by contributing editor Carolyn Taratko

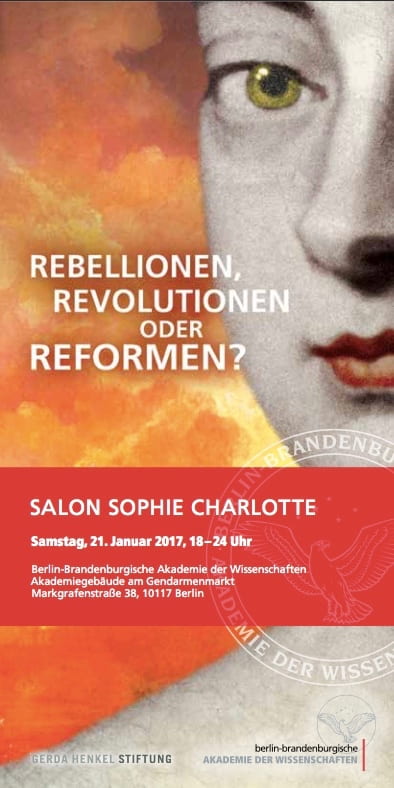

The Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities held its Salon Sophie Charlotte last weekend, an annual event during which the academy opens its doors to the public for an evening of guest discussions, presentations, and performances. This year’s theme, “Rebellion, Revolution, or Reform?” seemed especially prescient in our uncertain times and it did not fail to draw a crowd. (True to form, a spontaneous occupation of the stage by Berlin students defending the recently-terminated contract of a professor transpired, resulting in a shouting match between the occupiers and some tweed-clad members of the back row.) The mix of academic experts, artists, and the public made for a stimulating event, revealing perhaps the best of all possible worlds in which academics can engage the public with elements of conceptual history that have deep resonance today.

The role of music in times of rapid change surfaced in several venues throughout the evening. The tone was set for the evening by actress and singer Hanna Schygulla, who performed songs of resistance (among them the song of Italian anti-fascists in the 1940s, “Bella Ciao,” and “Ein Pferd klagt an,” a Brecht/Eisler classic). A conversation between Nike Wagner and Gerhard Koch and moderated by Ernst Osterkamp explored the role of music in revolution. Koch asserted that the performance of Daniel Auber’s opera La muette de Protici catalyzed the revolution in Belgium in 1830, during which the audience members burst forth from the theater and into the streets. Wagner offered a more tempered view, claiming that music could never assume the role of a revolution, but that without music, no revolutions could take place. Music, she continued, was not inherently revolutionary in a political sense, but could always take on this quality. The side-by-side quality of Auber’s artistic production and the revolutionary actions opened up the questions of whether the opera was causal, or if it had tapped into the prevailing mood.

The role of music in times of rapid change surfaced in several venues throughout the evening. The tone was set for the evening by actress and singer Hanna Schygulla, who performed songs of resistance (among them the song of Italian anti-fascists in the 1940s, “Bella Ciao,” and “Ein Pferd klagt an,” a Brecht/Eisler classic). A conversation between Nike Wagner and Gerhard Koch and moderated by Ernst Osterkamp explored the role of music in revolution. Koch asserted that the performance of Daniel Auber’s opera La muette de Protici catalyzed the revolution in Belgium in 1830, during which the audience members burst forth from the theater and into the streets. Wagner offered a more tempered view, claiming that music could never assume the role of a revolution, but that without music, no revolutions could take place. Music, she continued, was not inherently revolutionary in a political sense, but could always take on this quality. The side-by-side quality of Auber’s artistic production and the revolutionary actions opened up the questions of whether the opera was causal, or if it had tapped into the prevailing mood.

Another banner session, “Is Europe too old for revolutions?” featured a mix of political practitioners and historians. The provocative title referred to the demographic trend in western Europe, which is home to an ever-growing aging population, but also to the enshrined traditions, behaviors, and comforts that might make a revolution impossible, or at least highly undesirable. The panel, moderated by historian Etienne François, featured ‘68er and later German Vice Chancellor and Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer alongside activist Jutta Sundermann and political scientist Herfried Münkler. François led off by asking what it meant to have a revolution, and if it was still possible in Europe today.

A packed room prevented a decent picture of the panel “Is Europe too old for revolution?” (photo C. Taratko)

The practitioners (that is, Sundermann and Fischer) were critical of the term. Sundermann claimed that she no longer used the word and suggested that it perhaps belonged to previous generations. This was by no means to say that she and her contemporaries were no longer engaged for change, but that “revolution” was too abstract and perhaps carried with it too much negative baggage. Fischer was also skeptical. He insisted that political will is a prerequisite for change, but that it was better focused on institutions and laws that might need improvement. In light of his own peregrination from the Frankfurt left scene of the ‘60s to the corridors of power as a member of the Green Party, his response came off as typically distanced from his youthful roots.

“Revolution,” wrote Reinhart Koselleck, ”is a term now in vogue, but it is perhaps more raddled than its users’ would like to believe.” Is it the case that revolution in Europe is a romantic notion kept alive by academics and the vestiges of the student movement that live on in German universities? François felt confident that revolution was no longer Marx’s “locomotive of history” but instead was a common term in conversation, somewhat banalized and used as a descriptor for incremental change.

While the panelists seemed to take for granted that revolution was essentially modern, Münkler provided a brief conceptual history of the term. For him, its history begins with the Dutch throwing off Spanish control. The Dutch may have been the first, but it was the the German peasants’ revolt counted as the first people’s revolution, an important development that has since become an intrinsic part of the idea. The idea that change could bubble up from below, was, according to Münkler, new. Social change and the empowerment of lower classes gradually crept into the concept and took up residence there.

Münkler offered a perspective from the longue durée, one that was less interested in the immediate circumstances and effects than the overall conceptual history of the term. Others, especially Fischer, highlighted the highly-specific conditions under which revolutions, such as those experienced in France or Russia, took place. These stories of increasing tension led to a breaking point. In this sense, he argued, there was no paradigmatic revolution. Fischer closed with a sort of plea: he insisted that large political shifts are now outdated; if one looks at the past century, one can see the price of the German social state and how valuable it is, and that it should not be dismantled but carefully adjusted. For him, the “revolutionary tasks” that remained were in technology and nature.

Predictably, the consensus here leaned towards the improbability of another revolution in Europe. The Salon Sophie Charlotte provided a forum for a discussion of revolution as a diachronic concept, but also as a practice. The possibility for further political and social revolution was dismissed. Instead stability, and a desire to institutionalize the hard-won principles of earlier revolutions, seemed to guide the speakers. I wonder if perhaps the concept, at least as the panelists (all roughly of the same generation and somewhere on the left of the political spectrum) had framed it, has lost its purchase on reality. The music, it must be said, had not.

Leave a Reply