by contributing editor Yitzchak Schwartz

In his seminal 1928 essay, “Ghetto and Emancipation: Shall We Revise the Traditional View?,” historian Salo Wittmayer Baron argues against what he refers to in his later work as the “lachrymose conception of Jewish history.” In the essay, Baron, at the time a young historian (albeit one with three doctorates), argues that his forbears in the Jewish academy, men such as Heinrich Graetz and Leopold Zunz, had overstated the extent of Jewish suffering in the premodern world. Although the Jews had faced certain disadvantages during the medieval and early modern periods, Baron argues, their status reflected that of a corporate community in a society of corporate communities, each with its own disadvantages and privileges. Baron would go on to become the most influential Jewish historian of the twentieth century, and perhaps even in the entire history of the field. His anti-lachrymose approach, codified in his own 18-volume “Social and Religious History of the Jews,” has framed the subsequent near-century of Jewish historical scholarship, leading scholars of Jewish history to focus on coexistence over conflict and on the positive over the negative in the Jewish past and Jewish-dominant-cultural relations.

Historian Salo Baron testifies at Adolph Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem.

In the last decade, however, Baron’s model has come into question, as several scholars have argued that Jewish historians have gone too far in trying to paint a non-lachrymose picture of Jewish past. The first scholar I am aware of to explicitly challenge this model is historian David Engel. In his 2010 Historians of the Jews and the Holocaust, Engel tackles the question of why Jewish historians rarely incorporate the Holocaust into their narratives and theories of Jewish history. This remains the case even as it is central to German and European history and has generated the field of Holocaust Studies. Engel traces this puzzling reality to Baron’s anti-lachrymose model, which has resulted in Baron’s intellectual heirs painting the Holocaust as a “black box” in Jewish history, an aberration that they do not allow to color how they see the Jewish past before and after it. Indeed, Engel demonstrates, many Jewish historians are very frank about this and explicitly argue that the Holocaust ought not to color our non-lachrymose view of Jewish history, citing Baron as their inspiration. This is despite the fact that Baron himself urged—as both Engel and Baron’s biographer historian Robert Lieberlis note—that the Holocaust necessitated acknowledgement of the darker sides of the Jewish past.

In a 2012 essay, historian Steven Fine makes a similar argument for a less anti-lachrymose approach to Jewish history, specifically with reference to late antiquity. In the article “The Menorah and the Cross: Historiographical Reflections on a Recent Discovery from Laodicea on the Lycus,” Fine uses a column fragment found among the ruins of this ancient Roman city to question the anti-lachrymosity not just of Jewish history, but of late antique studies as well. The fragment features an etching of the menorah flanked by a palm frond and shofar, a common Jewish visual trope in the Roman Empire. Superimposed over the upper portion of the menorah is a large cross—evidence that at some point, in some reuse of this stone fragment, someone made an effort to Christianize it. Fine argues that this object speaks to a subject carefully avoided by most ancient Jewish and late antique historians, namely the violence that accompanied Christianization during this period. On the Jewish end, Fine traces this approach to Baron’s forceful arguments in his Social and Religious History for the goodwill between Christians and Jews in late antiquity, a perspective Fine sees as reflecting mid-twentieth century efforts to create a place for Jews in the American consensus.

The latest installment in this debate had the unlikely departure point of a recent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibition, Jerusalem: Every People Under Heaven, 1000-1400, on which I worked as an intern in the planning stages, showcases the role of the city in the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim visual arts of this period. Praise for the exhibition has been almost universal. In the weeks since it came down on January 8, a debate about its presentation of Jewish history has been ignited in an article published in the Jewish monthly Mosaic Magazine by Wall Street Journal and former New York Times critic-at-large Edward Rothstein. Rothstein is already well known to students of Jewish art history for his critical essay on Jewish museums’ curatorial approaches, published in Mosaic last year. In his essay on the Jerusalem show, Rothstein argues that its curators go too far in painting a picture of the city as a place of harmonious coexistence of Jewish Christian and Muslim cultures, especially with regard to Jews. Rothstein argues that although the exhibition assembles many artifacts that evoke the importance of Jerusalem in Jewish life, Jews were an extremely persecuted group during this period whose experience, especially in Jerusalem, dramatically undermines the exhibition’s narrative of diversity.

