Interview conducted by contributing editor Brooke Palmieri

The longer you stare at the words “public intellectual” the harder they are to decipher. They imply the application of thought to everyday life, they imply that the “intellectual” has something of value to give to a “public.” But they are also so grand as to push their own ambitions into the realm of pure fantasy: who counts as an “intellectual,” and how are they supposedly improving a “public” with their opinions? At least, difficulty grappling with the gap between what a public intellectual is and ought to be is a symptom of reading Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft’s new book, Thinking in Public: Strauss, Levinas, Arendt (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

Wurgaft shows just how young the word “intellectual” is— it arises as a description of a type of person in France during the Dreyfus Affair — yet it is powerful enough to influence our evaluation, and exaltation, of thinkers long dead and into the present. Wurgaft considers Strauss, Levinas, and Arendt’s relationship to the practice of philosophy in the wake of the Dreyfus Affair, and their studies under Martin Heidegger. But in covering “the intellectual question” at the heart of their works, Thinking in Public is as much about how we write intellectual history as it is about how we might live as intellectual historians. He urges us not to take for granted the value, nor the authority, of “intellectuals”. Instead, the tension between theory and practice, philosophy and politics, must be constantly re-evaluated, and while Wurgaft shows how that process of re-evaluation is the premier question in the writings of Strauss, Levinas, and Arendt alike, Thinking in Public also reads as a provocation to scholars today, creating space to reflect on the value of public engagement in a world where ignoring it is no longer possible.

Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft, author of Thinking in Public: Strauss, Arendt, Levinas (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016)

JHI: I don’t think you could bring the level of energy and thoroughness to “the intellectual question” that you do if there weren’t some personal ghosts haunting you on the subject of intellectual accountability. How did the topic of Thinking in Public come about? What is your investment in the subject?

BAW: Although I think of it as a traditional work of intellectual history, moving between close readings of texts, contextualization, and interpretation, Thinking in Public is also a counterintuitive book. Where many books about the figure of “the intellectual” advocate for the importance of such persons, or provide a theoretical account of their social or political role, Thinking in Public examines the meaning of discourse about “intellectuals,” especially for a generation of European Jewish thinkers for whom such figures had a particular resonance. Ever since it appeared during the Dreyfus Affair, the figure of “the intellectual” has served as a screen onto which we project our longings, including longings for the life of the mind to influence the political world. Thinking in Public is a book about how Leo Strauss, Emmanuel Levinas and Hannah Arendt understood the connections and gulfs between philosophy and politics, and it’s the first full-length comparative study of these three thinkers.

