by guest contributor Steven McClellan

The historian Fritz K. Ringer claimed that for one to see the potency of ideas from great thinkers and to properly situate their importance in their particular social and intellectual milieu, the historian had to also read the minor characters, those second and third tier intellectuals, who were barometers and even, at times, agents of historical change nonetheless. One such individual who I have frequently encountered in the course of researching my dissertation, was the economist Ludwig Bernhard. As I learned more about him, the ways in which Bernhard formulated a composite of positions on pressing topics then and today struck me: the mobilization of mass media and public opinion, the role of experts in society, the boundaries of science, academic freedom, free speech, the concentration of wealth and power and the loss of faith in traditional party politics. How did they come together in his work?

Ludwig Bernhard (1875-1935; Bundesarchiv, Koblenz Nl 3 [Leo Wegener], Nr. 8)

Part of Bernhard’s early academic interest focused on the Polish question, particularly the “conflict of nationalities” and Poles living in Prussia. Unlike many other contemporary scholars and commentators of the Polish question, including Max Weber, Bernhard knew the Polish language. In 1904 he was appointed to the newly founded Königliche Akademie in Posen (Poznań). In the year of Althoff’s death (1908), the newly appointed Kultusminister Ludwig Holle created a new professorship at the University of Berlin at the behest of regional administrators from Posen and appointed Bernhard to it. However, Bernhard’s placement in Berlin was done without the traditional consultation of the university’s faculty (Berufungsverfahren).

