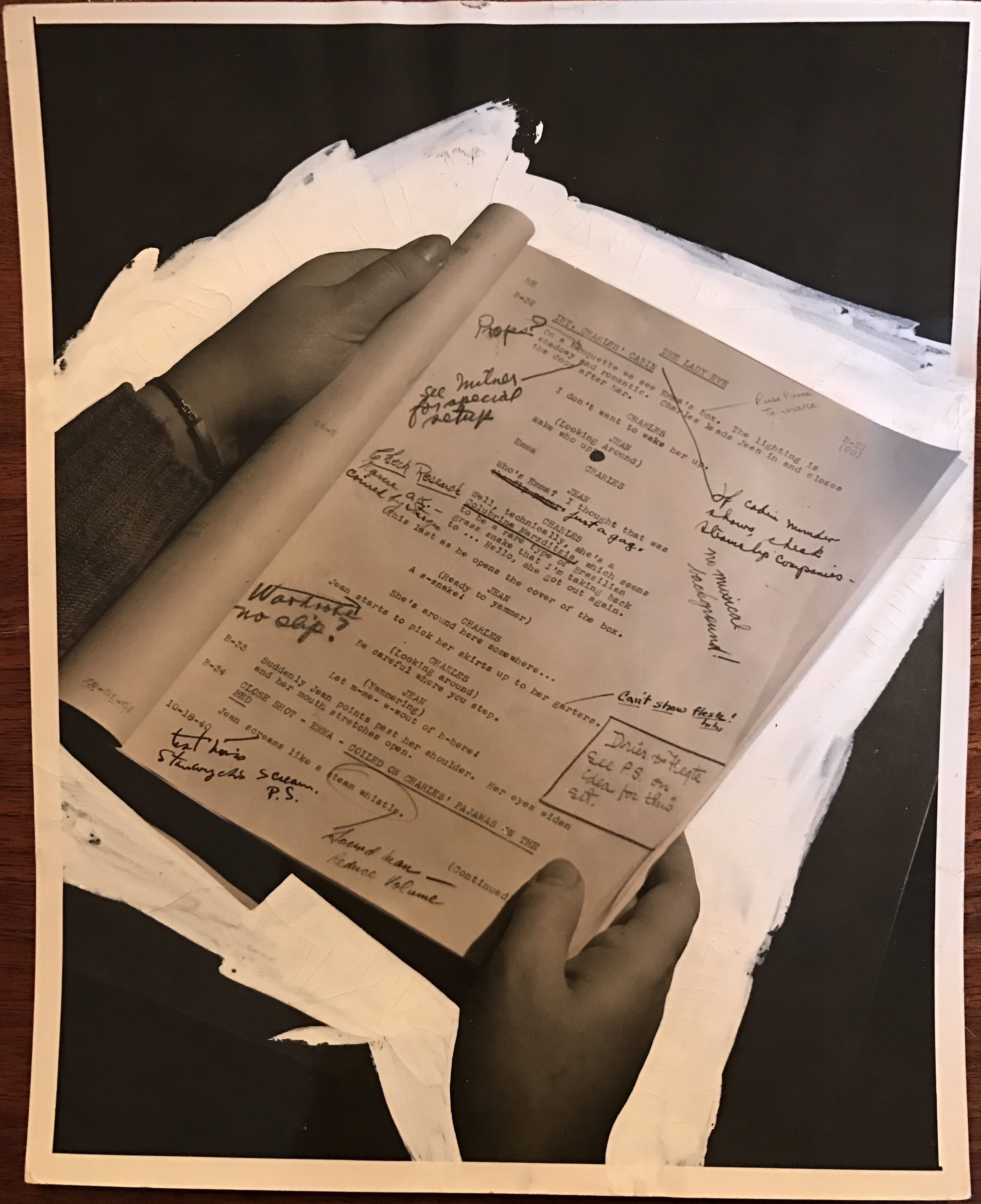

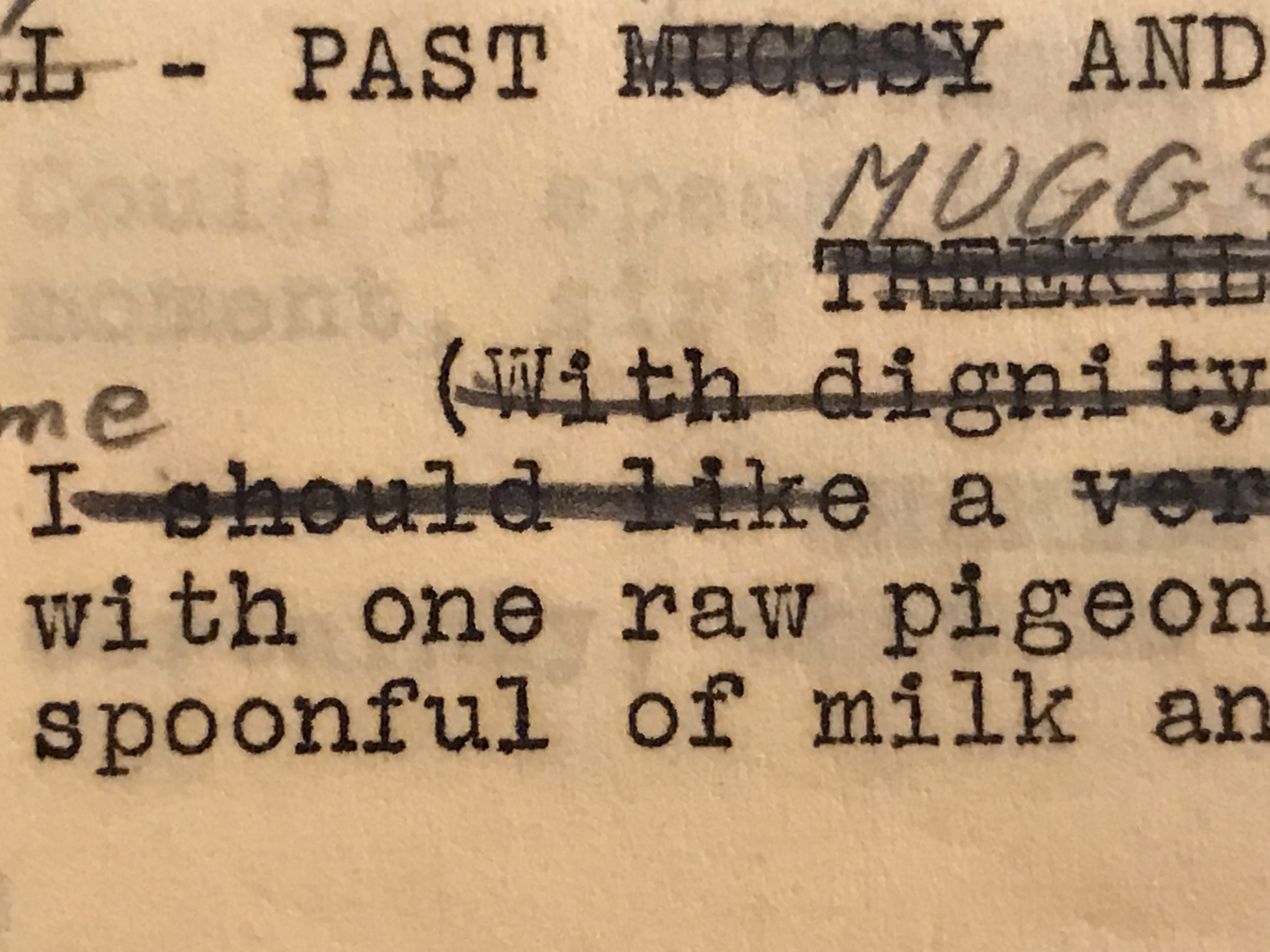

Press photograph of disembodied hands holding a heavily annotated script for The Lady Eve (Paramount, 1941) by Hal McAlpin. From the Collection of Robert M. Rubin.

Like a literary manuscript in a publisher’s office, screenplays face rounds of revision and annotation in the motion picture studio. In the photograph above, someone holds a draft script for The Lady Eve, marked up with notes in several hands. Screenwriter and director Preston Sturges initialed a note in ink to “test… [lead actress Barbara] Stanwyck’s scream,” which a typed stage direction notes should sound like a steam whistle. Penciled notes in at least two other hands highlight facts to be checked, details about props and costumes, and mark stage directions that risk violating the Hays Code. This photograph – taken by still photographer Hal McAlpin and marked up for print publication – highlights the role of print in the transformation of a fictional narrative to a motion picture.

