by contributing editor Brooke Palmieri

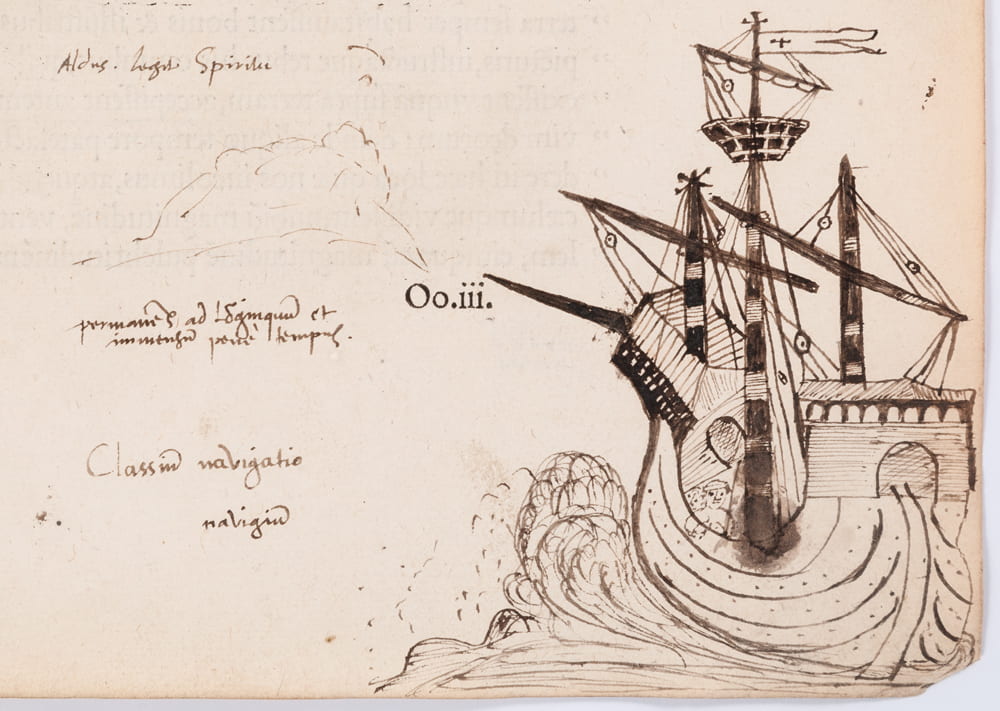

Dee’s doodle of a ship from vol. 2 of Cicero’s Opera omnia (Paris: Estienne, 1539 – 40). [CN10550] © RCP

“Bereave” was understood in the 16th century as an active verb: to take by force. It has languished since then into the passive, desolate state of those who survive what they have lost. Bereaved of his books, and later his estate at Mortlake, and his livelihood after James I had ascended the throne, John Dee’s failures have mellowed him out over the years. He has become something of a loveable victim that deserves respect for the sheer breadth of his studies: mathematics, alchemy, medicine, astrology, astronomy, cryptography, theology, law.

That legacy has extended to the ways in which Dee’s emotional gaps are filled with literary sources. When Dee is linked to Shakespeare’s Prospero, he is Prospero the victim, Prospero as he appears to his daughter Miranda, who admits to “neglecting worldly ends” for love of books, Prospero as he was betrayed by those more at home in the court than the library. He has not been linked with the Prospero who forces Miranda to sleep when he doesn’t want her to know what he’s up to, who threatens the spirit Ariel with slavery, who torments Caliban, or uses his magic to forgo politics and regain his kingdom at any cost. Caliban alone offers an alternative perspective, and it all comes down to books. As Sherman points out, Caliban’s attempted to overthrow Prospero begins with attacking his library:

…Remember

First to possess his books, for without them

He’s but a sot, as I am, nor hath not

One spirit to command — they all do hate him

As rootedly as I. Burn but his books. (Act 3, Scene ii)

This is not symbolic: burning Prospero’s books removes a threat of tyranny, depriving him of the means by which he has subjugated an island and conjured storms forceful enough to sink ships in its orbit. But to go further: Prospero’s quaint distinction between bookishness and worldliness collapses in Caliban’s description— the library becomes the throne-room.

To complete the circuit, consider applying Caliban’s description of that library to an understanding of the library of John Dee. Without a sense of the real stakes of possessing its contents, the story of Dee’s library makes no sense: not the nightmares, the pillaging, the bereavement, nor even the status of the library after his death. It was desired by statesmen and alchemists alike, from Robert Cotton (1570-1631) who even bought land around Dee’s house in 1609 in hopes of finding buried manuscripts there, to Elias Ashmole (1617-1692) who obsessively sought Dee’s books half a century later. To think for a moment like Caliban requires us to consider the darkest extremities of what it means to reconstitute Dee’s library; and maybe even for a moment, to be thankful that it does not survive in its entirety.

The first exhibition to bring together so many books in one room salvaged from Dee’s library confirms that. Scholar, Courtier, Magician: the lost library of John Dee at the Royal College of Physicians shows through its bibliography of books owned, or thought to be owned, by Dee that when combined, the scholar, the courtier, and the magician are each facets of Dee, the Imperialist, the first recorded person to coin the term ‘British Empire’. To see these books and instruments together in one place offers a viewpoint that complicates studies of Dee, and indeed any Renaissance aspirant to “universal” knowledge. Francis Yates in Theatre of the World portrays Dee’s library as “the whole Renaissance” — both typical in its ambitions and exemplary of its time. Deborah Harkness’s wonderful John Dee’s Conversations with Angels reconstructs Dee’s synthesis of all he knew into the search for a “universal science” that would “extend a ladder from the deteriorating world to the heavens.” But Scholar, Courtier, Magician forces us to ask: why did men like Dee want to know everything? As Jeremy Millar’s film commissioned for the exhibit shows: beware the know-it-all, whose knowledge amounts to a need to control. An English emblem book from 1586, Geoffrey Whitney’s Choice of Emblemes, tells us “usus libri non lectio prudentes facit”; it is the use of books, not the reading, which makes us wise. To think seriously about the way John Dee used, and aspired to use, his books produces some sinister kind of wisdom.

