By Jan Stöckmann

On 16 January 1926, a group of statesmen, diplomats, and civil servants gathered in Paris to celebrate the inauguration of the International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation at its grand premises in the Palais Royal. Wine was served, an orchestra played Beethoven, Handel, and Mozart. French education minister Edouard Daladier addressed the guests, outlining the idea behind the Institute: “Just like the League of Nations itself,” Daladier explained, “the Institute was inspired by collaboration for peace” (Program Leaflet, January 1926, A.I.6, IIIC Records, AG 1, UNESCO Archives, Paris). It was intended as a platform of exchange for academics, writers, teachers, and artists, to encourage common standards in science and librarianship, to spread major scholarly achievements, to protect intellectual property, and to facilitate student exchanges. Daladier’s address culminated in the proclamation that “the future of the League of Nations depended on the formation of a universal spirit.” In other words, building peace in the minds of people would guarantee peace at large—a variation of which remains UNESCO’s slogan to this day.

The Institute was the executive agency of the Geneva-based International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, founded in 1922 at the League of Nations. The Committee boasted a dozen public intellectuals, including Marie Curie and Albert Einstein, who met annually to demonstrate the trans-nationality of science and culture. Since, however, the League was unable to provide sufficient funding, the Committee was little more than an illustrious meeting of international intelligentsia at the Palais des Nations. When the Committee expressed its dissatisfaction with this state of affairs, the French government responded in 1924 with a generous offer—the only condition being that the new Institute be located in Paris: “The French government would be disposed to found in Paris an International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation…. All the costs would be covered by an annual subsidy” (Le Gouvernement français serait disposé à fonder à Paris un Institut international de coopération intellectuelle […] Tous les frais seraient couverts par une subvention annuelle. Communiqué, 12 September 1924, A.64.1924.XII, IIIC Records, AG 1, UNESCO Archives, Paris).