The disembodied hands are almost certainly script supervisor Claire Behnke’s (1899-1985), and their presence symbolize the relationship not only between the film script and the script supervisor, but the whole of the Paramount Stenographic Department. During the pre-production and shooting phases of motion picture making, script supervisors, clerks, and typists – typically women but sometimes male secretaries to screenwriters and directors – coordinated the changes made daily to the ur-text of the Hollywood picture. As drafts circulated among the specialized departments within a studio, script clerks and typists in the Stenographic Department collated these changes and produced new drafts in multiple copies as the entire team worked toward the completion of a final master-scene shooting script.

Book historians and bibliographers know well the analogous journey from manuscript to print. In the early modern period, bookmen like Aldus Manutius collaborated with editors, type designers, and compositors with specialized skills to transform the manuscript texts of authors living and dead into stable and faithful printed texts in multiple copies for wide distribution. This often required substantive correction of the original manuscript and proofs of the printed text, often to a living author’s great surprise and dismay. The role of editors, illustrators, and type designers have evolved since the introduction of industrialized printing technologies in the mid-nineteenth century, but the importance of their relationship to the writers they work with and more generally to the production of printed works of scholarship, fiction, and poetry, has not diminished. And as Leah Price and Pamela Thurschwell have pointed out in a co-edited collection of essays, Literary Secretaries/Secretarial Culture, typists have played an important role in the creation and consumption of literary (and non-literary) texts, too.

Like literary manuscripts, draft film scripts are complex artifacts of the process of correction and collation, but the end product is arguably much more complex. The motion picture relied not only on actors and directors, but specialist technicians who worked with sets, props, cameras, lighting, and sound equipment to craft a coherent, continuous narrative. Histories of film and screenwriting have thus focused on the way the text and format of the script evolved to coordinate this effort. Scholars Janet Staiger, Marc Norman, Tom Stempel, and Steven Price have described the evolution of the screenplay from the silent to the sound era, with a special focus on the development of the scenario, continuity, and master-scene scripts and the kinds of information contained therein. But in doing so, they’ve neglected the roles of the stenographic departments and the technological specialists employed by film studios and their relationships to the scripts they produced.

Three drafts of The Lady Eve survive today in independent curator Robert M. Rubin’s collection of scripts and other artifacts of the film production. Two date from October of 1940; the third, and earliest, contains a combination of material from an early draft dated December 1 and 2, 1938 with later revisions dated September 23, 30, and October 4, 1940. Revisions for Sequences A and B of the film accompany this script in a separate stapled packet dated August 26, 1940. Citing materials in the Preston Sturges Papers at UCLA and the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Library, Turner Classic Movies notes that Sturges was forced to draft- and re-draft the play between 1939 and 1940 after criticisms from producer Albert Lewin, and after the Motion Picture Academy determined that “‘the definite suggestion of a sex affair between your two leads’ which lacked ‘compensating moral values.’” While the 1938-1940 draft in the Rubin collection is not the earliest surviving screenplay for the film (UCLA holds two earlier drafts), it’s an important record of the evolution of the text.