No wonder Dee could argue so forcefully in General and rare memorials pertayning to the perfect arte of navigation (1577), and his other works, for a British Empire: there are books in his library to engineer such a feat. Alchemical works in theory provided instructions to make the gold to fund voyages to foreign lands. Books on astronomy, astrology, mathematics, cartography, and navigation make it possible for those ships to efficiently plan and complete the journey. Histories provide tough lessons and useful strategies about subjugating the locals: predominantly works about the Roman Empire, but also the Ottoman Empire (Francesco Sansovino’s Gl’annali turcheschi), and more recently works on trade with the East (João de Barros’s L’Asia) and the conquest of the New World (André Thevet’s La cosmographie universelle and Cosmographie de Levant). Cross-reference these with Matthew Paris’s Flores historiarum on King Arthur’s mythical dominion, and the justification for a particularly British Empire is given “historical” precedent. Finally, use magic to contact the angels and support human agency with divine right. As the angel Murifri told Dee, recorded in his diary:

The Earth laboreth as sick, yea sick unto death.

The Waters pour forth weepings, and have not moister sufficient to quench their own sorrows.

the Aire withereth, for her heat is infected.

The Fire consumeth and is scalded with his own heat…

Hell itself is weary of Earth: For why? The son of Darknesse cometh now to challenge his right: and seeing all things prepared and provided, desireth to establish himself a kingdom; saying, “We are not stronge enough, Let us now bulid a kingdom upon earth, and Now establish that which we could not confirm above.”

It should be taken seriously that Dee the magician justified his use of magic as an arm of the state and in that way distinguished it from mere witchcraft. Dee’s angelic conversations cast the earth as an apocalyptic wasteland in need of saving. They were the final justification that in the face of decay, of Satan, of apocalypse, a unifying force, a godly empire, was necessary to put the world to rights. He was not alone: a miscellaneous manuscript in the British Library (Add MS 36674) shows the explorers John Davis and Sir Humphrey Gilbert contacting angels and visiting the otherworldly library of King Solomon to aid in their own voyages.

Claude Lorrain mirror in shark skin case, believed at one time to be John Dee’s scrying mirror. Published: – Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Credit: Science Museum, London.

Dee’s library, angels and all, amounts to a plan for that, with a full realisation about what would happen to those that may resist— hence his advocacy for a strong navy, his readings of military histories, his familiarity with Spanish and Portuguese expeditions. Look into the obsidian mirror that was allegedly Dee’s, originally taken from Mexico in the wake of Hernán Cortés, and the bloodshed involved in such a plan becomes not imagined but proved. At what cost did such a mirror cross the seas all the way to Dee’s house at Mortlake? A new spectral analysis of a 19th century portrait featured in the exhibition of Dee “performing an experiment” for Queen Elizabeth, painted by Glindoni, speaks to that mirror. Underneath the painting’s layer of red and green, grey and black, making up an unassuming flooring of court, Glindoni had originally placed Dee within a circle of skulls.

John Dee performing an experiment before Queen Elizabeth I. Oil painting by Henry Gillard Glindoni.Published: – Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

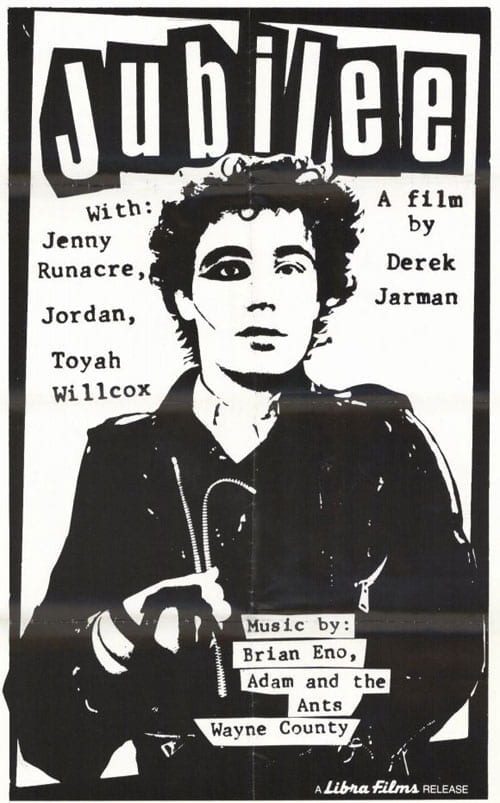

The impression left by Scholar, Courtier, Magician is perfectly (if not horrifically) complemented by Derek Jarman’s portrayal of Dee in Jubilee, who in a conflation with Prospero, conjures the spirit Ariel in order to time travel with Elizabeth I into London in 1978. “I will reveal to thee the shadow of this time,” Ariel promises; Dee and Elizabeth call it entertainment. They are transported into a violent and anarchic England that would have squared with the angel Murifri’s desolate depiction, with one crucial difference. It is a Britain run and driven to ruin by a central figure who controls the global market through his control of media and finance. In other words, a British Empire that spans the globe, of consolidated wealth and knowledge taken to exactly the extremity Dee himself hoped to engineer in his own time.

Scholar, Courtier, Magician: the lost library of John Dee is on view at the Royal College of Physicians in London until July 26, 2016.

4 Pingbacks