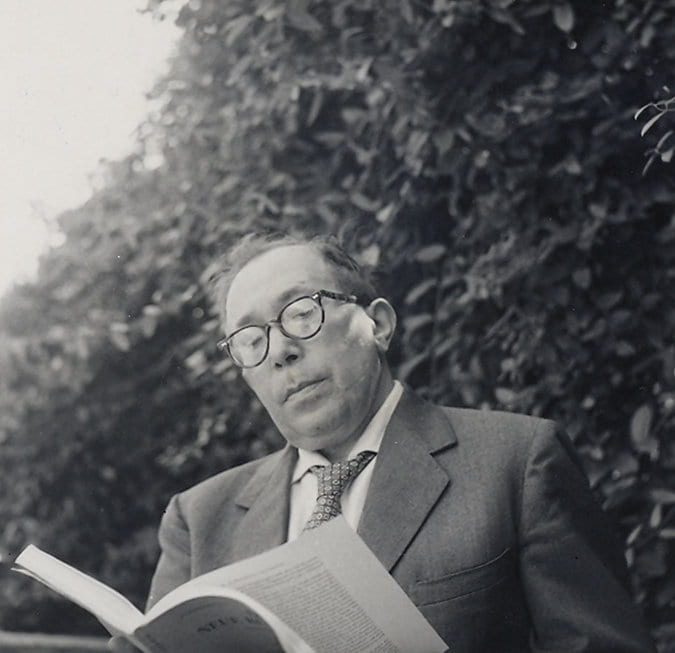

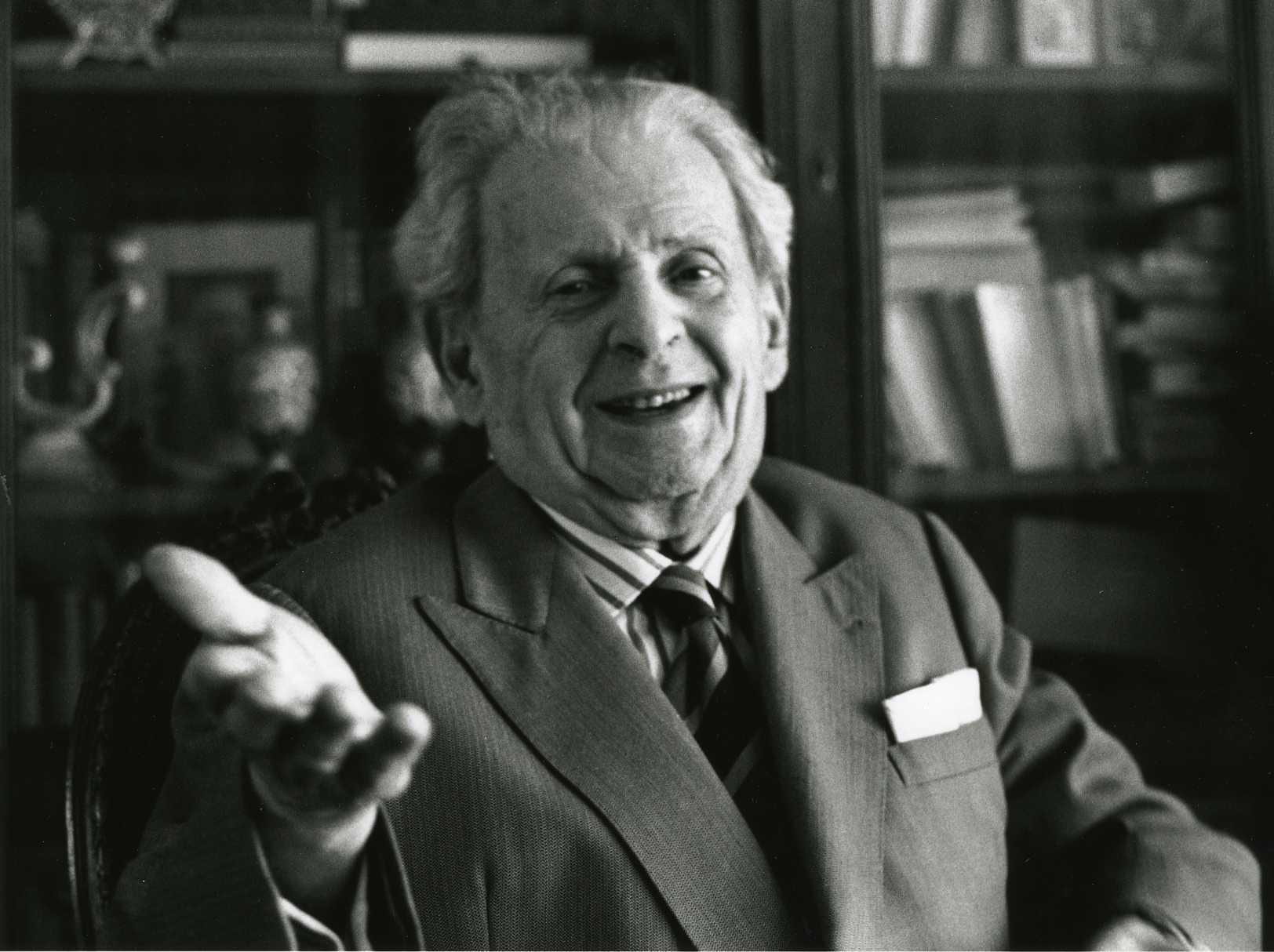

More personally, Thinking in Public is my first book-length work in intellectual history. Thus it’s the book of a writer trying to synthesize and respond to years of education, and to express a set of mature new thoughts. And of course I’m trying to deal with the conceptual errors of my younger self! I arrived at Berkeley to study intellectual history and modern Jewish thought, thinking of writing on the French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995), on whom I had written an undergraduate thesis at Swarthmore, with the wonderful guidance of Nathaniel Deutsch. At Berkeley, under the mentorship of Martin Jay, I emerged as a scholar of modern European intellectual history more primarily, but many of questions remained from my earlier work on Levinas, and my studies in modern Jewish history with John Efron. I started off wanting to write about efforts to “correct” philosophy in the wake of the Holocaust, which is certainly one way to summarize Levinas’s mature project, but I grew skeptical about Levinas on several levels. For one, his idea of “ethics as first philosophy” began to seem weak to me, and then there was his seeming elision between philosophy and politics – between the ideas of “totality” and “totalitarianism,” you might say. I reached for Arendt and Strauss because, like Levinas, they had studied with Martin Heidegger in their twenties, and, also like Levinas, they made either direct or indirect claims about the way the life of the mind was implicated in the political disasters of the twentieth century. I discovered that the figure of “the intellectual” served all three as a means by which to describe the relationship between philosophy and politics. And the impulse to describe that relationship stemmed not only from political crisis, but also from a sense that philosophy had somehow gone astray. The idea of comparing their views on intellectuals, on the predicaments of modern Jewish identity and history, and on the philosophy-politics dyad, flowed from there fairly naturally.

