by guest contributor Edmund G. C. King

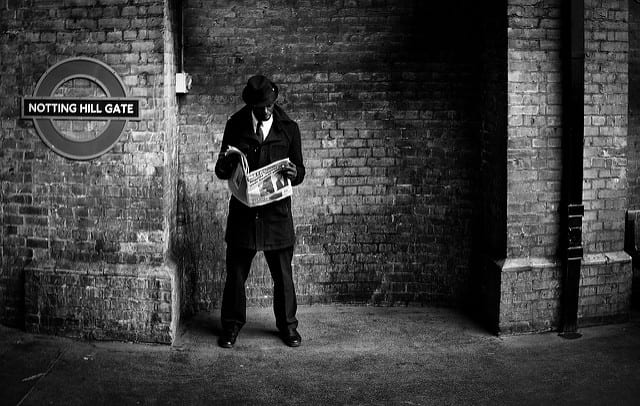

It’s just after 10 am on a dingy December morning in London as I approach Canada Water underground station. The morning rush hour crowds have receded, leaving only their wet footprints on the platform leading into the station. The outside sheet of a copy of this morning’s Metro, the free London commuter newspaper, has been pulped and trodden into the pavement near the entrance. A single word of the front-page headline is still legible: “Aleppo.” Inside, I walk down the escalators and turn right, onto the westbound Jubilee Line platform. A train arrives almost immediately. I get into the first carriage and stand inside the doors facing away from the platform. To my left there are twelve people sitting, facing each other in two rows of six. Exactly half of them are reading. A woman scrolls through her Facebook newsfeed on an Android phone. A couple in their 30s read copies of The Metro. Opposite them, an older man is skimming an article in the personal finance section of a tabloid newspaper headlined “The Hell of Middle Age.” Two women sit opposite each other, each absorbed in a book. One is reading management theory. The other has a thick, tattered pop-psychology paperback with subsections headed in bold and diagrams illustrating interpersonal relationships. Next to them, a woman sits, headphones on, reading a Spanish novella. No one in the carriage acknowledges the existence of anyone else, not even the couple with their matching copies of The Metro. Each reading surface has become what Erving Goffman calls an “involvement shield,” a way of demarcating personal space and signalling social “non-accessibility” in a shared environment. Seats free up at Southwark. I take one, pull out my iPhone, put my headphones on, load up Spotify and a cached copy of a Jacobin article, and prepare to immerse myself in my own media cocoon.

For the past year, I have been Co-Investigator on an AHRC-funded project, “Reading Communities: Connecting the Past and the Present.” The purpose of the Reading Communities project was to reach out to contemporary reading groups in the United Kingdom and encourage them to engage with the historical accounts of reading in the Reading Experience Database. But the experience of working on a project like this has also changed my own academic practice as an historian of reading. I find myself paying more attention to the everyday scenes of reading unfolding around me than I might have done otherwise, looking for the elusive connections between reading practices and reading communities in the past and the present. Of course, a random collection of readers in a London tube carriage does not in itself constitute a “reading community.” We, in our Jubilee Line media cocoons, might all be using books and other forms of reading material in avoidant ways, as coping mechanisms to deal with the intensities and demands of occupying shared spaces in a large city. Some of us may even be consuming the very same text—this morning’s Metro—simultaneously. These acts of textual consumption form part of our social imaginary; they are props for performing our roles as commuters and as Londoners. But simultaneity and a shared habitus are not sufficient in themselves to bind us together into a specific reading community. For a reading community to exist, the act of reading must be in some basic way shared. Readers need to interact with each other or at least identify as members of the same reading collective. The basic building blocks of a community are, as DeNel Rehberg Sedo observes, a set of enduring and reciprocal social relationships. Reading communities are collectives where those relationships are mediated by the consumption of texts. But how can we define the social function of reading communities more precisely? What relationship do they have with other communities and social formations beyond the realm of text? What can examples taken from historically distant reading cultures tell us about the social uses of shared reading experiences?

In Readers and Reading Culture in the High Roman Empire, William A. Johnson interrogates ancient sources for what they can reveal about reading and writing practices in elite Roman communities. The scenes of reading preserved in ancient sources provide detailed glimpses into the place of shared reading and literary performance in daily life. In Epistle 27, Pliny describes the daily routine of Titus Vestricius Spurinna, a 78-year-old retired senator and consul:

The early morning he passes on his couch; at eight he calls for his slippers, and walks three miles, exercising mind and body together. On his return, if he has any friends in the house with him, he gets upon some entertaining and interesting topic of conversation; if by himself, some book is read to him, sometimes when visitors are there even, if agreeable to the company. Then he has a rest, and after that either takes up a book or resumes his conversation in preference to reading.

