by guest contributor Anna Toledano

Autobiography is an art form that only few have mastered. The newly reopened permanent exhibition at the Musée de l’Homme (Museum of Mankind) in Paris does a remarkable job of writing the book on our entire species. The museum tells the tale of what makes humanity unique through universal themes such as reproduction, death, and language using its rich collections, which featured in both the storied, racist Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro (1882–1936) and the first iteration of the Musée de l’Homme opened in 1938. The curators are sensitive to equity among different cultural groups and the breadth of the human experience, although the interpretation suffers from a tinge of human exceptionalism.

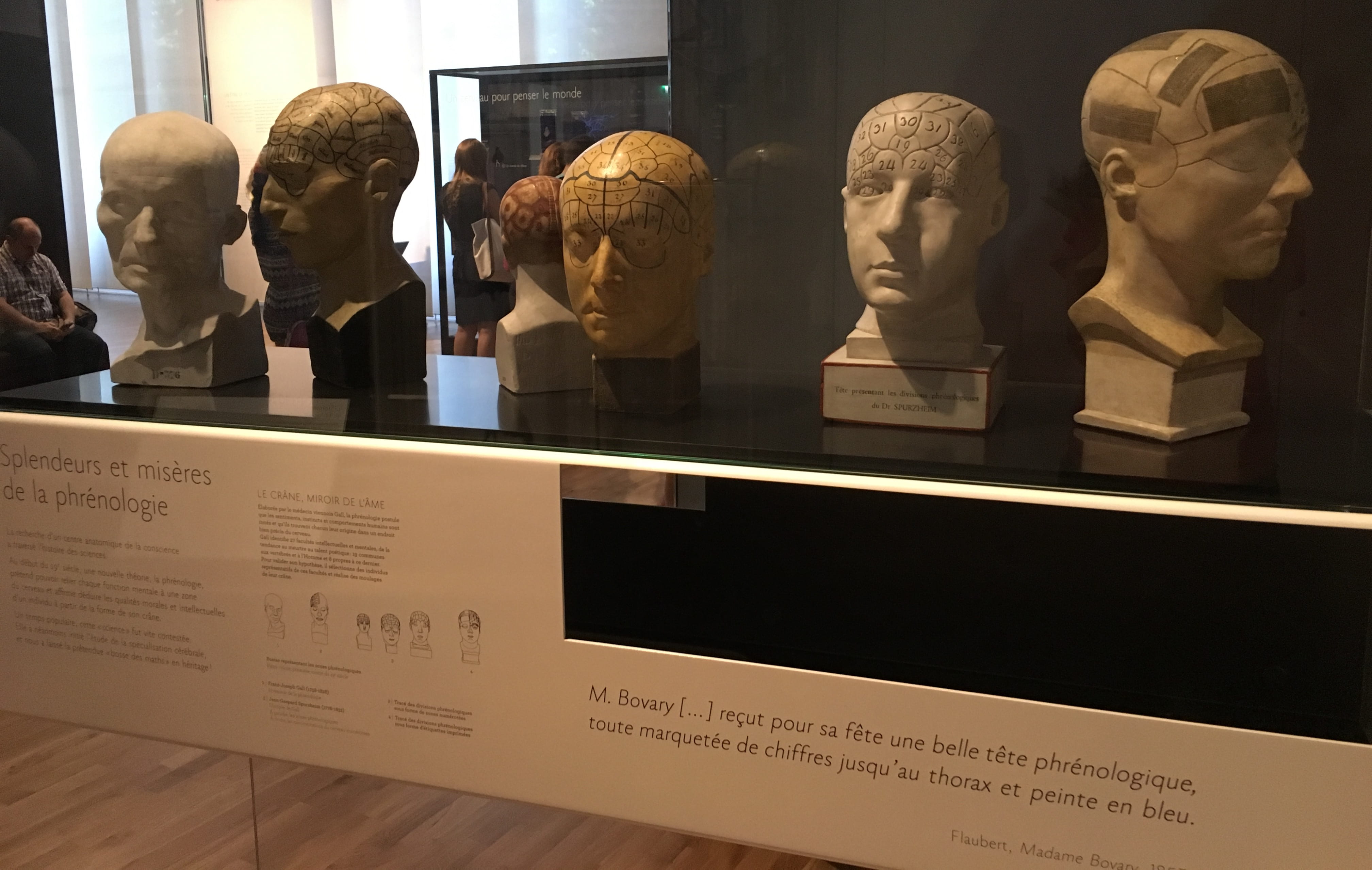

Phrenological busts repurposed to show the failings of such methodology (author photo)

