by guest contributor Michael Meng

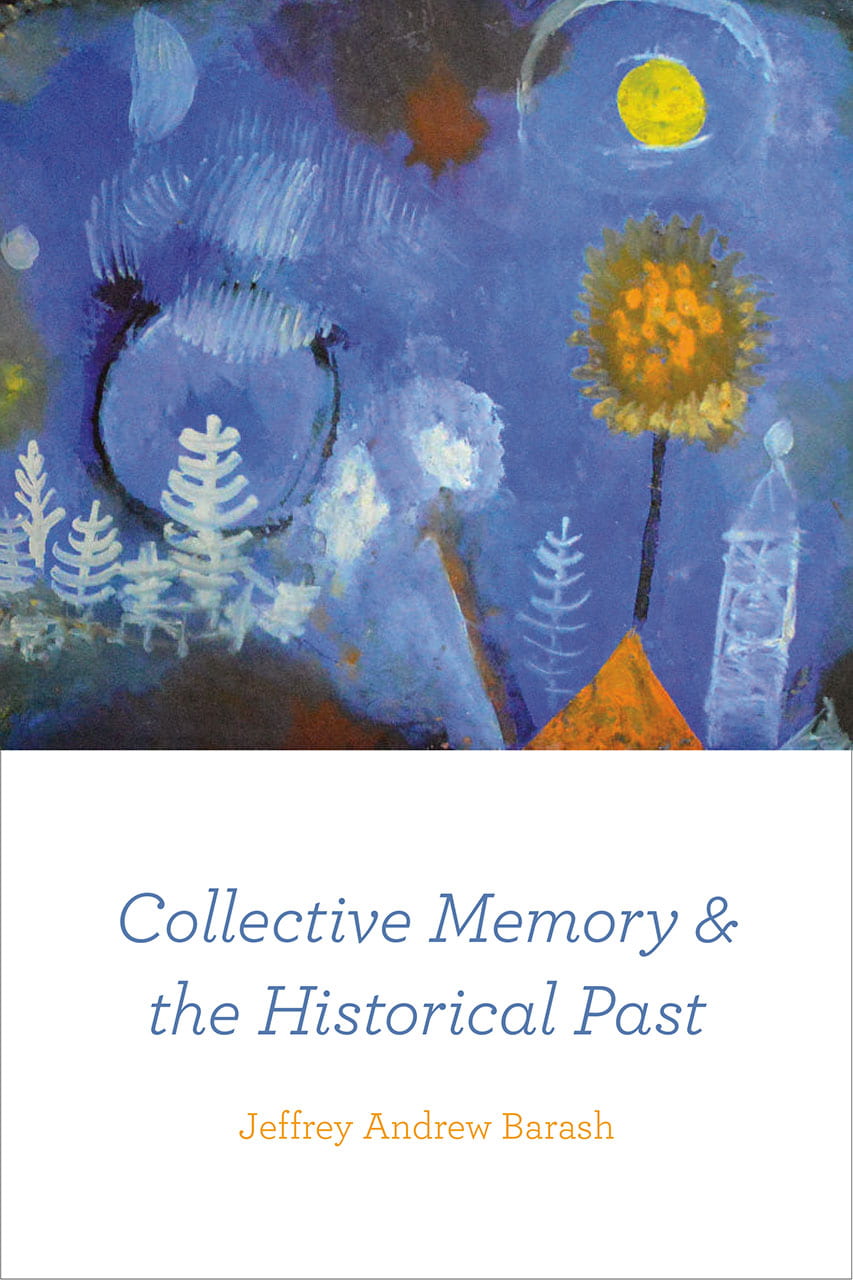

The JHI Blog is pleased to announce a new occasional feature, a forum bringing together faculty across disciplines to discuss recent works in intellectual history. The inaugural forum is devoted to Jeffrey Andrew Barash’s book Collective Memory and the Historical Past (University of Chicago, 2016).

Jeffrey Andrew Barash has written a highly insightful and erudite book on the complex relationship of the past to the present. Moving capaciously from the ancient period to the present, he addresses a wide range of issues regarding what it means to remember. Chapters include discussions on some of the central theorists of memory from Sigmund Freud to Maurice Halbwachs to Gerald Edelman; on the centrality of the image in twentieth-century mass media; on the reputed ‘skepticism’ of Roland Barthes and Hayden White in regard to the capacity of history to distinguish itself from fiction; and on the origins of “collective memory” as a theoretical concept to interpret the enduring “quest for stability and permanence” in the wake of twentieth-century challenges to metaphysics by Martin Heidegger and many others broadly influenced by him in post-1945 France (128).

Behind these different explorations lies, however, an ambitious attempt on Barash’s part to identify an “impartial” or “critical” space for historical reflection in the sociopolitical sphere of public life in which historical thinking unfolds. Barash defines the critical function of history in the public sphere mostly by what it does not do: history is most clearly different from mythic, ideological recollections of the past but also, if more subtly, from the emergence of the ostensibly human quest to imbue the past with a common meaning through the nourishing of what Barash calls collective memory. In what follows, I consider his attempt to identify a space for history independent from collective memory and myth. Beforehand I will briefly establish as Barash himself does the central dilemma at stake.

