by guest contributor Hannah Malcolm

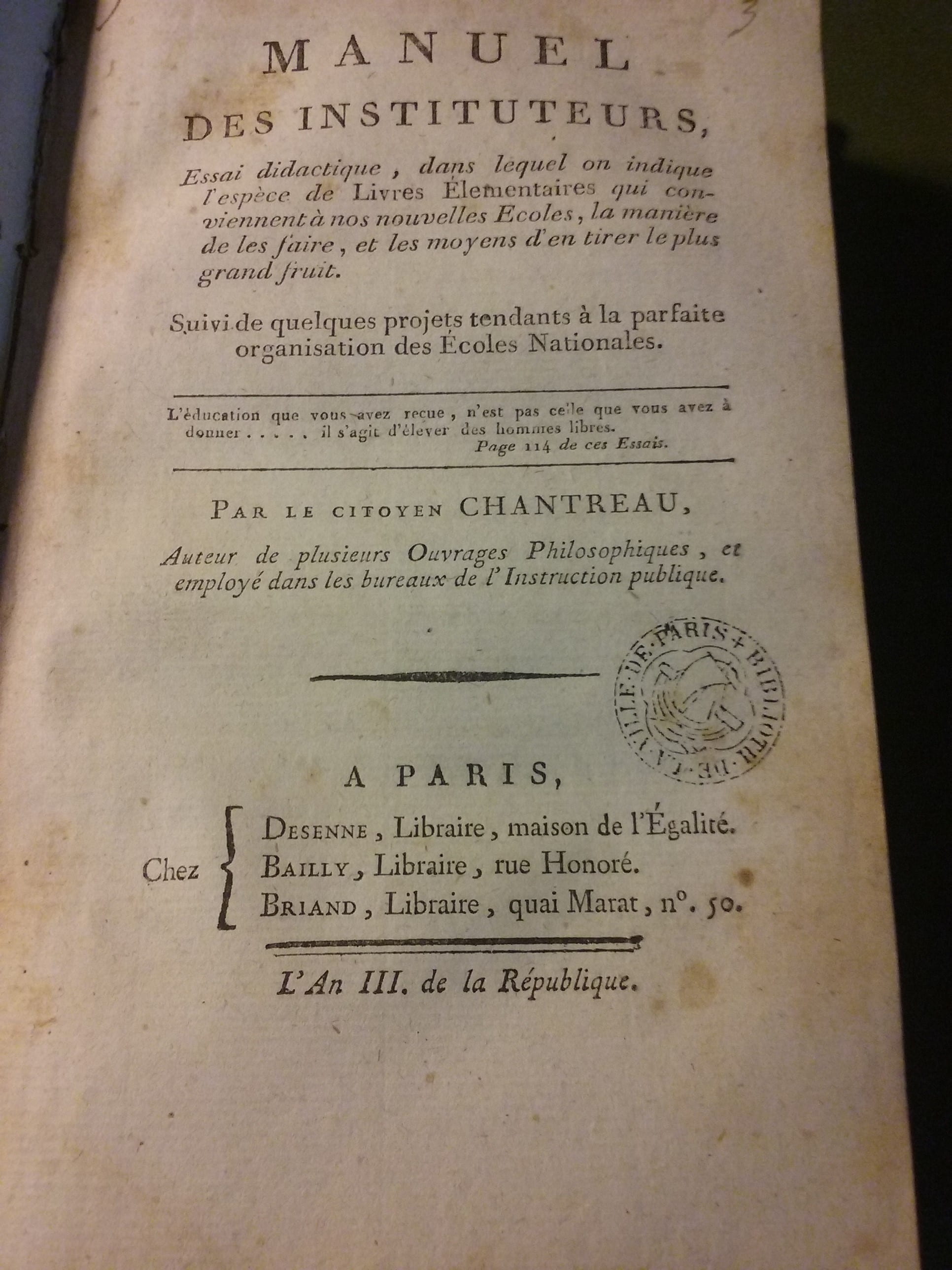

Most of these new textbooks were bound and were often tiny enough to fit in a child’s pocket. Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris.

