By guest contributor Barbara Heritage

Reading—how we read, what we read, and where we read—has attracted a great deal of attention during the last decade. From the pages of The New York Times to those of specialized scholarly journals, we find all kinds of attacks, defenses, statistics, insights, proposals, and agendas pertaining to the reading subject—often in connection to advances in digital technology and the legitimation crisis in the humanities. Amidst these conversations, the dual practices of reading and literary critique have been called into question within departments of English and comparative literature as academics (re)assess their engagement with hermeneutics. What does it mean, for instance, to conduct “close reading” as opposed to so-called “surface reading” or “distant reading”?

In 2014, literary theorist Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht went so far as to claim that “we quite literally do not know anymore, and do not know yet, what ‘reading’ exactly is for those whom we are teaching how to read” (101). In her recent study, The Limits of Critique, Rita Felski points to a similar failure: “Given the surge of interest in the questions of reading—close and distant, deep and surface—the neglect of the hermeneutic tradition in Anglo-American literary theory is a little short of scandalous” (33). Drawing upon her own teaching experiences, Felski writes: “What else could we teach our students besides critical reading? The bemusement likely to greet such a question speaks to the entrenched nature of a scholarly habitus […] yet there comes a point when many [students]—especially those who do not see themselves as professors in the making—turn away. They do so, I believe, not because of any inherent distaste for theory but because the theories they encounter are so excruciatingly tongue-tied about why literary texts matter” (“After Suspicion,” Profession 8, 29–30).

Looking to identify alternative interpretative methods for understanding the history of reading, greater numbers of theorists seem to be engaging with the field of book history. Both Gumbrecht and Felski, for instance, have gestured to the scholarship of book historians Roger Chartier and Janice Radway, whose research seems to suggest fresh possibilities for inquiry into the way that reading practices have been shaped over time, and in various social circumstances. Yet bibliography—the sibling discipline of book history—has not fared so well in discussions about postcritical reading.

Bibliography, broadly conceived, is the study of the materials and processes involved in the production and transmission of “books,” whether they be manuscript, printed, or digital. The descriptive nature of bibliographical analysis would seem to suggest a viable alternative for those who seek different approaches for understanding the social lives of texts. (Indeed, one of the most widely read works of bibliographical scholarship is D. F. McKenzie’s Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts.) Yet the field tends to be overlooked, ignored, or misunderstood among theorists, in large part owing to a long-running rift between bibliography and literary interpretation that dates back to New Criticism.

In her widely read essay, “Close but not Deep: Literary Ethics and the Descriptive Turn,” theorist Heather Love rightly points out bibliography’s overall “disengagement with critical hermeneutics” (382). Although Love’s assessment is accurate, it is also one-sided—assuming that neither critical hermeneutics nor literary theory have any need to engage meaningfully with bibliography. Love’s critique thus continues to enact that same disengagement that it reproaches. Meanwhile, bibliographers themselves have, in the past, been more than disengaged from literary criticism—some have been openly hostile toward it. In 1957, Fredson Bowers began his Sandars Lectures (later published as Textual & Literary Criticism by Cambridge University Press in 1966), as follows: “The relation of bibliographical and textual investigation to literary criticism is a thorny subject, not from the point of view of bibliography but from the point of view of literary criticism” (1). This mutual antagonism persisted through the 1970s until the early 80s, when Jerome McGann and D. F. McKenzie each worked, with some success, toward establishing a rapprochement between the two. Meanwhile, Terry Belanger established Rare Book School at Columbia University, and there was the founding of the Society for Textual Scholarship, followed a decade later by the founding of the Society for the History of Authorship, Reading, and Publishing, which formed in 1991. More recently, in 2012 and with funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Rare Book School’s current director, Michael F. Suarez, S.J., began developing critical bibliography so as to combine hermeneutic and bibliographical methods.

Much progress continues to be made in these areas. Yet the gap between bibliography and critique threatens to persist. If we return to the same article cited above, Love characterizes analytical bibliography and studies on book production, distribution, and consumption as “new methods” or “new sociologies of literature” that “distance themselves from texts and from practices of reading altogether” (373). Such practices, according to Love, “rely on a complete renunciation of the text (to focus, for instance, on books as objects or commodities)” (375). Bibliographers, according to Love, do not engage at all with the written content of the books that they study. This would, I believe, reflect a mainstream view of bibliography still held by many academics. For this reason, we should take a closer look at Love’s analysis.

First, some attention to historiography is needed. Practiced throughout the twentieth century, analytical bibliography is by no means a “new method,” nor has it ever been disconnected from textual criticism. Indeed, bibliography was practiced throughout the twentieth century chiefly in service of scholarly textual editing.

