by Erin McGuirl

The story of the revival of Harper’s Weekly, a magazine published from 1857 to 1916 and then 1974 to 1976, begins with William (Willie) Morris. As Editor-in-Chief of the Monthly from 1967 to 1971, Morris changed the tone of Harper’s Monthly by publishing long-form, liberal-minded pieces by writers like Norman Mailer and William Styron. In 1971, magazine owner John Cowles, Jr. pressured Morris to take it easy, blaming his lefty writers for driving away advertising revenue. Morris refused, and much like the mass resignation of editors at The New Republic in 2014, many of Harper’s best writers, including Mailer, Syron, and Bill Moyers, walked out with him, leaving behind a lot of big shoes to fill.

Hired four months after Morris’s departure with his staff, Editor-in-Chief Robert Shnayerson (formerly of Time) needed to retain the interest of the new readership built up under his predecessor’s leadership without driving away much needed ad revenue. Enter Tony Jones, and a new section in the magazine: WRAPAROUND. First appearing in 1973, WRAPAROUND, edited by Jones, was a riff on the Whole Earth Catalog. In fact, there’s a direct link between the two, because Stewart Brand and the Catalog were the cover story of the April 1974 issue, and guest editor of WRAPAROUND. Like the Catalog, WRAPAROUND published reviews of tools for living and solicited content directly from it’s readers. “Above all,” Jones wrote in his first editorial, “the WRARPOUND invites your participation. …[We] would like you to think of these pages as an extension of your own processes of discovery, as a place to contribute whatever information, perspectives, resources, and conclusions you have found valuable in your own life – and share them with all Harper’s readers.” This is a page taken directly from the Whole Earth playbook. Stewart Brand and his team published regular Supplements to the Catalog that included content (fiction, poetry, and non-fiction) solicited directly from readers. Anyone could submit their own work for publication in both the Supplement and the Catalogs, and all printed contributors were paid for the work. And very much like the Catalog, each WRAPAROUND included an order form, so that readers could order anything they read about in the magazine directly from Harper’s offices.

From the Library of the New-York Historical Society.

WRAPAROUND must have been popular with reader/writers, because Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization was revived in 1974 using the one-year-old Harper’s segment as its model. Announcement of the weekly was something of a media stunt: Jones placed ads in local newspapers around the country similar to this full-page editorial/ad he published in The New Republic, explaining that he was reviving the Weekly, and he intended to exclusively publish content written by its readers. Here’s a summary of his intentions, in his own words:

“I want to offer a variety of communications from real people about just anything. … In a real sense, this communication would be a collection of points of view. A swath of our consciousness. An ongoing biopsy of our civilization. … So I’ve decided to revive the famous HARPER’S WEEKLY, a national newspaper that flourished concurrently with Harper’s Magazine from 1857 to 1916. The people who ran it had the temerity to call it ‘a journal of civilization.’ Well, that is exactly what I have in mind for the new Harper’s Weekly.”

As in the Whole Earth Catalog, writers would be paid for submissions that wound up in print; $25+ for features (a relative value of $116-140 in 2017 when calculated as labor earnings), $15 for items published in the “Running Commentary” section, $10 for “clippings, quotes, or other research material (please include primary sources.)”