More personally, Thinking in Public is my first book-length work in intellectual history. Thus it’s the book of a writer trying to synthesize and respond to years of education, and to express a set of mature new thoughts. And of course I’m trying to deal with the conceptual errors of my younger self! I arrived at Berkeley to study intellectual history and modern Jewish thought, thinking of writing on the French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995), on whom I had written an undergraduate thesis at Swarthmore, with the wonderful guidance of Nathaniel Deutsch. At Berkeley, under the mentorship of Martin Jay, I emerged as a scholar of modern European intellectual history more primarily, but many of questions remained from my earlier work on Levinas, and my studies in modern Jewish history with John Efron. I started off wanting to write about efforts to “correct” philosophy in the wake of the Holocaust, which is certainly one way to summarize Levinas’s mature project, but I grew skeptical about Levinas on several levels. For one, his idea of “ethics as first philosophy” began to seem weak to me, and then there was his seeming elision between philosophy and politics – between the ideas of “totality” and “totalitarianism,” you might say. I reached for Arendt and Strauss because, like Levinas, they had studied with Martin Heidegger in their twenties, and, also like Levinas, they made either direct or indirect claims about the way the life of the mind was implicated in the political disasters of the twentieth century. I discovered that the figure of “the intellectual” served all three as a means by which to describe the relationship between philosophy and politics. And the impulse to describe that relationship stemmed not only from political crisis, but also from a sense that philosophy had somehow gone astray. The idea of comparing their views on intellectuals, on the predicaments of modern Jewish identity and history, and on the philosophy-politics dyad, flowed from there fairly naturally.As your question anticipates, Thinking in Public reflects the quirks of its author, in particular my love of puzzles, paradoxes and contradictions in the life of the mind. Because that’s precisely what the figure of “the intellectual” presents us with. Allowing myself to backtrack for a moment, one of the reasons I practice intellectual history is because I want to understand the way ideas change over time, and to understand the reasons for those changes. Often the ideas in question are crafted by philosophers or social theorists, but here “ideas” could refer to the conceptual infrastructure that guides and supports intellectual life, and the idea of a social type called “intellectuals” or, in the Anglophone world, “public intellectuals,” is one part of that infrastructure, just as institutions such as journals, magazines, and academic departments are practical forms of infrastructure. But some concepts produce more confusion than others, and discussions of “intellectuals” or “public intellectuals” strike me as quite complex and messy, and in a way that apparently attracted me.

I didn’t want to write a book about intellectuals that would celebrate the social role of such persons, try to map their development historically, or tie a basically functionalist account of intellectuals to a basically functionalist account of public political life. Many such books already exist, and it seems to me that their real function is one of ideological contestation rather than scholarship—praising heroes or damning villains, depending on the politics of the author. I wanted to understand how a series of crises, ranging from the apparent weakness of liberal democracy in the Interwar years all the way through the rise of totalitarian governments through a growing awareness of the Holocaust, made philosophers and political theorists reconsider what it meant to practice their crafts, and even reconsider the substance of intellectual life itself.

JHI: There’s a lot to disentangle about the idea of an “intellectual.” In the book it emerges as a noun that is incredibly relational—giving a name and a location to clashes between philosophy and politics above all, but from there between the private and the public, the individual and society. You show how Arendt, Levinas, and Strauss alike think that philosophy and politics are “basically incompatible” on the one hand, but on the other, that incompatibility doesn’t stop them (especially Arendt) from embodying the role in certain circumstances. What do you think causes them to suspend their logic for the sake of action?

