By guest contributor Kristin Buhrow

The selection of successors to political and religious leadership roles is determined by different criteria around the world. In the Himalayas, a unique form of determining succession is used: the concept of Tulkuhood. Based in Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism, Himalayan communities, especially in Tibet, operate with the understanding that gifted leaders with a deep and accurate understanding of Buddhist cosmology and philosophy will, after death, return to their communities and continue as leaders in their next life. Upon the death of a spiritual or community leader, his or her assistants and close followers will go in search of the next incarnation—a child born shortly after the previous leader’s death. When satisfied that they have found the new incarnation, the committee of assistants or followers will officially recognize the child, usually under five years old, as a reincarnation, and the child will receive a rigorous education to prepare for their future duties as a community leader. These people are given the title “Tulku.”

This system of succession by reincarnation is occasionally mentioned in Western literature, and is always lent a sense of orientalist mysticism, but it is important to note that in the Tibetan cultural sphere, Tulku succession is the normal, working model of the present day. While Tibetan religious and political leadership structures have undergone great changes in recent years, the system of Tulku succession has been maintained in the religious sector, and for some top political positions was only replaced by democratic election in 2001. Large monasteries or convents in the Himalayas, which often serve as centers of religion, education, and local governance, are commonly associated with a Tulku who guides religious practice and political decision making at the monastery and in the surrounding area. In this way, Tulkus serve a life-long (or multi-life-long) appointment to community leadership.

Like any other modern system of succession, Tulku succession is the subject of much emic literature detailing the definition of Tulkuhood, discussing the powers of a Tulku, and otherwise outlining the concept and process. And, like any other functioning system of succession, some details of the definition of true Tulkuhood are hotly debated. One indication given special attention is that Tulkus go through birth and death under auspicious conditions. These conditions include but are not limited to: occurring on special days of the Tibetan calendar, occurring according to a prophecy that the Tulku himself made previously, unexplainable sweet smells, music issuing from an unknown source, colored lights appearing in the sky, dissolving or disappearance of the mind or body at death, flight, or Buddha images visible upon cremation. While these auspicious conditions of birth or death may go excused or unnoticed, it is thought that all Tulkus are born and die in such circumstances, whether or not the people around them notice. Considering this common understanding, we now turn to one particular Tulku, who makes a controversial and easily politicized assertion: that one of his previous incarnations is that of a miscarried fetus buried beneath his monastery.

