by guest contributor James Casey

On a chilly winter day in 1941 Jamil Sasson, a Syrian employee of the French Mandate bureaucracy, sent a letter to the Secrétaire général du Haut-Commissariat de la République Française en Syrie et au Liban to protest his termination and loss of pension. “Permit me,” Sasson wrote, to underscore the essential French “principle of equality for all.” (1/SL/20/150) This was not merely the protest of a disgruntled former employee: Jamil Sasson was a Syrian Jew who had lost his position in the civil administration of the French Mandate after the application of Vichy’s antisemitic laws to French overseas territories. Based on the records of his professional duties, it seems he was also a spy.

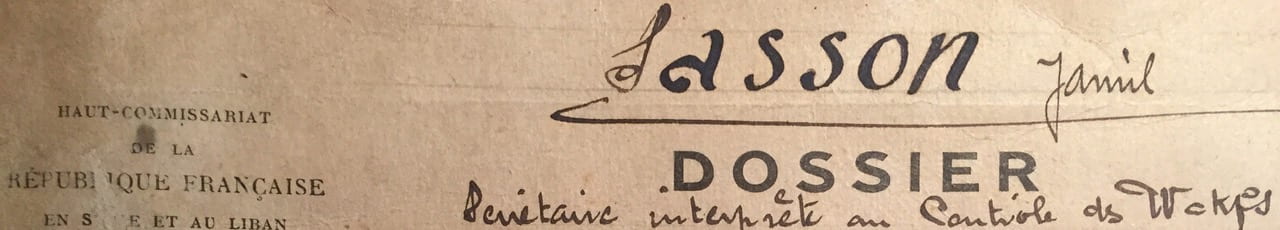

The cover tab on Jamil Sasson’s personnel file. From the Centre des Archives diplomatiques de Nantes.

The French Mandate for Syria and Lebanon (1920-1946) marked the zenith of the French empire in the Middle East but came with novel legal and political constraints. France held the former Ottoman territories that today comprise Lebanon and Syria under the auspices of a League of Nations Class A Mandate trust territory. France was obliged as the Mandatory power (in theory if not always in practice) to safeguard the rights, property, and religious affairs of the people of the trust territory and to answer for their conduct to a Permanent Mandates Commission that sat in Geneva (62-64).

