by contributing editor Erin McGuirl

“What is the I Ching?” was the title of Eliot Weinberger’s recent review of two new translations of the I Ching. It’s an excellent question, and in his review he expertly summarizes the history of the text, from its mysterious origins in the seventeenth century BCE through its introduction to European audiences in the eighteenth century, continuing into the height of the book’s popularity in the West in the mid-twentieth century. As he summarizes, the I Ching meant a lot of different things to a lot of different people, particularly in the West. Hegel thought it was a load of nonsense, Leibniz “enthusiastically found the universality of his binary system in the solid and broken lines,” and English sinologists like James Legge, Herbert Giles (both of whom translated the book) and Arthur Waley (who didn’t) were skeptical of its value as a philosophical text. In the 1950s and ’60s, artists, writers, and musicians, from Philip K. Dick to Bob Dylan to Merce Cunningham, found inspiration in the enigmatic poems they read in the Legge and Wilhelm translations. In the ’60s and early ’70s especially, the book appears all over the popular press. A search for “I Ching” or “Book of Changes” in a historical newspaper database turns up a trove of reviews of translations, interviews with artists and cultural figures, and editorials that mention the book in a variety of ways.

One can get lost in references to the I Ching in the popular press (truth be told, my research for this piece was so entertaining that it threatened to derail my writing completely). But I set out to find out what the I Ching meant to Mai-mai Sze. As JHIBlog readers well know, Sze is an enigmatic and fascinating woman whose dogged pursuit of knowledge across a wide range of subjects comes to life in the penciled notes she left in the vast collection that she bequeathed to the New York Society Library. One of very few traces of her scholarly life survives in William McGuire’s archive: a note at the bottom of a letter she sent him in 1979—thanking him for a copy of Iulian Shchutskii’s Researches on the I Ching—identifies her as a Bollingen author and “scholar of the I Ching” (Sze to William McGuire, 27 Sept. 1979. Box 47 Folder 9, William McGuire Papers, Library of Congress).

The index to her Tao of Painting—a translation of the Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, or Jieziyuan Huazhuan—lists thirteen references to the I Ching, and one is an extended passage covering several pages. In this section, forming a major part of her introduction to the text, Sze references the Legge translations in her footnotes. This is a bit odd, as the Wilhelm translation was available by 1950, in the midst of her work on the project.