During the French Revolution, statesmen faced the task of altering society in order to preserve the new Republic, which entailed developing a politics of virtue and culture. In response to demands for public involvement in government, the revolutionary assemblies published all laws and speeches in newspapers. However, given the novelty of representative politics, the government felt that simply making the new legal system widely available was not enough to enlighten public opinion. Specifically, the revolutionaries feared that prejudices left from the ancien régime would taint public opinion and individual judgment.

This strong distrust of prejudices had notable philosophical roots. In his Encylopédie article on judgment, Louis de Jaucourt began by stating that judgment should not be confused with knowledge that is acquired solely through the senses. Instead, “judgment is […] an operation of the reasonable soul; it is an act of research.” Similarly, in Le dictionaire universel, Antoine Furetière defined judgment as a “power of the soul” which has the capacity to “discern the good from the bad, the true from the false.” However, Furetière differs from Jaucourt by extending his definition to include “opinions of wise people” as well. In this sense, judgment can be the result of a personal trait, rather than defined strictly as a process. Furetière also includes definitions of préjugés, prejudgments or prejudices, as a preoccupation with an opinion that one has conceived; Jaucourt defined them as “false judgments of the soul.” These imprecise conceptions illustrate the uncertain nature of morality and politics at the time. Despite these subjective definitions, the revolutionaries believed that incomplete processes of judgment could be identified through their propensity to mislead the public. Because of this risk, the revolutionaries needed to actively educate the population, and they explicitly spoke of this mission in terms of public safety. People argued that without an educational system, the new generation would either be unable to continue the republic or, at the very least, they would continue to endure crises. The Committee of Public Instruction intended to establish a national school system to enlighten the public on the benefits of the Republic and their new role as citizens.

On the last page of the announcement for the textbook competition, the Committee again emphasized the importance of education in defeating prejudices. Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris.