Because Love’s study neglects the history of bibliography as it has developed over the long term, her analysis merely reinscribes those same divisions that book historians and bibliographers have worked so sedulously to overcome. This calls attention to a second, and perhaps more important, point: clearly, “the text” that Love is describing has been conceived of as something very much apart from what bibliographers and textual editors study. How can those who work within the same discipline (English literature) hold such different opinions as to what constitutes a basic “text”? It’s my sense that, as a scholarly community, we cannot constructively proceed in our discussions of reading without exploring this question more closely together.

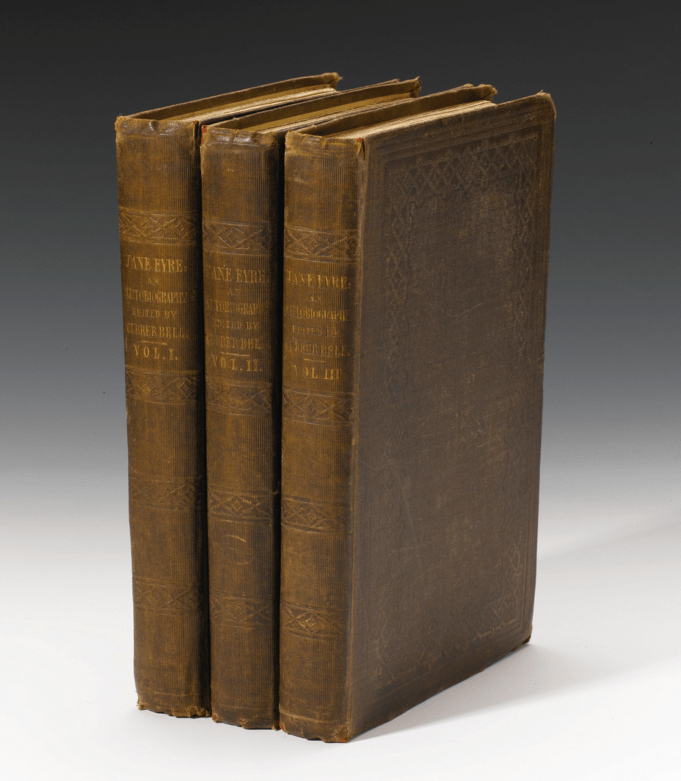

The 1847 Smith, Elder edition of Jane Eyre (Image from Sotheby’s)

Usually it seems to be the case that, when theorists speak of “the text,” they are indicating words alone, without reference to their textual condition—that “laced network of linguistic and bibliographical codes” (to borrow McGann’s phrase) that may, or may not, be shaped, to varying degrees, by author, publisher, printer, editor, bookbinder, or graphic designer. Most critics are less concerned with how a reader approaches, say, the Smith, Elder edition of Jane Eyre as opposed to the Penguin Jane Eyre, than they are with Jane’s narrative address to the reader. In contrast, bibliographers and textual editors speak of texts and, as needed, draw on their own terminology to specify the various versions that they encounter—for example, using specialized terms such as printing, issue, state, and variant. And so, to respond to Love’s point, bibliographers are actually very much concerned with reading practices—but with a focus on the actual, historical copies of books being read. For every “text” generally referred to by a theorist, a bibliographer finds versions of texts, whose contents and forms are always changing, inflecting our various readings of that work.

The question of what constitutes a “text” is not only central to critique; it is also becoming increasingly important as humanists and librarians alike reexamine the landscape of print and digital publication. How many versions of a work do we need for our teaching and research? If so, in what forms, and to what end? In the past, scholars working on the history of reading—Kate Flint, for example—have been more interested in the “rhetoric of reading practices” rather than the actual habits of readers (viz. The Woman Reader, 1837-1914, 73). Should we also be documenting and analyzing the markings made by common readers in books, as Andrew Stauffer, Kara McClurken, and others have begun to do with the University of Virginia’s “Book Traces” project—or as Erin Schreiner and Matthew Bright have accomplished with their City Readers project at the New York Society Library? Resources such as these would seem to provide hospitable bridges connecting both the teaching and research of those theorists, bibliographers, and book historians who contemplate reading practices. The reception of projects like these will certainly influence the future shape of our libraries and classrooms—and also possibly the nature of interpretation itself.

Barbara Heritage is the Associate Director and Curator of Collections at Rare Book School, University of Virginia. She serves as Secretary of the Bibliographical Society of America. She received her PhD in English literature after completing her dissertation, Brontë and the Bookmakers: Jane Eyre in the Nineteenth-Century Literary Marketplace.

March 1, 2016 at 4:00 pm

Not only do bibliographers dig through the multiple “versions of texts, whose contents and forms are always changing, inflecting our various readings of that work,” but we also seek out these forms in multiples copies. As a librarian, I hope to support and encourage new scholarship and critical inquiries in the humanities by building awareness of what the books in my collection – most of which can be sought out in other institutions, or via digital simulcra – have to offer. Teaching bibliography is a key way to introduce students, especially, to a research tool that will sharpen their critical faculties, and open doors not only into the lives of texts in print but also to the lives of book-workers (compositors, binders), book-owners, and readers through evidence that exists only in individual copies.