BAW: The book has two parts: in the first, I examine Strauss, Levinas and Arendt’s intellectual biographies with a special focus on their discussions of “intellectuals” and their shifting understandings of how philosophy relates to politics. Those are two very different issues, but sometimes complaints about “intellectuals” become surrogates for complaints about the fate of philosophy on the contemporary European scene – or the American one, because both Arendt and Strauss take refuge in the U.S. and ultimately take citizenship. In the second part, I compare their views, and also explore the senses in which their views were influenced by their varied receptions of modern Jewish history. So, on the one hand the book contributes to ongoing conversations about intellectuals, and on the other it’s definitely part of the sub-genres of books on German Jewish thought and on the wave of intellectual émigrés who reached America in the middle of the twentieth century. But I don’t want to appear to believe that there’s a “core” to Arendt, Levinas or Strauss. Intellectual historians may inevitably engage in synopsis and paraphrase as we conduct our work, but I think we need to be careful to show that a thinker’s views do change over time, and that most writers display the all-too-human feature of inconsistency.

As you say, Hannah Arendt certainlydisplays some of the features we commonly associate with the “intellectual” or “public intellectual,” writing on everything from the rise of totalitarianism to the aftermath of the Holocaust to the Pentagon Papers. But what’s really interesting is that Arendt’s greatest apparent failures to understand her audiences, the times when she genuinely offended the sensibilities of people whose agreement she might have sought, occur in cases when she most badly wants to maintain her right to judge by the most stringent standards of detachment – you might say that these are cases in which she refuses to suspend her logic for the sake of action. And I don’t think she ever saw herself as abandoning her sense of the tension between philosophy and politics, when she wrote for wide audiences; after all, the philosophically-trained Arendt disavowed the identity of “philosopher” in her maturity. She seems to have thought that the sheer importance of the public events she wrote about, demanded the full severity of her method. She was no rhetorician, trying to craft her work to persuade her audience. Instead she invited them to think with her. I suppose this is one reason she’s been criticized as an elitist, but I find her insistence on principles very admirable.

But this leads me to one central theme in Thinking in Public: publicness and the figure of the intellectual don’t produce simple antipathy and rejection, for Arendt, Strauss and Levinas. There’s a real ambivalence, a push and pull. Even Leo Strauss, who took the idea of a philosophy-politics incompatibility further than either Arendt or Levinas, felt that he had to respond to the predicaments presented by publicness in the twentieth century; he just chose to do so as a scholar rather than as a writer for popular audiences. Incidentally, Thinking in Public’s main provocation may be to enthusiastic readers of Arendt and Strauss, because I argue that they shared a view of the incompatibility of the vita contemplativa and the vita activa (to use Arendt’s terms) usually attributed to Strauss; their real difference is that Strauss found a basically non-worldly version of philosophy worthy of endorsement, and Arendt did not.

But, along with Levinas, Arendt and Strauss understood that in the twentieth century publicness becomes a kind of unavoidable condition, in Heidegger’s terms something into which we find ourselves “thrown.” What I find especially suggestive is that all three thinkers find ways, ranging from Levinas’s “ethics as first philosophy” to Strauss’s picture of the philosopher in the city to Arendt’s late meditations on internal dialogue, to understand how certain kinds of interpersonal encounter are there at the very beginning, coeval with the practice of philosophy and in some cases prior to it. Philosophy may not be a sociable practice, but for all three it is always conditioned by the possibility of interpersonal encounter. Indeed, Strauss thought that political philosophy was developed in order to protect philosophy proper from the chaos and danger to which the political life of the city was vulnerable.

JHI: I realize you’re not trying to argue for the social importance of intellectuals. But, since you wrote Thinking in Public at a time when the humanities are under attack and regularly dismissed, do you think there’s a need to do more than retreat from public life? Wouldn’t that be a form of abjection? It might even mean abandoning the premise that the humanities improve us – and improve the publics through which they circulate.

BAW: I’m really glad you brought this up. I’m not suggesting retreat, I’m trying to describe some of the complexities of the inevitably public life of the mind. In the early twenty-first century attacks on the humanities occur, ironically enough, at a moment when the Internet makes our intellectual lives increasingly public, whether this is through magazines like the Los Angeles Review of Books (for which I often write, these days), or through the circulation of lectures via YouTube, or through all the other forms of intellectual life that make sophisticated scholarship available beyond the colleges and universities. We obviously have to fight to defend the humanities and social sciences within our educational institutions, and this entails public speech. But what kind? What sort of authority or legitimacy do we wish to claim for the humanities, and to which arguments about their power to improve us, via education, do we want to commit ourselves? That’s the kind of conversation Thinking in Public might point towards. After all, Arendt and Strauss both placed special stress on the civic importance of education, and Levinas spent much of his career as a school administrator.