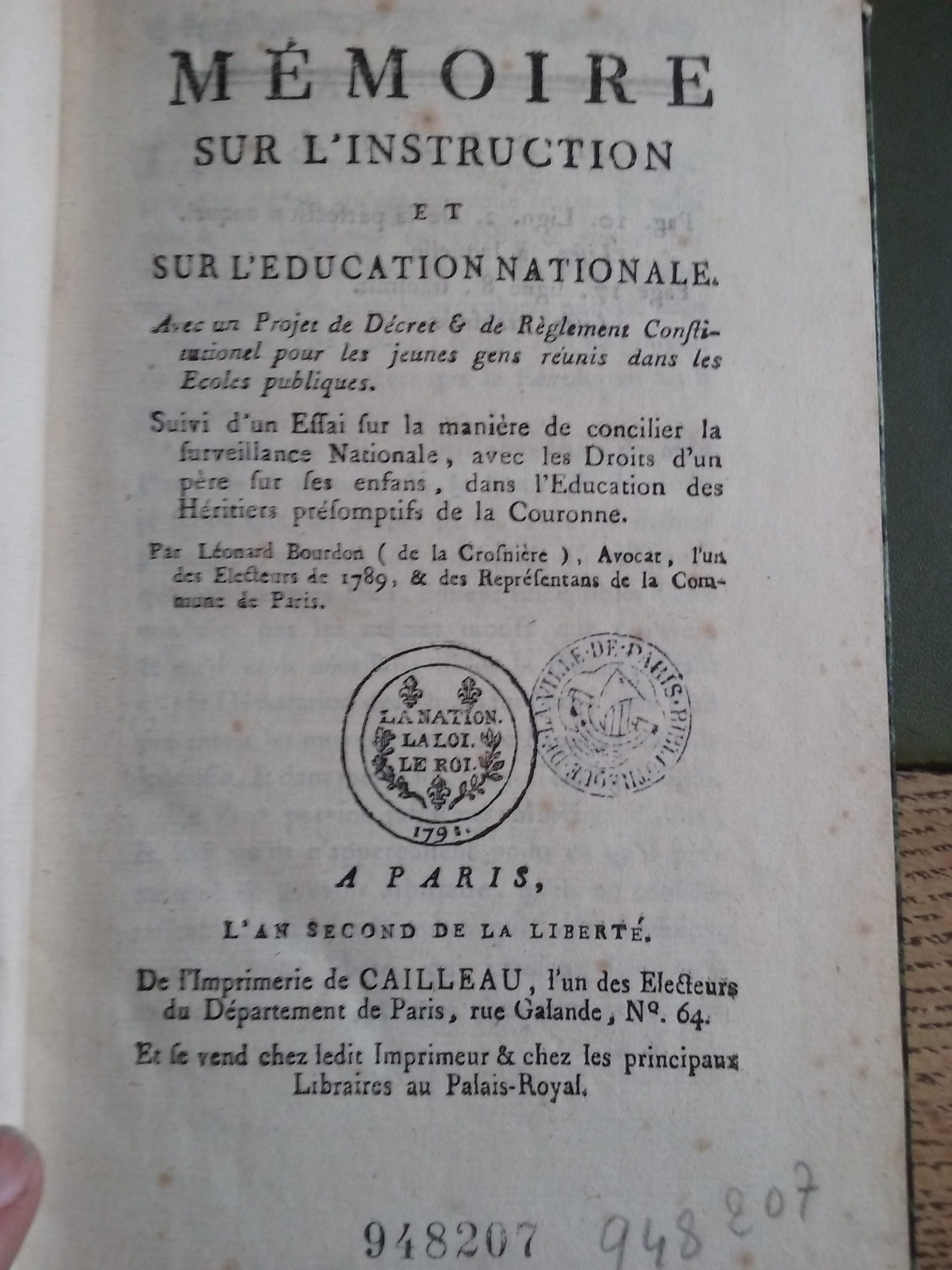

Therefore, in Year II of the revolutionary calendar, the Committee of Public Instruction announced a contest for new elementary textbooks. Among the many goals listed was encouraging students to abandon ignorance and prejudices. The procès-verbaux of the Committee indicate that many of the textbooks analyzed here were submitted to and reviewed by the Committee. These new textbooks consistently warned against the danger of prejudices. A book of weekly moral lessons declared that “prejudices are the tyrants of the soul.” Prejudices, under this understanding, encouraged one to act and think like a tyrant. This pithy phrase linked disavowal of prejudices to the commonly encouraged hatred of tyrants and suggested that that the latter would compel one to reject all influences of prejudices. In his textbook, François-Xavier Lanthenas argued that “The education which existed under the ancien régime […] was calculated […] to entrench prejudices.” They were clearly seen as corrupting vices which must be eradicated. Revolutionaries believed that this could best be accomplished through a national form of education and instruction, as summed up by Léonard Bourdon de la Crosnière’s statement that “instruction is the friend and companion of liberty and the most formidable scourge of despotism,” whereas France’s “enemies count on the ignorance of the people.” By providing access to knowledge, education would give students resources to attempt to discover truth.

