by contributing editor Erin McGuirl

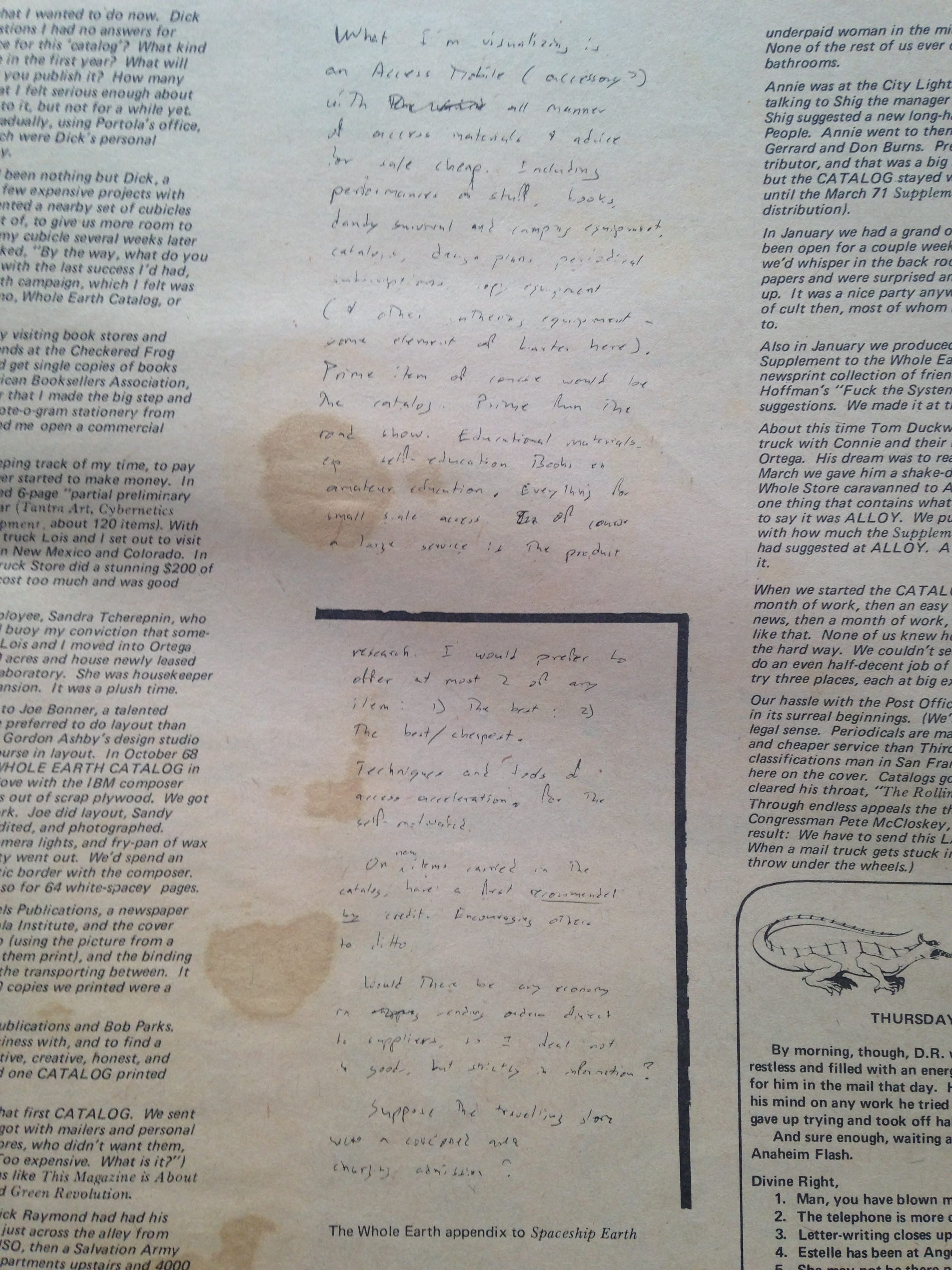

The endpages of Brand’s copy of Spaceship Earth, reproduced in the 1971 Last Updated Whole Earth Catalog and every catalog that followed (Reproduced from the author’s collection.)