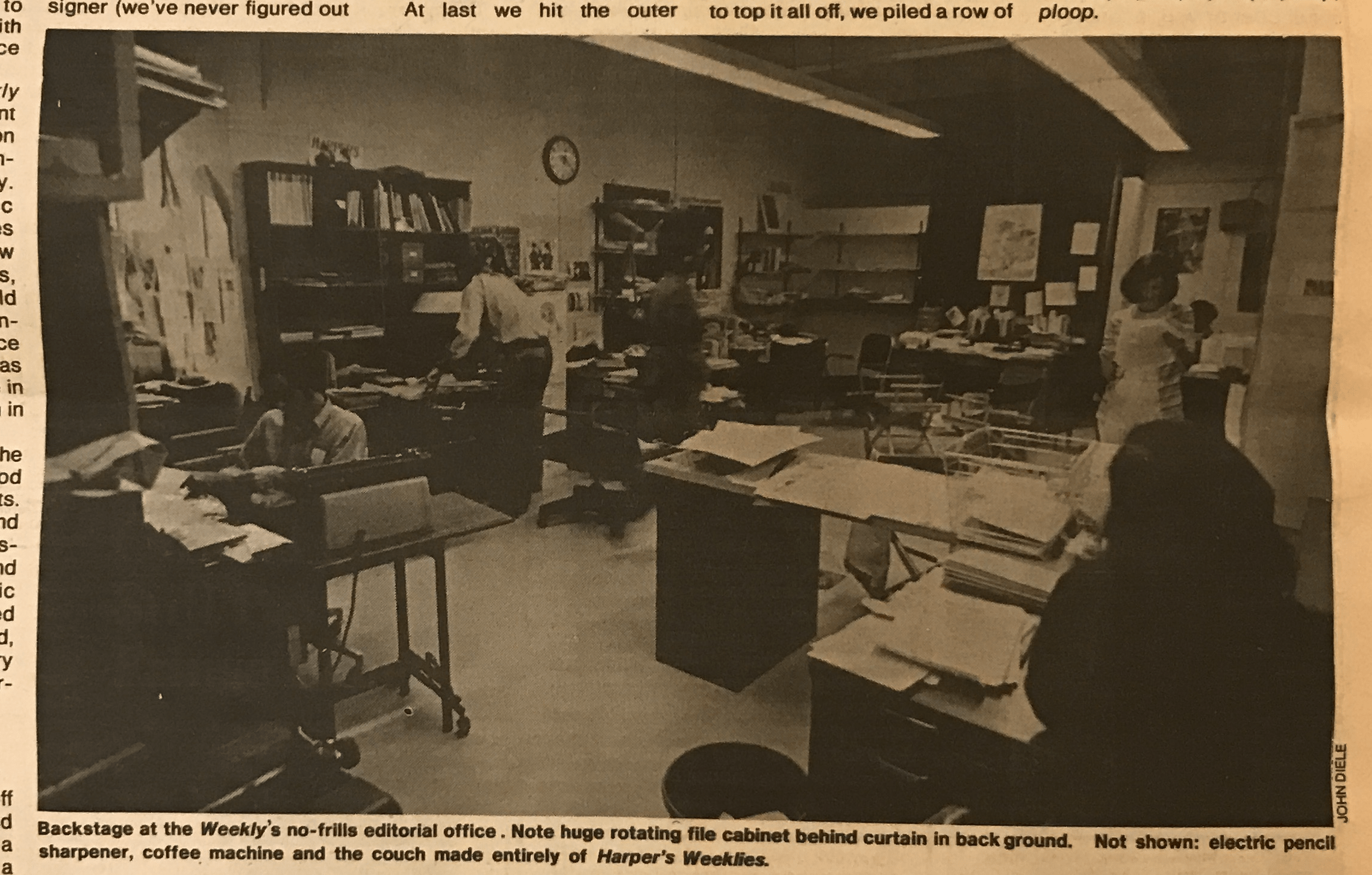

The Harper’s Weekly offices in New York, published in the magazine. From the Library of the New-York Historical Society.

Published from November 1974 to May 1976, the revived Harper’s Weekly is an extraordinary body of work. Readers from all over the country submitted more content than Jones and his team of editors could use (more on that in a minute), and the editorial board was in constant communication with its writer-readers through the printed magazine. In April of 1975, Harper’s Weekly published a frank editorial about its design, admitting that it had not yet achieved the quality and uniformity it aimed for. They published readers’ suggestions for improvement of the layout, logo, and typeface, and invited anyone to join their ongoing conversation. Perusing issues of the Weekly, one sees the staff working with new ideas – using larger typefaces, experimenting with heading styles and graphics, and moving regular sections from one page to another. Under Jones’ direction, however, they never abandoned the Harper’s Weekly 19th century masthead, and the paper’s tagline, “America’s Reader-Written Newspaper” always appeared in bold nearby.