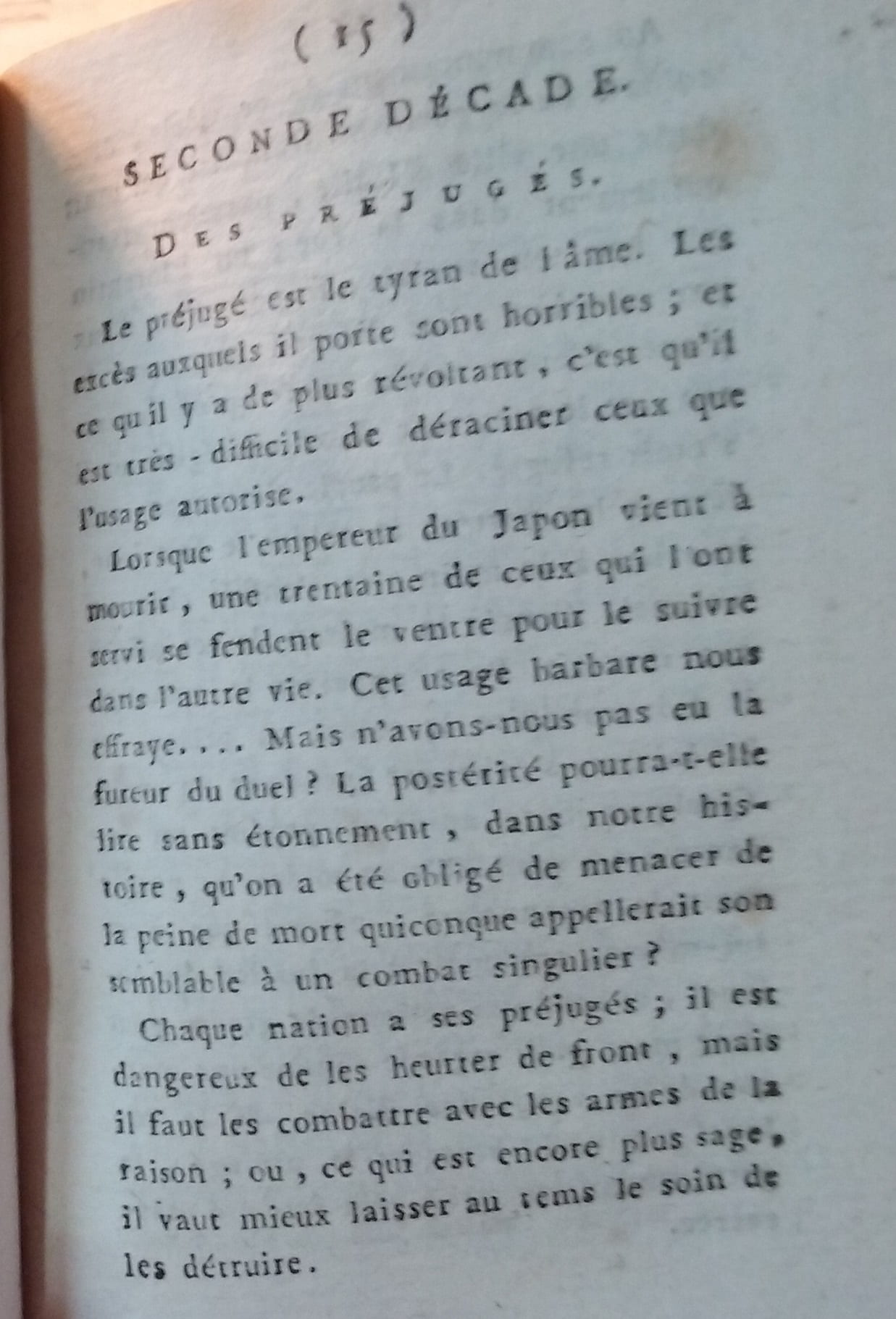

Warning about the danger of prejudices. Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris.

By focusing their educational projects around the issue of judgment, the revolutionaries emphasized the centrality of rationality to their conception of society while also revealing their fears about the negative qualities of humanity. As Bourdon de la Crosnière phrased it in his pamphlet, the new education plans must “convert schools from prejudices, from ignorance, and from servitude into schools in which free, virtuous, and enlightened men are formed.” Yet the fear remained that individuals would not want to be educated. Lack of cooperation from the public could cripple the plans for public instruction, as education “depends a lot on the reciprocal will of the people who contribute to giving and receiving it.” Without this reciprocal desire for education, the moral faculties of the students will be destroyed. Revolutionaries saw the continuing prevalence of prejudices as evidence that people might not always be—or even want to be—rational. This voluntary irrationality exhibited itself in the various revolts throughout France, but particularly in the Vendée. Nevertheless, the revolutionaries maintained belief that education held the potential to perfect humanity. In his Manuel des Instituteurs, Pierre-Nicolas Chantreau emphasized that the primary goal of public instruction was to ensure that future generations would have neither the prejudices of the contemporary ones nor the inclination to form new ones. Destroying prejudices through education was seen as a way to guarantee the survival of the new Republic.