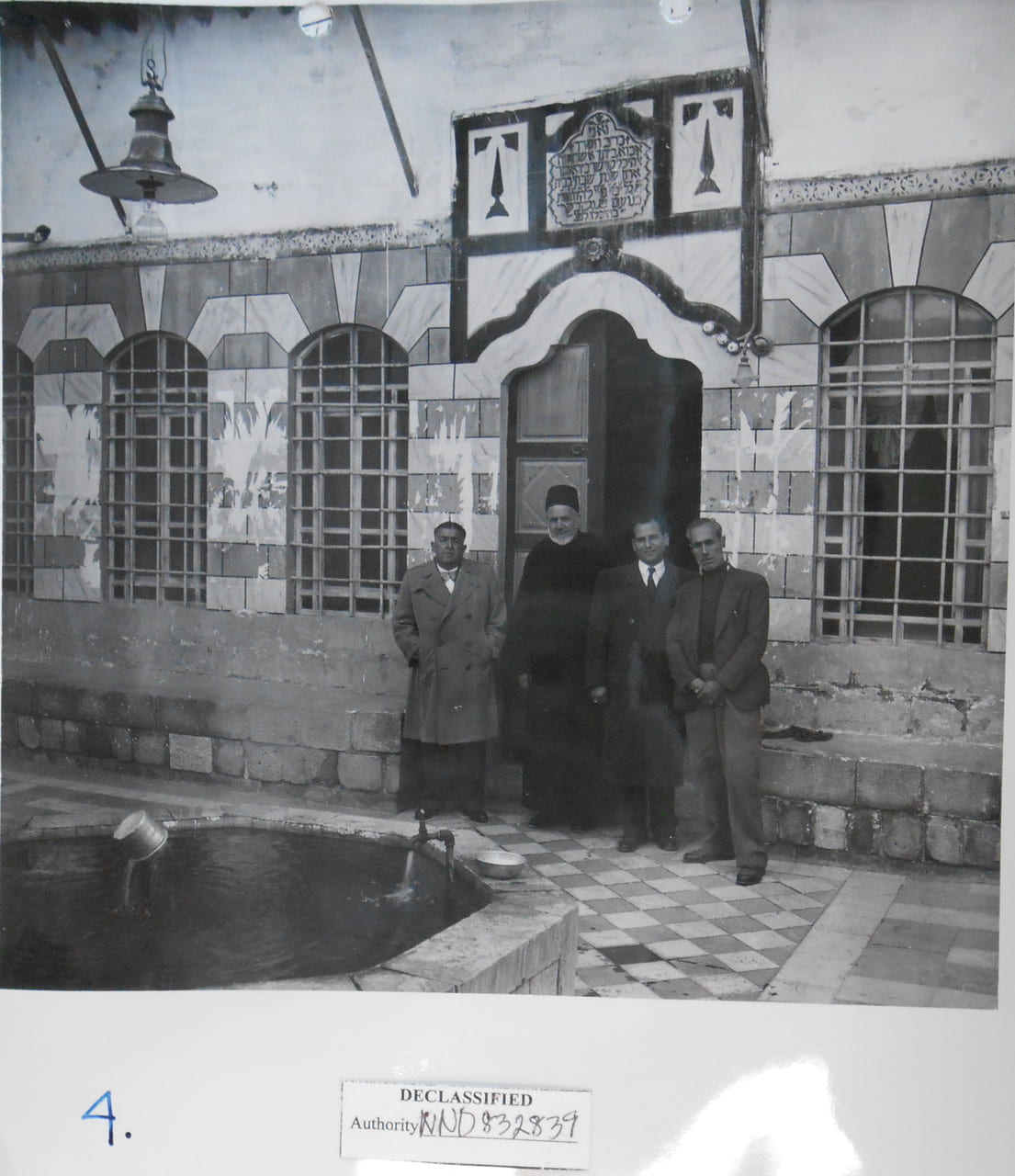

Grand Rabbi of Damascus Hakam Nessm Inudbu at the Synagogue of El Efrange with three companions. (United States National Archives/RG84 Syria Damascus Embassy General Records/1950-1955/510-570.3)

Jamil Sasson was not a French citizen, but the French state that ruled Syria purged him from his profession, rendered him destitute, and sent police to toss his residence in much the same frightening way that French Jews experienced the onset of Vichy. Sasson’s situation underscores how the bureaucratic state can quickly dehumanize and dispossess; what Hannah Arendt called “the banality of evil.” It is also a reminder of the poor practical defense that the idea of equality could offer in the face of bigotry and bureaucratic inertia. Sasson, a Francophone Arab Jew from Damascus, was a trusted interlocutor between the Muslim and Christian religious hierarchies and the French officials in the Contrôle des Wakfs. Personally and professionally, he navigated multiple overlapping and sometimes contradictory worlds. His experience offers granular insights for historians of modern Syria and the French empire. It also should interest scholars concerned with citizenship and those interested in the relationship between individuals and state power. Few individuals in the French Mandate could or did cross the borders – geographic, political, sectarian, linguistic – that Sasson did, let alone with ease or credibility.

Sasson’s personnel records show he was nominally employed as a secrétaire interprète in the Contrôle des Wakfs et de l’Immatriculation foncière; the department charged with overseeing the administration and management of pious endowment property, or waqf. My dissertation research strongly suggests that his duties consisted of espionage and administrative surveillance, rather than clerical work. His French superior Philippe Gennardi, Délégué du Haute-Commissariat auprès du Contrôle Générale des Wakfs, saw Sasson as a lynchpin of a surveillance and intelligence gathering apparatus. This apparatus, controlled by Gennardi, functioned separately from the formal security and intelligence services of the French Mandate. Evidence I assembled from the superficially mundane ephemera of bureaucracy – performance reviews in personal files, receipts submitted for reimbursement, back-and-forth correspondence between different Mandate departments over whose budget should pay Sasson’s salary – indicate that Sasson was an integral figure supporting a sophisticated, semi-autonomous surveillance and human intelligence operation run by Gennardi, focused on waqf (Islamic pious endowments) as a surveillance space. This is a story that is essentially absent from the records of the Service de renseignement, the Mandate’s formal security-intelligence service and from scholarship on the Mandate. Gennardi explicitly described that Sasson’s duties defied his prosaic job title to justify Sasson’s salary in budgetary disputes with his superiors: Sasson was in constant communication with all local administrations and managed the French Mandate’s day-to-day relations with the heads of all of the religious sects in the Mandate. This partnership between French official and Syrian Jewish civil servant was a critical, if understudied element of the formal and informal surveillance capacity of the Mandate state. That is, until the the Fall of France, the installation of Maréchal Pétain in Vichy, and Sasson’s sacking.

