By guest contributor Benedetta Carnaghi

Two years ago I went to Ravensbrück. I went to Ravensbrück because I was shocked not to have been aware of its existence before reading the memoir of an ex-deportee. I went to Ravensbrück because I was appalled that, for no reason other than that it was the only Nazi concentration camp built especially for women, it is not as well known as other camps.

I was investigating Virginia d’Albert-Lake. Born in 1910, in Dayton, Ohio, Virginia had married Philippe d’Albert-Lake, a Frenchman working for the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company. She then moved to France. At the outbreak of World War II, they both decided to become involved in the Comet escape line, which eventually led to Virginia’s arrest in June 1944 and deportation to Ravensbrück.

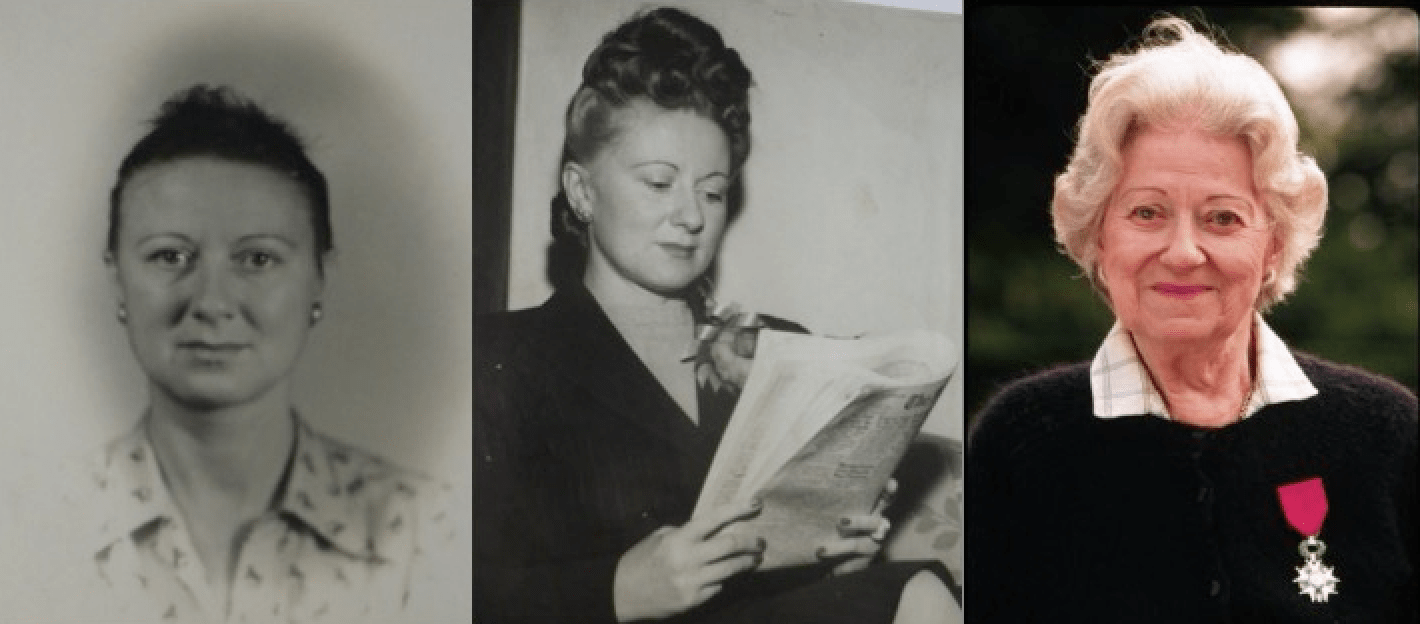

From left to right: Virginia d’Albert-Lake after her liberation; back in health; when she received the French Légion d’honneur (Private archives of the D’Albert-Lake family, Paris)

Virginia survived deportation and died in 1997. I was fortunate enough to interview survivors, and they explained to me that female deportation remains a taboo. Women were obviously present in concentration camps, but they seem to be nearly invisible in the historiography. Research and recognition has only recently improved. Sarah Helm published a group portrait of prisoners in Ravensbrück: Life and Death in Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women (2015). On May 27, 2015, Ravensbrück survivors Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz and Germaine Tillion were interred in the French Panthéon alongside resisters Pierre Brossolette and Jean Zay.

