by contributing editor Erin McGuirl

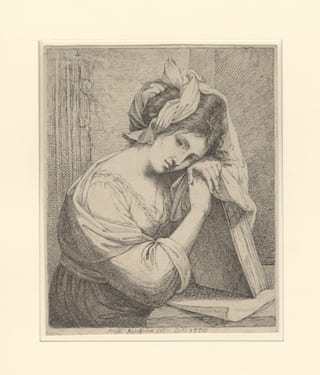

In an etched self-portrait dated 1770, Angelica Kauffman rests her weary head on a book propped up on her desk. In the early state of the print on display now at the New York Public Library, her melancholic gaze skims the top of the viewer’s head, just missing the eye. With her hair disheveled, in unadorned, simple clothes, she appears to us following a long day of hard work. The column behind lends an air of professionalism to the piece, abstractly situating her, if not indoors in a workshop, then in an urban environment. A founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, Kauffman was a highly skilled artist and a portraitist with a long, star-studded list of international clients. In this portrait, she is an artisan with work to do. In a later state held by Royal Academy of Arts, she has a different attitude. The column behind her is a tree, and her gaze meets our eye, now a bit softer. In this natural setting she is both an artist and muse, an inspiring force of creation and a creator, herself. In the early state, we see Kauffman the craftsman; in the later, Kauffman the artist.

Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807), Self-portrait, 1770. Early state from the The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library.

These subtle changes present contrasting views of the artist as both highly skilled artisan or tradesperson and as inspired creator of forms and images. They are especially apt representations of the many women artists whose work is on display in the fine exhibition now on view at the New York Public Library, Printing Women: Three Centuries of Female Printmakers, 1579-1900.

About fifty prints on display represent a huge range of styles, media, and abilities. A charming engraved doodle by an amateur, Sophie of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (1778–1835), is a marvelous picture of the beginner’s art. The forms of are flatly rendered with none of the variation in line and tone that more confident hobbyist-artists like Madame de Pompadour or Anna Maria von Schurman demonstrate in their more practiced work. Her lettering is crude and we see her literally practicing her abc’s between sketches of a large, stiff matron and a dainty young lady. Lettering was particularly difficult because it is necessary to incise text backwards on the plate, so that the print would be right-reading. What’s interesting here is that some of her sketches, particularly a gentleman in cravat and bicorne hat, show some practice at drawing. Shading on his lower right cheek and a white patch on the tip of his nose gives form to the outline of the head, suggesting three-dimensionality and practice (perhaps even instruction) in drawing. The print shows an individual learning use a burin, digging lines into a metal plate, and trying to achieve in metal some of the effects she’s learned to employ on paper.

Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807), Self-portrait, 1770. Later state from the collections of the Royal Academy of London.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, Adélaide Allou executed two of the most sophisticated prints on display after drawings by Fragonard and Hubert Robert. Both pieces of were designed as frontispieces for books. While the show opens with a series of prints by women who practiced engraving as a sophisticated past-time, its inclusion of obscure artists like Allou demonstrate how women printmakers succeeded as technicians whose mastery of a particular printmaking technique (in Allou’s case, etching) qualified them to translate the work of established masters from one medium to another.

Adelaide Allou (active late 18th century), “Racolte di vedute dissegnate doppo natura in napoli da Roberti intagliate adelaida allou sc. 1771 [title plate]” 1771. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library.

