by contributing editor Jake Purcell

I share with JHI Blog editor John Raimo a buzzing affection for philology. On the one hand, it’s a tool I feel I need desperately, helping me to tease out how such fickle things as words might be clumped together into sentences. But philology is also a joy: Thinking philologically lets the historian play with words, and to watch others at play.

But it can be challenging, as a historian of institutions, to find ways also of being a philologist. For one, I feel my amateurism very keenly. I have read articles on the different sounds that people alive in Merovingian Gaul (France-ish, c. 450-751) might have meant when they wrote the letter “a;” I have learned my morphological and syntactical shifts from Late to Medieval Latin; I have devoured everything I can find by Roberta Frank; but is it ever enough? Lest reading continue to serve as a substitute for action, I want to strain some of these underdeveloped muscles of philological practice by looking for some of the sensuality in the medieval legal documents that I work with. In particular, what can focusing on the sensuous reveal about evidence, proof, and facts—about how governments sort information into units that are judged to be “false,” and so ineffectual, or “true,” and so actionable?

The sensual philology that I mean is Martin Foys‘, born of the now-expanding list of things that philology can do. Sensual philology sidles up next to New Philology’s earlier interest in the materiality of the text and urges a more ecumenical attention to the relationship between media, words, and bodies, and also the physical world of senses and silences beyond the visual, including non-linguistic systems of communication. Foys’ insights and methodologies don’t seem unique to the relationship between words and sensation, but the stakes of this intersection are uniquely high. Susan Kus, an archaeologist of Madagascar, has pointed out that semiotics is insufficient for understanding things like proverbs, which rely on routine physical experiences for context. The sensory is given meaning beyond the physical experience of the body, and words are embodied with content that is not just intellectual, but physical and affective.

It is easy to see how a reading attentive to the affective and sensory (especially non-visual senses) tenor of a text can be rewarding in passages like this one, from the medieval Welsh tales collectively called The Mabinogion:

His arms were round her neck, and they were sitting cheek to cheek, but what with the hounds straining at their leashes, and the edges of the shields banging together and the spear shafts rubbing together and the stamping and whinnying of the horses the emperor woke up.

Constellations of love-inflected sensory experiences, indeed. Outside of dreams, historians have found plenty of bodily and sensual experiences within and adjacent to medieval institutions. But in the legal documents that I work with on a daily basis? What is their sensuality?

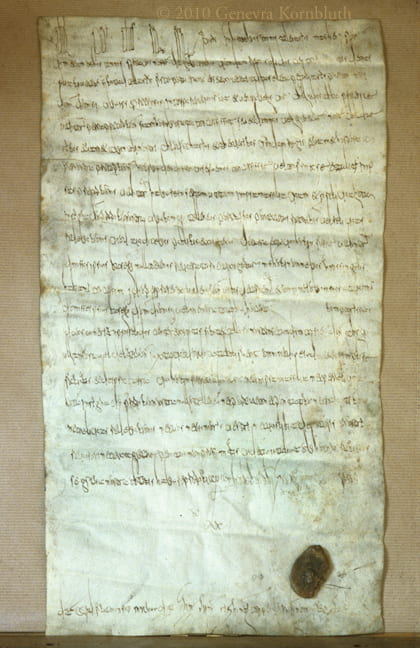

Copyright Genevra Kornbluth. This charter, Archives National K 3 No. 18, is near-contemporaneous with the placitum I discuss. It was written for another Merovingian king, King Chilperic II, on or around March 5, 716. There are at least two things that are remarkable about this particular text. One is that its royal seal is still attached, after 1300 years. Another is that it is written on parchment, a sign of the document’s relative youth. Papyrus, not parchment, was probably the Merovingian chancery’s preferred substrate for legal documents until the end of the seventh century.

Here is a near-translation of most of a Merovingian placitum (a formula-based, post facto record of a dispute resolution adjudication, but also the word refers to the adjudication process itself and also means pleasing or agreeable):

Theuderic, king of the Franks, to the noble men.

