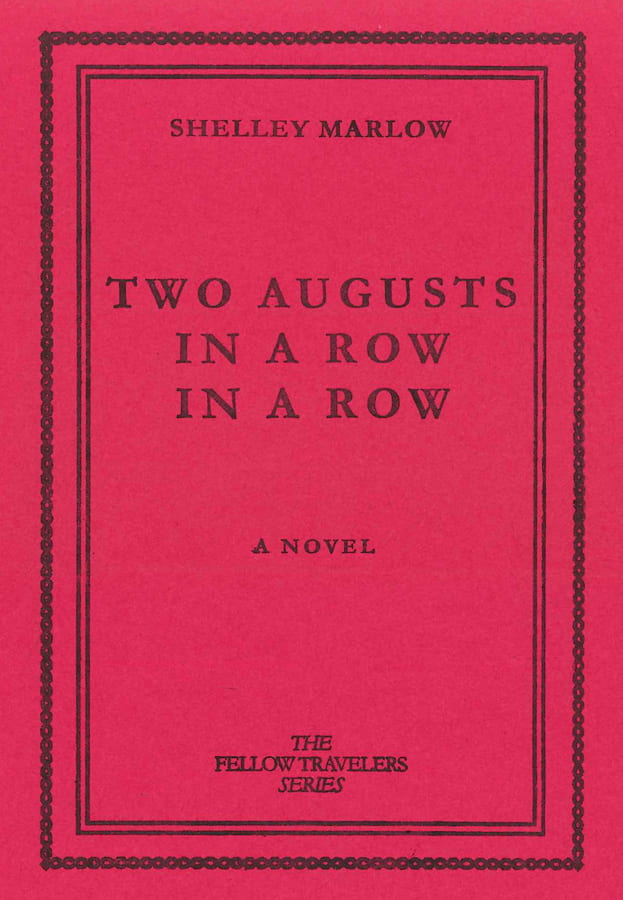

There are all kinds of ways in which a book’s form can intensify its content, draw its words into relationships, inscribe its title within the family trees of works written by other people in other places and times. Books from the Fellow Travelers series started in 2012 by Publication Studio have exactly that effect from the very moment you look them in the cover: they are unmistakable descendants of works published fifty years earlier by Maurice Girodias at his Olympia Press, what he called its Traveller’s Companion series.

Through visual affinities, a lineage can be built, a history can be told, through bringing books together that look alike a pattern emerges not unlike the experience of spending time browsing Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, where images of similar gestures bespeak shared values, shared experiences.

Founded in 1953 from a desk in the back of the Rue Jacob bookshop in Paris, Girodias aimed to provide English-speaking soldiers abroad a complement to the already popular ‘Black Book’ series of detective fiction. But Olympia Press would scratch a different itch. Its name, after Edouard Manet’s infamous Olympia, is as evocative as gets: the first books in the series were erotic with no respect for the boundaries between high and low culture. Girodias collaborated with a collective of young ex-pats who moved to Paris as a kind of second-wave Lost Generation coalescing around a literary magazine called Merlin. At their insistence he published Samuel Beckett’s novel Molloy alongside Marquis de Sade’s La Philosophie dans le Boudoir, Apollinare’s Memoirs d’un Jeaune Don Juan, and George Bataille’s L’Histoire de l’Oeil, and Henry Miller’s Plexus. Over the years, money was so short that the Merlin collective would meet, drink, and invent smutty titles they had not yet written, sending out false catalogues to their subscribers, as John de St. Jorre describes in The Good Ship Venus: The Erotic Voyage of the Olympia Press (1984). The money made from pre-ordered books paid the authors to begin writing them.