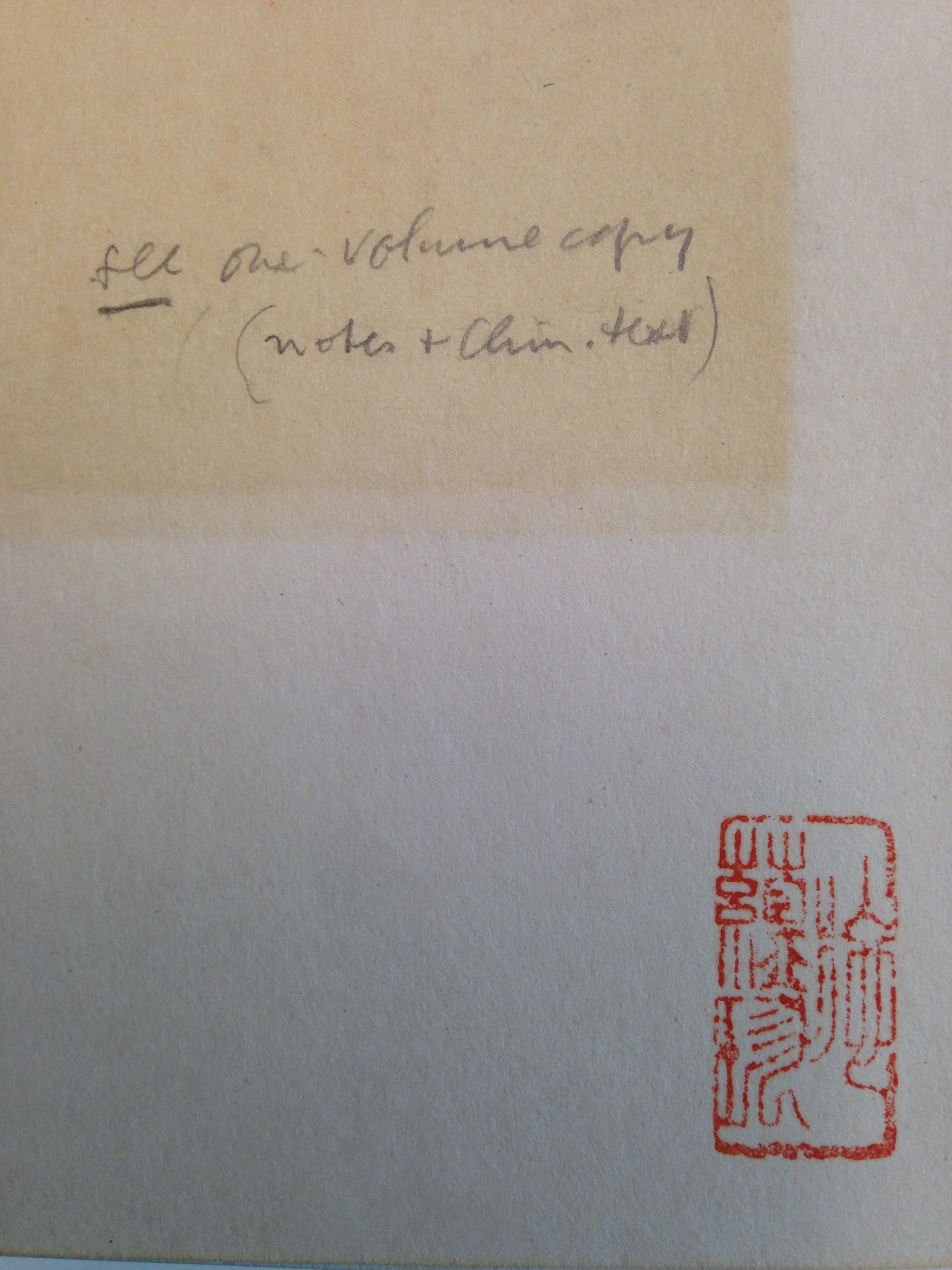

Although she does include an in-depth discussion of the I Ching and its relationship to Chinese painting in the introduction to the Tao of Painting (Bollingen, 1956), Sze seems to have turned to the I Ching in earnest quite late. A note on the title page of her copy of the two-volume set of the Baynes-Wilhelm I Ching directed me to her copy of the one-volume edition (which wasn’t published until 1968) for “notes + Chin. text.” Over a decade after the publication of the Tao of Painting, Sze studied the I Ching as closely as she studied other classics of Chinese philosophy (such as Laoze, the Confucian Analects, and the works of Mencius). I’m sad to report that her copy of the one volume Baynes-Wilhelm translation is now lost, leaving a gaping hole in the record of her interaction with this book. However, she did leave notes in the other translations that she owned, as well as in her copies of secondary sources on the I Ching in English. They reveal a bit about what she was up to.

