by guest contributor Daniel Joslyn

In his most famous speech, “Self-Made Men,” written in 1854, and performed for the rest of his life, Frederick Douglass contends that: “from the various dregs of society, there come men who may well be regarded as the pride and as the watch towers of the [human] race.” Social class does not determine one’s virtue or worth. For the last thirty years of his life, between the legal demise of chattel slavery in 1865 and his death in 1895, Douglass gave hundreds, if not thousands, of speeches, published countless articles, and two books, offering an alternate vision for how humans could conceive of difference between one another. In an 1865 speech, Douglass asserts that good “poets, prophets and reformers,” must act as “picture-makers,” painting for their audiences visions of the future of the human race. They must keep, “ever present” in their “mind some high, comprehensive, soul-enlarging and soul-illuminating idea, earnestly held and warmly cherished, looking to the elevation and advancement of the whole [human] race.” Douglass’s vision, in the last thirty years of his life, is of a world built on virtue.

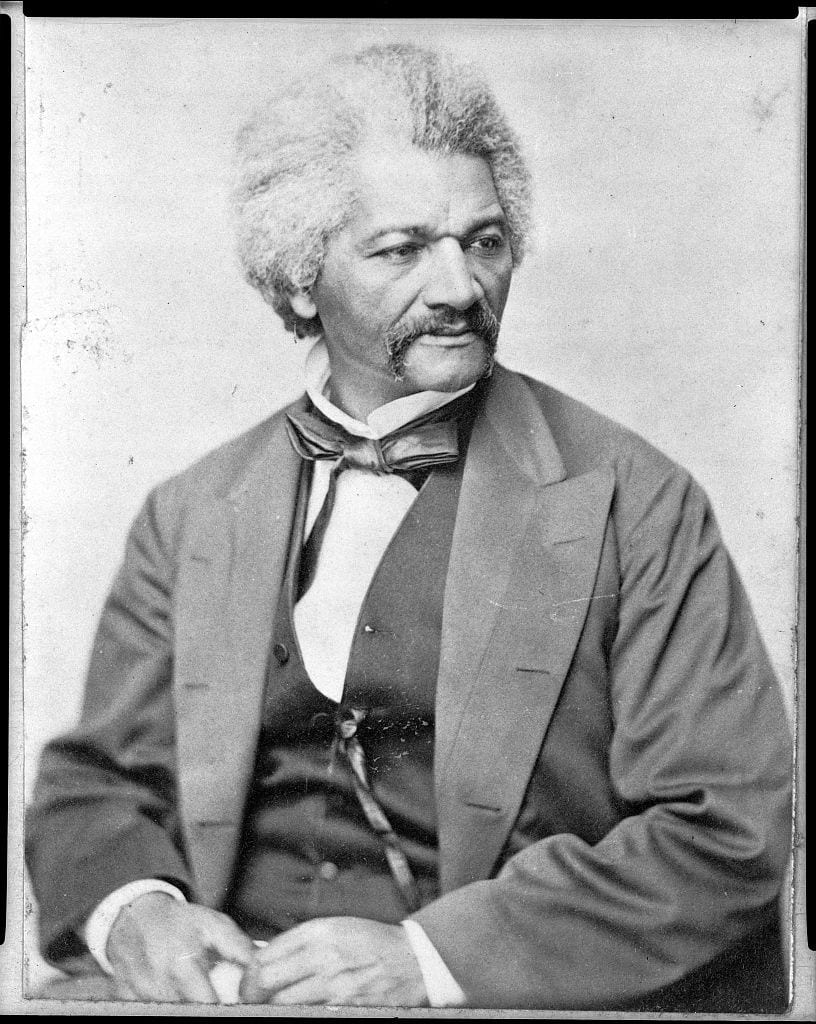

Photographic portrait of Frederick Douglass by George Francis Schreiber, 1870. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Frederick Douglass fought for an America beyond slavery. He believed that emancipation had not merely “emancipated the Negro, but liberated the whites” as well. In an Emancipation Day Address, titled “Emancipation Liberated the Master as Well as the Slave,” Douglass held that the institution of slavery enacted violence against all of its member. In another speech, “Strong to Suffer, yet Strong to Fight,” Douglass declared that since emancipation, people are no longer “required to defend with their lips what they must have condemned in their hearts.” Slavery was a system that forced people to deny the fundamental, to Douglass, truth, that all humans are created equal. By enslaving another person, slaveholders had to violently strip them of a central tenant of their humanity, and had to support their dehumanization with systematic, normalized violence. Slaveholders had to present a united front. They could not speak out against, or even question, the violence and domination that was central to the system.

However, the American promise of Emancipation dissipated. Lynch law dominated the whole nation, as it begun amassing overseas territories. In an 1895 speech, “The Color Line,” he declared that in this supposedly emancipated and advanced society, the “rich man would have the poor man, the white would have the black, the Irish would have the negro, and the negro must have a dog, if he can get nothing higher in the scale of intelligence to dominate.” Though slavery had ended, the mindset that underlay it had survived. People still placed themselves in relation to each other based on characteristics about which they had no power.

