by guest contributor Rob Koehler

Daniel Tompkin’s collegiate essay. Image courtesy of the HathiTrust Digital Library.

Like a lot of college students today, Daniel Tompkins (1774-1825) spent much of his four years at the newly named Columbia College [now University] writing essays. Foreshadowing his later political commitments as New York Governor from 1807-1817, he wrote about topical issues, pressing problems of social justice, and more abstract problems like the persistence of prejudice. Tompkins proved to be quite liberal in most of his sentiments, as in his arguments for the abolition of slavery, the end of capital punishment, and the demotion of the classical curriculum in the collegiate course. Yet, for the purposes of this essay, Tompkins most interesting piece is “On Novels,” in which he defends fiction reading as a valuable part of an education. Tompkins begins his essay by noting he was taught that novels were “solely for the amusement of puerile minds” but eventually came to realize that simply accepting this opinion was like being a child who “by [his] catechism [was] taught to admit principles as true without being convinced of the truth of them as [he] ought to be by [his] own reason”. And Tompkins’ reason taught him to enjoy novels; in fact, he was willing to go so far as to relate the reading of novels to that of his own formal education at Columbia, writing:

It is further remarked, that novels have a bad tendency, by possessing a power of alluring the reader and cause him to devote his whole attention to them. Mathematicks it is observed have the same tendency to those who have a relish for the pleasure arising from that study, yet in my humble opinion, this is not a sufficient demonstration to shew, that Mathematicks ought to be avoided.

Writing after having completed the mandatory two years of Mathematics required of Columbia students, Tompkins had the academic experience to make the comparison. It seems unlikely that most young men—who would have studied arithmetic as an effort to better their employment prospects during apprenticeship or after the work day had ended—would have shared Tompkins’ perspective on the subject and its more than practical purposes. It was his privileged position as a college student that made the comparison both sensible and useful.

In the early United States and in the Anglophone world more generally, criticism and praise of novels centered around their moral qualities and their impact on young women, not on young men. In her magisterial study of early American novels and novel readers, Cathy Davidson focuses almost exclusively on the uses of novels as an informal—and somewhat subversive—education for young women in the dangers and possibilities of heterosociability, courtship, sexual relationships, and marriage. A wealth of letters, diaries, and other sources back up Davidson’s claim, showing how female characters and the narrative frameworks of novels were taken up by young women to discuss their misgivings, fears, and hopes about their futures. Yet, how did novel reading impact the intellectual lives of young men?

After all, no early American cultural pundit decried the deleterious impact of novel reading on young men or espoused his or her fear that it would lead to their seduction, ruin, and premature death. This gap emphasizes the sexist and overtly regulatory functions of this kind of criticism of the novel, but it does not answer the question of whether young men read novels as avidly as young women, or what exactly that activity meant to them. Some scholars—such as Bryan Waterman and Robb Haberman—have noted that, like young women, young men also used the literary language of the novel when engaging in romantic and sometimes sexually charged relationships and thus it became one mode of conducting a romance in the early Republic.

Based on Tompkins’ essay though, I suggest that the novel was also a part of the informal education of young men that became for many a lifelong interest. The records of the New York Society Library from 1789-1792 document the reading of nineteen unmarried young men—all of them, like Tompkins, students or recent graduates of Columbia—who all checked out and read novels in addition to the history books, Latin translations, and reference books that they were likely using to accompany or supplement their courses. This cohort of young men such as John L. Norton, Samuel Jones, and James Parker showed many of the behaviors decried by critics of young women’s novel reading. They regularly selected the newest rather than the best, they read salacious scandal fiction like Retribution or The Convent, and they read very quickly, often returning a volume of a novel the day after they checked it out. But, they did all of this while also taking out a steady stream of works like Robertson’s History of America and Adam Ferguson’s History of the Roman Republic. These habits show that, just like teenagers today, college students in the early Republic were multi-tasking, moving fluidly between various tasks and types of reading.

This is not to say that reading novels was not important but to say that it took place in a larger context of engagement with the printed word; for these privileged young men of the early Republic, novel reading was, as much as Mathematics, a part of a liberal education. What is perhaps most interesting is that for readers in this cohort, novel reading remained a pursuit after the end of their educational careers in a way that the reading of other types of works, many of which had been required for their educations, did not. Because the library’s records between 1792-1797 are lost, there is a particularly jarring difference in borrowing for many of these men between their college days and their adult reading. In their adult years, novels predominate in almost every reader’s record. While this might be evidence that a wife or child is using the account, the preponderance in so many accounts suggests that it is the men themselves.

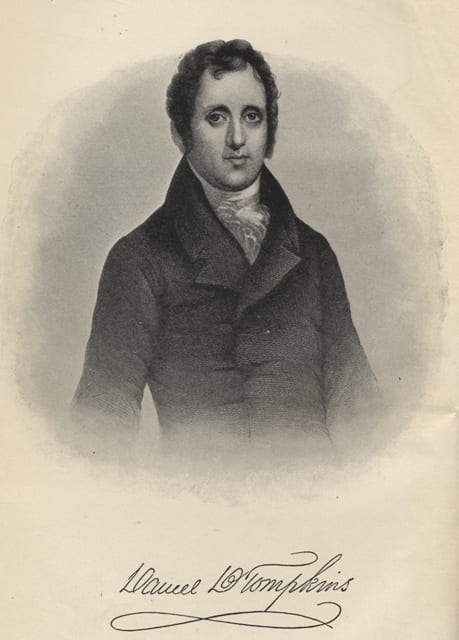

Governor and Vice President Daniel D. Tompkins. Image courtesy of the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library.

And this returns me to Daniel Tompkins and a peculiarity in his comparison of reading novels to studying Mathematics. Tompkins ends by commenting that “Mathematicks. . . have the same tendency to those who have a relish for the pleasure arising from that study, yet in my humble opinion, this is not a sufficient demonstration to shew, that Mathematicks ought to be avoided.” Tompkins is as much complaining about the dullness of Mathematics for most students as he is highlighting the enjoyability of reading a novel. As the reading habits of others his age and background suggests, higher education did not generally invoke a passion in early American students to pursue learning for the love of it, instead they embraced novel reading as both educative and pleasurable. More generally, I think Tompkins’ defense of novel reading makes clear that whatever their more intimate and immediate purposes for young people during this period, novel reading often became—and still becomes for many young people—a steady habit, one that continued after reading required for other purposes fell away. None of these men—unlike Tompkins himself who later became a Governor and then Vice President—would become particularly famous or well known in a field of endeavor in the early Republic, and most would lead lives that left little trace. They all, however, seem to have made separate yet unquestionably linked decisions to embrace the reading of novels over other forms of improving intellectual pursuits that had formed a part of their formative education.

In an earlier post for this blog, I suggested that as scholars we have yet to consider what it would mean to develop a history of reading for pleasure instead of for purpose, or to develop a history of reading that did not place these two objectives in tension but, as these Columbia students did, instead in purposive relation. Reading for pleasure is not an act of non-purposiveness but an act of a different purpose altogether. The life of the mind does not solely originate in planned study and courses of reading, in the aggressively organized, disciplinary spaces of universities and learned sociability; it also develops in the intimate and complex relationships between individuals, texts, and lived experience that persist as much because of their often inexplicable enjoyability as their expressed purpose or lack thereof.

Rob Koehler is a PhD. candidate in English at New York University. He works at the intersections of education, literature, and publishing in early America, examining the political, legal, and cultural origins of schools and libraries as public institutions.

1 Pingback