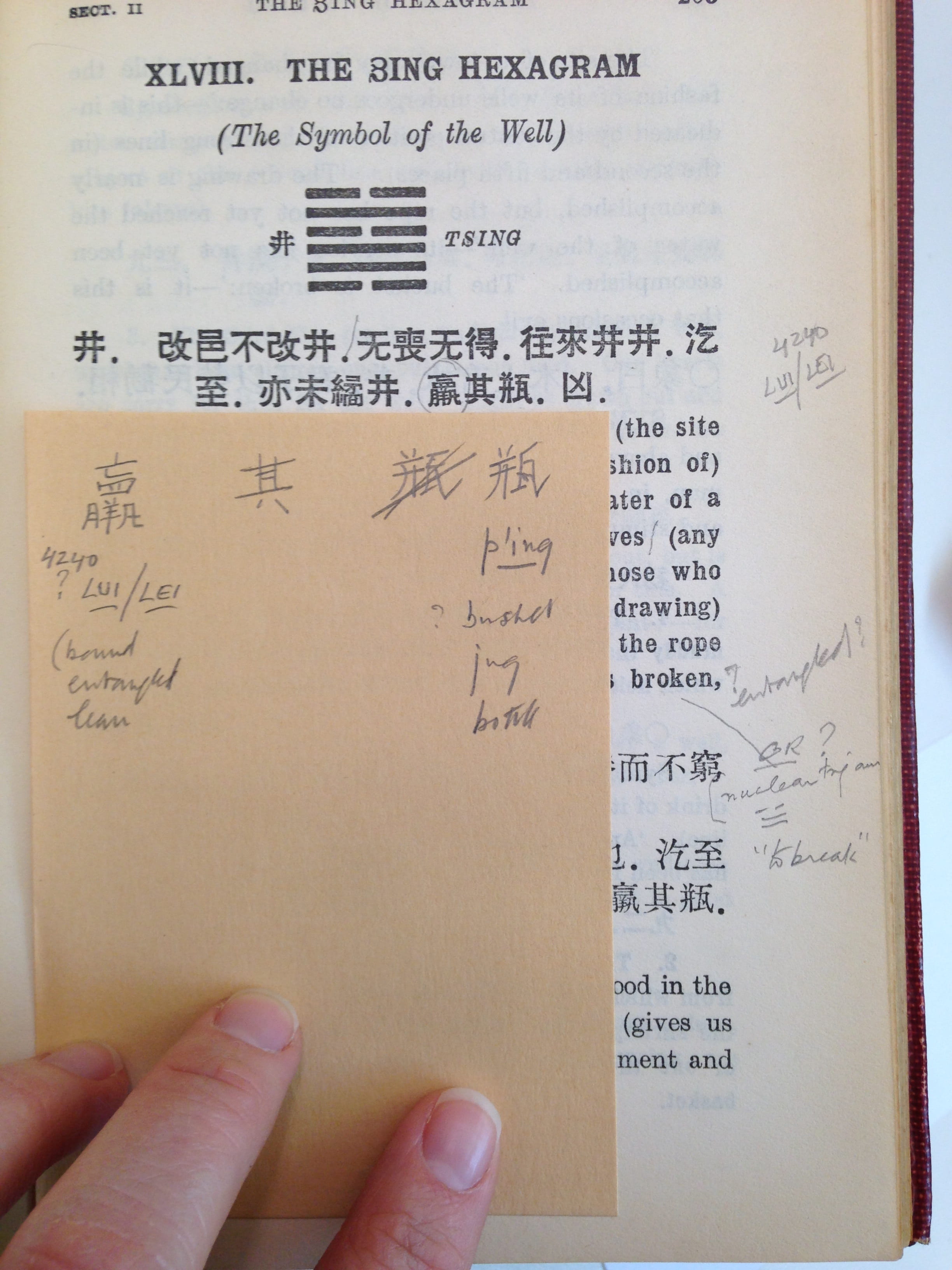

Sze’s most heavily annotated copy of the I Ching is one of only a few English translations with the text printed alongside the original Chinese. (She also owned an edited and annotated beginner’s edition entirely in Chinese, but this contains none of her characteristic penciled notes.) The Text of the Yi king (and its appendixes) Chinese original with English translation by Z.D. Sung, published in 1935 in Shanghai, contains typical Sze marginalia and inserts. Some characters are circled, and in the English text below she makes notes in English for alternate translations. On the inserted sheet of paper, she’s drawn out characters in question and jotted down a Wade-Giles pronunciation guide, with some further explorations of a possible English translation below.