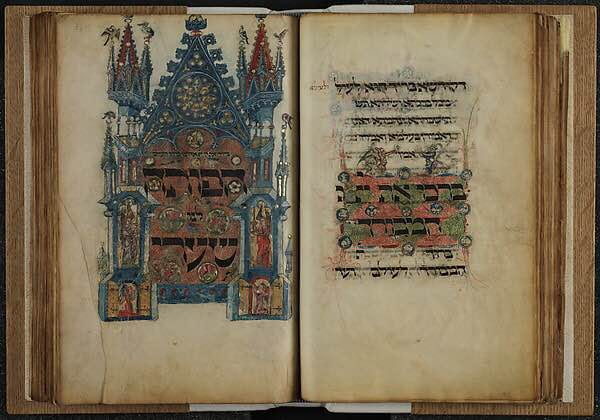

This page from a fourteenth-century illuminated Jewish prayerbook features a frame surrounding the plea from the Yom Kippur liturgy, “He who opens the Gates of Mercy” that evokes the gates of heaven and of the heavenly Jerusalem. Inasmuch as this work of art evokes a flourishing Jewish culture and Jewish longing for Jerusalem, however, it reflects the harsh realities of Jewish exile from the holy land.

In two responses to the article solicited by Mosaic, Fine and Robert Irwin, Middle East editor of the Times Literary Supplement, echo Rothstein’s assessment of the exhibition’s approach to its Jewish subject matter. Drawing from medieval traveler accounts, Irwin notes the obstacles Jews faced in the holy land during the middle ages and the difficulty many even had accessing Jerusalem. Fine traces the approach to art history evinced by Jerusalem to the work of eminent art historian Kurt Weitzmann, a dissident scholar who left Nazi Germany and settled at Princeton. In Fine’s reading, Weitzman’s 1979 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum The Age of Spirituality was one of the first to depict a harmonious coexistence of differing religious communities during the late antique period in galleries showcasing “The Jewish Realm,” “he Christian Realm,” “The Classical Realm” and so forth. To what degree was Weitzmann’s harmonious understanding of late antiquity, then, influenced by his own reality in postwar New York and his longings for Wiemar Berlin, Fine asks? To Fine, both Weizman and Baron’s visions, as well as those of many of their proteges in the curatorial and Jewish-historical professions respectively, have been deeply colored by their desire to create a more tolerant and multicultural society in their own times.

The debate over the role of lachrymosity in Jewish history should hold a lot of interest for Jewish historians. Although its been several years since Fine and Engel’s critiques of the anti-lachrymose approach, I do not know of any scholars that have followed their lead and worked to construct a post-anti-lachrymose narrative. What would such a narrative look like? Thinking of my own area of American Jewish history, such an approach to things might lead us to ask more questions about how anti-Jewishness has impacted American Jews, their senses of community, religious lives, and senses of themselves. This is a kind of question that is rarely asked in the field—indeed, as organizer and writer Yotam Marom points out in a recent article, it is almost a taboo subject in Jewish public discourse in general. The possibilities for a less, if not anti anti-lachrymose, Jewish history are many. As tempting as it is in politically trying times to use the past as a role model, the actual picture is perhaps much more rich and nuanced, even as it perhaps raises some troubling questions and realities.

February 23, 2017 at 5:30 pm

There was an AJS round table 3 years ago that addressed exactly this question. With E. Carlebach, Engel, and Adam Teller. I believe it was subsequently published in AJS review.

March 16, 2017 at 10:21 pm

Hey Jordan, Sorry I missed that comment! I remember hearing about the round table now that you mention it although I was not at AJS that year. Very cool!

December 18, 2018 at 1:23 am

I work on Jewish-Christian relations in medieval Iberia, and consider my approach anti-anti-Lachrymose. My first book is ”Jews and Christians in Medieval Castile: Tradition, Coexistence, and Change” (2016). The next book, on the 1391 Riots, will go even further. Thanks for writing this.

June 14, 2019 at 1:10 pm

Fascinating, looking forward to seeing it!