Throughout the last thirty years of his life, Douglass fought against all outgrowths of a philosophy built upon prejudice and discrimination. He fought against sharecropping. He supported the work of women’s rights, calling himself a “radical women’s suffrage man” and declaring that granting women the power to vote would be “the greatest revolution” that the world had ever seen. Douglass lent his voice to the struggle for reparations for the formerly enslaved, arguing across a number of speeches and in a widely circulated pamphlet that “American slaves were emancipated under extremely unfavorable conditions. (…) even despotic Russia gave a plot of land and farming implements to its emancipated serfs and (…) when the Jews left Egypt they were allowed to take their former masters’ jewelry.” On this basis, he called for reparations for the formerly enslaved in America. Douglass rhetorically supported the rights of Christians in the Ottoman Empire, Jewish people in Europe, and stood behind oppressed Chinese laborers in California. The philosopher even supported the rights of animals to be treated well, admonishing farmers not to beat their work animals.

In the vision of the world that Douglass offered his listeners, the highest ideal of a person was one who was like God. In a speech of the same name, Douglass argues that “Good men are god in the flesh.” Across a number of eulogies and public speeches, he extolls as examples of this his fellow abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, and Lucy Stone. In Douglass’s phrasing, Garrison becomes “the man–the Moses, raised up by God, to deliver his modern Israel from bondage.” Abraham Lincoln, he declares in a speech on “Great Men,” likewise, possesses “a more godlike nature than” any man he had ever met. Though he often uses wealthy and famous men as his examples, Douglass acknowledges “wealth and fame are beyond the reach of the majority of men.” Still, “personal, family and neighborhood well-being stand near to us all and are full of lofty inspirations.” If everyone worked towards the betterment of themselves and their communities, Douglass contends, “we should have no need of a millennium. The world would teem with abundance, and the temptation to evil in a thousand directions, would disappear.” Everyone could become godlike.