Plato (Silanion Musei Capitolini MC1377)

Barash astutely begins his book with Plato’s concept of anamnesis. In the Meno, Phaedo, and Phaedrus, Socrates suggests that anamnesis recalls in the present what was always already known by the immortal soul prior to embodiment. Recollection brings one back to the hyperouranian vision of eternal truth that the soul had before falling into this world of flux and death. The political consequence of Plato’s doctrine of anamnesis is significant as Hannah Arendt understood in her important essay on authority (Arendt, Between Past and Present, 91-141). Arendt discusses Plato’s attempt to establish a system of authority that would transcend the conflictual and violent life of the polis. According to her, Plato sought to establish the hegemony of reason in the person of the philosopher king as the possessor of the truth gained through anamnesis. The philosopher contemplates the ideas that “exist” in a realm beyond this world of uncertainty and change. The philosopher contemplates the truth, and the truth is unassailable precisely because it transcends the uncertainties, imperfections, and perspectivalism of finite human existence.

The collapse of this Platonic notion of truth since the late nineteenth century has opened up for Arendt and others the possibility of embracing time or contingency as the basis for a democratic politics of equality. The argument being this: if timeless truth cannot exist for mortals, then no one single person or group can claim the right to rule over another (Arendt, The Promise of Politics, 19; The Human Condition, 32). The lack of absolutes or indubitable foundations precludes any one view from becoming dominant—a community comes together in shared recognition of the fragility of any view. This anti-foundationalist notion of democracy has been embraced by a range of post-1945 thinkers from Theodor W. Adorno to Jan Patočka to Jacques Rancière. In what can be viewed as an important addition to this post-1945 conception of democracy, Barash suggests that history—including the one he writes—brings to public awareness the “group finitude” that subjects any given collective memory to “modification” (215-216). History also underscores the impossibility of ever bringing to full clarity the “opacity” of the past (105-106, 113, 170). Hence, history reveals the fragility and limits of memory as the collective product of mortals who cannot transcend the gap between past and present, since a holistic view of time eludes the “finite anthropological vision” (113).

A historical awareness of the finitude of collective memory proves especially important because it can undermine the ideological mobilization of collective memory for an exclusionary politics. One of the hallmarks of the radical right’s assertion of authority in modern European history has been the creation of myths about the alleged eternal homogeneity of the community whose interests it claims to represent. The radical right perpetuates a nationalistic memory that claims to be absolutely correct. By insisting on the fragility and limits of any collective memory, history challenges the ideological assumption that the past can be known with absolute certainty.

History also challenges ideological interpretations of the past in another way, as Barash shows in his gentle critique of Barthes and White’s portrayals of history as a form of fiction. In Barthes’ words: “Historical discourse is essentially an ideological elaboration or, to be more precise, one which is imaginary” (quoted in Barash, 179). While Barash appreciates Barthes’s and White’s challenge to naïve empiricism, their view is nevertheless “too extreme” for him (176). Many historians will probably agree, but I think it might be worth considering alongside Barash the deeper issue at stake here regarding the status of critical thought. Barthes’s deployment of the word ideology brings us back to the relevant nineteenth-century debate between British empiricists and German idealists over the question of whether reason is independent of history. Is reason universal and necessary? For Marx, a student of Hegel and Kant on this question, if reason is not universal and necessary, then it has to be conventional or ideological. And, if reason is ideological, then how can philosophy possibly fulfill its critical task? Herbert Marcuse lucidly summarized the issue in Reason and Revolution, writing that empiricism “confined men within the limits of ‘the given’” (Marcuse, Reason and Revolution, 20).

Barash’s project aims to rescue “critical” thinking from the conventions of the present as well but he does not do so through Hegel (177 and 216). How does he proceed? He locates a critical space for history by distinguishing it from myth, the central difference being that history relies on “the critical methods of reconstruction on a factual basis” (216). The historian builds a narrative partly from the facts of what happened. This view may sound like conventional empiricism at first glance, but it turns out not to be. To understand the nuance of Barash’s argument, we must ask a basic question: What is a fact? The strict empiricist claims that the facts are the unassailable truth that renders the authority of the historical narrative indisputable. The empiricist is an inverted Platonist who forgets the history of the fact. The word fact comes from the Latin factum, which means human actions and deeds. The facts are wrought by humans and that which is wrought by humans –– in the western metaphysical tradition at least –– has long been viewed as contingent beginning with Plato who views history as the study of the shadows of the cave.

Barash is not an empiricist in the traditional sense as just described. He strikes me as advancing what I might call a “contingent empiricism” –– an empiricism that strives to remain open to modification and change in full awareness of the temporality of one’s own exploration of the past. There is no Platonic escape from time in Barash’s account other than the “illusory” escape of myth (113). If there is no escape from history, if our perspective of what happened changes as we change and we change as we explore what happened, then the past cannot be grasped in a final or certain manner. The “opacity” of the past always withdraws from one’s temporal grasp. The only way to claim a final account of the past consists in turning the past into a constantly present thing that never changes.

