by guest contributor Jonathan Kearns in collaboration with Brooke Palmieri

Nor is the empire of the imagination less bounded in its own proper creations, than in those which were bestowed on it by the poor blind eyes of our ancestors. What has become of enchantresses with their palaces of crystal and dungeons of palpable darkness? What of fairies and their wands? What of witches and their familiars? and, last, what of ghosts, with beckoning hands and fleeting shapes, which quelled the soldier’s brave heart, and made the murderer disclose to the astonished noon the veiled work of midnight? These which were realities to our fore-fathers, in our wiser age —

— Characterless are grated

To dusty nothing.

— Mary Shelley, “On Ghosts,” London Magazine, 1824

Literary canon in general, and the canon of weird or speculative fiction in particular, is haunted by half-remembered absences. We think we know the details of all of the high points: Frankenstein (1822), The Vampyre (1819), Varney the Vampire (1847), Dracula (1897); the works of Edgar Allen Poe (1809-1849), or Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873). But in reality, we’re just glossing over all the places where we weren’t paying attention: namely, the vast catalogue of stories written by women over the centuries that play a formative role in the creatures and creeping feelings of horror that we take for granted as canonical. An important chapter worth writing in women’s history, and in the history of women writers, is that which considers the particularly feminine perspective that has imagined into existence some of the weirdest works of literature.

For example, there are stranger early modern alternatives to Shakespeare than Virginia Woolf’s portrait of his sister Judith. Margaret Cavendish (1623-1673), Duchess of Newcastle, scientist, philosopher, poet, patron of all things strange, was the first woman to attend a meeting of the Royal Society and get annoyed with Hooke, argue with Hobbes, and raise an eyebrow at Boyle.

In 1666 she published two works together: Observations upon Experimental Philosophy, which argued against the most popular scientific worldview of its time, mechanical philosophy; and The Blazing World, equal parts utopia, social satire, and straight-up weird fiction. It’s a masterpiece of fish-men, talking animals, and submarine warfare—written significantly earlier than Jules Verne, despite including a journey to another world, in a different universe, via the North Pole. Should we not describe his works as Cavendishian? Scholarship more frequently cites Ludvig Holberg’s Niels Klim’s Underground Travels in connection with Verne, although that too bears clear hallmarks of Cavendish’s influence. Cavendish’s dual publication of a work of natural philosophy with a work of speculative fiction have arguably only met their synthesis in the twentieth century, when scientists admit the influence of science fiction in their research, and “hard science fiction” like that of Kim Stanley Robinson has fully blossomed as a sub-genre. In other words, re-conceiving the canon of science fiction, speculative fiction, horror, and weird fiction begins with reconsidering their muddled origins in works like those of Margaret Cavendish, the foremother of so many strange ideas, imagined and real.

The industrious half-beast, half-human characters populating Cavendish’s Blazing World—the bear-men philosophers, the jackdaw-men orators, the spider-men mathematicians—translate the myths, the folk tales, the monstrous births and miraculous occurrences of a declining world of superstition into new centuries, with new narrative possibilities. Alongside their afterlives in the realms of science fiction, their hybrid forms are also a starting point for horror and considerations of the supernatural.

The immovable object of women in speculative fiction is obviously Frankenstein (1818), first imagined two hundred years ago this past June at the famous Villa Diodati. Nobody nowadays really argues with Mary Shelley’s pre-eminent position as the mother of all reanimated corpses. John William Polidori (1795-1821), also present at the first telling of the story, probably features fairly strongly in the role of medical advisor, especially with his experience in the dissection theaters of Edinburgh and considering his academic preoccupations. Taking the staples of weird, speculative, horrifying, and supernatural fiction as a whole, most of the major tropes were the product of female authorship. Frankenstein’s Monster—scientific aberration, stitched-up King Zombie, vengeful revenant—is only one such pillar: a hybrid in the style of Cavendish’s Blazing World, yet a ghost in his own right, ruthlessly haunting his creator.