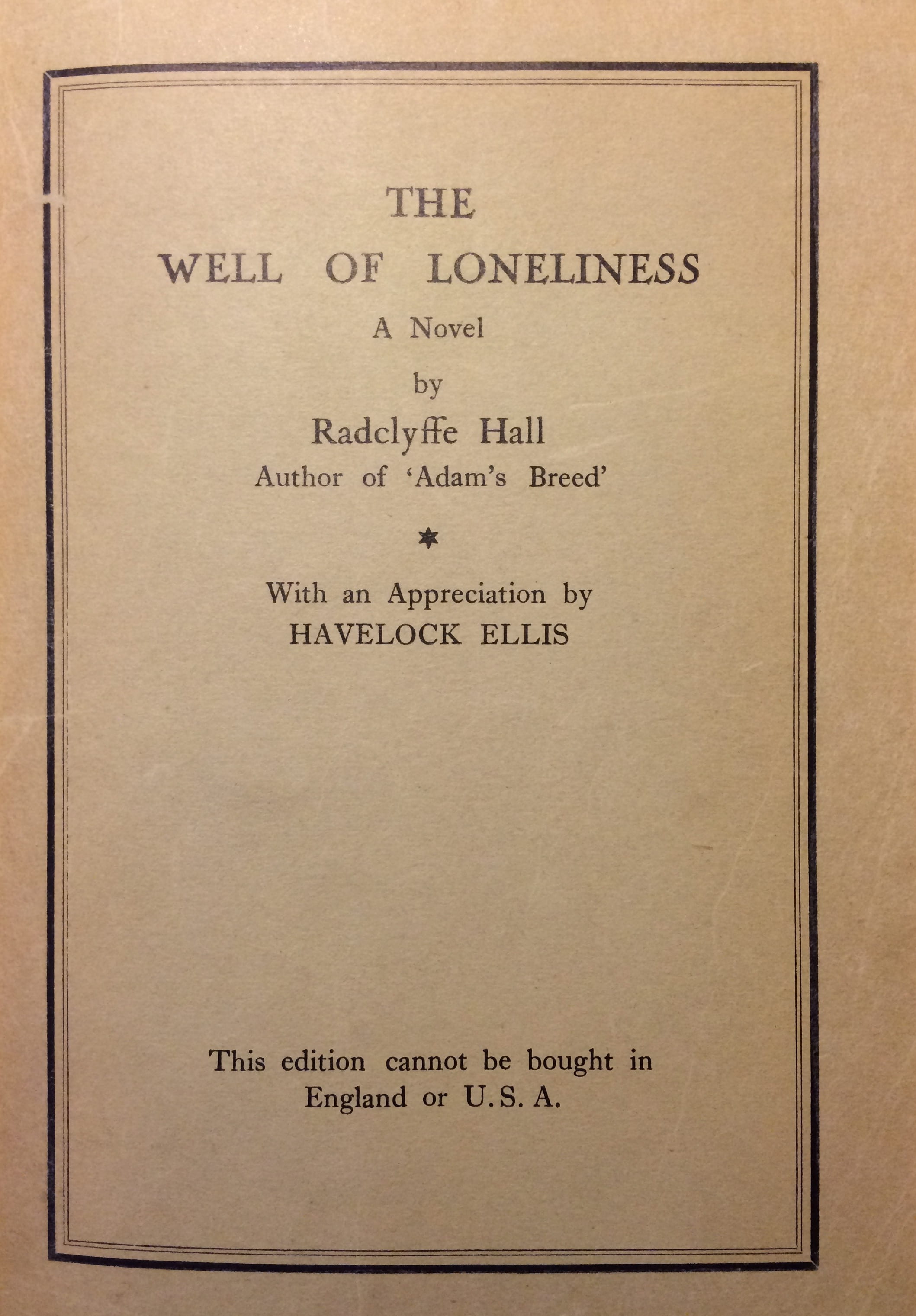

The books of Olympia Press were not the first to use the design. Girodias adapted it in homage to his father, the publisher Jack Kahane. Kahane ran Obelisk Press and had a whole history of his own in the shoestring publishing industry, and he was no stranger to obscenity. Obelisk Press published Radclyffe Hall’s Well of Loneliness in 1933, Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer in 1934, and Anaïs Nin’s House of Incest in 1936. Girodias had rebellious literary taste coded into his genes.

“Fans were as fascinated by the ugly plain green covers as the addict by the white powder, however deceptive both may prove to be,” Girodias wrote about the appeal of his own series. Deceptive, too, is the view of any of these books in isolation, not only as it goes against the reality of addiction and addictive reading, but also because bringing each green book among its companions recreates a sense of the wide, wide world of effort it takes to shift values and tastes. At Olympia Press, there was a rotating cast of contributors and collaborators, men and women: Alexander Trocchi, George Bataille, Bataille’s wife Diane, Iris Owens, Marilyn Meeske. Helen and Desire, White Thighs and The Whip Angels, were all part of the literary ecosystem that made possible, intellectually and financially, works like Lolita, and Naked Lunch, now canonized, set apart.