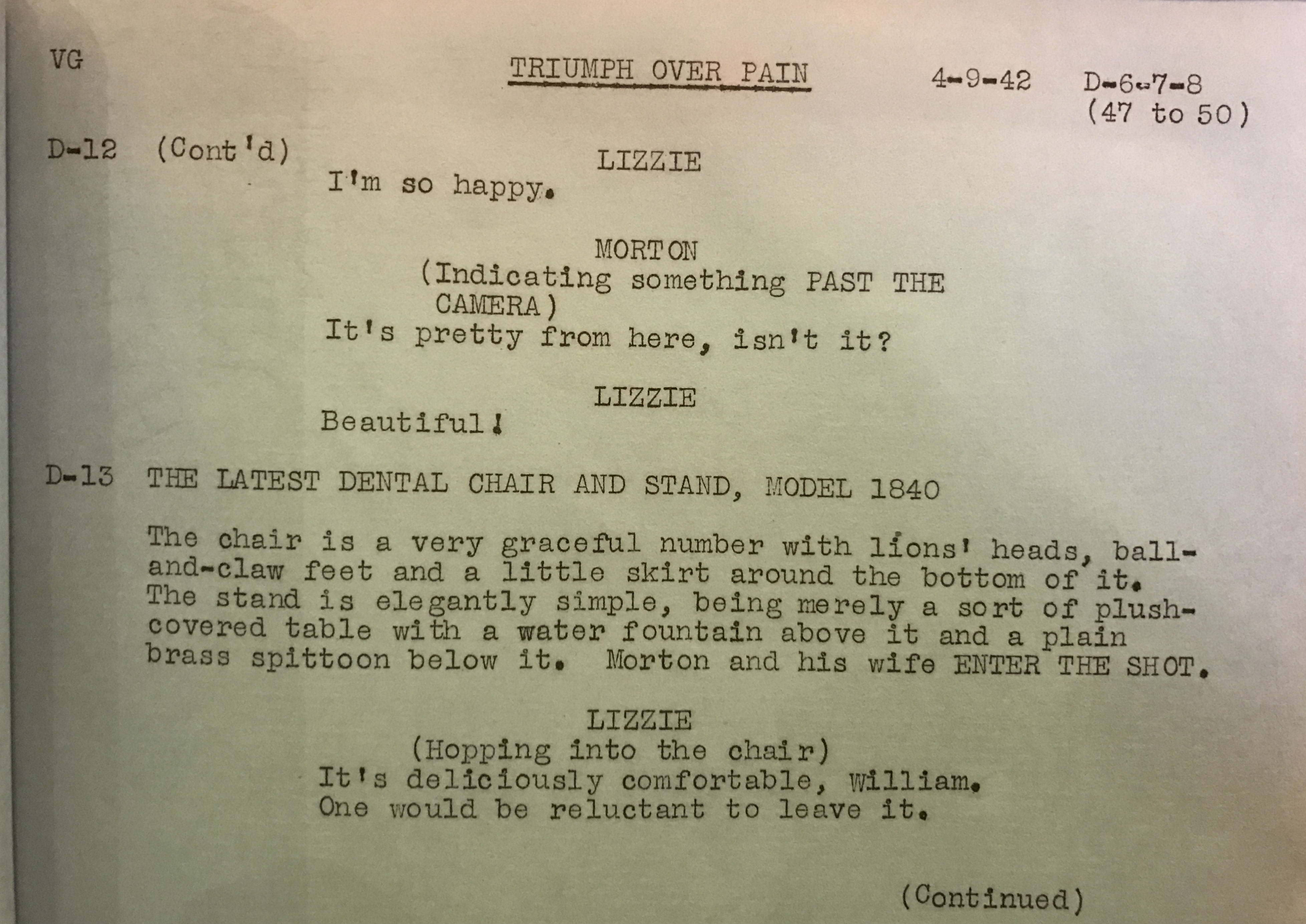

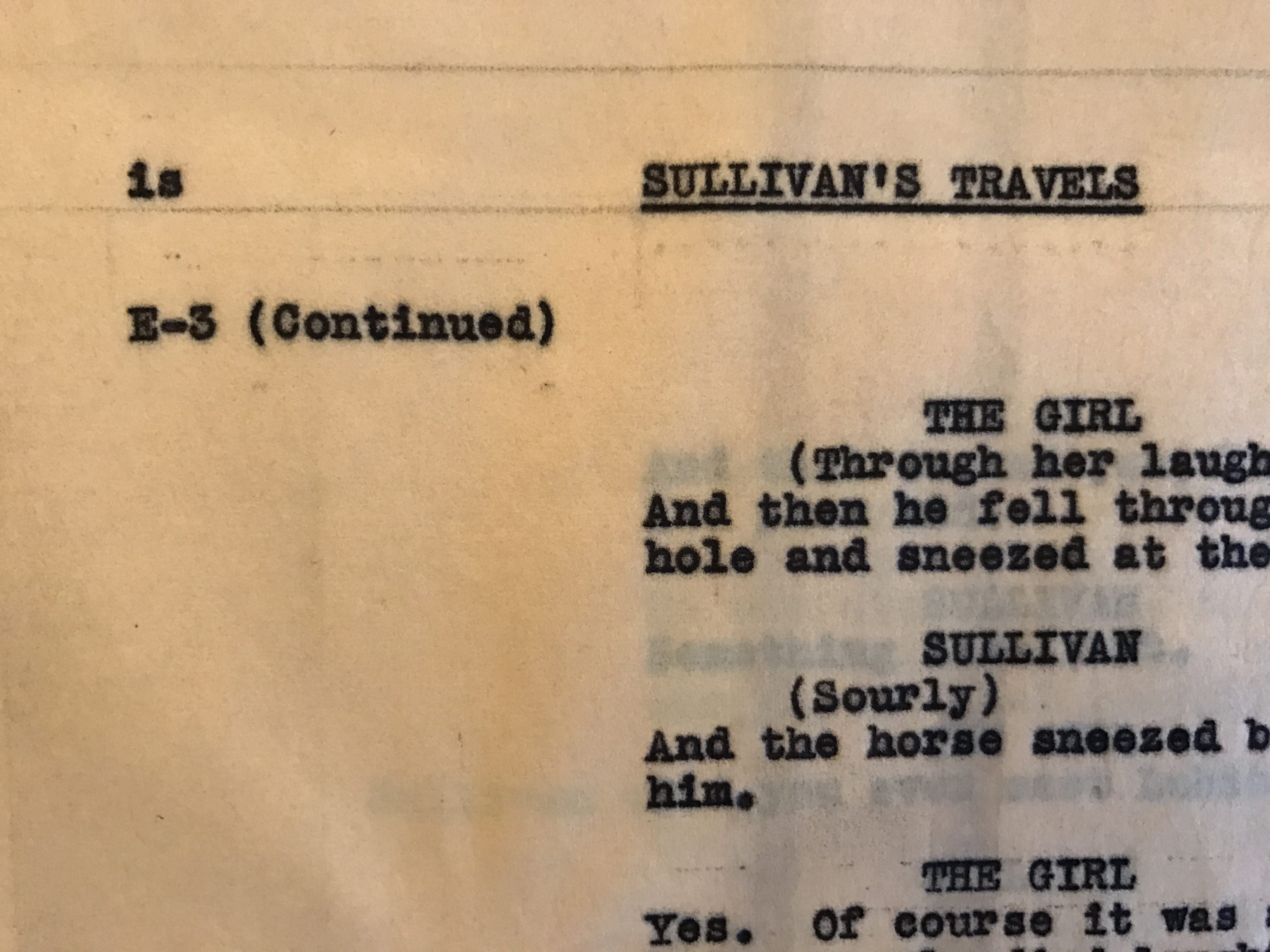

A bibliographical analysis of these drafts and others by Sturges shows how the Stenographic Department worked. At the top left corner of nearly each leaf of text (which appears on rectos only), the typist’s initials trace each sheet back to man or woman who typed it. For example, the initials “is” throughout Sequence A probably refer to Isabelle Sullivan, Sturges’ script supervisor for Sullivan’s Travels, which opened in 1942. The initials JA, EVG (probably Sturges’ personal secretary Edwin Gillette), LRR, and others appear on the pages in later sequences. At the top right corner, a system of hyphenated letters and numbers ordered the typed leaves within each sequence, and the script as a whole, respectively. The hyphenated number shows the leaf order within the Sequence, while numbers in parentheses below track the leaf count through the entire script. Dates were also typed at the bottom left to track the revision history of each leaf of the script across multiple drafts. The image below shows this system at work. In a draft of Sturges’ The Great Moment under it’s early title, Triumph Over Pain, leaves 6-8 in Sequence D (leaves 47-50 in the screenplay), are dated April 9, 1942, showing that two leaves of text were cut from a previous draft. Other pages in the same sequence are numbered 13a and 13b, indicating the addition of text, and dates show that these revisions were typed on April 13, four days after the D-6-7-8 revisions.

Revised draft script of The Great Moment under it’s original title, Triumph Over Pain. From the Robert M. Rubin Collection.