If all is equally temporal, one might express worry that such a view leads to a vitiating relativism whereby every claim and behavior is equally justified. But this worry overlooks a central presupposition of critique. Any critical project, if it is to engage in an egalitarian exchange of reasons and is not to be mere apodictic Declaration (a “Machtspruch”), implicitly holds some value constant as the basis of the critique it offers. Returning to Barash’s book might illuminate the point. In the end, I see Barash as orienting history towards an affirmation of temporality or transience. The critical edge of such a view of history is not only that it challenges the mythic assertion of homogeneity but also that it undermines the ideological impulse to declare a secure and certain interpretation of our world. History disrupts certainty by affirming the complex condition of change that humans have struggled to make sense of since the ancient period. Ironically, history holds time constant as the basis of its critique of ideology and myth.

To conclude, let me return to my initial praise of Barash’s book. It raises a host of important questions about memory and history, while placing an important emphasis on history as an affirmation of the transience of human life. In this respect, I look forward to the exchange on his stimulating book.

The editors wish to thank Michael Meng for his graciousness in volunteering to write the inaugural post.

Michael Meng is Associate Professor of History at Clemson University. He is the author of Shattered Spaces: Encountering Jewish Ruins in Postwar Germany and Poland (Harvard, 2011) and co-editor of Jewish Space in Contemporary Poland (Indiana, 2015). He has published articles in Central European History, Comparative Studies in Society and History, Constellations: An International Journal of Critical and Democratic Theory, The Journal of Modern History, and New German Critique. He is currently writing a book on death, history, and salvation in European thought as well as a book on authoritarianism.

April 22, 2017 at 1:14 pm

Prompted by the interesting reflections made in the forum so far, I thought I might add three brief remarks to the conversation:

1: The anti-foundationalist notion of democracy that I ever so briefly introduced to which I think Barash’s book can plausibly be interpreted as making a contribution through his account of the impossibility of attaining a final, holistic view of the past presupposes equality based on the negative norm of the absence of the right of any one person or group to govern another. A democratic community comes together around the common assumption that a privileged place cannot be granted to any one view (or memory) in the absence of attributing final authority to any one person or group. If no one single way of viewing the world can claim to be absolutely certain in the absence of achieving a final view of the whole, then we might build a democratic community around the affirmation of limitation: we affirm the historical fragility of our own views and let go of the impulse to impose them on others in what amounts to a vain attempt to overcome the uncertain and vulnerable beings that each of us are. This notion of democracy is oriented towards critiquing assertions of certainty and therefore domination (e.g. an ideological or mythic view of the past deployed to assert domination of one group or constituency over another). It does not claim to offer a positive normativity other than the presupposition of equality that is not open to negation in a democratic community –– a presupposition that, to emphasize, it defends negatively. Jacques Rancière has perhaps developed this point most explicitly. As he writes in _Hatred of Democracy_: “Political government, then, has a foundation. But this foundation is also in fact a contradiction: politics is the foundation of a power to govern in the absence of foundation” (Verso, 2014, p. 49). Following Rancière, one could argue that negation plays an important role in sustaining a democratic society insofar as it undermines the belief in the absolute certainty of one’s own correctness as the basis of domination.

2: This egalitarian view of community stresses the commonality of uncertainty or vulnerability. It perhaps goes without saying that we are vulnerable in a number of ways (mortality being one). From this perspective, a number of philosophers have become increasingly attracted to the possibility of nourishing a compassionate and egalitarian community around suffering (e.g. the recent works by Judith Butler, Adriana Cavarero, and Todd May as well as that of their predecessors –– Arthur Schopenhauer, Emmanuel Levinas, and Theodor W. Adorno). In my view, one significant issue at stake in this turn to vulnerability is an attempt to find a way to attenuate the post-Hobbesian exaltation of self-interest that weakens solidarity and community.

Though Barash himself does not foreground the issue of suffering, his notion of “collective finitude” explicitly affirms sociality in contradistinction to Heidegger’s notion of authenticity.

3: Can one build an egalitarian community around suffering and/or the negative normativity of anti-foundationalist notions of democracy? Or does egalitarianism and solidarity need to be defended in an ostensibly more positive manner? And, if so, what might that positive vision be?

April 25, 2017 at 1:10 am

Thanks Michael, this is a really interesting development of your point. Firstly, for the historiographer, there would be histories (and communal memories) of such suffering, vulnerability, and the ways of coping that are developed in response to them to be investigated and written.

Secondly, it seems to me that it is the experience of suffering – of injustice – that often prompts the demand for equality. So that’s not wholly negative. Once again, and perhaps the historians can jump in here, but it seems that these demands are keystones in communal memory. Your third question seems plausible then, though perhaps we shouldn’t stress the negative/positive distinction overmuch.

Andrew