***

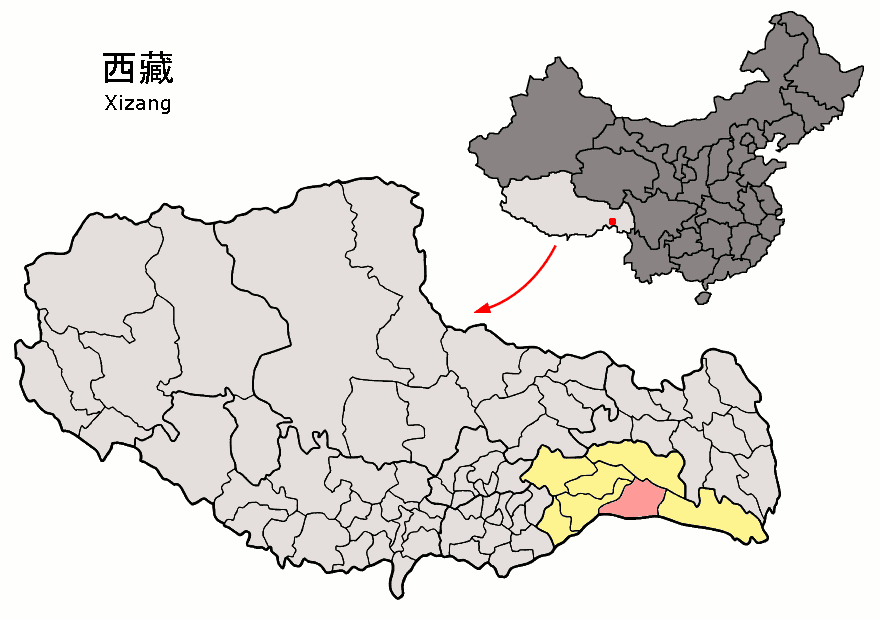

A map showing the Pemako region (now called Mêdog) within Tibet

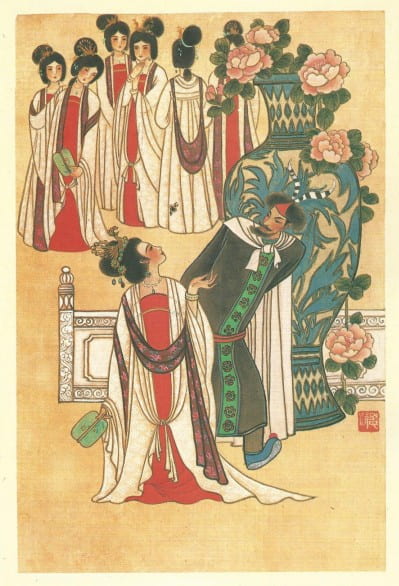

In the mountainous region of Pemako, to the east of Lhasa, there is a small town called Powo. According to Tibetan oral history, it was here, in 641 C.E., that the Chinese Princess Wencheng buried her stillborn child. After being engaged to marry the King of Tibet, Princess Wencheng was escorted from the Tang capital of Chang ‘An (present day Xi’an), to the Tibetan capital, Lhasa, by the illustrious Tibetan minister Gar. Along the way, Princess Wencheng became pregnant with Minister Gar’s child—a union oral history remembers fondly as the result of a loving relationship that had developed over the course of the journey. Some versions of the history assert that Minister Gar intentionally took Wencheng on the longest route to Lhasa so that she could have the baby along the way, but she suffered a miscarriage in Powo. While there was no monastery in Powo at the time, Wencheng, who was an expert Chinese geomancer, recognized the spiritual power of the location. After carefully selecting the gravesite, Wencheng buried her stillborn child, then left to meet her intended in Lhasa.

Aiqing Pan and Zhao Li, “Wencheng and the Tibetan Envoy,” from He Liyi, The Spring of Butterflies and Other Folk Tales of China’s Minority Peoples.

While some sources assert that Princess Wencheng constructed the Bhakha Monastery on top of the grave with her own hands, another origin story exists. Over one thousand years after Wencheng and Minister Gar passed through, a Buddhist teacher who had risen to prominence came to Powo near the time of his death. This teacher was recognized as a reincarnation of the powerful practitioner Dorje Lingpa, who was himself a reincarnation of Vairotsana, a Buddhist intellectual and influential translator. When this teacher came to Powo, he found the same spot where Wencheng had buried her baby, and he planted his walking stick in the ground, which miraculously grew into a pine tree. It was then that the Bhakha Monastery was built in the same vicinity. Regardless of the accuracy of these oral histories, it is clear that the presence of the infant grave was a known factor when the monastery was named, as Bhakha (རྦ་ཁ་ or སྦ་ཁ་) means “burial place”. The teacher whose walking stick demonstrated the miracle became known as the first Bhakha Tulku. We are now, as of 2017, in the time of the tenth Bhakha Tulku, who still has influence over the same monastery, as well as related monasteries in Bhutan and the United States.

The Tenth Bhakha Tulku (photo credit: Shambhala Center of New York)

In addition to the list of renowned former lives mentioned previously, the Bhakha Tulku has also claimed Wencheng and Minister Gar’s child as one of his past lives. While this claim to such a short and seemingly inauspicious life is unusual for a Tulku, it is not an impossibility according to the standards of Tulkuhood in the Nyingma sect, to which the Bhakha Tulku belongs. In the Nyingma tradition, and all other Vajrayana sects, life is considered to begin at conception. By this principle, a stillborn fetus constitutes a life, making it possible that that life could have been part of a Tulku lineage. According to a description by Tulku Thondup, a translator and researcher for the Buddhayana Foundation and contemporary Tulku associated with the Dodrupchen Monastery, in Incarnation: The History and Mysticism of the Tulku Tradition of Tibet, the primary role of a “Birth Manifested Body Tulku” is “to serve others […] in any form that leads a being or beings toward happiness, peace, and enlightenment, either directly or indirectly” (13). With this perception of Tulku leadership, the controversy surrounding the idea that a life culminating in miscarriage could be worthy of the title of Tulku is easily understood.

Some individuals participating in this debate assert that a miscarried fetus could not fulfill the requirement of compassionate servitude. Cameron David Warner goes so far as to argue that the emotional pain that miscarriage necessarily brings to the mother renders the life of that child devoid of any positive outcome—its only effect being a mother’s grief. However, one key idea posited by Tulku Thondup is that a Tulku’s life can help the spread of Buddhism and compassion, not only directly, but also indirectly. When viewed in the context of history, it is possible that the death of this child, for this life to go no further, was a course of events that allowed Buddhism to spread further into Tibet.

At the time of Wencheng’s arrival in Tibet, Buddhism was fairly uncommon in the area, the most common religion being a form of animistic shamanism called Bon. Both Tibetan and Chinese historiography cite Wencheng among the first foreigners to bring Buddhist artifacts into Tibet (see Blondeau and Buffetrille, Slobodnik, Kapstein). It is possible that if Wencheng were to arrive in Lhasa with a child that the Tibetan king, Songstan Gampo, would have reacted negatively, potentially harming Wencheng herself or the larger relationship between the Tibetan Empire and Tang China. While this is merely conjecture, it does present an argument in which a Tulku could have demonstrated compassionate servitude in this unusual form.

Interestingly, while the Bhakha Tulku’s claimed past life has inspired controversy, this particular assertion is not mentioned in official profiles or other monastic materials. This decision to avoid such a sensitive topic in public texts could be an attempt to smooth over controversy within the religious community (where the debate continues). Alternatively, this choice could be motivated by a desire to avoid politicization by Chinese government officials, who have been altering the historical narrative surrounding Wencheng’s life in Tibet to model a positive relationship between the generous paternal state of China and Tibet, its vassal. While the Bhakha Tulku currently devotes his energies to other issues, this unusual past life serves not only to symbolically connect China and Tibet, but also challenges the traditional notion of what it means to be a benevolent public servant.

Kristin Buhrow is a graduate student at the University of Oxford pursuing a Master’s degree in Tibetan & Himalayan Studies.

Leave a Reply