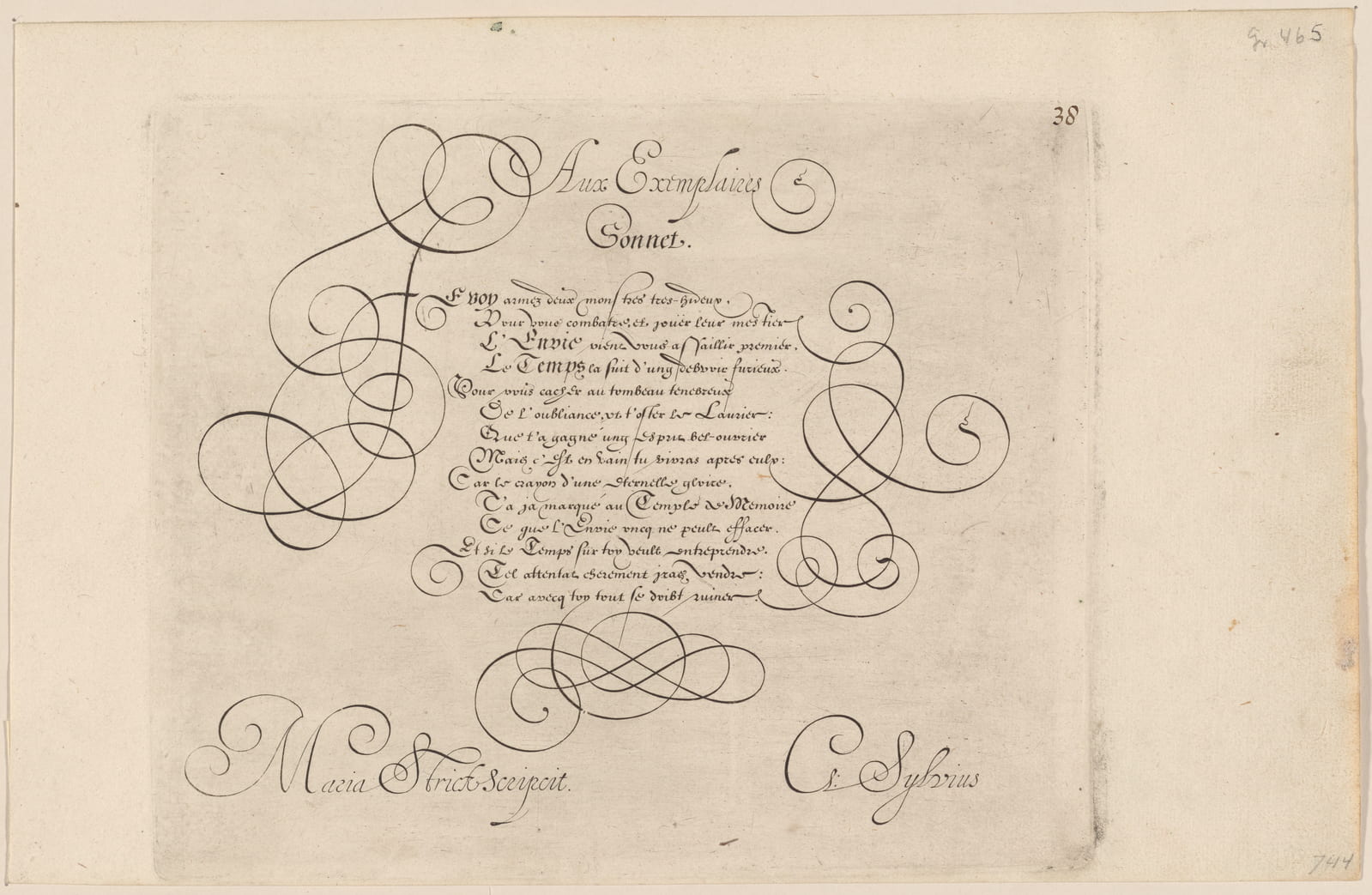

Maria Strick (b. 1577) “Aux Exemplaires. Sonnet” c. 1600-1699. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public.

Much of the art historical conversation around print culture in English revolves around reproduction, and the ways in which the multiplicity of images affects their meaning, value, reception, and consumption. The French, however, have a different approach. Scholars like Maxime Préaud, Marianne Grivel, and Corinne Le Bitouze have dug through the Archives Nationales to learn how the print trade actually worked, and they’ve discovered that the printmaking profession was mostly made up of semi-professionals with niche talents, who earned a living in a variety of ways as artisans. Unlike letterpress printing, which was a regulated trade, the French printmaker never needed to serve an apprenticeship or buy membership in a guild, and printmakers were free to find work as they pleased. For example, many artists in Women Printers learned to draw on metal from working printmakers. Madame de Pompadour studied under court painter François Boucher, who also occasionally worked as a printmaker.

Susanna Maria von Sandrart, 1658-1716. “Gabrielis Carola Patina” 1682. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library.

Many great print publishers kept their businesses in the family, and Printing Women shows several examples of work from women with relatives in the trade. Susanna Maria von Sandrart studied with her printmaker father, Jacob von Sandrart and her uncle, the painter Joachim von Sandrart. Exhibition labels often allude to friendships (and affairs!) that connect these women to broader circles of well known artists and intellectuals. Sandrart’s uncle Johann Georg Volkamer commissioned works by her. A print from the collection of Anne Claude, compte de Caylus, was reproduced in a drawing by Louise de Montigny le Dauceur. The print was etched and engraved by Augustin de Saint-Aubin. These relationships between women and a community of educated artists, scholars, and patrons pop up all over Women Printers, suggesting that there is a social-intellectual element to their stories that has yet to be explored, one that might look a lot like the communities that book historians have traced around the printers and publishers of texts in the early modern period.

