by contributing editor Eric Brandom

As insipid slogans of dubious provenance go, “be the change you wish to see in the world” is not so bad. On a bumper sticker or the signature line of a well-meaning colleague’s email, it is presumably meant to inspire. If it registers at all, it manages only to scold. The idea is not a new one, although it is also not ancient. In any case it is unsurprising that moral reform of the self should seem a good place to begin at a moment when many people who have not recently or perhaps ever thought about how to organize themselves politically are trying to figure out how to do so. With that complex of problems in mind, in this post I look back at a particular document, published in France in 1892, which served as a manifesto of sorts for a durable program of moral, and ultimately political, action. The Union for Moral Action, renamed the Union for Truth in 1904 and extant until 1940, engaged in we might now describe as advocacy and agitation, but was above all a venue for clarifying discussion. It was founded in the context of concern with the disintegration of social bonds—the social question—and emerged strengthened in unity and purpose from the great trial by fire that was the Dreyfus Affair. Paul Desjardins, a young literary-critic-turned-reformer, was the animating spirit of the Union, which in the end was a locus of progressive activity: Dreyfusard, solidariste, and concerned about the political status of women.

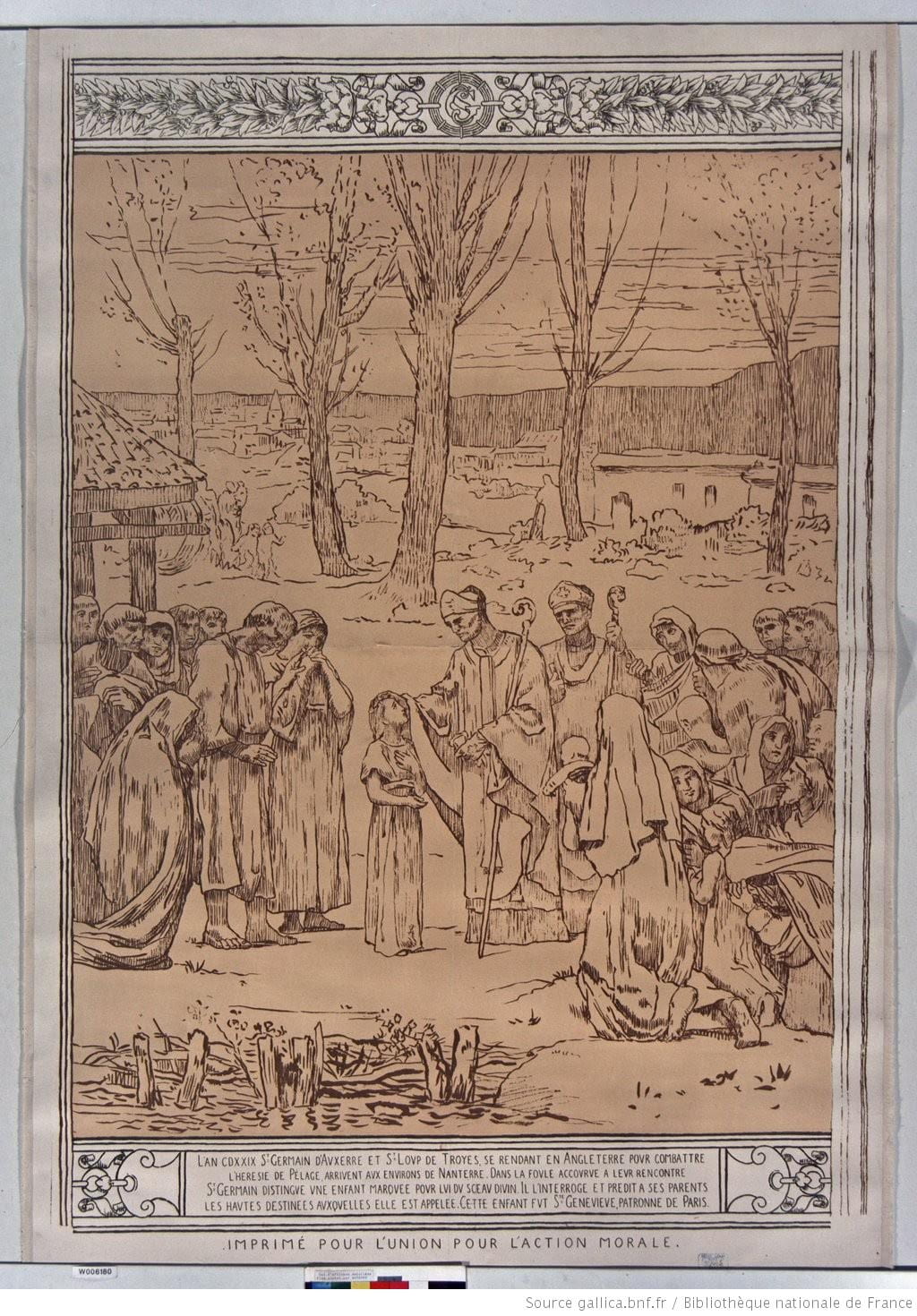

Puvis de Chavannes, Scene from the Life of Saint Genevieve, patroness of Paris – Printed for the Union for Moral Action, 1898 (BnF)

My object here appeared as an unsigned text in a summer number of the Revue bleue, with the unassuming title “Simple notes for a program of union and action.” Desjardins signed a brief paragraph introducing the manifesto, suggesting that he had solicited it and hoping that some people, at least, would find their own ideas reflected therein. In fact Jules Lagneau, Desjardin’s philosophy teacher, wrote the text and it would later be reproduced under his name in the Union’s Bulletin.