The reader-contributed articles often focused on local or obscure issues. An issue highlighting the world of the American snake handler featured interviews with self-ordained Reverend Carl Porter of Cartersville, Georgia, snake handler Robert F. Wise, Jr. of Charleston, West Virginia, and William E. Haast, director of the Miami Serpentarium. Another reader, Robert Cassidy of Chicago, profiled Laurie Brandt and Julian Sereno in “Turning Words into Type,” an article describing their one-room typesetting business, Serbra Type. These young entrepreneurs were the compositors behind University of Chicago publications like Current Anthropology. The Weekly established regular departments, notably a Critics Corp that featured regular reviews of movies, books, records, television shows, organizations, and conferences. They even printed a Critics Card that readers could clip from the magazine and present at an event, and printed readers’ accounts of what happened when they tried using it. Alongside this diverse and unusual content – which is remarkably well written – the revived Weekly featured ads by major corporations. Mobil, the Bell Telephone Company, and Smith Corona all bought prominent space.

The journal reported on its operations in both issues of December 1975. The Weekly received 125,000 mailed submissions, and printed 3 million copies of the magazine for distribution by subscription and in newsstands. Jones and his team also published a remarkable account of its readership, including demographic information (gender, educational background, income, marital status, employment) gathered from a survey completed by more than half of the randomly selected sample of 2,000 subscribers (a response rate of more than 50% is remarkable), and compared that to information collected in similar surveys of subscribers to Time, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal.