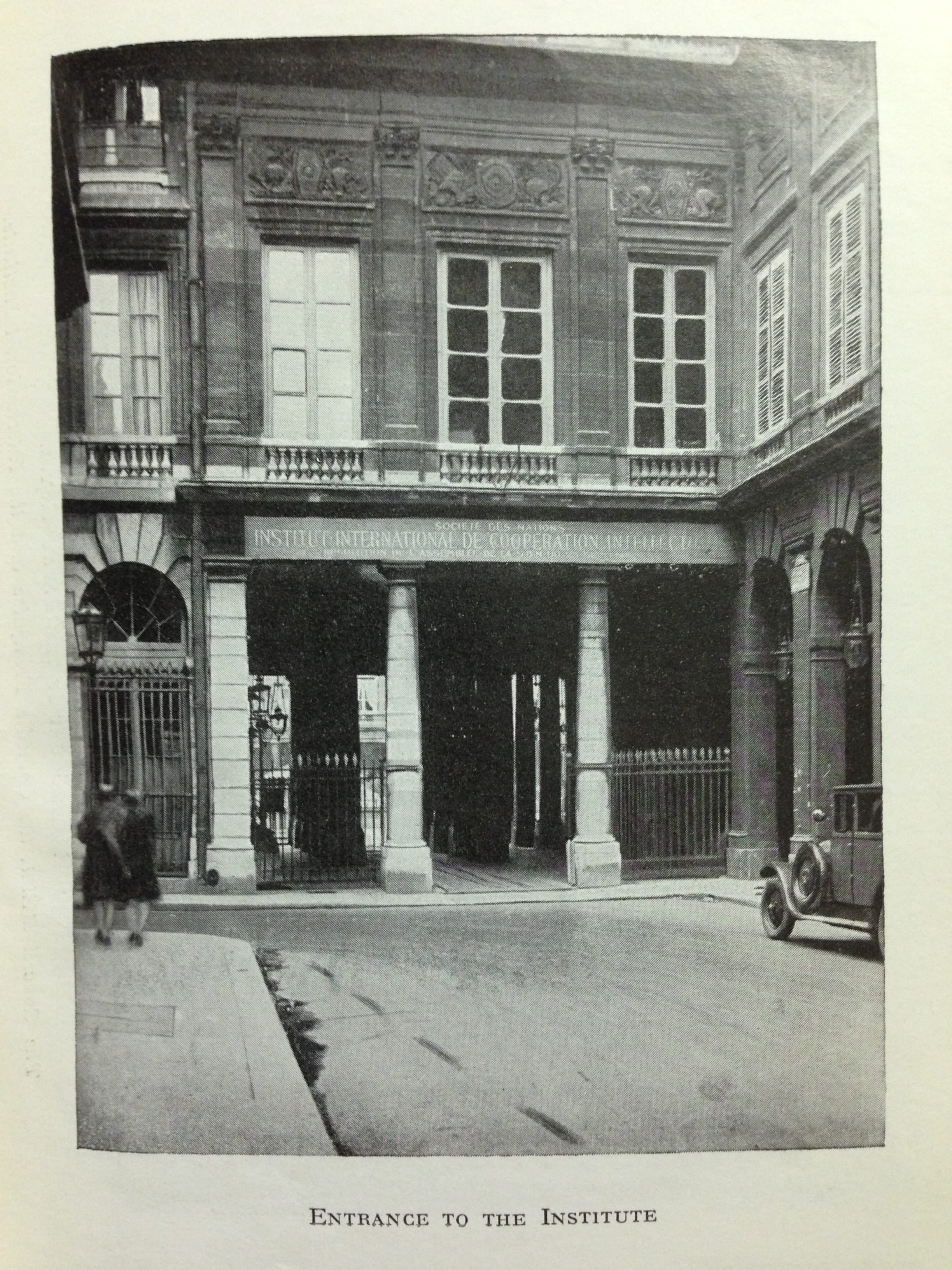

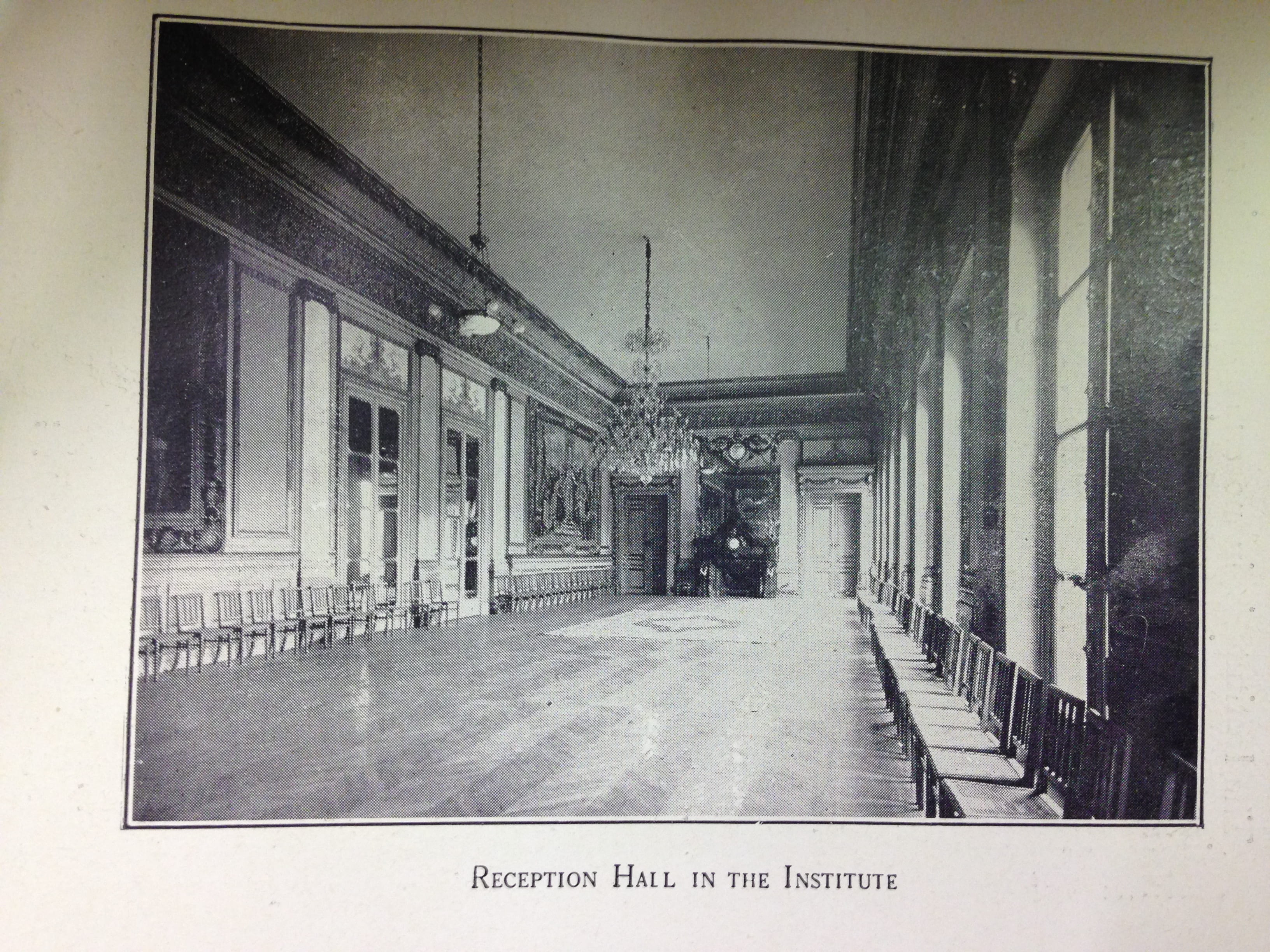

The League of Nations gratefully accepted. After approval by all authorities, the Institute opened the following year. Thanks to the French endowment, its home became the Palais Royal in central Paris. Situated conveniently close to the French Education Ministry, the Palais Royal provided the Institute with outstanding facilities for meetings, receptions, and research work. It spread over four floors, including a conference room, reception salons, a library, an archive, various offices, and a dining room. The Institute fully refurbished the premises and fitted them with a modern kitchen, an intercom system, fire extinguishers, and linoleum floors, spending a total of 184,877 francs. League Secretary-General Sir Eric Drummond commented upon the luxurious setting of the Institute in his speech at the opening ceremony: “There is one thing that I envy, namely the magnificent building which today is formally placed at the Institute’s disposal by you, Monsieur le Président. In this respect, I fear that the Secrétariat must accept to remain for ever in a position of inferiority” (Address by Eric Drummond, 16 January 1926, A.I.6, AG 1, IIIC Records, UNESCO Archives, Paris).