Textbooks meant for teachers, or pamphlets for the public, tended to be unbound folded sheets of paper tucked into one another. Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris.

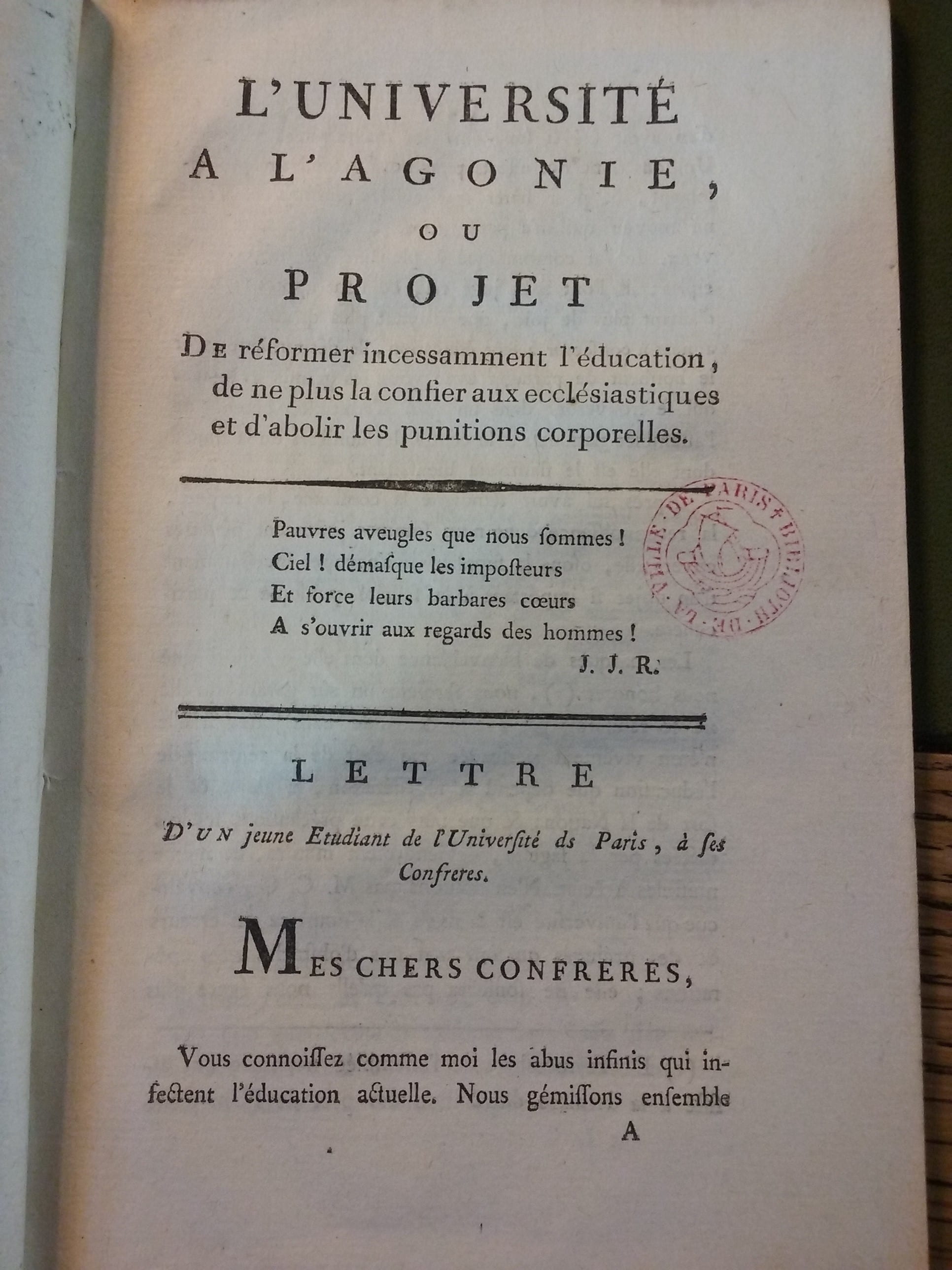

However, the continued delay from the Committee of Public Instruction to establish a school system led to a flurry of pamphlets and letters suggesting new structures or ways to provide education in the interim. Some of these letters suggested that training for law should encourage judgment, but the authors also worried that most students would not continue their education that far; one catechism taught students that all people were judges for the government. The pamphlets identified prejudices as one of the main problems in education—second only to the aforementioned governmental delay. In a pamphlet entitled L’université à l’agonie, Desramser, a university student, emphasized the necessity of making sure teachers “will no longer prefer their personal interests, tyrannical prejudices, or dangerous vices.” Prejudices, it was argued, stopped people from considering other points of view and therefore made it more difficult to reach political compromises. Returning to the conception of judgment as a process, Jaucourt allowed for the possibility of two judging individuals to come to different conclusions. Likewise, Bourdon de la Crosnière argued that if students do not learn to reflect on ideas that they disagree with, then they will be unable to form judgments. It is this reflection on abstract and dissenting ideas that separates judgment from mere reason. However, other articles in the Encylopédie made it clear that tolerance of dissent was founded on the belief that with time and proper education, all rational beings would, through use of judgment, come to the correct consensus.

‘The University in Agony’ by Desrasmer, student at the University of Paris. Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris.

The revolutionaries’ full-frontal assault on prejudices was not condoned by the conservatives of the time, even aside from the implication that religion qualified as a complex of superstitious prejudices. In his Reflections on the Revolution in France, Edmund Burke alluded to the revolutionary project to remove all prejudices from society and stated that the revolutionaries were rashly constructing “a scheme of society on new principles” and disregarding “the judgment of the human race.” What the revolutionaries saw as prejudices, Burke saw as “common judgment,” and he warned that abandoning it would lead to social chaos, as he saw this common judgment to be the result of previous generations’ wise decisions and necessary to social stability. When the revolution labeled these beliefs as prejudices, they claimed that they were irrational and not even based on experience. Therefore, they were able to frame them as hindrances to true judgment and dangerous to society and the political process.