Much like figures who appear at the fringes of early modern intellectual culture, so many artists in Printing Women deserve full length studies as individuals. The lack of biographical details for the vast majority of these women artists is woefully conspicuous in the clearly well researched exhibition labels. Exhibitions like this one must lead us to question what we know about these women, and the communities in which they lived and worked. Were they paid? Were some of these women the hands behind the countless unsigned prints circulating as single sheets or in books? Perhaps one of Printing Women’s greatest accomplishments is in reminding us just how much we don’t know about them as individuals or as groups.

Sophie of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (1778-1835) “A sheet of sketches and studies …” 1795. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library.

The show, however, is not without flaws. Printing Women draws exclusively from NYPL’s renowned print collection, founded in 1900 with Samuel Putnam Avery’s donation of 17,775 etchings and lithographs by 978 artists. Avery’s gift is a treasury of information about women printmakers because it absorbed the collection of prints by women built by Henrietta Louise Koenen (1830-1881) from 1848 to 1861. While both the website and lavishly illustrated accompanying booklet stress Koenen as the genius behind the collection, the exhibition tells us almost nothing about who this woman was and how she went about acquiring a large (but unquantified) number of prints. What’s more frustrating is the fact that the Avery Collection is minimally represented online in NYPL’s Prints & Photographs Catalog and Digital Collections Gallery, and there is no way to locate prints made exclusively by women or collected by Koenen online. Access on site, however, is excellent, particularly with the Print Division’s File on Women Printers. The situation is a sad reminder of what has been lost with the Library’s shift to digital promotion of an amorphous library brand, instead of its world-class collections.

Printing Women marks the third exhibition of prints from Koener’s collection in over a century. The first was in 1901 at the Grolier Club (the catalog they published is an invaluable resource), the second in 1973 at NYPL. The world has changed a lot since then, and despite the fact that digital tools have changed the ways that the world does research, the situation on the ground is much the same as it was in 1901. To uncover the stories of these women, we must look at the prints they made in their great variety and multiplicity, study our predecessors accounts of them, and most of all, we must visit Libraries and look at their collections. As Angelica Kauffman so artfully reminds us, prints change from impression to impression, there’s quite a lot to understand when we start to look carefully.

The exhibit Printing Women: Three Centuries of Female Printmakers, 1579-1900 runs at the New York Public Library until January 31, 2016.

December 2, 2015 at 1:22 pm

For readers interested in the French studies of engravers and rolling press printing (and printers) that I alluded to in my review, here is a brief bibliography of key sources.

Gaskell, Roger. “Printing House and Engraving Shop: A Mysterious Collaboration.” The Book Collector 53 (2004): 213–51. Print.

http://www.rogergaskell.com/Gaskell%202004%20Printing%20House%20and%20Engraving%20Shop.pdf

Griffiths, Antony, and British Library. Prints for Books: Book Illustration in France, 1760-1800. London: British Library, 2004. Print. The Panizzi Lectures 2003.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Prints-Books-Illustration-1760-1800-Lectures/dp/0712348743

Grivel, Marianne. La Réglementation Du Travail Des Graveurs En France Au XVIème Siècle. Paris: Presses de l’Ecole normale supérieure. Print.

Grivel, Marianne. Le Commerce De L’estampe À Paris Au XVIIe Siècle. Genève: Librairie Droz, 1986. Print. Publications de l’École Pratique Des Hautes études, Paris. IVe Section : Sciences Historiques et Philogiques. VI : Histoire et Civilisation Du Livre 16.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/23016591

Le Bitouzé, Corinne. “Le Monde Parisien de L’estampe Au XVIIIe Siècle: Un Imprimeur En Taille-Douce: Simon Collin.” Nouvelles de l’estampe 116 (1991): 36–42. Print.

Le Bitouzé, Corinne. Le Commerce De L’estampe à Paris Dans La Première Moitié Du XVIIIe Siècle. N.p., 1986. Print.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/758890794

Preaud, Maxime. Dictionnaire Des Éditeurs D’estampes à Paris Sous l’Ancien Régime. Paris: Promodis : Editions du Cercle de la Librairie, 1987. Print.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/18410701

Preaud, Maxime. “La feuille à l’envers.” Poésie & calligraphie imprimée à Paris au XVIIe siècle : autour de La chartreuse de Pierre Perrin, poème imprimé par Pierre Moreau en 1647 / volume publié sous la direction d’Isabelle de Conihout et Frédéric Gabriel ; préface, Henri-Jean Martin ; avec des études d’Isabelle de Conihout … [et al.]. Paris: Bibliotheque Mazarine Editions Comp’act, 2004. 133–137. Print.

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/55236938

Preaud, Maxime. “Les arts de l’estampe en France au xviie siècle : panorama sur trente ans de recherches.” Perspective: Actualité en l’histoire de l’art 3, 2009. Web. https://perspective.revues.org/1308?lang=en