by guest contributor Michael Savage

In the United States, segregated metropolitan areas are a national phenomenon, with heavily minority inner-cities typically ringed by much wealthier and predominantly white autonomous suburbs. According to 24/7 Wall St., America’s three most segregated cities are in the North. Cleveland possesses the dubious honor of being America’s most segregated metropolis, followed by Detroit and Milwaukee. Boston takes seventh place, just edging out Birmingham, Alabama, a city whose terroristic violence against African Americans once earned it the nickname “Bombingham.”

This segregation did not occur as the result of impersonal market forces. Significant discrimination – both public and private – produced today’s segregated metropolises. Federal policies instituted during the New Deal had the effect of guaranteeing mortgages for whites only, while the refusal of many whites to sell to African Americans and the considerable community violence that often greeted black “pioneers” who moved to all-white neighborhoods helped solidify metropolitan racial divisions. Historians have told these stories and told them well. This history, however, is incomplete.

For a deeper understanding of metropolitan segregation, historians need to examine the alternate visions of metropolitan desegregation articulated by a most surprising source – segregationist urban whites. In battles over urban school segregation in the American North, it was urban whites of clear segregationist leanings who most forcefully pushed for desegregated metropolitan areas, demanding that desegregation reach beyond the political boundaries of the central city. While this may seem counterintuitive, it was simple pragmatism. Segregationist urban whites proposed metropolitan desegregation to weaken suburban support for integration but also because successful metropolitan desegregation meant a dispersal of the black student population throughout the region, ensuring the maintenance of white majority schools. These metropolitan proposals had the potential of combatting metropolitan inequality. Their failure, in the years following the push for civil rights in the American South, helps explain the near total separation of city and suburb and why Northern metropolises top the list of the most segregated regions.

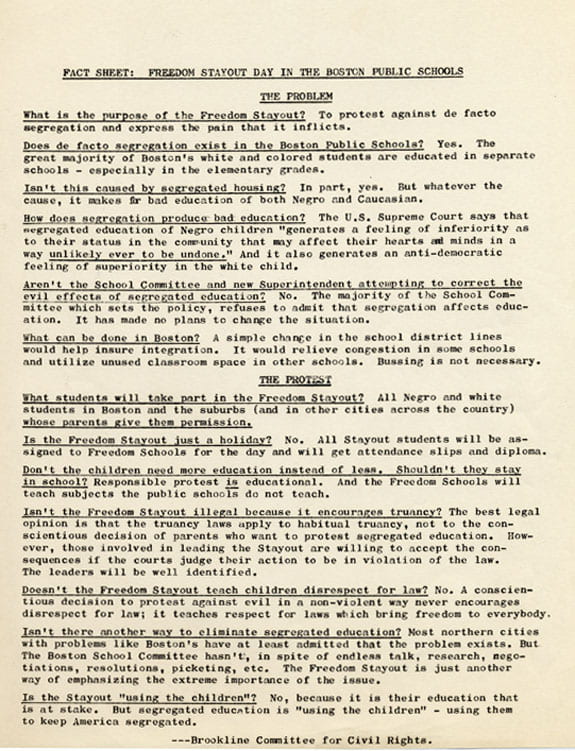

A fact sheet on the Freedom Stayout prepared by the suburban Brookline Committee for Civil Rights. Courtesy Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

Boston, most known for its vehement opposition to desegregation busing, witnessed the longest and most widespread consideration of metropolitan school desegregation. When faced with 1965 Racial Imbalance Act that declared any school with over 50 percent “nonwhite” students “racially imbalanced,” the Boston School Committee responded with a strategy designed to weaken suburban legislative support for integration by proposing that the suburbs participate in mandatory desegregation. This strategy is evident in School Committeeman Joseph Lee’s satirically titled “A Plan to End the Monopoly of Un-light-colored Pupils in Many Boston Schools.” Lee’s first suggestion was to “notify at least 11,958 Chinese and Negro Pupils not to come back to Boston schools this autumn.” These students, a majority of Boston’s minority student population, were to attend suburban schools in order to integrate the suburbs. The suburbs, home to three times Boston’s population, averaged less than one percent black students in their public school populations, which Lee called “racial imbalance, if ever there was.” Though clearly designed to undermine the law and certainly not indicative of any moral commitment to civil rights, Lee’s satirical plan nevertheless raised valid questions about segregation in the metropolitan context.