This hesitation towards accepting a multiplicity of accurate outcomes is likely due to the moral and social qualities of judgment. One textbook author, Nanydre, argued that the public could not blame people for their mistakes if they are only based on prejudices and not from malicious intent. Without access to education, people might be unable to ignore their prejudices. However, as time passes, people would have more evidence needed to abandon their mistaken prejudices. Only after they have ignored opportunities for reform could they be then faulted for failing to learn. Although the Revolution rejected traditional Christianity, it did not intend to abandon morality. Public instruction was not merely the transmission of knowledge but also the instilling of virtue into citizens. The moral guidelines transmitted through education would prepare students to make proper decisions as citizens. Jean Chevret argued that inculcating civic virtues was no different than lessons in honesty. The revolutionaries thus sidestepped the issue of whether morals should be considered prejudices and instead only focused on those prejudices which they deemed dangerous to the new society.

Léonard Bourdon de la Crosnière’s pamphlet on public instruction. Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris.

Despite this public engagement, the threat of prejudices led the Committee on Public Instruction to devote most of its time to educating the public, rather than focusing solely on children. Therefore, instead of instituting a national system of public instruction, it organized festivals, commissioned artworks commemorating revolutionary martyrs, established a new calendar, and otherwise reorganized society to make it inhospitable to prejudices. This change of direction was crucial as few schools outside of Paris accepted the new textbooks. The Committee’s incomplete work is unsurprising, given not only the short life of the First Republic, but also virtually every education system’s inability to completely eradicate prejudices from society.

Hannah Malcolm is an undergraduate at Appalachian State University. She is writing an honors thesis on public instruction during the French Revolution.

1 Pingback