In the afternoon, after he has bathed, Spurinna has “some light and entertaining author read to him,” a ritual house guests are invited to share. At dinner, guests are entertained with another group reading, “the recital of some dramatic piece,” as a way of “seasoning” the “pleasures” of the evening “with study.” All of this, he writes, is carried on “with so much affability and politeness that none of his guests ever finds it tedious.” For Johnson, this reveals Pliny’s belief that shared literary consumption forms a necessary part of high-status Roman identity. “Reading in this society,” he writes, “is tightly bound up in the construction of … community.” It is the glue that binds together a range of communal practices—meals, exercise, literary conversation—into one unified whole, a social solvent that simultaneously acts as an elite marker. Shared reading experiences in this milieu are a means of fostering a sense of group belonging. They are ways of performing social identity, of easing participants into their roles as hosts and house guests, clients and patrons.

Another externality that impels the formation of ancient Roman reading communities is textual scarcity. To gain access to texts in the ancient world, readers needed social connections. Literary and intellectual culture in such a textual economy will necessarily be communal, as both readers and authors depend on social relationships in order to exchange and encounter reading material. As Johnson shows, the duties of authorship in ancient Rome extended into the spheres of production and distribution. Genteel authors like Galen retained the scribes and lectors who would copy and perform their works for a wider coterie of friends and followers. This culture of scarcity in turn imprinted itself onto reading practices. In the introduction to his treatise On Theriac to Piso, Galen describes visiting Piso at home and finding him in the midst of reading a medical treatise, an act of private reading that readily segues into an extended social performance for Galen’s benefit:

I once came to your house as is my custom and found you with many of your accustomed books lying around you. For you do especially love, after the conclusion of the public duties arising from your affairs, to spend your time with the old philosophers. But on this occasion you had acquired a book about this antidote [i.e., theriac] and were reading it with pleasure; and when I was standing next to you you immediately looked on me with the eyes of friendship and greeted me courteously and then took up the reading of the book again with me for audience. And I listened because the book was thoughtfully written … And as you read … a great sense of wonder came over me and I was very grateful for our good luck, when I saw you so enthusiastic about the art. For most men just want to derive the pleasure of listening from writings on medicine: but you not only listen with pleasure to what is said, but also learn from your native intelligence …

As Johnson notes, this passage is striking precisely because of its unfamiliarity, for what it says about the gulf that separates “Galen’s culture of reading” from “our own.” Specialised texts in the Roman world were so scarce—and hence so valuable—that it was axiomatic to readers like Piso and Galen that the “good luck” of mutual textual encounter should be maximised by an act of shared reading, not simply of a small extract, but of the entire work. The result is a precisely described scene of reading that baffles us with its strangeness. What these anecdotes indicate is not only that, as Robert Darnton puts it, “reading has a history,” but that reading communities everywhere bear the unmistakable imprints of that history.

In early Victorian London, juvenile pickpockets reacted in their own way to the externalities of textual scarcity. As Henry Mayhew records, literate gang members would read their copies of Jack Sheppard and the Newgate Calendar aloud in lodgings during the evenings to those in their networks who couldn’t read. These acts of shared reading not only fostered group identity, but enabled gang members to maximise their communal resources, to make literacy and textual possessions go further. The reading communities in early twentieth-century New Zealand that Susann Liebich has studied are similarly embedded in wider networks of friendship and group belonging. Sharing books and reading tips was, as she demonstrates, a means of “fostering connections,” a way for “readers to connect with each other and with a world beyond Timaru.” What each of these examples shows is that the social function of shared reading differs according to the needs and norms of the wider communities and cultures in which that reading community is embedded. At the same time, however, attending to these differences encourages us to consider what is distinctive about norms and practices within contemporary reading communities, helping us limn what Rob Koehler elsewhere on this blog identifies as “the intimate and complex relationships between individuals, texts, and lived experience” across time and space, within history and our own present moment.

Edmund G. C. King is a Research Fellow in English Literature in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at The Open University, UK. He works on the Reading Experience Database and is currently researching British and Commonwealth reading practices during the First World War. He is co-editor (with Shafquat Towheed) of Reading and the First World War: Readers, Texts, Archives (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

1 Pingback