The story of the Whole Earth Catalog begins with an annotation. During the flight home from his father’s funeral in March of 1968, Stewart Brand (b. 1938) covered the endpapers of the economist and writer Barbara Ward’s recently published Spaceship Earth with notes on how he hoped to help friends starting “their own civilizations hither and yon in the sticks.” What did he think his friends needed? Knowledge – how to raise goats, preserve summer fruit, build their own dwellings. And how was he going to get it to them? He was going to compile a bibliography and sell it, along with books and other tools, out of a truck. “Prime item of course,” he scrawled, “would be the catalog.”

Brand was a Stanford graduate, Army parachutist, a legal scientific experimenter with LSD, Merry Prankster, and a member of the media art collective USCO. In 1968 he was working for the Portola Institute, a one-year-old educational non-profit. During his first six months on the job it sounds like he put together a few failed projects (one was called E-I-E-I-O), visited bookstores, and read a lot. His major influences were Buckminster Fuller, cybernetics theorists Norman Weiner and Heinz von Foerster, and Marshall McLuhan.

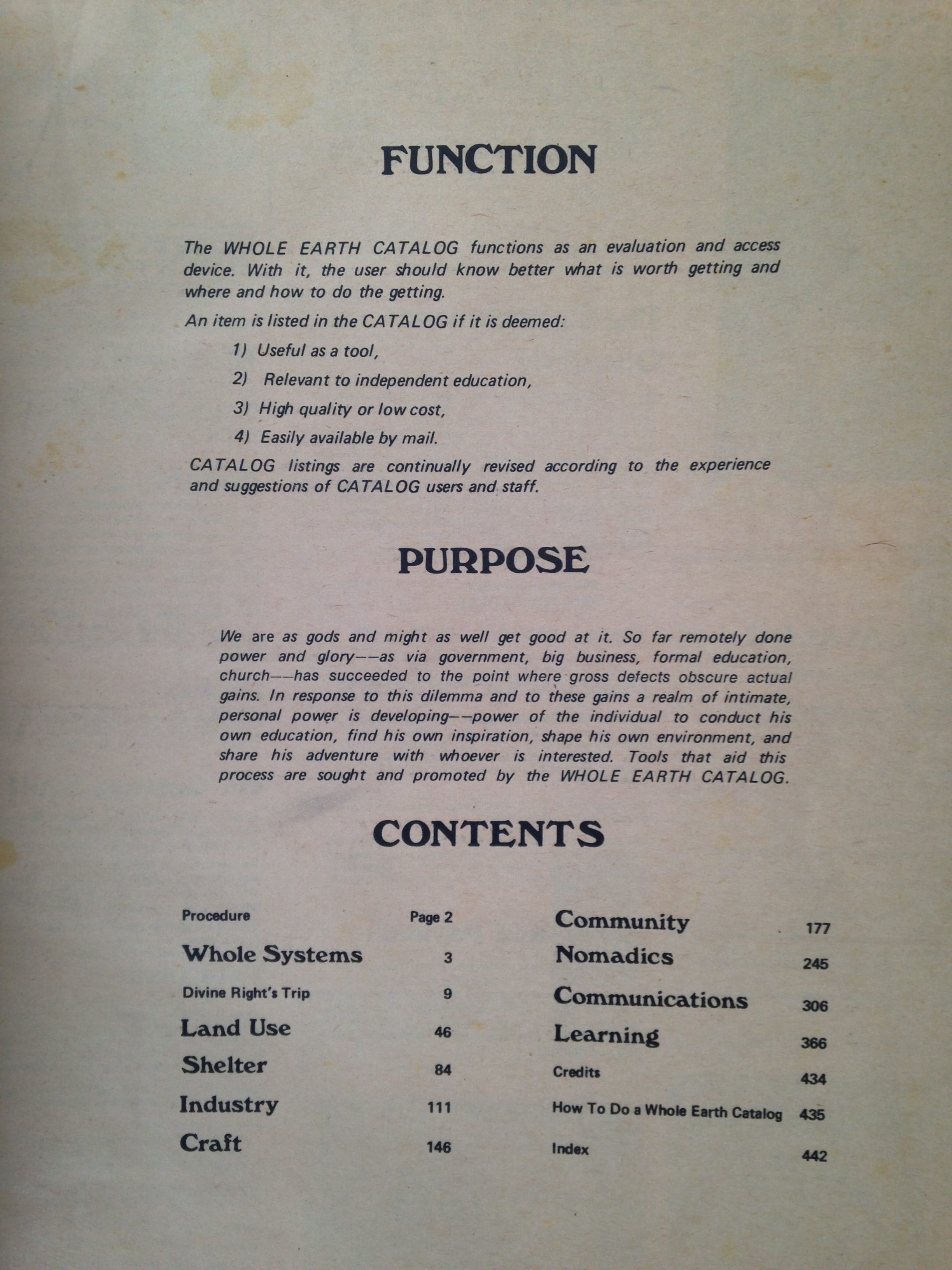

The first issue of Brand’s bibliography, the Whole Earth Catalog, appeared in the fall of 1968 and a revised and expanded catalog appeared annually, with supplements in January and March that included corrections, longer form articles, and reader correspondence. This is Brand’s description of the project, which appears inside the front cover of every Whole Earth Catalog:

Page 1 of the 1974 Last Updated Whole Earth Catalog. While the table of contents changed from issue to issue, the “Function” and “Purpose” statements always appeared as they did in the first issue in 1968. (Reproduced from the author’s collection.)

