By guest contributor Paul Babinski

In 1783 Karl Philipp Moritz went to Berlin’s Charité hospital looking for a human guinea pig. What we know of the deaf teenager he brought home, Karl Friedrich Mertens, comes from two accounts Moritz published in his journal of experiential psychology, the Magazin zur Erfahrungsseelenkunde. The encounter is only a footnote, if that, in the history of deaf pedagogy, but it is a fascinating window onto the experience of the late Enlightenment German thinker as he grappled with disability and the humanity of the disabled at a moment when their supposed limitations were being enshrined in the hierarchies of cold, pseudo-scientific certainty.

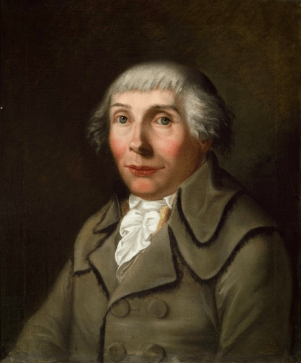

Moritz is remembered today for his autobiographical novel, Anton Reiser, whose intense, often brutal psychological self-observation Moritz had cultivated with a circle of collaborators in the pages of the Magazin zur Erfahrungsseelenkunde. Moritz took in Mertens to see for himself about a debate that had sprung up in European journals. Was it better to teach deaf students to speak or to use signs? This split between so-called oralist and manualist methods remains today a contentious topic. The controversy reached the European stage in 1779, when Joseph II founded the Taubstummeninstitut (Deaf and Dumb Institute) in Vienna.

Ponce-Camus, the Abbé and the Comte de Solar

Joseph II had been inspired by the Parisian Abbé de l’Épée who took in deaf street children and taught them using “methodical signs,” the pre-cursor of modern sign language, which the Abbé had developed by combining grammatical elements with the signs already in use among his students. He believed that his work would uncover a natural universal language—a kind of silent lingua franca for transnational communication. When the Abbé claimed that a young boy in his care was in fact the abandoned son of a French noble, the Count of Solar, the ensuing scandal raised awareness of the Abbé’s methods. The Affaire Solar, which provided material for a popular play decades later and several films in our own time, distilled the dawning awareness that the Abbé’s project reclaimed the basic humanity of a marginalized group whose station in life was the sign not of a natural order, but of past wrongdoing committed against them.

The increased attention also ensnared him in one debate after another, as various pedagogues came out of the woodwork with competing theories. With the adoption of the Abbé’s methods in Vienna, the young director of Leipzig’s school for the deaf, Samuel Heinicke, took up the German oralist counter-offensive. Heinicke’s methods were cobbled together from a variety of earlier published sources, most significantly the work of Johann Konrad Ammann, whose 1692 Surdus loquens outlined a method for teaching the deaf to speak. Building on Ammann, Heinicke developed a method of training vocal production by mapping it onto a scale of flavors, and he used what he called a “Sprachmaschine,” an anatomical model of the speaking organs, in instruction. These he kept “secret,” refusing to divulge the details of his methods without a substantial cash reward.

Holding useful knowledge ransom did not endear him to the republic of letters – nor did the excessive discipline with which Heinicke was rumored to handle the students in his care – but Heinicke’s ideas nevertheless convinced many of his German contemporaries. He argued forcefully against the use of signs, going so far as to group the Abbé’s methods alongside the cruel surgeries and electric shocks that doctors and charlatans inflicted on deaf children to “cure” their silence. More significantly, Heinicke presented the hodgepodge of ideas he had culled from earlier works in the tantalizing and novel garb of cognitive psychology. The deaf, he argued, simply think differently.

To illustrate his point, he compared the child learning to speak to the apprentice typesetter, who must know not only the letters, but their place in the type case and the feel of the nick with which the individual letters are oriented on the composing stick. Heinicke invites us to follow the beginning apprentice’s thought as it follows the awkward movement of his hand from the copy, to the type, to the nick, letter by letter. With experience, however, this process becomes automatic, and the typesetter’s attention can rest solely on the text itself. So is it with concept formation, Heinicke argues. Like the typesetter’s station, sound and speech provide the sensual basis upon which the basic workings of thought are mastered, and it is to these sensations that visual signs in turn refer. Without this spoken referent, the written sign appears jumbled and unintelligible or, if ever grasped, is unable to take root in memory. Without a foundation in these basic, embodied cognitive processes, deaf children would remain forever grounded in the immediate and the material, and never graduate to abstract thought. Heinicke spoke often of Denkarten (ways of thinking). There was, he explained, a speaking Denkart and a “deaf-mute” Denkart, and the latter was fundamentally inferior, like the thinking of a child.

Moritz and his collaborators were intrigued by these ideas, even if Moritz seemed hesitant to embrace Heinicke and his less-than-stellar reputation. In his journal, he staged the oralist-manualist debate that Heinicke had picked with the Abbé, printing excerpts from their letters, and later published Friedrich Nicolai’s critical account of his visit to a public examination at the Vienna Taubstummeninstitut, whose director had trained with the Abbé, as well as observations on deaf individuals from other contributors.