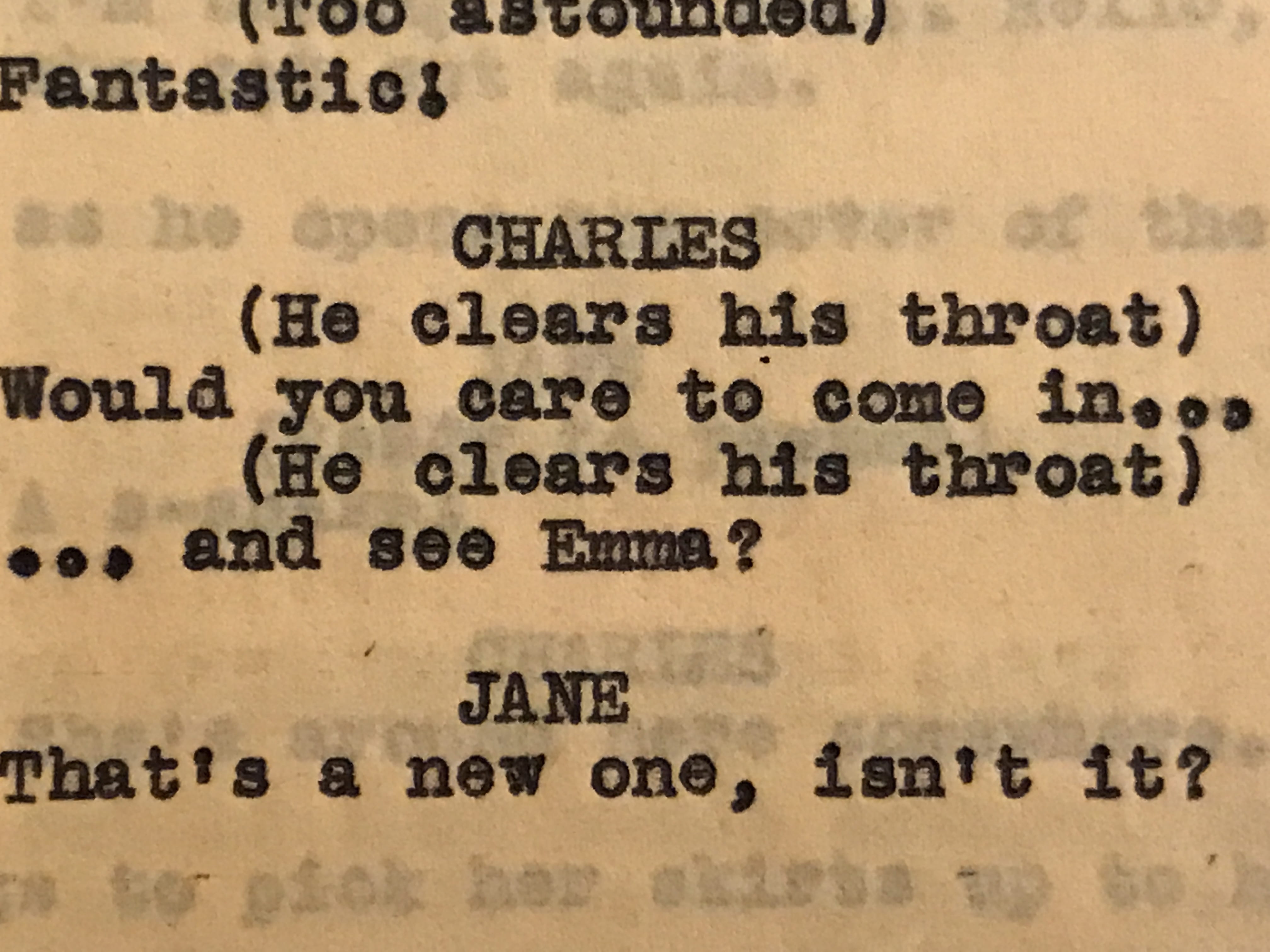

Typists and secretaries in the Stenographic Department were thus responsible for collating previous drafts and tracking changes throughout the development of the screenplay as document, and they relied and expanded upon centuries-old bibliographical systems to do so. Including their initials on each page recalls the use of press figures in English hand-press printing. The use of letters to distinguish one sequence of the film from the next also recalls the use of signatures in hand-press printing. Sturges omitted the letter J when numbering sequences, just as hand-press printers did when organizing a sequence of text. What’s more important, however, is that typographical evidence shows that drafts (or, proofs) of The Lady Eve screenplay were circulated in sections or small numbers. Just as a hand-press printer would issue a proof of a printed text for correction by an editor, a member of the stenographic department would type a limited number of copies of an individual sequence for distribution to the screenwriters, producers, and other crew for review. How do we know? The 1938-1940 draft of The Lady Eve is comprised of sheets printed in three different media. Portions of Sequence A initialled “is” are top-copy typescript, while most of the remaining sequences were produced on a mimeograph machine. The August 26, 1940 draft of Sequences A and B are carbon copy typescripts.