JHI: Wittgenstein’s concept of “family affinities” is a lovely methodological alternative that you draw from to justify the selection of Arendt, Levinas and Strauss. Who do you have family affinities with?

BAW: You have me feeling even more self-conscious than usual! Bluntly put, “family resemblance,” Wittgenstein’s concept, may appeal to me because I have an anthropologist’s appreciation of the subfield of European intellectual history as a kinship network. That network has been shaped not only by the bonds (and the squabbles) between students and teachers, but by all kinds of other ties as well. It would be very funny to try to construct a kinship chart for the subfield, and maybe I will someday. I’m obviously Martin Jay’s student, and while he doesn’t try to shape his students into a “school” I was certainly influenced by the “paraphrastic” or “synoptic” style of intellectual history associated with him – see, for example, his wonderful essay “Two Cheers for Paraphrase: The Confessions of an Synoptic Intellectual Historian.” And I’ve been the beneficiary of a supportive network of his former students, who were becoming established in the field just as I was working on my doctorate.

But “resemblance” conjures more than direct relation, and your question reminds me of my debts outside my own field. This is a point that has been widely appreciated by others, but I’ve long thought most intellectual historians have an elective affinity for the figures they write about. Thus someone writing about economists or art historians or modernization theorists or phenomenologists needs not just technical vocabulary and inside knowledge of these fields, but also a sympathy for their subjects, even to the point of wishing, on some level, to be one of them. When I write about the history of philosophy it’s partly out of my conviction that philosophical questions and propositions are best understood in light of their times, and in light of the prejudices, fortunes and cultural surround of those who posed them. But it’s also because I want to try to pose those questions and propositions anew. My own short list of influences beyond intellectual history, people whose works influenced me greatly, would include Judith Butler (whom I was lucky to work with at Berkeley), Stanley Cavell, James Clifford, Stefan Helmreich (I’ve benefited from his guidance at MIT), and Steven Shapin.

JHI: What is your next project and do you see it relating to Thinking in Public?

BAW: My next or, I suppose, current project is about biotechnology and the future of food, but it’s also a work of intellectual history with a few connecting threads back to Thinking in Public. As I completed the dissertation out of which Thinking in Public eventually grew, I was intrigued by Arendt and Strauss’s shared antipathy towards the idea of progress, especially progress made possible by technology; in the Prologue to The Human Condition, which was published in 1958, Arendt is especially upset about dreams of transforming the human condition by, variously, leaving the Earth for a life on other worlds, or of modifying our own biology in order to transcend such fetters as the human lifespan. Such doubts about the idea of “progress” certainly aren’t unique to Arendt and they bear at least some comparison to criticisms of the idea of progress made by her co-generationists in the Frankfurt School. Both the idea of progress and its critique were striking for me as a graduate student in the Bay Area, which was ground zero for techno-utopianism as I was finishing my doctorate. I became interested in the history of science and technology, but graduate school didn’t afford much time for them.

But it was my good luck that, in 2013, after my first postdoctoral fellowship at the New School had ended, I received a grant from the National Science Foundation, intended for post-Ph.D. scholars who want to add the history and anthropology of science, or other science studies fields, to their areas of competency. The grant funded a second postdoctoral fellowship, in Anthropology at MIT, and it was an incredible gift to have those additional years of study. My new book project, drawing on several years of ethnographic work conducted during that fellowship, focused on precisely the ideas of progress that Arendt once criticized. I’m writing about contemporary efforts to grow meat in laboratories via cell culture techniques, an effort designed to fix the massive problems in our system of animal agriculture and meat production. The resulting book will weave together the anthropology and history of science, intellectual history and food studies, and I hope to make some contributions to the history of the future of food, as well as to the history of the philosophy of life – Arendt’s friend Hans Jonas will be a major figure for me in this book, as will Hans Blumenberg, for whom the categories of the “organism” and “the artifact,” and the tension between them, determine much about modern intellectual history. But if Thinking in Public is a traditional work of European intellectual history, I’m now interested in writing something that feels genuinely new in both method and content.

Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft lives in Oakland, and is a visiting researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he writes about laboratory-grown meat and the futures of food. A native of Cambridge, Massachusetts, he studied at Swarthmore College and did his graduate work in European intellectual history at Berkeley. In addition to his scholarly work, he regularly writes on contemporary food culture. He is @benwurgaft on Twitter. The editors thank him for very kindly agreeing to be interviewed for the JHI Blog.

June 27, 2016 at 8:18 am

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.