By Madeline McMahon

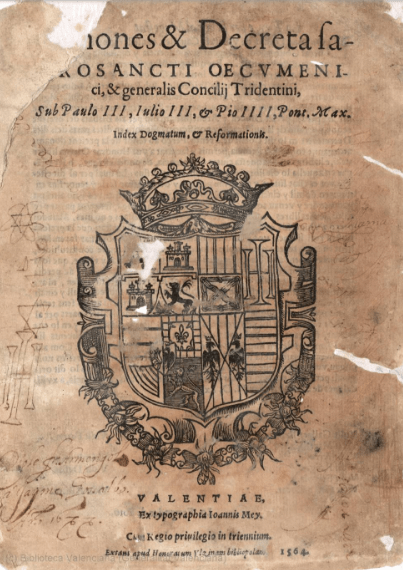

Canons and decrees are like the conference proceedings of church councils—polished, authoritative, and reflective of conversations, formal and informal, that nevertheless are often elided in the process of editing. As a meeting place for theologians, historians, and ecclesiastical authorities, the church council is an obvious site for intellectual history. Yet it can be tricky to chart that history, to disentangle the individual voices that contributed to the definitive, disembodied statements uttered by “the holy council” (mandat sancta synodus). After the Council of Trent ended in 1563, for instance, its decrees were published across the Catholic world. Revisions of liturgical texts—the missal and the breviary—soon followed in accordance with those decrees. So did a new catechism, a revised Vulgate, and the Index of prohibited books. These publications took on lives of their own as they were further revised, and, in some cases, revered or reviled. Yet what about the records from the council that did not get published? How can we recover the conversations that eventually became canons?

Sometimes we get a sense of the discussion from eavesdroppers. In 1416, the humanist Poggio Bracciolini attended the public hearing of the Hussite Jerome of Prague at the Council of Constance (1414 – 1418). In a letter to Leonardo Aretino, Poggio described how he listened, captivated, to “the eloquence and learning of the defendant.” Poggio quoted Jerome’s indignation at not being allowed to give a general defense speech rather than respond to each accusation one at a time. But it may be more accurate to say that the humanist, like a good classical historian, put words into his subject’s mouth. At one point, like a Cicero redivivus, Jerome exclaims to the ecclesiastics assembled, “O conscript fathers!” (patres conscripti). Compared with a quasi-official transcription from the council, Jerome incriminates himself far less in Poggio’s account (Renee Neu Watkins, “The Death of Jerome of Prague: Divergent Views,” 107). Yet Poggio also inserts specific readings of church fathers as well as the style of pagan orators into Jerome’s recorded speeches, suggesting, for example, that Jerome and Augustine had disagreed and that this was an argument for religious toleration (ibid., 108). Poggio’s depiction of Jerome’s stance thus differed substantially from the Hussite’s own. As Renee Neu Watkins put it, Jerome “believed…that he and Hus alone stood for the one just cause, the cause of the Church. Poggio suggests that eloquentia—that is, the classical moral tradition—offers another standard of justice” (120). This recorded conversation thus tells us as much about Poggio’s views as about Jerome’s.

Reading as well as speech feature in reports recording the 1529 Marburg Colloquy between Luther, Zwingli, and other Protestant reformers. Unlike the finished Articles, which stress the theologians’ agreement, an anonymous report begins with Luther acknowledging that in their “published pamphlets…they disagree” on important doctrinal issues and that he had even discovered by letter that “some Strassburgers” were saying that the fourth-century heretic Arius had taught more correctly on the Trinity than Augustine (“Anonymous Report,” trans. David Luebke 2). In addition to getting a sense of the earlier debate in print and rumors of theological contention on the street, these reports let us overhear an exegetical debate about the Eucharist at the colloquy itself. When arguing over the meaning of “this is my body,” Jesus’s words at the last supper, Zwingli demanded to know why Luther wants to understand the words literally. Oecolampadius, in support of Zwingli, cited Augustine’s exegesis of John’s gospel “that the body of Christ in which he rose must be in one place.” Luther, in turn, rejected the applicability of Oecolampadius’s reading to “this is my body”: “I say to this passage from Augustine…that it has nothing to do with the Lord’s Supper” (Heinrich Utinger report, Luebke, 13). The reports show the work of reading and discussion being done, while the Marburg Articles merely reference the friendly state of aporia the group reached: “at this time, we have not reached an agreement as to whether the true body and blood of Christ are bodily present in the bread and wine, nevertheless, each side should show Christian love to the other” (ibid., 17).