On July 20th, 1943 Sasson wrote to his longtime superior Gennardi, with whom he appears to have been close. He had yet been unsuccessful in either returning to his position in the administration or receiving a pension, even after the defeat of the Vichy-aligned administration in the Mandate by Free French and British Commonwealth forces in the summer of 1941. Since first protesting his dismissal at the beginning of 1941, “I have had to abandon all hope of justice given the circumstances and my religion.” Thus Sasson was dispatched by the security machinery of the state, of which he had once surreptitiously been a part.

It is challenging to situate a figure like Sasson in much of the historiography of twentieth century Syria. Notwithstanding more recent scholarship, the Anglo-French historiography of modern Syrian history pivots from elite nationalism under French rule to a series of military coups after independence, and ultimately to the coming of the Baʾth Party. Jamil Sasson’s biography does not fit neatly into this standard narrative. He was born in Damascus in the Ottoman province of Syria, the French Mandate state recorded his nationality as Syrian, and he frequently moved back and forth across the borders of the Mandates for Syria and Lebanon and the British Mandate for Palestine where he had family. He spoke French, worked in the Mandate administration, and was Jewish in his religion. He stood out to senior French administrators in the Mandate and local Christian and Muslim religious chiefs as someone reliable. While his nationality was Syrian, he did not enjoy the protections of citizenship.

Sasson worked for the French Mandate state in a historical context in which Jews (as well as Christians and Muslims) had been intermediaries in commerce and diplomacy during the Ottoman Empire (178-79, see also Michelle Campos, Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-century Palestine, 62-63). Many Jews in the Arab provinces, along with Christians and Muslims, embraced the Ottoman state’s fitful attempts to impose equal citizenship (147). Cast against his sectarian background, Sasson’s personal and professional profile was both complex and quotidian: he played a key role in building the Mandate state, but does not fit the profile of a nationalist hero or a collaborator. Sasson had a government job that was not glamorous on paper, but he performed specialized, sensitive work on issues of religious faith, custodianship and care of pious endowment property, and he carefully built and maintained relationships across sectarian lines, relationships that could be prickly in the best of times. Sasson’s appeal to legal and personal protection in the principle of equality for all speaks to the paradox that defined the interwar period: the vast expansion of rights and international peace-affirming institutions built on the Wilsonian idea of popular sovereignty could not be reconciled with prevailing systems of unequal citizenship, colonialism, and racism. Indeed, formal independence for Syria in 1946 did not resolve this tension, either for national sovereignty or equal citizenship: the postwar United Nations provided better but still unequal international forum and meaningful equal citizenship in independent Syria remained elusive under liberal parliamentary and military regimes alike.