“Fans were as fascinated by the ugly plain green covers as the addict by the white powder, however deceptive both may prove to be,” Girodias wrote about the appeal of his own series. Deceptive, too, is the view of any of these books in isolation, not only as it goes against the reality of addiction and addictive reading, but also because bringing each green book among its companions recreates a sense of the wide, wide world of effort it takes to shift values and tastes. At Olympia Press, there was a rotating cast of contributors and collaborators, men and women: Alexander Trocchi, George Bataille, Bataille’s wife Diane, Iris Owens, Marilyn Meeske. Helen and Desire, White Thighs and The Whip Angels, were all part of the literary ecosystem that made possible, intellectually and financially, works like Lolita, and Naked Lunch, now canonized, set apart.

From visual affinities, to the bonds of blood, to the realities of fighting censorship through collaboration, the efforts of publisher-printers like Kahane and Girodias can be traced back and back. But they can also be seen to gain increasing vividness — and coherence — as they are lifted from the past and taken forward. The sparse covers of Kahane’s and Girodias’s books alongside those of Publication Studios name censorship as a common enemy of publishers. In Girodias’s case, Olympia Press opposed the censorship of obscenity laws; more recently, Publication Studios rejects the censorship that lies at the heart of a market that refuses to engage fresh talent in favor of predictable moneymakers. The constraints amount to the same thing: very similar groups of authors are left out, very similar types of writing are hard to find. Each Fellow Traveler (there are eight and counting) includes a Publisher’s Forward, which addresses the problem head-on:

Patricia No and Antonia Pinter’s battle cry gives new life to Maurice Girodias’s goals with Olympia Press, it gives coherence to his impact on the publishing landscape of the 50s and 60s, an impact that would have been difficult to assess at the time given his movements between Paris and New York, the constant legal and financial struggles. “We proudly present great work that the market has not endorsed, but that we believe in,” No and Stadler write. Their approach to updating the Traveller’s Companion to the Fellow Traveler’s series distills Girodias’s literary tastes into a modern manifesto against greedy publishing. Which is incredibly generous to Girodias, since he spoke as much about profit as love of good writing, and who did not always treat his authors well. He was a ‘toad’ to Valerie Solanas, and Breanne Fahs’ biography of Solanas painstakingly describes the conditions under which he held copyright of her S.C.U.M. Manifesto that pushed Solanas’s mental health struggles to breaking point. Girodias claimed she came to his office June 3, 1968 looking for him with a gun. He was out of town, so she went and found Andy Warhol instead. It’s unclear whether Girodias made this up to sell more copies of S.C.U.M. that he published immediately after the Warhol shooting made front-page news. Either way, Solanas’s fixation and despair over her treatment was a source of stress and debilitating paranoia she spoke of until her death in 1988. Publishing on the edge implies a certain kind of living on the edge, which does not necessarily imply kindness and fair treatment. Exploitation, however, can be dropped from the history that is kept alive, it can be re-written even if it is not done so by self proclaimed victors.