And ghost stories too have a place in women’s history: Elizabeth Boyd’s Altamira’s Ghost (1744) describes a disputed succession adjudicated over by a spirit. Although supernatural in content, it is essentially a commentary on social injustice narrated by a ghost and dealing with the famous Annesley succession case, in which an orphan’s inheritance rested upon proof of his legitimacy. One peculiarity of the case is that a maidservant named Heath, claiming James Annesley illegitimate, was found guilty of perjury on one occasion, then acquitted on another, effectively allowing James to be ruled both bastard and not bastard simultaneously. Boyd was primarily a paid “hack” of notable skill, but it should be mentioned that her openly supernatural works (“William and Catherine, or The Fair Spectre” (1745) being another) fall thematically into the fantastically interesting category of female apparition narrative, in which female ghosts appear in order to provide insight into male wrongdoing and most notably domestic violence. A ghost woman can talk about things a live woman may not, and thus assist in the administration of justice. At one time an accepted literary device in its own right, this seems to have been forgotten along with Boyd and her contemporaries.

The pattern has a tendency to repeat. But the women of nineteenth-century weird fiction after Mary Shelley were more interested in giving their ghosts a body, much like the monster of Dr. Frankenstein. In 1828, only ten years after Frankenstein, Jane Loudon produced The Mummy! Or A Tale of The Twenty-Second Century (published by the piratical Henry Colburn, who published Polidori’s Vampyre under Byron’s name in 1819). Both of Loudon’s parents were dead by 1824, when she was 17, and she was forced to find some way to “do something for [her] support”:

I had written a strange, wild novel, called the Mummy, in which I had laid the scene in the twenty-second century, and attempted to predict the state of improvement to which this country might possibly arrive.

Already well-traveled and with several languages under her belt, Jane Loudon was clearly not without either smarts or skills. Her husband-to-be sought her out after writing a favorable review of the novel, believing her, naturally, to be a man. Once the shock of her femininity had worn off, they were married a year later.

Loudon’s resurrected Cheops is a sage and helpful corpse, granted life maintained by a higher power rather than by human error and hubris. Loudon’s twenty-second century is an absolutely blinding bit of fictional prophecy, on par with William Gibson’s Neuromancer for edgy prescience. The habit of the time was to view the future as the early nineteenth century, but with bigger buildings and with the French in charge, but Loudon’s 2126 AD goes for women striding about independently in trousers, robot doctors and solicitors, and something that’s not too far from an early concept of the internet. Her strange, wild story, in which corpsified Cheops helps rebuild a corrupt society, addresses much of the underlying horror of Shelley’s Frankenstein with a more redemptive take on the reanimation of dead flesh. It was also a definite influence on Bram Stoker’s better-remembered “Jewel of The Seven Stars,” published in the 1890s, and possibly even on Poe’s “Ligeia” in 1838, in which a man painstakingly wraps his dead wife in bandages prior to her burial.

There’s an argument for suggesting that writing weird fiction, at least in the form of ghost stories, became something of a fashionable exploit for nineteenth-century ladies. The Countess of Blessington (“A Ghost Story,” 1846), Mrs. Hofland (“The Regretted Ghost,” published in The Keepsake in the mid-1820s) are just two examples. On one hand, they might be seen as a natural evolution of the legacy of the Gothic giants Clara Reeve and Ann Radcliffe, alongside Jane Crofts’ hugely successful (and frequently necessarily anonymous) forays into the profitable world of Gothic novels and chapbooks (“The History of Jenny Spinner, The Hertfordshire Ghost,” 1800) and C.D. Haynes (“Eleanor, Or The Spectre of St. Michaels,” 1821). On the other, there is something innately rebellious, hinting at manifest destiny, in the feminine colonization of weird fiction as a form in which women can express themselves.

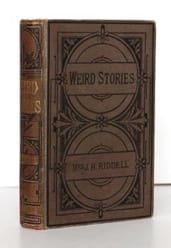

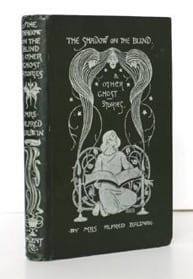

Women who were already making a living as authors of anonymous romances and social sketches bent their efforts to the weird and supernatural with no apparent intent of turning a profit, but apparently more as an endorsement of the genre as something inherently theirs. Mrs. Riddell, Mrs. Oliphant, the Countess of Munster and Mrs. Alfred Baldwin were all successful, comfortable women with no particular need to deviate from a working formula, but they all ventured into what they clearly considered a darkness to which they had a right, and produced some of the very best weird stories of the nineteenth century.