Alice L. Conklin deftly describes in her book In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850–1950 (Cornell, 2013) the role that the historic museum played in the establishment of traditional French colonial, racist anthropology. See Alice L. Conklin’s and Christine Laurière’s essays in the museum catalog for a more in-depth look at the historical context for the reimagined permanent exhibition. While the social missteps of the former institution are carefully avoided today, the message of the modern museum is strongly tied to its historical legacy. (Consider the repurposing of busts that once spread the edicts of phrenology: today curators use them to show that such methodology is not science.) This legacy is characterized by the words of Paul Rivet, the glorified father of the museum, that “Humanity is one and indivisible, not only in terms of space, but also in terms of time.” The challenge to make culture timeless, but not frozen in time is one that all anthropological museums face. The museum in Paris tackles the additional challenge of showing that it is no longer frozen in time either.

Objects from the historical collections feature in displays (author photo)

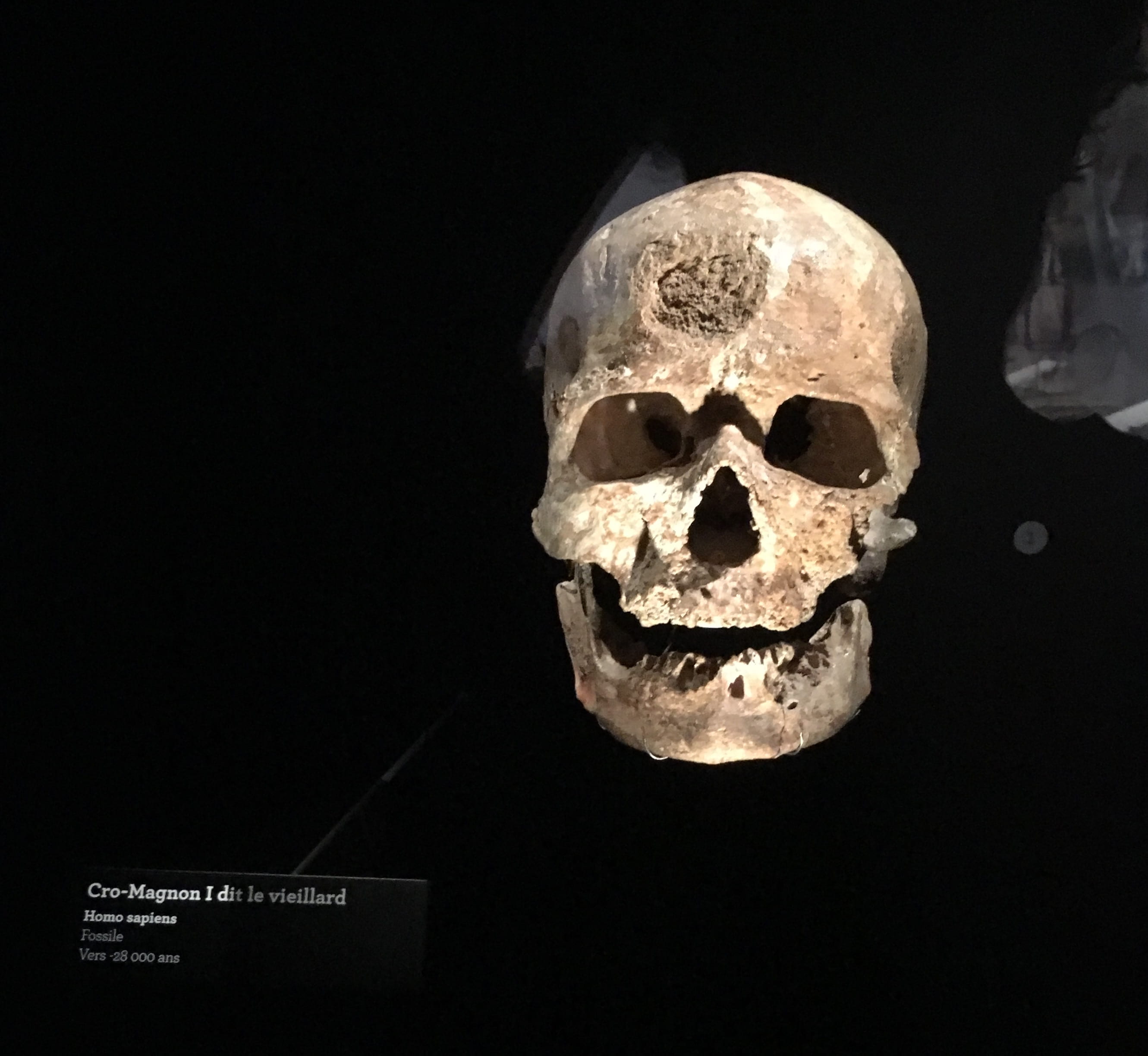

The curators structure our collective biography in the Galerie de l’Homme into three parts: “Who are we?” “Where do we come from?” “Where are we going?” This chronological narrative leads visitors through displays featuring pieces from the historic collection, such as skeletons and ceremonial clothing, as well as model reconstructions of classic sites such as the footsteps at Laetoli. The strength of the exhibitry comes not from the well-done model of a half-eaten mammoth, but from the objects from the original collection. The historic medical moulages are a highlight, although the objects are placed in darkened kiosks (perhaps due to both preservation concerns and shock value). The real fossil skulls of our evolutionary ancestors excavated in the rich caves of France are breathtaking. The inclusion of animal specimens from the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle gives context to the place of humans within the history of evolution. This 2015 renovation is part of a larger set of relatively recent overhauls of permanent exhibitions at the MNHN; the Musée de l’Homme has been associated with the MNHN since the early twentieth century. A feature on domestication and our bond with dogs is heartwarming, but the principal focus on hunting only elevates our position relative to the other creatures on display.

A separate viewing experience for historic medical moulages (author photo)

Real skulls from our ancestors, such as Cro-Magnon man, excavated in France are a highlight (author photo)