Francois Hollande (centre) stands on the Panthéon steps between the flag-draped coffins of Jean Zay, Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, Pierre Brossolette and Germaine Tillion. Source: The Guardian

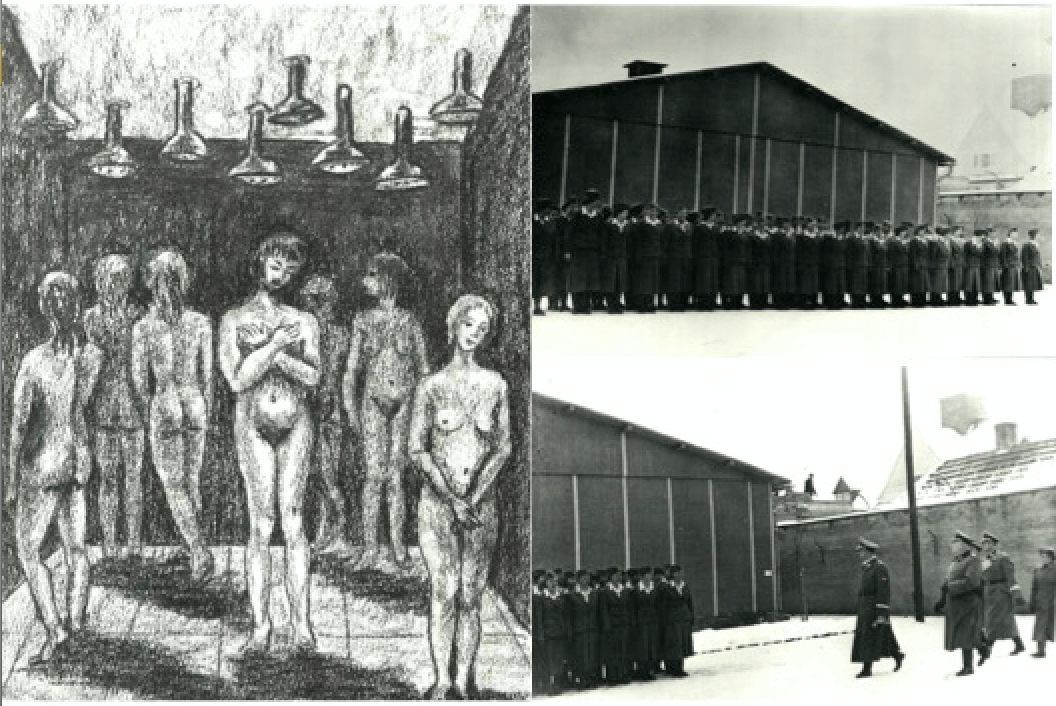

Margaret Collins Weitz’s conclusions as to why it took so long for these women’s stories to enter scholarship remain valuable, although her book Sisters in the Resistance (1995) was published two decades ago. It took a long time for women to “recount or write up recollections of their wartime experiences” (17). The rediscovery of their stories started with the French feminist movement of the 1970s and found a major touchstone in the first colloquium on “Women in the Resistance” organized by the Union des Femmes Françaises (UFF, Union of French Women) in 1975 (Collins Weitz, ibid.). But women were generally less interested in receiving recognition for their actions—that is, in filling out the official papers to be decorated or commended by the state. For those who survived deportation, the issue with “telling their story” proved more complicated. Deportation deprived them of every aspect of their femininity, forced them to parade naked at a time when nudity was taboo, exposed them to the insinuation that they had prostituted themselves to survive. They came back to a society that did not understand what they had gone through, and trying to explain it would have meant reliving the horror. Collins Weitz focuses, in particular, on “the dilemma of those who were, or subsequently became, mothers” and “found it impossible to tell their children of the horrors they had seen—and sometimes experienced,” in part because they did not want them to be marked by their personal stories (18). It was only to fight revisionist claims that extermination camps had not existed that the women found the courage to speak.

On the left: “Plus rien de personnel, plus rien d’intime” by ex-deportee Eliane Jeannin-Garreau ; on the right: Aufseherinnen greet Himmler during his visit of the Ravensbrück concentration camp in January 1941 (SS propaganda album – Archives of the Ravensbrück Memorial – Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Ravensbrück)

Nazis destroyed the barracks where the Ravensbrück deportees lived, but the houses of the SS guards still stand as a memorial and host various exhibitions. One explores the female SS guards, Aufseherinnen and Blockführerinnen, deployed there. I remember staring at their faces: their stories upset me. They were detrimental to my purpose of highlighting women’s heroism. At Ravensbrück I ignored them and kept my focus on the deportees.