Women who were already making a living as authors of anonymous romances and social sketches bent their efforts to the weird and supernatural with no apparent intent of turning a profit, but apparently more as an endorsement of the genre as something inherently theirs. Mrs. Riddell, Mrs. Oliphant, the Countess of Munster and Mrs. Alfred Baldwin were all successful, comfortable women with no particular need to deviate from a working formula, but they all ventured into what they clearly considered a darkness to which they had a right, and produced some of the very best weird stories of the nineteenth century.

Mrs. Riddell’s (1832-1906) Weird Stories, published by Hogg in 1882, is one of the rarest and most beautifully written collections of supernatural stories of the last two hundred years.

Mrs. Riddell’s (1832-1906) Weird Stories, published by Hogg in 1882, is one of the rarest and most beautifully written collections of supernatural stories of the last two hundred years.

Mrs. Margaret Oliphant (1828-1897) wrote an incredible body of work—numbering over 120 published novels, historical works and collections of short stories—from the 1840s until the late 1890s, spanning almost the entire Victorian age in all its manifold weirdness.

Mrs. Margaret Oliphant (1828-1897) wrote an incredible body of work—numbering over 120 published novels, historical works and collections of short stories—from the 1840s until the late 1890s, spanning almost the entire Victorian age in all its manifold weirdness.

The Countess of Munster, Wilhelmina FitzClarence (1830-1906), Scottish peer and illegitimate granddaughter of William IV, only became a novelist later in life. She published her Ghostly Stories in 1896, displaying a tremendous talent for the weird.

Florence Marryat’s (1833-1899) The Blood of The Vampire, published the same year as Stoker’s Dracula and now shamefully almost forgotten, is a nuanced and complex (albeit erratic in execution) look at nineteenth-century male-dominated societal norms, race, sexuality, gender, and xenophobia, couched in the terms of the supernatural. Its mixed-race heroine is exploited by men and rejected by other women; the fact that she might be infected with vampirism is a secondary (and never  actually resolved) possibility when placed alongside how she is treated, regardless of supernatural influence. Marryat wrote over seventy published works, toured with the D’Oyly Carte company, had her own successful one woman show, ran lecture tours preaching female emancipation, and, during the 1890s, ran a women’s school of journalism.

actually resolved) possibility when placed alongside how she is treated, regardless of supernatural influence. Marryat wrote over seventy published works, toured with the D’Oyly Carte company, had her own successful one woman show, ran lecture tours preaching female emancipation, and, during the 1890s, ran a women’s school of journalism.

It’s almost inconceivable that the “stuff of extrapolation” has preserved Klim, Polidori, Stoker, Le Fanu, Rymer and their legions of successful cohorts as the manifest summits of weird fiction in the nineteenth century, and yet rarely even mentions Jane Loudon, Mrs. Riddell, or even Mrs. Oliphant, who had a body of work larger than that of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Mary Shelley’s 1824 essay “On Ghosts,” which began this post, had at its heart two main questions: “What have we left to dream about?” and “[I]s it true that we do not believe in ghosts?” The catalogue of weird fiction produced by Shelley and those after her shows that women had a great deal left to dream about. Female weird fiction frequently deals with minorities and outliers: wronged gypsy women, beaten wives, revenant witches, overly prescient children, the occasional voodoo priestess, and a preoccupation with the righting of wrongs, the application of a certain balancing justice. Unlike in the masculine variants, the menaces and threats are more often laid to rest or propitiated, or indeed left to float off on an ice floe—rather than being chopped up, burned up, stabbed up, or staked up by a gang of bros armored by either science or God, the two being interchangeable when fighting darkness.

One thing is for certain: the influence of women writers, whether anonymously, writing under male pseudonyms, or under their own names upon the landscape of the weird is not only significant, but momentous. If one can identify a trope or a device, the chances are that if one goes back far enough it originated somewhere in the untended and rarely-visited forest of female writers of the irresistibly odd and disturbing. As for Shelley’s second question, it is now their ghosts which haunt literary history and which must be remembered. Yet to believe them, requires that they be seen.

Jonathan Kearns has been working in the book trade for over twenty years and is the proprietor of Jonathan Kearns Rare Books & Curiosities. He is also a faculty member at the York Antiquarian Book Seminar.

May 21, 2017 at 4:30 am

Reblogged this on IBHE Collaborative University.