The museum embodies its commitment to include all peoples not only within its narrative but also in the experience of the exhibition. A visually arresting wall of tongues, which visitors can pull to hear snippets of little-spoken languages from across the globe, caters to auditory learners. This section on linguistics is well-conceived in its emphasis on diversity as well as the intersectionality of multiple cultural identities, such as being an American and a Yiddish speaker. Videos for visual learners feature experts discussing how terminology matters, especially with regard to vestiges of colonialism. Through this lens, it is interesting that the majority of interpretation is only available in French. The main signage, as well as some audio testimony, is trilingual—French, English, and Spanish—but that is not the majority.

Visitors experience sounds of little-known languages from around the world by giving each tongue a yank (author photo)

Touch screens with which visitors can call up a high-resolution photo as well as provenance information about any object in the richly filled cases are a victory for useful museum technology. The interactive label format is perfectly suited to the exhibitry. The options for English and Spanish are grayed out here, indicating the intention to add them, but for the moment they are noticeably lacking. The curators make a nod to accessibility by offering French Sign Language, but its purpose is unclear since all of the interpretation is communicated textually here.

The theme of intersectionality—critical to our modern understanding of culture—is happily at the forefront of the discussion upstairs of our future. Visitors play a globalization game on a touch table, matching photos of things like sushi to their place of origin (the California roll matches to the American West). Sensory learners can enjoy the scents of dishes of cuisines from the world over that all feature rice (but, in this visitor’s opinion, the synthetic smells weren’t all that appetizing).

A digital label, complete with a fantastic photo and a full description of the featured object (author photo)

Our interconnectedness comes to the fore at the end of the exhibit hall, where curators urge us to save our common planet in light of ever-pressing natural resource conservation and biodiversity crises. The success of our future is not one devoid of technology, though. We evolve alongside medical technologies such as antibiotics and artificial limbs, which the museum frames as a positive outcome. In a final interactive feature, visitors are invited to imagine the future of the human race in a photo booth; their videos are added to an ever-changing smart wall. The new participatory museum model, the future of audience-curated content in museum education, is structurally a perfect way to show our future.

In Chris Marker’s 1962 science fiction dystopian short film, La Jetée (The Jetty), the original Musée de l’Homme serves as the unchanging location to which Marker’s time traveler returns. The museum, filled with ageless specimens, is frozen and timeless. While the new Galerie de l’Homme honors this legacy, it stresses that time marches on and acknowledges that we are a living, breathing, changing species, much like the museum itself.

Anna Toledano is pursuing a PhD in history of science at Stanford University. A museum professional by training, her research focuses on natural history collecting in early modern Spain. Follow her on Twitter at @annatoledano.

Leave a Reply