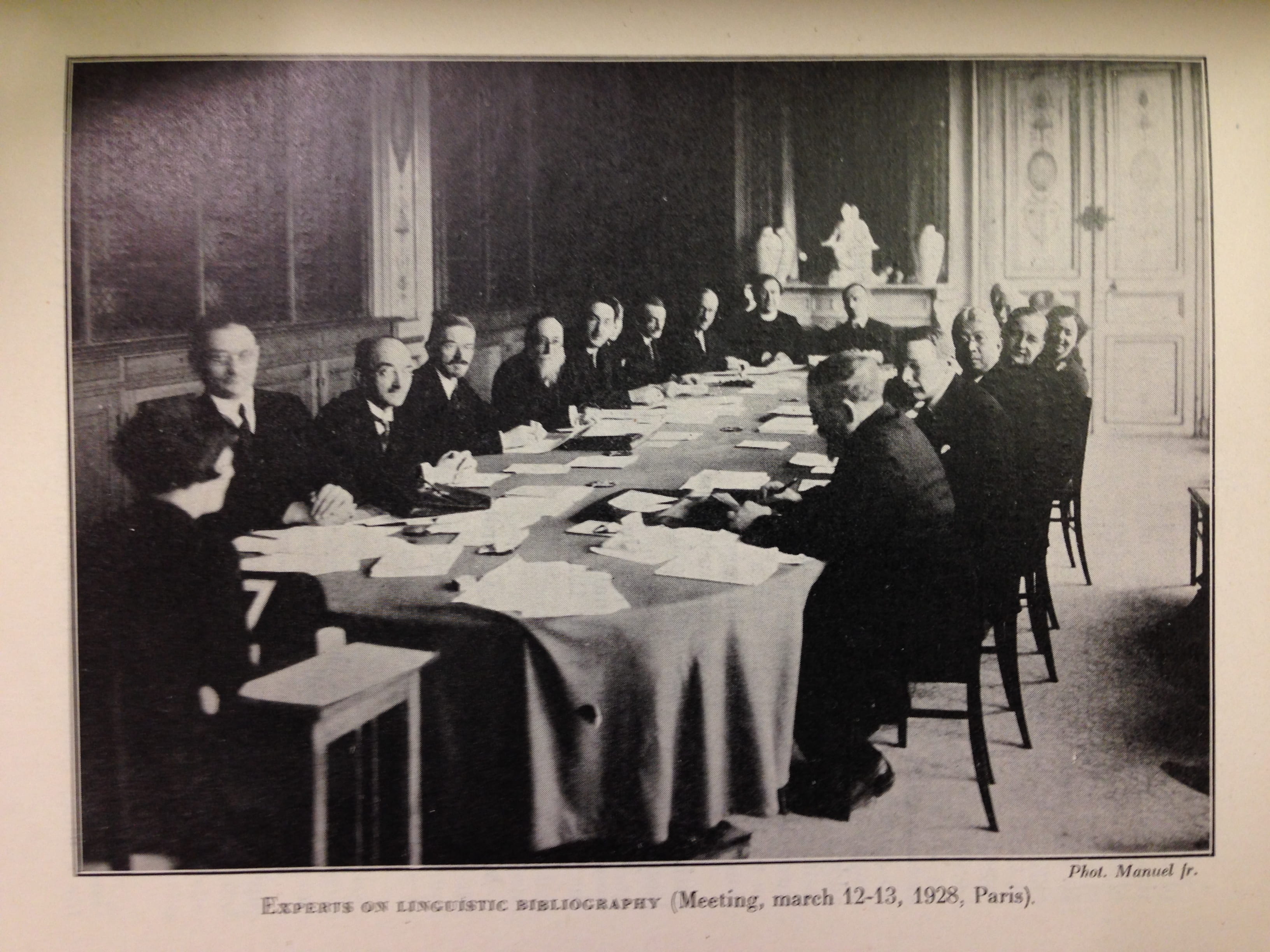

The Institute, directed from 1926 until 1930 by French education expert Julien Luchaire, started out with an ambitious program: a section for university relations, one section devoted to natural sciences and one to humanities, a legal service, and an information bureau which published leaflets, bulletins, and handbooks. The diverse range of projects included the revision of school textbooks, the spread of radio and cinema productions, an agreement on intellectual property rights (passed in 1938), collaborations between artists and museums (including the publication of the quarterly review Museion), and the organization of scientific conferences—such as the International Studies Conference, the world’s first association for the study of international relations. Most endeavors enjoyed only mild success, as the Institute lacked funds to do more than facilitating networks between existing institutions. During the 1930s, the Institute’s ideal for peaceful cooperation suffered from the withdrawal of the dictatorships from all League activities, and in 1940 the German authorities put its offices under seal. A brief attempt after the Second World War to revive the Institute failed, and instead Jean-Jacques Mayoux, the Institute’s last director, signed a contract with Julian Huxley which transferred all property to the newly established UNESCO—thus ending its short, twenty-year history.

Despite its shortcomings, the Institute provided an important site for intellectual debates and cultural exchange during the inter-war period. A particular gem is the series of conversations between leading intellectuals, including a correspondence between Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud called Why War? (1932). The Institute’s underlying idea as well as its various projects anticipated in many ways the work of post-1945 international organizations. It is surprising, therefore, that intellectual cooperation under the League of Nations remains such an understudied field, with only a handful of articles (such as Daniel Laqua’s “Transnational intellectual cooperation, the League of Nations, and the problem of order” in the Journal of Global History) and only one recent monograph, Jean-Jacques Renoliet’s L’UNESCO oubliée: l’Organisation de Coopération Intellectuelle (1921-1946), published in 1999 but only available in French. Almost a century later, it is a good time to reflect upon the achievements of inter-war intellectual cooperation, and to make use of the Institute’s archives hosted with UNESCO in Paris. So this blog post is as much celebrating a birthday as it is urging not to forget the dead.

Jan Stöckmann is a doctoral candidate in History at New College, Oxford, and currently a visiting PhD student at Columbia University, New York. His dissertation explores networks of scholars, diplomats and politicians who promoted the study of International Relations as an academic discipline from about 1914 to 1939. Besides his research, he has spent two months at UNESCO as an intern.

Leave a Reply