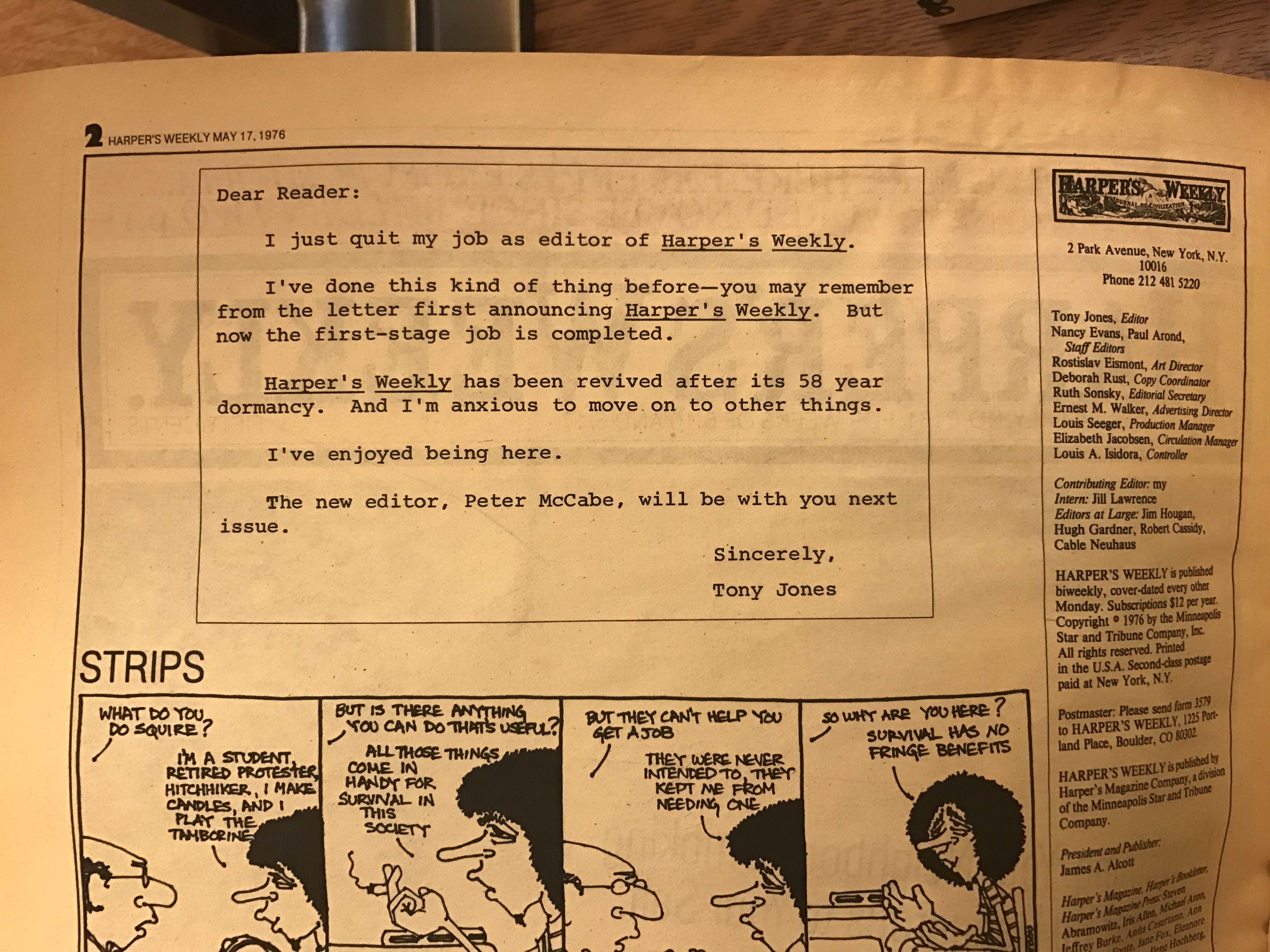

In 1976, however, something changed in the Weekly, and at Harper’s. That year, Lewis Lapham replayed Robert Shnayerson as editor in Chief, and the Weekly gradually declined and died. The issue for the weeks of May 10 and 17 appeared on newsstands without the historic 19th century masthead. The large photographic image on the cover, the typography, and the layout were unmistakably different from everything that came before it; most importantly, however, the “America’s Reader-Written Newspaper” tagline was conspicuously missing. A notice appeared on the first page of the paper:

Harper’s Weekly, Weeks of May 10 and 17, 1975. From the Library of the New-York Historical Society.

Inside the paper, long feature-length articles with prominent bylines replaced the shorter pieces. Peter McCabe, an editor at both Harper’s and Rolling Stone, took over as Editor of the Weekly, but it wasn’t the same magazine after Jones left because its core mission to publish the work of the common reader had been abandoned. The Weekly ceased publication sometime in the late summer or fall of 1976.

Those familiar with John McMillian’s Smoking Typewriters might read the revived Weekly as an outgrowth of the underground press movement, and the magazine itself certainly speaks to that. But the magazine itself was modeled on something that was also akin to, but not part of, the underground press. At a moment of crisis for a landmark American magazine, seasoned editors used the Whole Earth Catalog as a model for a new section of the Monthly, WRAPAROUND.The model worked, and Harper’s Weekly`was reborn in the wake of its success. This speaks not only to the impact of the Catalog across a broad spectrum of American publishing, but also, and most importantly, to the impact of its model on a growing body of readers who really wanted to access and exchange information. I see model as fundamentally bibliographic, and participatory. Within that framework, discovery (or the act of reading) engenders participation by a community of readers and writers sharing a printed resource about tools for living. In From Counterculture to Cyberculture, Fred Turner makes important connections between Stewart Brand and Whole Earth community, and the early days of Silicon Valley and the internet. By publishing its readers’ own writing and drawing them into the editorial process, Harper’s Weekly fostered a short-lived community of engaged participants with shared concerns who assumed the roles of critic, local historian, anthropologist, and activist, and then shared their experiences with a national audience through the magazine. This sounds a lot like what so many of us engage in online everyday as readers, blog writers, Tweeters… the list goes on. Harper’s Weekly is yet another example of the how the Whole Earth model took root in American information and popular culture, in the moment just before the dawn of the digital age.

March 21, 2017 at 10:47 pm

This is an extraordinary example of the continuity of bibliographic democracy–the sort of blurriness between writers and readers, authors and compilers, producers and receivers that has made early modern bibliography such a rich field for literary theorists in recent years. That this continues unabated–and with potentially subversive implications–into the latter half of the 20th century–is remarkable and exciting, and a point of continuity that both early modernists and modernists should definitely explore further. The Republic of Letters lives!

August 31, 2021 at 9:48 am

Very interesting