Lee’s plan bore similarities to the voluntary Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO), which voluntarily bused black students from Boston schools to several suburban communities with available school seats. Jointly created by liberal suburbanites and Boston civil rights advocates in 1966, METCO offered city students access to superior suburban schools, provided a measure of socioeconomic integration, and made a contribution to lessening school segregation in the region. However, like the Racial Imbalance Act, METCO functioned at the farthest limits of suburban liberalism. It did not require that suburbanites send their children to black city schools, did not couple black school attendance with increased black residence in the suburbs, and its suburban founders, fearful of a loss of suburban support, downplayed their aims of full metropolitan desegregation.

The Boston School Committee faced several legal challenges to its segregation, none more important than the Morgan v. Hennigan case initiated by the Boston Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in March 1972. In its filing, the NAACP urged the “inclusion of suburban school systems as appropriate in the plan for desegregation, in order to achieve, now and hereafter, the greatest possible degree of actual desegregation.” In May the Boston School Committee voted four-to-one to ask the court to include 75 suburban communities as its co-defendants, seeking a metropolitan desegregation plan in the almost certain outcome of being found guilty.

As similar events in Detroit demonstrated, the Boston’s School Committee’s courtroom calls for metropolitan desegregation had the very real possibility of implementation. When the Detroit Board of Education approved a modest integration plan in April 1970, anti-integrationist whites formed the Citizens’ Committee for Better Education (CCBE) and successfully recalled integrationist Board members. The rescission of the integration plan prompted a legal challenge from the NAACP. Faced with the likelihood that the Detroit schools would be found unconstitutionally segregated, the CCBE urged the adoption of a plan of metropolitan desegregation just one year after recalling integrationist Board members. It was the first party in the case call for a metropolitan solution, and was quickly joined by the NAACP. CCBE members supported plans of metropolitan desegregation for the same reason they opposed intra-city desegregation – both emanated from a desire to keep their white children in white majority schools. CCBE Attorney Alexander J. Ritchie persuaded CCBE members to change course, telling them that “Your kids are going to go to school, and they’re going to be bused, whether you like it or not… Now do you want your kids to go to school where they’re the minority in a basically black school system, or do you want them to go to school where you’re still the majority?” Divergent motivations produced similar results. So similar were metropolitan plans produced by the CCBE and the NAACP that Judge Stephen J. Roth called them “roughly approximate.”

While Judge Roth accepted the CCBE’s metropolitan arguments and ordered the implementation of a desegregation plan affecting 54 independent school districts, the Supreme Court did not. In a strictly partisan five-to-four decision, in July 1974 Justice Potter Stewart joined Republican President Richard Nixon’s four appointees in reaffirming the separation of city and suburb, ensuring the maintenance of separate and unequal education in American metropolitan areas. As Justice Thurgood Marshall noted in his impassioned dissent, the Court’s decision would allow “our great metropolitan areas to be divided up each into two cities – one white, the other black.” Though this divide already existed, the Milliken decision exacerbated metropolitan segregation and helped codify metropolitan inequality.

As historian Matthew Lassiter’s analysis of desegregation in Richmond, Charlotte, and Atlanta demonstrates, school desegregation plans that incorporated the suburbs provided more lasting integration than plans limited to the central city alone. Affecting the entire region, metropolitan plans did not allow well-heeled whites to simply flee the desegregation mandate by leaving the city. In light of both cities’ re-segregated schools that are attended almost uniformly by the intersecting categories of poor and minority and their persistent residential segregation, it is worth revisiting these proposals. Undeniably conceived in white racism and prone to viewing black students as a problem population that needed to be dispersed, in such metropolitan plans also existed possibilities of meaningful racial and socio-economic integration.