The first person plural rules the “Simples notes,” which are divided into three sections: our spirit, our rule, our action. “The weakening…of the social bond” is both a cognitive and a moral problem, and therefore the spirit of the Union is reason. This is not individuating reason, but rather, “a principle of order, union, and sacrifice…the ability to pass beyond one’s self while affirming a higher law, the idea of which man finds within himself and only the reflection outside himself.” The group is open to all who have “practical faith” but especially to those “without positive faith…who believe that in man, the spirit must command and not serve, because it alone has in itself its end and meaning, and that life has no value except where spirit has marked it.” The Union, then, welcomes all for whom truth and certitude are something one does not arrive at once and for all, but that are sought constantly.

The Union will not simply be one of good will, but rather one in which a certain minimal agreement of principle is constantly shaped and refined through action: “We are the beginning of a society that expects progress only through determination and the rigor of its principle: we tend to realize unanimity, we do not pretend to start from it.” Fanaticism will be avoided by constantly testing in life one’s ideas, which become mere words when they cease to be “the expression in action of interior freedom [l’expression en acte de la liberté intérieure].” If we act in everyday life in a way consistent with this principle, then “it matters little who brings truth to light, who brings salvation… What deserves to be will be.” This is not irenic faith in progress. There is no easy convergence of good intentions here, but rather a Pascalianism, perhaps of the left, which valorizes “discipline” and “renouncement” and wishes to teach “the unavoidable necessity of suffering… to combat false optimism… [and] the faith in salvation through science alone and through material civilization, lying mask of civilization, [a] precarious external arrangement that cannot replace intimate agreement.” Above all, the immoral idea that “the goal of life is to freely enjoy” must be met with the counter-example of the Union itself, which must model, as we might say now, good and social behavior: “For the people is what we make it: its vices are our vices, looked upon, envied, imitated, and it is right if they come back to us in all their weight.” The union must therefore offer “résistance réfléchie” to popular fashion, and rely on moral authority rather than popularity. “We forbid ourselves irony,” and prefer “un gaieté sérieuse.” We will be, the manifesto declares, simply as we are, without false modesty, pedantry, or pride.

Through a “pure and active charity” the Union will “save l’esprit publique.” And this is not a metaphorical charity, but rather one that, by setting aside the desire to save, hopes to create “the material conditions for morality.” The Union understands that impersonal charity corrupts, but individual and direct interpersonal charity “will be the vehicle of love, the spark that wakes the flame… In true charity, the one who receives merges with the one who gives.” True charity allows the spirit to rise above the immediate “sensible” good, and carries the spirit “infinitely higher through the contagion of love.” Acting first of all on those who are closest to us—and this is the most difficult—we make them happy by “unburdening them of their egoism and putting our love in its place. To make one’s self loved by loving with a male love that is absolute will, which is to say sacrifice, and in this way to learn to love—this is everything.” And the circle of love will expand—along the rails laid down by the division of labor: “the chain of necessary service is the link forged by nature between hearts and the divine path of charity through which we enter into to the soul of the people.” Thus we will create “progressively, naturally, an inner society founded on love, peace, and true justice, within an exterior society founded on interest, competition, and legal justice.” Such an operation requires, first of all, self-abnegation from those who wish to bring it about. In the end, the only model available is a monastic and revolutionary one: “an active Union, a militant laïque Order of private and social duty, living kernel of the future society.”

Demonstration at the place Gambetta in Carmaux, (late 1895) (Archives de la ville de Blois)

Lagneau’s program is a remarkable one in several ways. It traces a circle from the idea of law as such to the instantiation of law in a quasi-monastic order that would effect change in society by disciplining itself—is this a pre- or an anti-sociological approach to social change? More, in as much as we have to do with a democratic movement here, it is a moral rather than a political one. François Chaubet, historian of the Union, identifies Lagneau’s frankly elitist position as spiritualist republicanism, although here it appears in idealist and not materialist form. Action and even articulation was indeed clarifying: Lagneau’s manifesto drove the future maréchal Lyautey out of the original group, but Lagneau would not follow Jean Jaurès to the workers at Carmaux, and so himself split from the Union when it resolved to support the strike there. Lagneau’s austere, aristocratic, and mystical project for moral action can speak directly to us only in fragments—reduced, that is, to decontextualized quotations like the one with which I began. It is certainly possible to read Lagneau’s manifesto as an example of intense desire—visible in so many places at that moment, and perhaps our own—to be a subject, rather than object of history. Yet I think we can better read it as a usefully wrong answer to questions that are still asked today. There is an unmistakable urgency in his prose, and the moral urgency of truth as an ongoing collective project, grounded in collective action, is surely one we still feel.

Leave a Reply