Pasquale Cati, Council of Trent (1588 painting in Santa Maria in Trastevere). Behind the allegory with the Church personified are a number of smaller discussions.

Like Heinrich Utinger’s report at Marburg, Gabriele Paleotti’s diary of the last two years of the Council of Trent, the Acta concilii Tridentini, is a semi-official account. Paleotti, a forty-year old judge at the Roman Rota, was sent to the council without voting power (Hubert Jedin, Das Konzil von Trient, 37). Joining the ranks of a number of other recorders, he kept eight notebooks on the final eight sessions, from January 15, 1562 to December 4, 1563 (ibid.). His Acta are immense—they take up over five hundred folio pages in the modern edition (Concilium Tridentinum…Collectio, III.233 ff.). His entries provide a glimpse of heated arguments between intellectuals of various national and linguistic backgrounds and theological and political convictions. The French delegates, for example, arrived even later than Paleotti, in November 1562; Paleotti’s diary depicts the crucial intervention of Charles De Guise, cardinal of Lorraine, on issues such as images and relics.

Another issue that occupied the Tridentine reformers in the final months was the appointment of bishops. Even before De Guise’s arrival, the French cardinal was rumored to believe “crazy things” about bishops—that they should be elected to office (Sebastiano Gualterio, quoted in Robert Trisco, “The Debate on the Election of Bishops in the Council of Trent” 262). In France and in much of Catholic Europe, rulers had often been granted the right to nominate successors to vacant sees in their territories. De Guise himself had been royally named an archbishop at the tender age of thirteen when his uncle, the previous archbishop of Reims, resigned (Trisco, 261). Yet on May 13, 1563, he stood before the council and argued that “election by the clergy took place according to the most ancient law out of the traditions of the apostles, although the confirmation was done by archbishops” (Paleotti, III.612, my translation). It was “absurd that even women, as in England and Scotland, who can neither teach nor speak in a church, nominate as bishops whomever they want” (III.613, my translation). (It is worth pointing out that the regent of France at this point, the ruler who had sent De Guise and his fellow French bishops to Trent, was Catherine de’ Medici.) To protect the church from the decisions of incompetent monarchs—whether minors or women—De Guise advocated for a return “to the form of the ancient church” (ibid.). Others immediately balked: “when the emperor, kings, and every commonwealth submitted to the decrees of this holy council,” that would be safeguard enough—as well as their due reward for the political support that the council needed (III.617).

The ultimate decision, delayed until November 1563, was to maintain the status quo but to impose higher standards: “Without wishing to change any arrangements at the present time, the council exhorts and charges all who have any right under any title from the apostolic see in the appointment of prelates, or assist the process in any way, to have as their first consideration that they can do nothing more conducive to the glory of God and the salvation of the people than to have every concern to appoint good shepherds who are fitted to guide the church” (ed. Tanner II.760). The tentative language hints at the contested nature of the decree—and the way in which the conversation developed to articulate what an ideal bishop should be like. Years later, when Paleotti was a bishop, he worked to revise his Acta of the council for publication. Such a publication would have been a kind of contemporary church history. But the changing and contested reception of Trent made it difficult, even impossible, to publish notebooks like Paleotti’s (Jedin, 39). The fluidity behind the final decrees was obscured, left for us to reconstruct from the letters, notes, and other records for an intellectual history of church councils.

May 25, 2016 at 4:24 pm

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.

August 28, 2017 at 5:29 am

No Problem 🙂