But there they were, hundreds of them: on the walls of that house, in the back of my mind. I knew that the time would come when I would be forced to exhume the concerns I had buried and come to terms with the fact that there were women perpetrators among the Nazis. And that time came, indeed, when I read Wendy Lower’s Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields (2013).

Lower examines the women who were born in Germany in the wake of World War I, grew up in the Nazi regime, and worked for the Third Reich in the Nazi-occupied East, sharing responsibility for the massacres that were carried out there. Her research began in the town of Zhytomyr, in Ukraine. Lower originally traveled there to find documentation of the Final Solution, a quite impossible task. The town is about a hundred miles west of Kiev, and under the Nazi occupation, it was Heinrich Himmler’s Ukrainian headquarters.

The Nazis arrived in Ukraine in 1941 and ravaged the territory. Lower stumbled upon certain documents that listed ordinary German women living and working in towns like Zhytomyr during the Nazi occupation. She was surprised that such women would be in these areas. When she went back to the Western archives, she looked at the postwar investigative records and found testimony from many German women detailing the killings. Prosecutors appeared more interested in the crimes of their male colleagues and husbands. So Lower started wondering why prosecutors did not question or follow up on these women’s testimonies.

The female camp guards who triggered my thoughts were the only ones about whom studies existed when Lower set out to write her book. Compared to other German women working under the Nazis, the Aufseherinnen were fairly well-known, but according to Lower they were presented as caricatures or pornographic distortions of the “evil woman.” While there was a lot of literature about the different male perpetrators in the Nazi system, there were no sophisticated studies of the female perpetrators. Hannah Arendt herself “neglected the role of female administrators” when she “fashioned her thesis on the banality of evil” (Lower, 265). Yet the Cold War temporarily buried the question of the Nazi perpetrators, since “the Red Army became the ultimate war criminal entrenched in German experience” (Elazar Barkan, The Guilt of Nations: Restitution and Negotiating Historical Injustices, 2000: 10) and the German focus was on the nation’s suffering and its own victims. As for women specifically, the figure of the Trümmerfrau—the designation given to those who helped reconstruct the German bombed cities—was so powerful that it effaced every other representation of German women. Historian Leonie Treber defined it as a “German legend” and set out to dismantle the myth in her dissertation, but the controversy her work raised denotes how established this heroic image of women in post-Nazi Germany still is in today’s Germany.

The number of women perpetrators is not negligible. An estimated 500,000 German women went to the Nazi East and formed an integral part of Hitler’s machinery of destruction. Lower tried to understand why they did so, by closely studying their biographies. Their lives showed her how human beings change and how these women ended up contributing to the violence of the Holocaust, from the idealists who were allied with the Nazi ideology and saw themselves as agents of a conservative revolution, to those who simply followed their husbands or lovers and sought material benefits.