Above: Scripts in three different media. Clockwise from top left: The Lady Eve (typescript, top copy), Sullivan’s Travels (typescript, carbon copy) and The Lady Eve (mimeographed copy).

Unlike early printers, specialists in the Stenographic Department of a Hollywood studio had a range of technologies to choose from to most efficiently produce the requisite number of copies of a text at any given stage of the editorial process. A top-copy typescript functions much like a manuscript; the typewriter produces a unique copy of the text for distribution to just one person. Carbon paper was used to create up to five copies, for circulating the same text to a small number of people. If more than five copies were needed, or if a text had been stabilized to the point that it would be reproduced again and again for incorporation into subsequent drafts, a mimeograph stencil created a master copy of the text; one stencil could produce up to 1000 copies and, like standing type in a print shop, printed over and over again.

Typists were not simply taking dictation, or printing up a screenwriter’s handwritten notes on a text. They were skilled technicians who operated a variety of complex mechanical systems for producing texts, much in the same way that sound engineers operated a range of specialized equipment on the set. An in-depth knowledge of machinery and supplies, in addition to graphic standards and the distribution requirements of the printed document, were required to produce an acceptable script. (Even with the advent of modern word processing technologies, many of us struggle with setting tabs and margins; imagine doing this on a typewriter in a room full of click-clacking machines with carbon and onion skin paper.) It is also clear that members of the Stenographic Department worked closely with screenwriters and directors, though as yet I haven’t been able to nail down the copy editing skills required of someone working with screenplays rather than printed publications or personal communications.

Unfortunately, secretarial manuals and narrative accounts of Hollywood studios document not only the technical skills of female typists and secretaries, but also the extent to which they faced sexual harassment and discrimination in the workplace. Manuals often prioritized social skills for female typists, underplaying their specialized technical and linguistic prowess. Scripts, however, show the extent to which they engaged with the texts they produced. Tracking changes across multiple drafts and collaborating with individuals across departments within the studio required a deep knowledge not only of a film narrative and its development over time, but also of the work done by so many other specialists. Like the editors in a publishing house, or compositors in an early modern print shop, typists in the 20th century Hollywood studio were deeply engaged in rigorous, technical, creative, and mentally stimulating work.

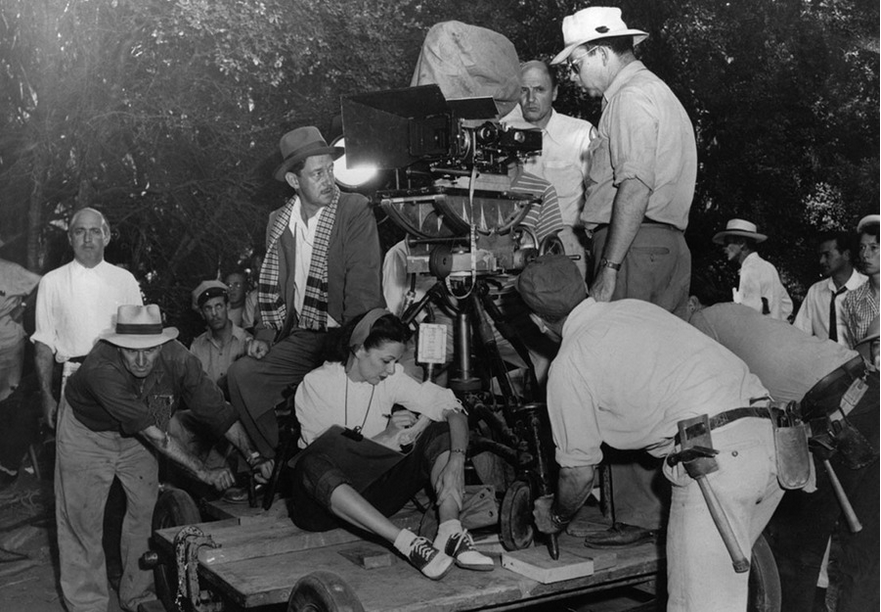

On the set of Sullivan’s Travels, script supervisor Nesta Charles or Isabelle Sullivan sits below screenwriter/director Preston Sturges. Images courtesy of the wonderful Script Supervisor Tumblr.

Leave a Reply