One day, we, in the name of God, were seated at our palace at Ponthion along with our retainers so that we could hear everyone’s cases and judge lawful legal proceedings. Representatives of the church of our special protector the blessed martyr Dionysus (where he rests bodily and where the saintly man Abbot Godobald is seen to preside) came to us here and spoke out against the noble man Ermente. They said against him that he had given some of his land called Boran- sur-Oise on the river Isère in the region around Chambli, which he came by for himself legally through his father Nordbert and his brother Gunthechar, both dead. to the venerable man the abbot Godobald for the church of the lord Dionysisus. He had given and confirmed the gift through a deed of sale, and he showed the document to those assembled for reading. When it was read, and while that Ermente was among those present, it was asked of him by our nobles if he had sold that land Boran-sur-Oise of his to that Abbot Godobald for the church of St. Denis, and if he had taken the purchase price for it. Ermente said to those present that he sold to the Abbot Gondobald for the church of his lord St. Denis that land of his in the aforesaid place Boran-sur-Oise in the recently mentioned Chabliois and asked it to be confirmed and received the purchase price according to his satisfaction, and had asked to confirm the sale. For that reason we together with our nobles agreed to decide that, as the noble man Cumrodobald, our count of the palace, testified how the case had been investigated and completed, we ordered that the aforementioned representatives of the venerable man the Abbot Godobald and of the church of his lord Dionysius for their part hold for all time, inviolably and with all rights that same property of Boran-sur-Oise in the abovewritten Chabliois…, with their charters having been looked over…

Many things are confusing about this document: Where is the conflict? Why is text that is standard for a deed of gift spliced onto the end of a judgment formula? I want to leave those aside to point out that, as a group, the Merovingian placita are very loud. People are always speaking, interrupting, claiming, stating, responding, agreeing, promising, asking, asserting, contradicting, professing, testifying, relating, determining, swearing, reading aloud, requesting, interrogating, ordering, declaring, and pledging. Because of all this noise, or maybe in spite of it, people were also doing a lot of hearing; the placita are peppered with curious assurances that this was the case, or that there were people around to hear all this noise.

The impulse to explain in detail seeing and hearing is symptomatic of a larger epistemological habit of Merovingian diplomas: their effort to convey precisely how information was sent and received, especially information related to critical pieces of evidence. Medieval legal writing loved rhetorical specificity (“that land of his in the aforesaid place Boran-sur-Oise in the recently mentioned Chabliois”), and that specificity could manifest itself at different levels, including over the course of the whole placitum. Someone claims that a charter exists, it is made to appear physically for the purpose of reading aloud, it has been read aloud, it contained such and such information. The information is heard, it is confirmed by an official, taken to another official, written in the document, then confirmed again. (This last part, of the process, notably absent from the placitum above, is often described in others, and also frequently confirmed by notes in a Merovingian shorthand made on the documents.)

Getting information from one charter to another apparently required an odd alchemy, one that created a tangible link between the ink of the words on the page of the charter mentioned in the placitum, the ears of the king and court who made and recorded the decision, and the ink of this new placitum itself. Knowledge here is embedded in sensory experiences as a kind of physical movement. Seeing, hearing, and reading drag pieces of data from out of the secret interiors of people and documents into the open (Merovingian law always happens publice), where their truth can be verified or denied. But the careful nestling of source of information against source of information doesn’t stop here, at the decision; it extends all the way to the scribe, who is, after all, the one to record it. The carefully described passing of information from document to group to official to scribe to confirmer glues all of this information together into a coherent, sure narrative.

So, what does this shifting of perspective do for the legal or institutional historian? Most pressingly, it shows that Merovingian legal writers had assumptions that were different from those of the modern legal tradition about how writing worked as a technology, about what the law could do, and about how legal institutions made and preserved facts. The Merovingian placita offer a good opportunity to think about these issues: The placitum is probably a Merovingian genre. developed and use by Merovingian legal writers to meet the needs of Merovingian institutions. The documents are not transcripts, but recollections structured by formulas designed to elicit specific kinds of information.

A more traditional approach to this essay would have asked about categories of and rules for evidence – the relative efficacy of testimony versus written documents, or the place of oath-taking and the ordeal. Looking at the physical world of the placita shows how unsatisfying a Merovingian scribe might have found those sharply drawn categories. Facts were facts not because they could be isolated and examined individually, but because they could maneuver so lithely among texts and between text and speech, they could be read, spoken, and heard.

Leave a Reply