The catalog is an “evaluation and access device,” promoting tools that support the individual wishing to “conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, and share his adventure with whoever is interested.” Yet while the catalogs do list a lot of things that aren’t books –the fall ’69 issue lists a Jawa motorcycle, Craftsman bench vises, Royal Signet typewriters, the HP 9100A desk-top calculator/early computer, and a Curta calculator – bibliographical notices followed by brief book reviews fill up far more than half of its pages. From the beginning of the project, the book (or perhaps more aptly, the codex) was understood as a tool, a material object used for the storage and access of information.

Bibliographical notices in the Catalog consist of a short review printed in italics, complete bibliographical and ordering information in bold, excerpts printed in roman, sometimes including illustrations and almost always a picture of the book cover. In the early catalogs the reviews were Brand’s unless noted otherwise, and all were in the hip, casual style that characterized the underground press of the same period with a slightly more serious tone. His review of Dear Dr. Hippocrates by Eugene Schoenfeld (primary care physician to Hunter S. Thompson, Timothy Leary, and folk-rocker David Crosby, he also worked with Albert Schweitzer) reads as follows:

Long-hairs are doing new stuff with their bodies and nervous systems that occasionally needs medical attention or perspective. Communication was blocked, however, by the social understanding that they aren’t supposed to be doing that stuff. Dr. Schoenfeld and his medical advice column in the underground press cut through the blockage, and here came a spout of information as weird as it was useful. Good answers made the questions good. (WEC, 1970 p. 84)

And here is his review of Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition:

At the end of the peyote meeting, in the morning, food and water are brought in by a woman designated to be Peyote Woman. Indian women are not supposed to speak up much on general subjects, and during a meeting the women are silent participants. But at dawn Peyote Woman has the floor and the power. She speaks of fundamental things like water and birth and nourishment with all the authority of the Earth and with awesome perception.

Hannah Arendt does the same thing in this book. Her subject is the elements of the human condition. Her perspective, the threshold of travel away from the Earth.