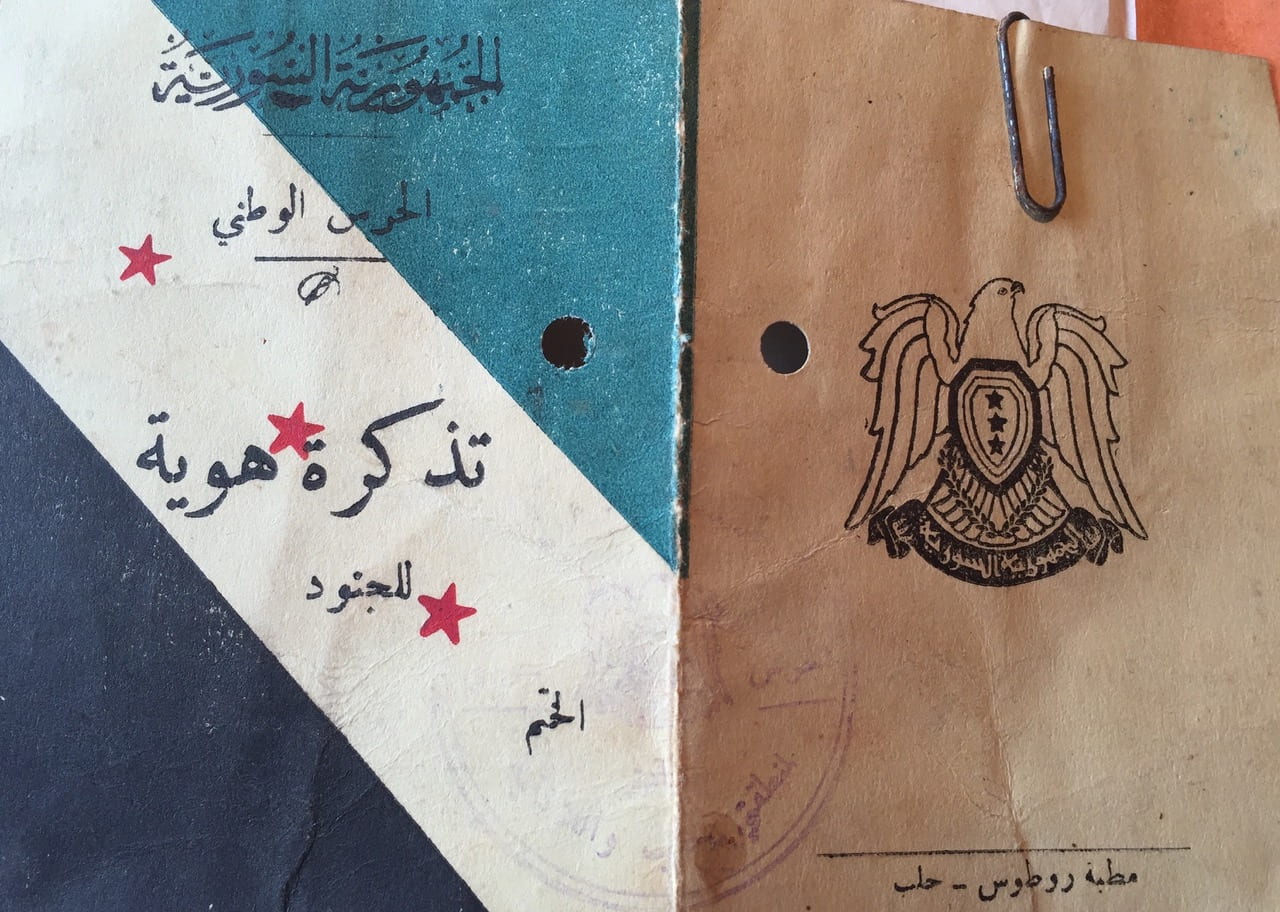

Front and back cover of an identification booklet issued to citizen members of the national guard of the Syrian Republic under French tutelage.

Ideas about “equality for all,” like the institution of responsible French trusteeship of the League of Nations Mandate for Syria seemed to support broad rights, representation, and protection. In practice, they overpromised and underdelivered. The “principle of equality for all” amounted to little practical protection for Sasson by the time he wrote his appeal, yet the idea of equality remained the basis for his case. Equality, as a legal framework, was not sufficiently institutionalized to provide tangible protections. However, equality as an idea persisted.

A number of contemporary tensions reflect the the interwar period that produced the French Mandate in Syria: inadequate yet expanding possibilities of legal personhood and protections for more people; an international system invested with such promise and possibility for peace, but seemingly defined by its inability to prevent conflict; chilling attempts to legally enshrine “extreme vetting” of purported traitors within and enemies without. The discourse of human rights, legal personhood, and citizenship that Sasson invoked in 1941 resonates now with even greater urgency. We would do well to take heed of the experience of a man who found that his world no longer had a place for him.

James Casey is a PhD candidate in the History Department at Princeton University. His dissertation examines the relationship of pious endowment properties to the development of state surveillance capacity in Syria between 1920-1960. He holds an MA in Middle Eastern Studies from The University of Texas at Austin and was a Fulbright Fellow in Syria from 2008-9.

Leave a Reply