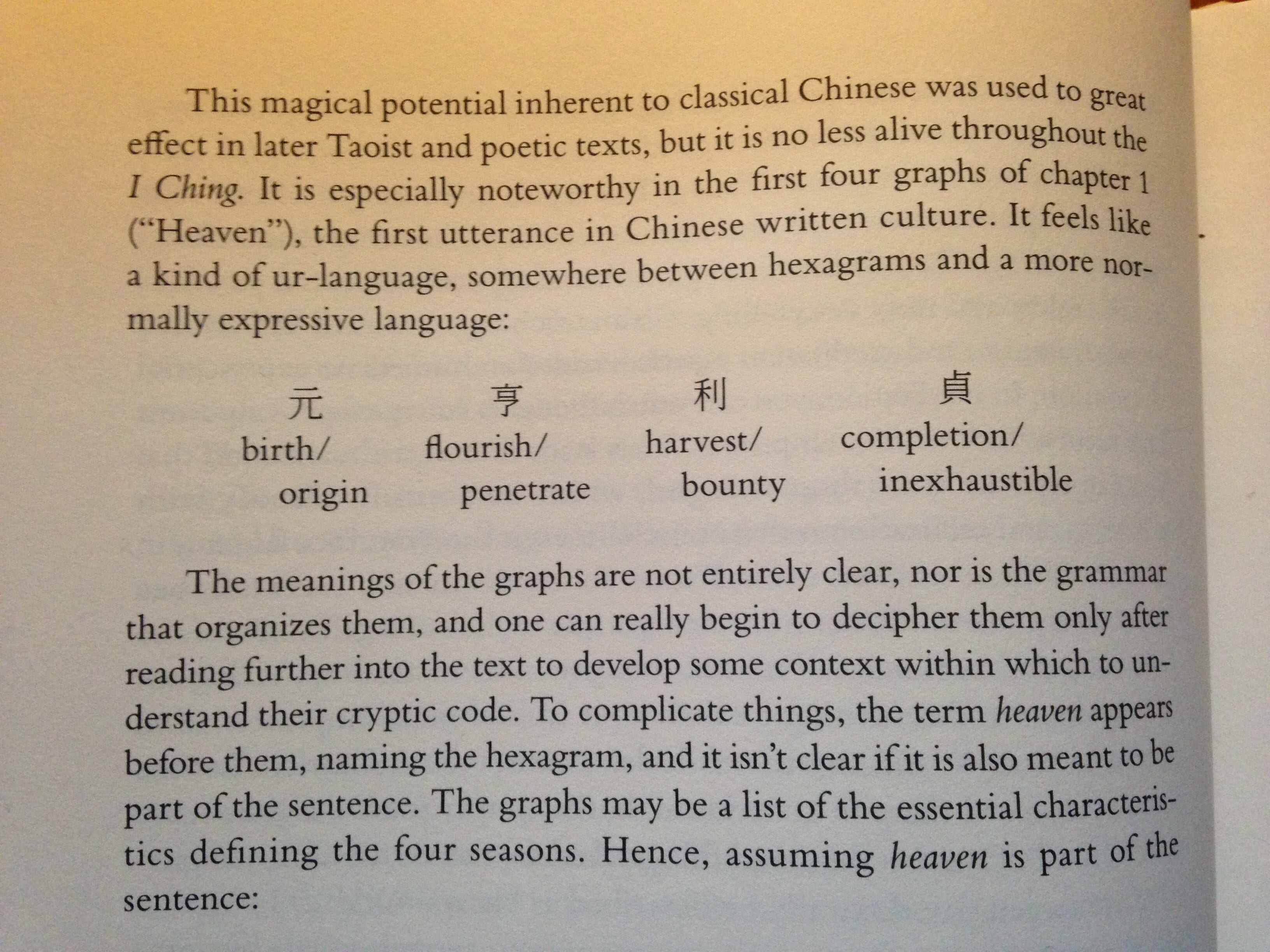

As David Hinton points out in the introduction to his new translation, the “texture of open possibility suffuses every dimension of the I Ching” because of the “wide-open grammar” of classical Chinese. The meanings of the characters are never precise. Verbs don’t indicate time with tense, and no punctuation was used, making it extremely difficult to extract a convincingly accurate English phrase from a cryptic string of graphs. To show how this works in practice, Hinton’s illustration looks much like one of Mai-mai’s annotations:

The original Chinese appears above English words whose meanings aren’t always closely related. This suggests that Sze was aware not only of the many possibilities for an English translation of a Chinese word, but also of the vast open territory to be covered by the translator in rendering the English into the Chinese. Her inclusion of phonetic transcriptions of the Chinese characters also indicates that she was clued into the importance of the sound of the original, which often rhymed.

The Sung translation of the text was described in the excellent 2002 annotated bibliography of the I Ching as a “convenient arrangement of the Legge translation,” as opposed to a totally new interpretation of the text in English. Sze referenced the Legge translation throughout the Tao of Painting, and kept up with new translations and secondary sources about the I Ching as they came out. Her collection includes copies of the Blofeld translation (Allen & Unwin, 1965), the previously mentioned two-volume Baynes-Wilhelm translation, and three studies of the book published by the Bollingen foundation by Richard Wilhelm, Hellmut Wilhelm, and the Russian scholar Iulian Shchutskii. All of them show the telltale signs of Sze’s intense engagement: TLS reviews are taped to the front covers, and the texts contain annotations in English and Chinese, with cross-references from one book to another.

Based on the surviving record, it seems clear that Sze’s most intense scholarly engagement with the text took place during the 1960s and 1970s; this period and the interaction were defined primarily by her engagement with the text in the original Chinese, as well as in English translations and studies published by the Bollingen Foundation. While the Bollingen angle is certainly worth investigating (particularly from a Jungian point of view), I’d rather close this piece by turning again to Hinton’s introduction and especially his discussion of how to read the I Ching. “As a poetic/philosophical text,” he writes, “it can be read like any other text, from beginning to end. However, even in this conventional reading, the book frustrates expectations of coherence. It is made up of fragmentary utterances, mysterious enough in and of themselves. And these fragments often feel quite disparate in nature: poetry alternates with philosophy, bare image with storytelling, social and political with private and spiritual, plainspoken and earnest with satire and humor” (xvii). As I’ve written previously on this blog, Mai-mai Sze’s interests were as wide ranging and complex as the I Ching that Hinton describes. Her library reveals her explorations of poetry and philosophy, visual art and literature, politics and social life, and spirituality, and I believe she saw all of these things at work in the I Ching.

With so many ellipses in the story of Sze’s life, it’s almost certain that there’s a more to this story than what I’ve been able to describe here. Like the I Ching, there’s always room for new interpretations when it comes to Mai-mai Sze. I hope these posts will inspire a new investigation.

Leave a Reply