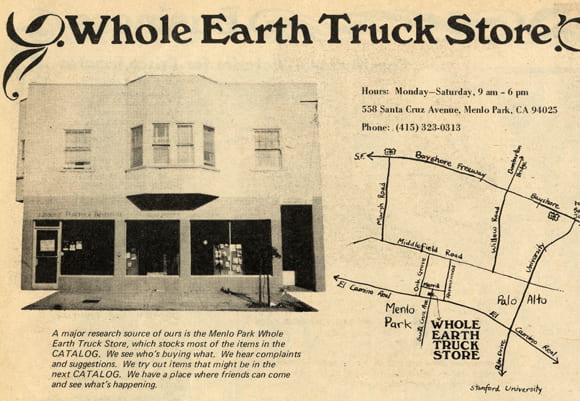

These two reviews do not resemble professional criticism, but they do speak to the huge range of coverage of the Whole Earth Catalog, which in turn represents the wide-ranging interests of hippie readers in the nineteen sixties and seventies. Schoenfeld’s book is a practical purchase for anyone experimenting with sex, drugs, and other (possibly risky) alternative lifestyle behaviors, especially “hither and yon in the sticks” where the nearest doctor might be in another county. Arendt’s book, on the other hand, is arguably useful to people trying to “build a new civilization.” The Whole Earth Catalog also listed ancient sources like the I Ching and the Kama Sutra, books that weren’t exactly unheard of but not always easy to obtain, particularly in suburban and rural America. By promoting goods that were easily accessible by mail and also operating a store in Menlo, CA, the Whole Earth Catalog evaluated and turned people on to a huge range of tools for thinking and living that had limited exposure in the mainstream media.

The Whole Earth Truck Store, so-called because the store first operated out of a truck that drove from commune to commune, selling books and other goods. (Reproduced from the author’s collection.)

The communal movements of the late sixties and seventies weren’t especially successful, and in that respect the Whole Earth Catalog wasn’t really, either. But the Catalog did succeed admirably both as a tool for accessing information and as an artifact of a cultural movement that was as curious about books and learning as it was about LSD and rock and roll. The Last Whole Earth Catalog was distributed by Random House and reached a larger number of readers than ever before. In 1972, the Catalog won a National Book Award (so did Flannery O’Connor and Allan Nevins) and sold 1.5 million copies nation-wide. In other words, in 1972, a million and a half people in America spent $5 (a relative value of $28.30 in 2014) on a bibliographical tool. In other words, in 1972 the National Book Foundation not only nominated but actually awarded a prize to a book that recommended Robert E. Brown’s Psychedelic Guide to Preparation of the Eucharist.

There’s a lot that can (and should) be said about this, but I’d like to focus squarely on the bibliographical and book historical implications of the Whole Earth Catalog’s success. As Brand’s annotations in Spaceship Earth show, the project was a bibliographical one from the very beginning. In the “How to Do a Whole Earth Catalog” chapter of the 1971 Catalog (it appeared in every updated Catalog thereafter) the first three sub-headings describe the Researching, Reviewing, and Editing processes in catalog production. Editorial work was serious, and there were strict standards for bibliographical description. The Supplement was published, in part, as an errata sheet, with updates and corrections to entries that had changed, or were incorrect in the previous catalog. On the next page he covers layout, and subsequent smaller articles cover book acquisitions, the business of starting running a truck store, with a thorough and honest article on the capitalization (a dirty word in the hippie dictionary) of the entire operation. It’s not so different from the kind of treatment that D.F. McKenzie gave to the Cambridge University Press in his pioneering bibliographical study of its history, published in 1966.

Brand also used books like a Winthrop, and arguably for the same reasons. As we’ve seen, he’s an annotator. His reviews and writing in the Catalogs constantly reference other books, sometimes with page numbers. Both wanted to build new civilizations in America, and made books their guides in that endeavor. The success of the Catalog, particularly in 1972 suggests that a whole lot of Americans could have been doing the same things with their books. Many readers went on to publish their own catalogs; in my collection I have copies of The First New England Catalog and Rainbook: Resources for Appropriate Technology. Both focus mostly on books but also list other types of tools, with a narrower range of focus than the Whole Earth Catalog. Both mimic the Catalog in bibliographic detail, and recommend a variety of tools that ranging from books to games to boats.

The Whole Earth Catalog is a rich record of American culture and civilization at one of the most complex and turbulent times in our history. Brand, and by extension, the Catalog’s community of readers, were sophisticated users of books: tools for information storage and access that had been in use for almost a millennium. Much like the Byron quoting coal miners in Jonathan Rose’s Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes (p. 241), the creation and success of the Whole Earth Catalog shows just how integral books are in the lives of people across all walks of life.

3 Pingbacks