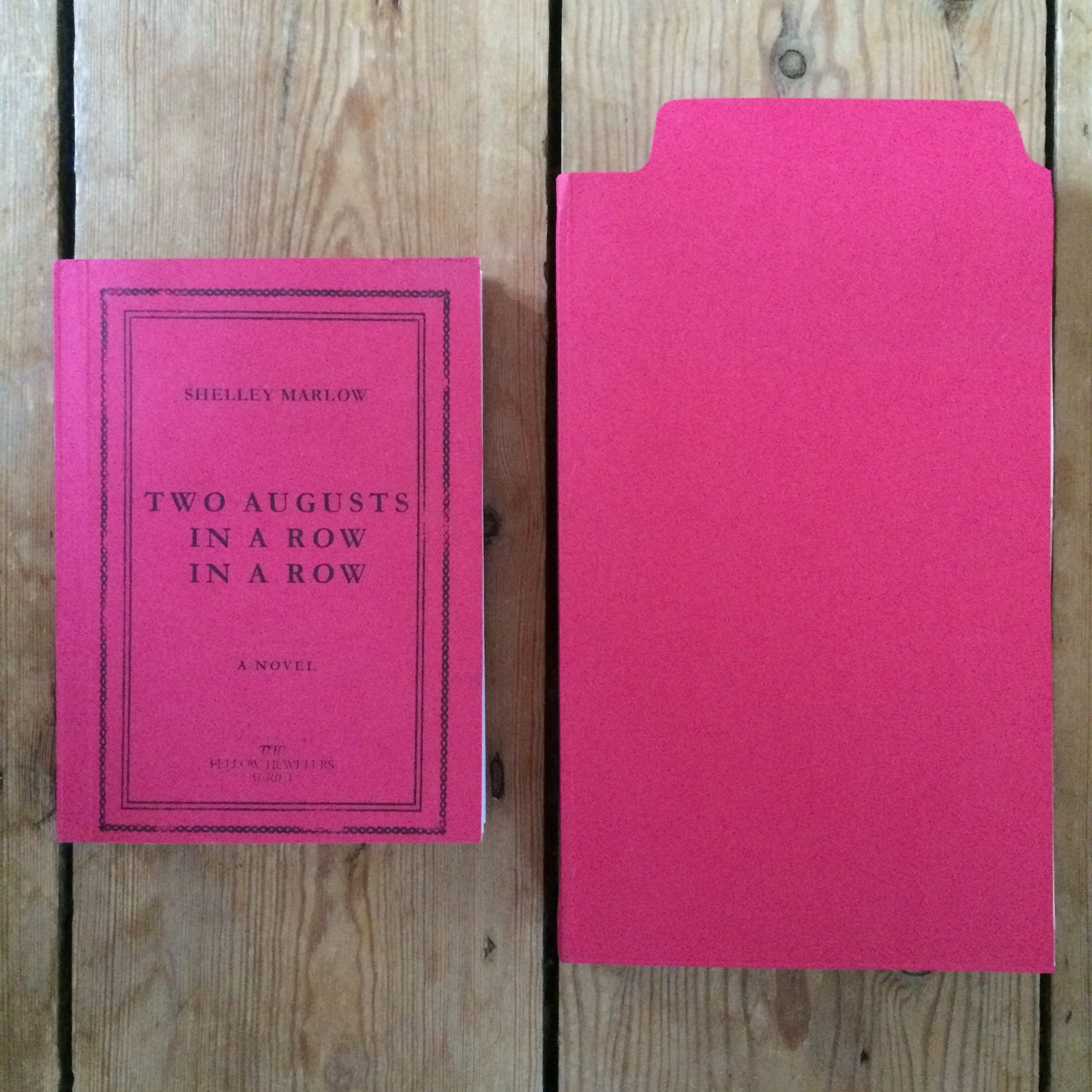

With Publication Studio, the struggle against market censorship goes even deeper, beyond the cover, to the ways in which the books themselves are assembled. Stadler and No are able to produce around 50 or 60 books per day through their Print on Demand system consisting of a black and white printer, a machine that puts glue on the spines, and a perfect binder: “Every day is different. That’s part of why we stamp date of production on the spine of every book.” Stadler said in an interview. The books are bound in file folders: “[B]ecause we were broke. You can get them free.”

Moreover, the methods travel well: the original Publication Studio was set up in Portland, Oregon, but satellite publishers using similar POD technology have cropped up all over the USA, and Canada, with one of the most recent incarnation opening up across the ocean in London, run by Louisa Bailey of Luminous Books.

Where big publishing houses pay little attention to transgressive authors, and POD produces incredibly messy results, the emerging constellation of Publication Studios addresses the shortcomings of both through ethical, well-made books printed on demand that showcase novels with a transgressive or political edge, including queer authors like Shelley Marlow and STS. There is an emotionally rich collapse of space between the roles of publisher-printers of the past, who staked their livelihoods alongside their authors in the works they published, and the work of publishers who remain active interpreters of the traditions they have chosen to inherit.

Adapted from part of a lecture delivered at the launch of Shelley Marlow’s Two Augusts in a Row in a Row at the London Centre for Book Arts, 29 October 2015. Correction (11/20): The co-founder of publication studio is named Matthew Stadler, not Mark. Publication Studio’s first location in Portland, Oregon is now run by Patricia No and Antonia Pinter.

November 17, 2015 at 8:44 pm

Brooke, I *love* this! I wrote my first-ever research paper about Olympia Press, when I was 15–it’s delightful that the distinctive cover design not only lives on, but also has been queered (“Fellow Travellers” describes a rather different notion of gender and sexual relations, I think, to “Traveller’s Companion”). Thanks so much for this great post!

November 20, 2015 at 3:10 am

I’m glad you enjoyed it Emily — and *definitely* check out “Two Augusts in a Row in a Row”, it’s gloriously genderbending, it’s constantly on the move!