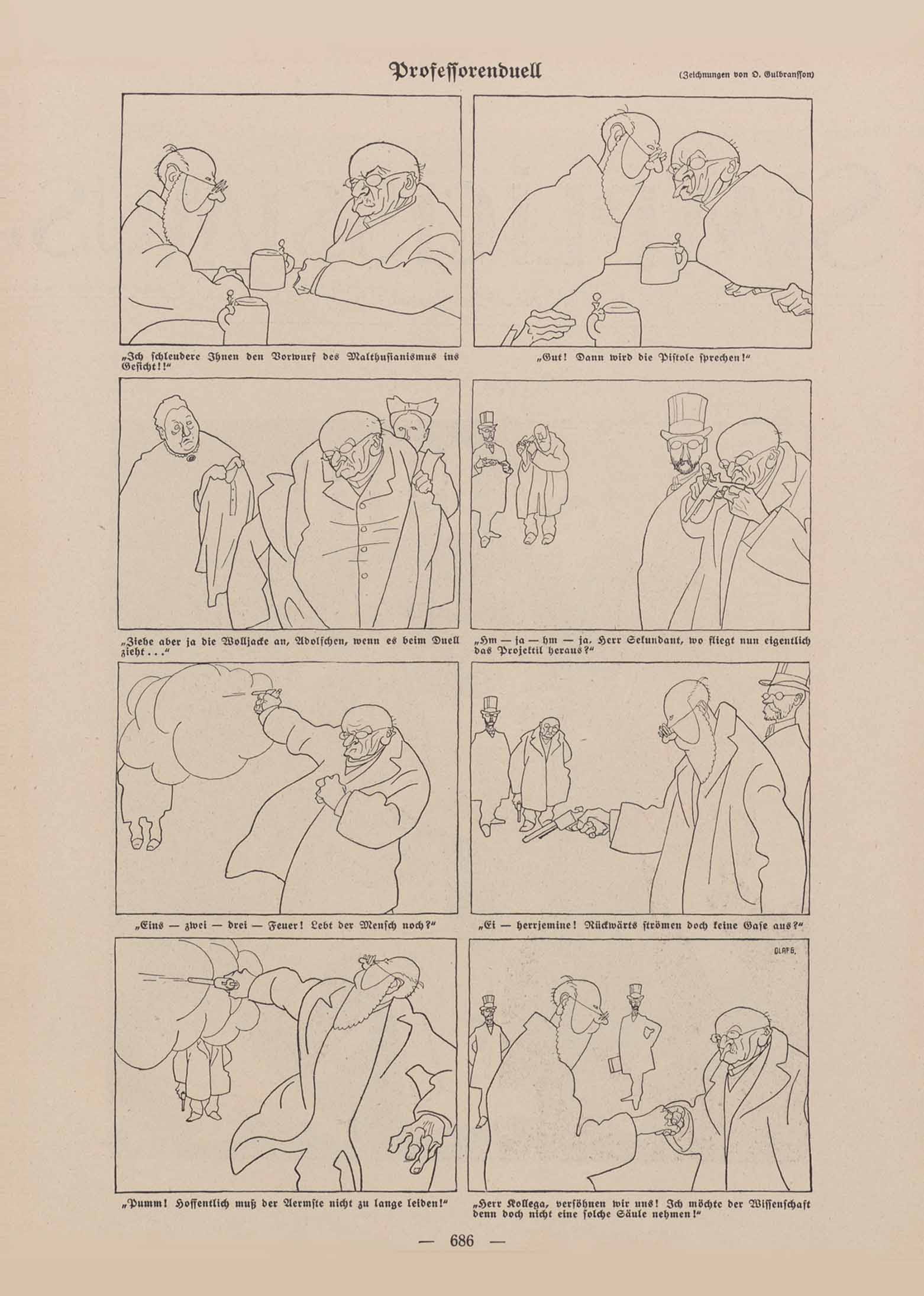

The Berliner Professorenstreit of 1908-1911 ensued with Bernhard’s would-be colleagues, Adolph Wagner, Max Sering and Schmoller protesting his appointment. It escalated to the point that Bernhard challenged Sering to a duel over the course lecture schedule for 1910/1911, the former claiming that his ability to lecture freely had been restricted. The affair received widespread coverage in the press, including attracting commentaries from notables, such as Max Weber. At one point, just before the affair seemed about to conclude, Bernhard published an anonymous letter in support of his own case, which was later revealed that he was in fact the author. This further poisoned the well with his colleagues. The Prussian Abgeordnetenhaus (Chamber of Deputies) would debate the topic: the conservatives supported Bernhard and the liberal parties defended the position of the Philosophical Faculty. Ultimately, Bernhard would keep his Berlin post.

The affair partly touched upon the threat of the political power and the freedom of the Prussian universities to govern themselves—a topic that Bernhard himself extensively addressed in the coming years. It also concerned the rise of the new discipline of “business economics” gaining a beachhead at German secondary institutions. Finally, the Professorenstreit focused on Bernhard himself, an opponent of much of what Schmoller and his colleagues in the Verein für Socialpolitik stood for. He proved pro-business and an advocate of the entrepreneur. Bernhard also showed himself a social Darwinist, deploying biological and psychological language, such as in his analysis of the German pension system in 1912. He decried what he termed believed the “dreaded bureaucratization of social politics.” Bureaucracy in the form of Bismarck’s social insurance program, Bernhard argued, diminished the individual and blocked innovation, allowing the workers to become dependent on the state. Men like Schmoller, though critical at times of the current state of Prussian bureaucracy, still believed in its potential as an enlightened steward that stood above party-interests and acted for the general good.

Bernhard could never accept this view. Neither could a man who became Bernhard’s close associate, the former director at Friedrich Krupp AG, Alfred Hugenberg. Hugenberg was himself a former doctoral student of another key member of the Verein für Socialpolitik , Georg Friedrich Knapp. Bernhard was proud to be a part of Hugenberg’s circle, as he saw them as men of action and practice. In his short study of the circle, he praised their mutual friend Leo Wegener for not being a Fachmann or expert. Like Bernhard, Hugenberg disliked Germany’s social policy, the welfare state, democracy, and—most importantly—socialism. Hugenberg concluded that rather than appeal directly to policy makers and state bureaucrats through academic research and debate, as Schmoller’s Verein für Socialpolitik had done, greater opportunities lay in the ability to mobilize public opinion through propaganda and the control of mass media. The ‘Hugenberg-Konzern’ would buy up controlling interests in newspapers, press agencies, advertising firms and film studios (including the famed Universum Film AG, or UfA).

In 1928, to combat the “hate” and “lies” of the “democratic press” (Wegener), Bernhard penned a pamphlet meant to set the record straight on the Hugenberg-Konzern. He presented Hugenberg as a dutiful, stern overlord who cared deeply for his nation and did not simply grow rich off it. Indeed, the Hugenberg-Konzern marked the modern equivalent to the famous Raiffeisen-Genossenschaften (cooperatives) for Bernhard, providing opportunities for investment and national renewal. Furthermore, Bernhard claimed the Hugenberg-Konzern had saved German public opinion from the clutches of Jewish publishing houses like Mosse and Ullstein.