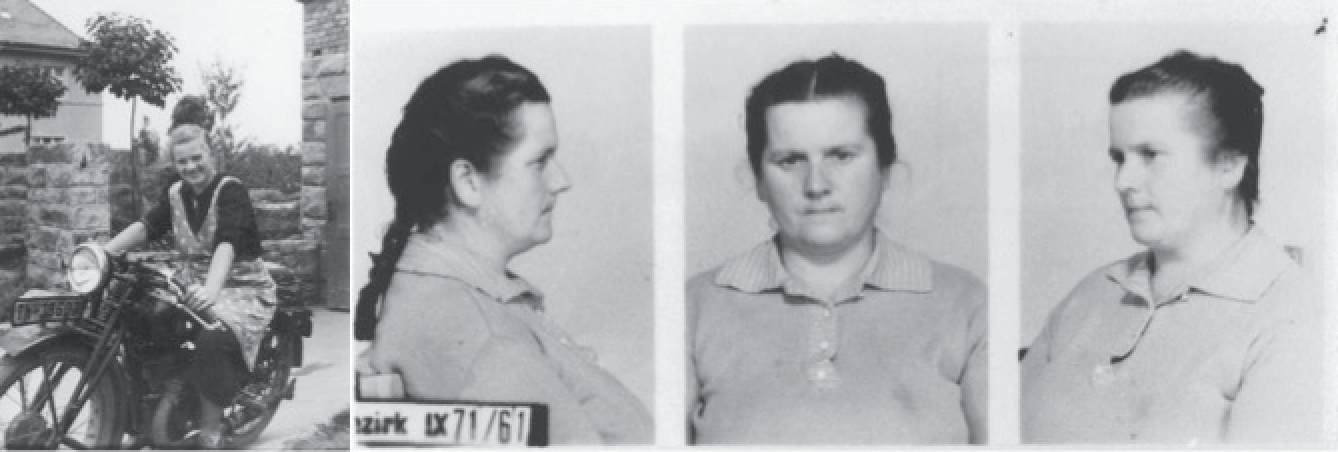

Erna Petri, before and after her arrest. Wife of SS Second Lieutenant Horst Petri, she shot six half-naked Jewish boys who had managed to escape from a boxcar bound for a gas chamber and were hiding on the Petris’ private estate in Nazi-occupied Poland. She was barely 25 years old at the time. When pressed by the Stasi interrogator as to how she, a mother, could murder these children, she referred to her own desire to prove herself to the men (the SS). Erna Petri “embodied” the ideological indoctrination of the Nazi regime. Source: Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields (p.88 and 205)

Paradoxically, it took Lower’s book about gender to teach me that evil is not gendered. Genocide is a human problematic behavior that applies to both men and women. “Minimizing women’s culpability to a few thousand brainwashed and misguided camp guards does not accurately represent the reality of the Holocaust,” writes Lower (182). Women should be given back their agency, whether good or bad.

The idea of “evil” has significantly evolved from the way Hannah Arendt first conceptualized it. Corey Robin analyzed her position in “The Trials of Hannah Arendt” and in a recent lecture delivered at Cornell University titled “Eichmann in Jerusalem. Three Readings: Hobbesian, Kantian, Arendtian.” Arendt tried to distinguish “Eichmann’s murderous deeds from his state of mind.” Eichmann was not a “solitary actor,” but a “partner in a criminal joint enterprise.” Arendt “de-emphasized motive” to stress the “collaborative dimension of mass murder.” Robin cites one of her letters to Scholem, where she famously said that “evil is never ‘radical’” but “only extreme,” and “it possesses neither depth nor any demonic dimension.” Robin argues that this is specifically “what Arendt’s critics detect and dislike in her thesis of the banality of evil: a denial of evil as the summum malum, of its capacity to serve as the basis of a political morality.” In such a quasi-Hobbesian interpretation of good and evil, there is no objective moral structure to the universe.

If for Arendt ideology played a lesser role in Eichmann’s decisions, it seems to me that Lower’s book resonates more with the way Timothy Snyder conceptualized evil. Nazism—just as Snyder framed it in his Black Earth: The Holocaust As History and Warning (2015)— supplied its perpetrators with a Weltanschauung and a rationale for their crimes, namely a fictitious life-and-death global struggle against an ultimate enemy, the Jew. Overall, a minority of women directly carried out the killings of Jews in the East, but many women participated in the administration, working to keep the wheels of the Nazi system turning, the deportation trains going and the documents moving. Their agency is visible in the goal they wanted to attain: to gain social mobility and be part of the new, selected “racial aristocracy” of the Third Reich.

Addition photos for the above piece can be seen here (courtesy of Benedetta Carnaghi)

Special thanks to John Raimo for his excellent suggestions on a previous draft of this piece!

Benedetta Carnaghi is a Ph.D. student in History at Cornell University. She studies modern European history with a particular focus on Italy, France, and Germany. Her current research focus is a comparison between the Fascist and Nazi secret police. Related interests include the history of Resistance, the Holocaust, gender studies, political violence, and terror.

June 8, 2016 at 8:16 am

informative

June 8, 2016 at 4:58 pm

For those who are interested in further exploring the question of radical evil, Paul Ricoeur and Jorge Semprún are also worth mentioning. Ricoeur admitted the existence of radical evil but found it to be “inscrutable”: he wrote, “there is no comprehensible reason of knowing where this moral evil could originally have come from” (Ferrán, Ofelia, and Herrmann, Gina eds. “A Critical Companion to Jorge Semprún: Buchenwald, Before and After.” New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014: 159. Link: https://books.google.it/books/about/A_Critical_Companion_to_Jorge_Semprún.html?id=1KTioAEACAAJ&redir_esc=y). Jorge Semprún built on Ricoeur’s phenomenological approach, as well as the interpretations of Emmanuel Levinas and Catherine Chalier, but he recuperated human agency: he argued that “the propensity to evil is grounded in the liberty that, in turn, is a ground of human being” (ibid.). Evil paradoxically becomes “the supreme affirmation of man’s humanism, of his humanity” (ibid., 160).

June 8, 2016 at 7:24 pm

Here is a link to a slideshow with some additional photos: http://www.photosnack.com/BenedettaCarnaghi/unveilingevil.html