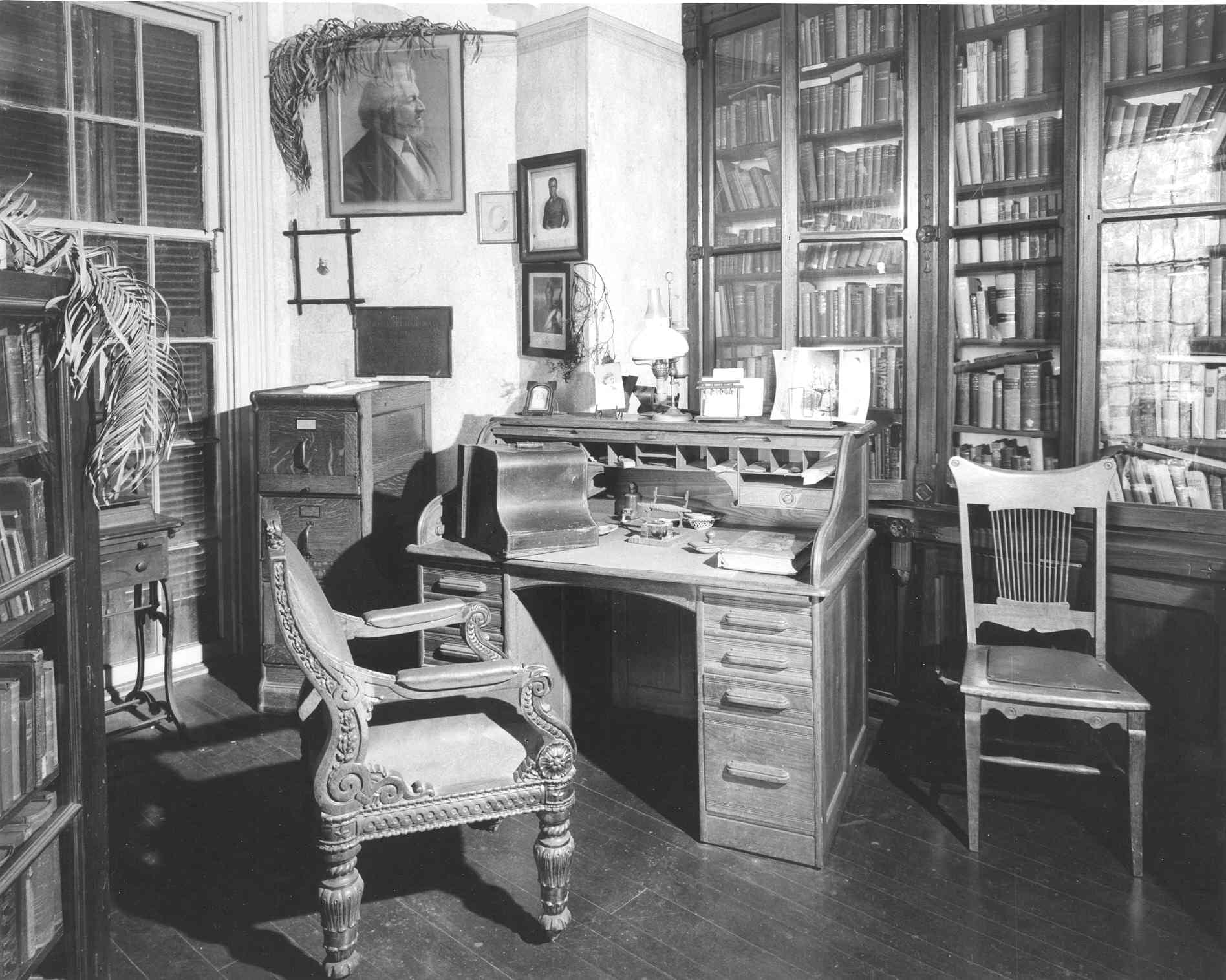

Frederick Douglass’ study and library in 1962. Note portraits of Toussaint L’Ouverture, himself. Out of frame are pictures of his other heroes: Abraham Lincoln, William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Philips, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and others. Image courtesy of the National Park Service.

Frederick Douglass’s philosophy of virtue was not wholly new. It fit into a tradition of radical humanist and liberal thought going at least far back as the reformation. In a 16th century poem, the Settennario, God appears to the author, only known as Scolio, and explains that he had given to each group of people on earth “Ten Commandments to each of them The same, but which they comment on separately.” He goes on to explain that each group of people could go to heaven if they just followed their own set of commandments, which were quintessentially the same.

Douglass took many ideas from the famous Scottish historian and enlightenment thinker, Thomas Carlyle’s On Heroes and Hero Worship (1840). In the work, Carlyle argues that “the history of what man has accomplished in this world, is at bottom the History of the Great Men.” Each chapter is dedicated to a different form of innate greatness and a different person who exemplified such greatness in their society’s history. All but one of Carlyle’s great men are white and European. The only exception is the prophet Muhammad, whom Carlyle describes as “by no means the truest of Prophets; but I do esteem him a true one.” While Carlyle evinces a theory of virtue as based on thought and action, he ends up supporting a tautology. Someone is great because they greatly impacted the world. Carlyle’s philosophy, then, implies that people who do not greatly impact the world must be morally inferior. Consequently, Carlyle held that the “African race” was incapable of producing Great Men. In 1849, nine years after publishing Heroes, Carlyle anonymously published an article titled “Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question,” in which argued that African people were naturally inferior to whites and because of their inherent degradation, fit to be slaves. In the face of derision and public humiliation, Carlyle stuck to his beliefs, republishing the piece with an even more overtly racist message as a pamphlet in 1853.

As an abolitionist, woman’s suffrage man and radical, Douglass sought to open up greatness to all people. As a result, he needed to have a clear conception of what godliness did and did not look like. In an outline to a speech, written during his visit to Egypt in 1884, Douglass accuses Egyptian Coptic Christians of being “Mohamedan in custom” and points out disparagingly that “their women are veiled.” Only American missionaries could bring true Christianity and education to the Egyptians. “It is the redeeming of the land” from misrule and misbelief, Douglass wrote, and “the bringing to people our knowledge of the” gift of education “that is its great need.” They have been “establishing schools, distributing Bibles, showing the people how to be clean, how to live virtuously, which is to live healthfully + honestly.” American protestants needed to teach the “degraded” people true virtue. By opening up virtue to some, he had closed it off to others. Carlyle’s definition of virtue could be malleable, allowing even Muhammad to be great, because he had restricted virtue to the achievements of a single class and, essentially, geographic setting.

However, in an era marked by the rise of Lynch Law, across the U.S. American South, restrictions on voter rights, and a turn away from African American rights across the nation, Frederick Douglass travelled widely, and used his podium to argue that any person, notwithstanding physical attributes, class, or caste, could attain virtue. Douglass built his conception of virtue on a long tradition of a not-quite-universal universalism. Douglass was, and remains, far from alone in not being able to accept that other systems of virtue could be equally valid, nor that other gods could be equally divine.

Daniel Joslyn is a PhD student studying History at New York University. He is currently interested in histories of joy and emancipation in the United States, and the Ottoman Empire (though he’s figuring that one out slowly). He completed his B.A. at Hampshire College studying “Frederick Douglass’s Poetry, Prophesy and Reform: 1880-1895.” He holds that good history is good philosophy and good philosophy teaches us how to live.

Further Reading:

- David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass’ Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee (LSU Press, 1991).

- Frederic May Holland, Frederick Douglass The Colored Orator, Revised Edition (New York: FUNK & WAGNALLS COMPANY LONDON AND TORONTO, 1895).

- John Stauffer, The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race (Harvard University Press, 2009).

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, Representative Men. (based directly on Carlyle’s work, which Douglass also devoured).

- Alexander Pope, Essay on Man (an enlightenment poem that Douglass often quotes on virtue)

November 4, 2016 at 12:57 pm

As a writer that first paragraph pretty much sums it all up for me. Great motivation and reminder to keep that picture of the world we want to paint “ever present.”

February 8, 2017 at 5:31 pm

You article reminded me of a passage from the Oxford Qur’an (5.48) where it states that God made men of so many different nations and religions so that they all might compete with each other in being good, or as you might put it, virtuous.