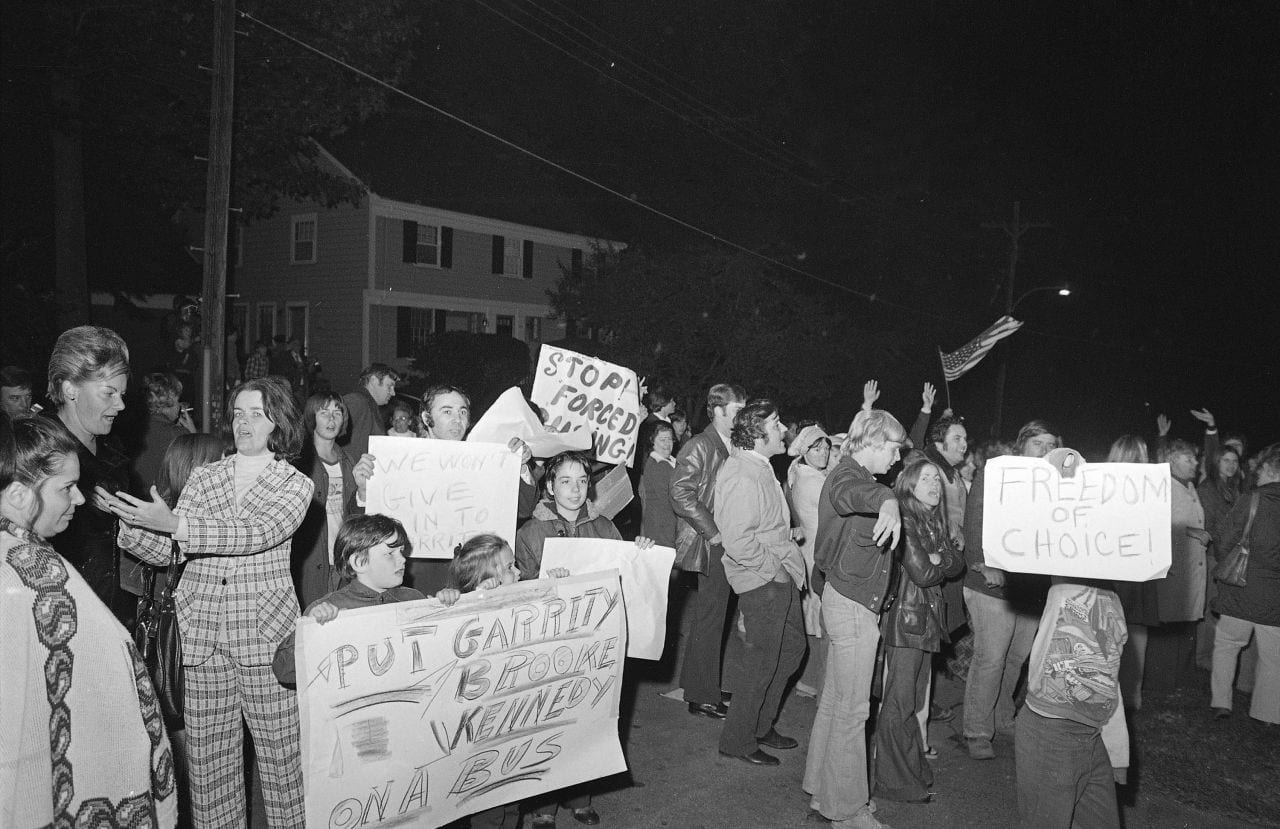

White Boston parents demonstrating outside Judge Arthur Garrity’s suburban Wellesley home. Though their protests primarily targeted arriving black students and buses, anti-busers frequently trekked to the suburbs to protest busing and decry elite busing supporters whose suburban residences placed them outside the desegregation mandate. Image courtesy WBUR FM.

The metropolitan proposals made in Boston and Detroit have been most influential in their failure. With mandatory metropolitan desegregation an impossibility, middle-class whites accelerated their flight from the central cities and the public schools. Suburbanites worked to ensure suburban autonomy from the central city. In Boston, a program proposed by 56 school districts before the busing decision that was designed to entirely eradicate segregation in the metropolitan area was hardest hit by the renewed push for suburban autonomy. In the program’s first and only year, 1976-77, a mere 210 students from three suburbs and Boston participated in its school pairing program. Suburbanites opposed participation in the program, fearing that it would lead to a metropolitan school district and mandatory busing. While the METCO program continued, it never experienced another period of growth and previously stalwart communities threatened to withdraw when the state planned to modestly trim the funds it provided to participating communities.

While historians have noted an increase in white flight following intra-city desegregation, they have failed to connect this to declining support for metropolitan cooperation and governance in the 1970s. Conversely, the burgeoning literature on “metropolitics” neglects the long history of proposals for metropolitan school desegregation. This is a mistake. A focus on proposals for metropolitan desegregation made by ostensibly segregationist urban whites allows for a broadened understanding of the history of metropolitan reform, urban history, and civil rights. This focus helps explain the growth and persistence of extreme disparities between the central city and its suburbs in America’s metropolises, particularly those in the North, and can help account for the lack of metropolitan solutions to a wide array of metropolitan problems.

Michael Savage is a graduate student in American History at the University of Toronto whose dissertation focuses on metropolitan approaches to school and housing desegregation.

Leave a Reply