by guest contributor Charles Cuykendall Carter

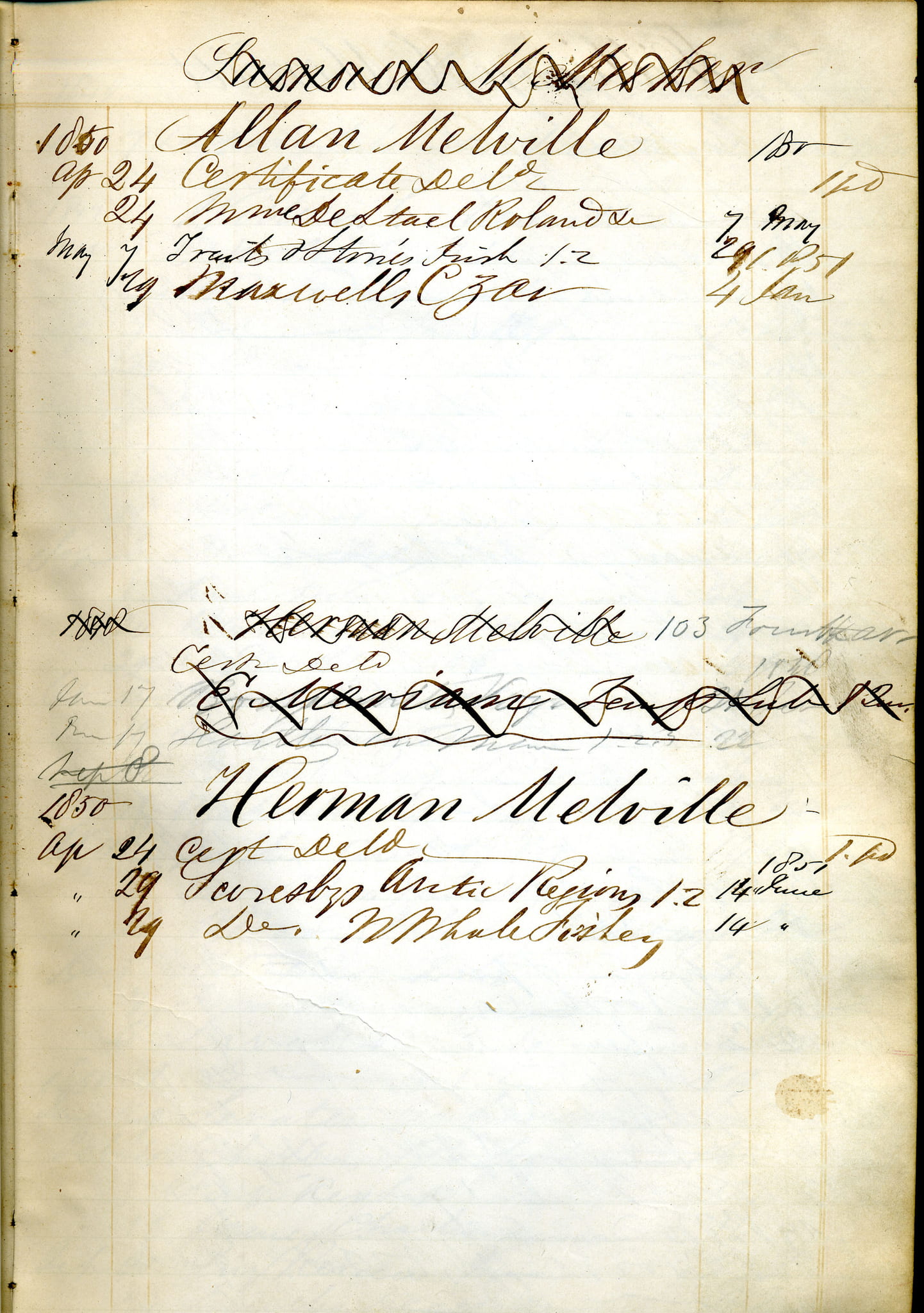

Circulation ledger featuring Melville’s Society Library borrowing history, 1847-50. New York Society Library.

The New York Society Library’s current pop-up exhibit explores the life and experiences of Herman Melville in New York City, during the time leading up to the 1851 publication of Moby-Dick. The more specific, and more intimate, concern of the exhibit is the symbiotic relationship between an author and his library, both as a site of research and as a vehicle for promotion.

For much of 1848, and then again for a time in 1850, the Society Library was Melville’s library. (He did also personally own a good number of books, many of which he annotated; some can be seen in digitized form through the impressive Melville’s Marginalia website.) While in the throes of composing his masterpiece, Melville regularly spent time doing research in the reading room of the Society Library, then on Broadway and Leonard Street. He was again a Society Library member in the years before his death in 1891.

Some treasures from the Society Library’s archives featured in the exhibit vividly demonstrate Melville’s membership and activity. One charming display item is a facsimile of Melville’s 1850 Society Library membership certificate, reproduced on cardboard and able to be handled and examined up close. Other indices of Melville’s personal relationship to the Library include a contemporary city directory listing Melville’s home address at “103 Av. 4,” about a half-hour’s walk away; and his large autograph signature in a circulation ledger, dated 1850.

Most exhibition materials reflect Melville as author. Among them are the first published excerpt of Moby-Dick in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine of fall 1851, and a facsimile of an early manuscript invoice showing Society Library purchases of Melville books.

The largest exhibit piece is a pin-board chart covered with index cards, which are connected with tightly-strung lengths of different colored yarn. The cards represent specific Society Library readers; the yarn, Melville’s first seven novels. The display renders visible for the viewer what is addressed by most modern introductions to Moby-Dick: upon publication, it was a commercial dud.

Melville’s earlier, less complex, more straightforward travel adventures—Typee, Omoo, White-Jacket—were in frequent circulation at the Society Library in the late 1840s–early 1850s. Moby-Dick was borrowed fewer than twenty times during the period represented by the chart. Melville’s next book, Pierre, was even less popular—and, as the exhibit points out, earned him the headline “Herman Melville Crazy” from a contemporary reviewer.

Perhaps the most amusing exhibit item shows a unique exchange between Society Library readers of Melville. In what amounts to a nineteenth-century version of internet comments (including insults and a silly pseudonym), at least three Library members left penciled notes at the end of a chapter of White-Jacket:

[annotator 1:] This is a bad chapter. / E. B. / July 5 1860

[annotator 2:] Why the devil don’t you put the real date in. (Signed) Adolphus Fitz Noodle

[annotator 3:] I should think you were a noodle indeed. G.J.V.

Also on display are several mid-nineteenth-century scenes—prints and photographs of the New York City harbor—artfully paired with quotations from Moby-Dick. A panoramic engraved view of the city from the East River accompanies Ishmael’s opening admission that seafaring adventures are his cure for frustrations with obnoxious city life, when “it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off . . . .”

The absent star of the exhibit, the barely-circulated first edition of Moby-Dick belonging to the Society Library, is unfortunately now lost, perhaps disappeared in its depths.

“Herman Melville’s New York, 1850” is on display, free to the public, at the New York Society Library, in the Peluso Family Gallery, until November 7.

Charles Cuykendall Carter is the Assistant Curator of the Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle at the New York Public Library. He is also Associate Editor of the Shelley-Godwin Archive, and is on the board of The American Printing History Association.

Leave a Reply