Magazin zur Erfahrungsseelenkunde (1786)

However, it is the account of his cohabitation with Mertens, the boy he took in from the Charité, that is perhaps the strangest, and most fascinating, monument to Moritz’s experiments in deaf pedagogy. Moritz at first wanted to teach the boy to speak, like Heinicke advocated. The first of his two entries in the Magazin für Erfahrungsseelenkunde follows his efforts to teach Mertens to produce individual sounds. He describes in detail how quickly his pupil picked up the basics, mimicking the way Moritz moved his mouth and intuitively grasping that he should imitate his teacher’s hand movements with his tongue. “After four weeks,” Moritz reports, “he could already bring forth various two-syllable words, such as flower, paper, etc., as people who have seen him at my place know.”

In the meantime, unexpected lines of communication sprung up between the two. It struck Mertens, as he watched Moritz and a friend reading together from the same book, that he’d seen the two before when he was living “wild on the street” and rowing boats to make a little money. Moritz and his companion had read like that once as he rowed for them. The boy energetically told the others through gestures and signs, and Moritz wondered at the vividness with which Mertens could recall the event. The deaf, he noticed, had perfectly good memories.

Soon the oralist instruction fell away and, in the second installment, Moritz simply observed the young boy for those qualities of mind that Heinicke claimed were inaccessible to the deaf “way of thinking.” How were his judgement and imagination? Did he understand the abstract concepts of Christianity? When, unprompted, Mertens covered the portals of their house with crosses on Walpurgisnacht – April 30th, when the witches fly to the Blocksberg to have their sabbath – Moritz noted that he could think calendrically. To find out whether or not he considered suicide a sin, Moritz held a knife to his breast and made like he would plunge it in. Mertens explained through gestures that if he did so the devil would take him and stomp him to bits. Another time, Moritz lay in bed like someone dying as a way of asking Mertens what would happen to him after death. We can only imagine what Mertens thought of his new roommate, the strange intellectual with his theatrical scenarios meant to probe the boy’s inner state.

Piece by piece, Moritz located the inventory of conceptual thought in Mertens and dispelled Heinicke’s myth of the inferior “deaf-mute’s way of thinking.” What he found instead was something all too human, a complicated personality, hurt, resentful, often vain, and at times consumed by anger. It was, I think, with an empathetic look to Mertens that Moritz later said of a deaf boy in his novel Andreas Hartknopf that “envy and self-interest had taken root so deeply within him that he begrudged the flower sunshine or the flock camped beneath a tree the shade.”

In fact, the line that separated Moritz from his deaf pupil was a more familiar one: between Enlightened rationality and small-minded prejudice and superstition. Berlin’s Jewish intellectuals, like Moses Mendelssohn, Salomon Maimon, and Marcus Herz, counted among Moritz’s friends and collaborators, and the fiercely anti-Semitic Mertens disapproved of Moritz’s Jewish visitors. At one point, “he formed with his fingers the figure of two horns on his head, and pointed to the fire burning in the oven, expressing through pantomime that the devil would lead the Jews to hell.” The boy chided Moritz for not going often enough to church (though he never went himself), was convinced Moritz withheld money that the state had supposedly given him for Mertens’ care, and seemed unsure if his host could even be counted among the saved. He was quick to hold a grudge. Threatening those whom he felt had wronged him with divine retribution, he evoked in gesture the lightning with which God would smite his enemies. If the Affaire Solar narrated the realization of the marginalized deaf child’s humanity with a grand scale and hopeful optimism fit for the popular stage, Moritz’s case study was its gritty, realist counterpart.

In an essay containing his theoretical conclusions on the subject, Moritz does not entirely do away with Heinicke’s link between the use of signs and cognitive limitation, but he implicitly rejects the oralist method. He compares the arbitrariness of spoken words, a “light tool for thought,” with the often unwieldy gestures that he fears can never truly break free from the objects they signify. Nevertheless, he advises that we constantly strive to simplify these signs, “with which the deaf-mute seeks to order in his mind the world around him.” It is hard not to see echoes of his depiction of Mertens when Moritz cautions that otherwise, “[the surrounding world] would seize hold of him, and represent itself more within him than he himself can conceive of the world.”

Paul Babinski is a PhD student in German at Princeton University. He is writing his dissertation on early modern German orientalism.

Further Reading:

Joachim Gessinger, Auge und Ohr: Studien zur Erforschung der Sprache am Menschen: 1700-1850 (Berlin: de Gruter, 1994).

Jonathan Ree, I See a Voice: Deafness, Language and the Senses – A Philosophical History (New York: Holt, 1999).

June 15, 2016 at 10:33 am

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.

April 1, 2017 at 5:33 pm

Magazin zur, not für!