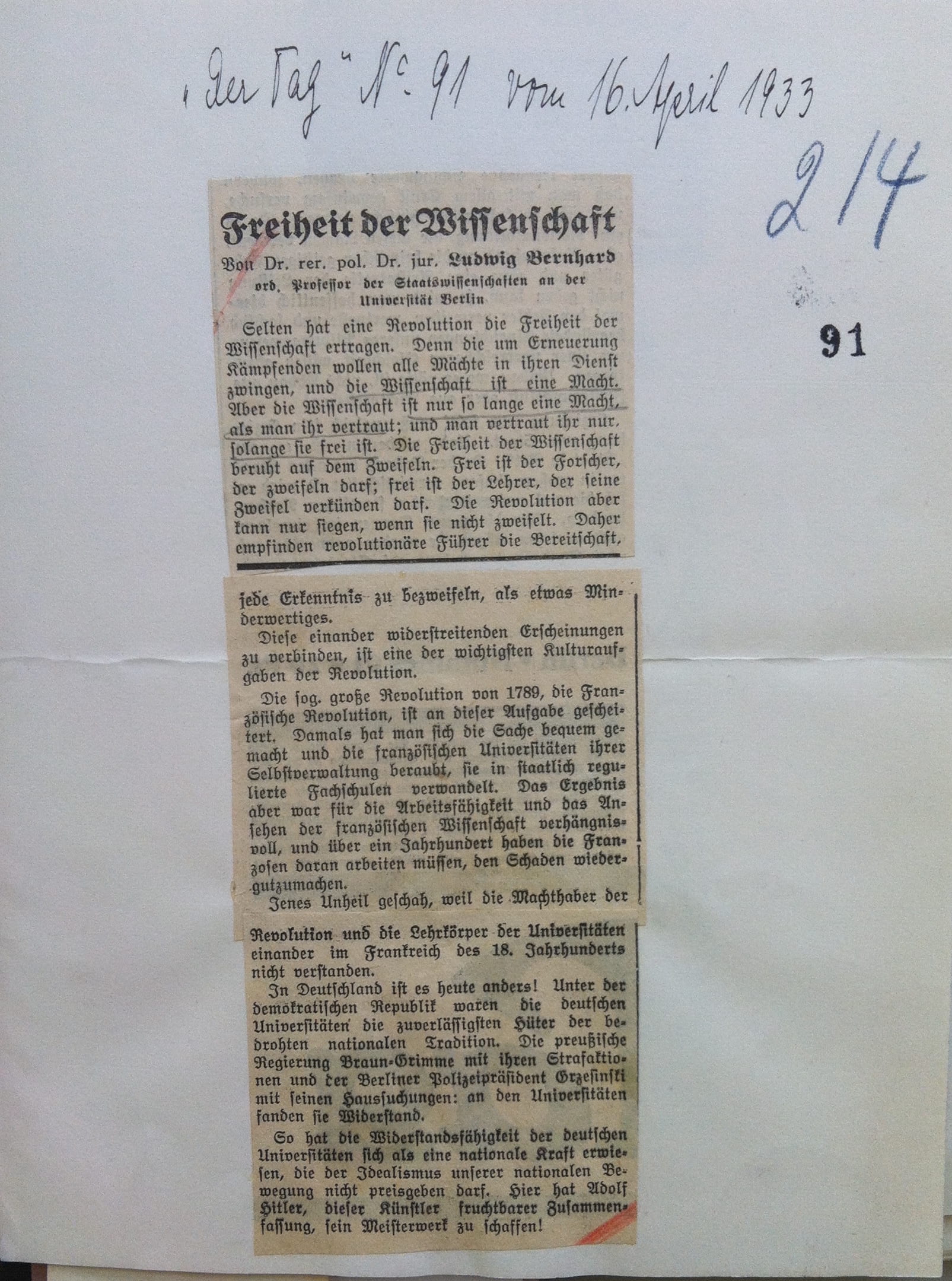

Both Bernhard and Hugenberg pushed the “stab-in-the-back” myth as the reason for Germany’s defeat in the First World War. The two also shared a strong belief in fierce individualism and nationalism tinged with authoritarian tendencies. These views all coalesced in their advocacy of the increasing need of an economic dictator to take hold of the reins of the German economy during the tumultuous years of the late Weimar Republic. Bernhard penned studies of Mussolini and fascism. “While an absolute dictatorship is the negation of democracy,” he writes, “a limited, constitutional dictatorship, especially economic dictatorship is an organ of democracy.” (Ludwig Bernhard: Der Diktator und die Wirtschaft. Zurich: 1930, pg. 10).

Hugenberg came to see himself as the man to be that economic dictator. In a similar critique mounted by Carl Schmitt, Bernhard argued that the parliamentary system had failed Germany. Not only could anything decisive be completed, but the fact that there existed interest-driven parties whose existence was to merely antagonize the other parties, stifle action and even throw a wrench in the parliamentary system itself, there could be nothing but political disunion. For Bernhard, the socialists and communists were the clear violators here.

Ludwig Bernhard, »Freiheit der Wissenschaft« (Der Tag, April 1933; BA Koblenz, Nl 3 [Leo Wegener)], Nr. 8, blatt 91; click for larger image)

Ludwig Bernhard died in 1935 and therefore never saw Hitler’s completed picture of a ruined Germany. An economic nationalist, individualist, and advocate of authoritarian solutions, who both rebelled against experts and defended the freedom of science, Bernhard remains a telling example of how personal history, institutional contexts and the perception of a heightened sense of cultural and political crisis can collude together in dangerous ways, not least at the second-tier of intellectual and institutional life.

Steven McClellan is a PhD Candidate in History at the University of Toronto. He is currently writing his dissertation, a history of the rise and fall, then rebirth of the Verein für Sozialpolitik between 1872 and 1955.

1 Pingback