Here are some of the books that the Blog’s editors have lined up for summer. From art history to critical theory, from fiction to poetry, we’ve got you covered if you’re looking for something to pick up during the academic off season.

Erin

I have a confession to make: I have never read D.F. McKenzie’s Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts from cover to cover. As a working bibliographer I encounter a huge variety of “texts,” from incunabula to 20th century manuscripts printed on Xerox machines, to 45 rpm sound recordings, even recordings on magnetic tape. As Jerome McGann wrote in a 1988 review for the London Review of Books, “In a series of trenchant illustrations, [McKenzie] unfolds a profound truth about ‘the book’ itself – and thence about every kind of possible text: that it is meaning-constitutive not simply in its ‘contained’ or delivered message, but in every dimension of its material existence.” So, Marshall McLuhan meets Phillip Gaskell and Fredson Bowers? I’m about to find out.

Eve Babitz, age 14, reading a biography of novelist and screenwriter Elinor Glyn.

I’m also going for it with Hollywood fiction to support my work with a private collection of film scripts and cinematic ephemera this summer. As a New Yorker, Los Angeles seems the land of good vibes, great hair, and Fridays off to me – I loved Pynchon’s Inherent Vice and P.T. Anderson’s film adaptation. So, I’m looking for a sense of the place on the ground, without completely bursting my Beach Boys bubble. I just started Eve Babitz’s Eve’s Hollywood, up next is Darcy O’Brien’s A Way of Life Like Any Other, and then comes Don Carpenter’s Hollywood Trilogy. Babitz is a sophisticated, well read, well connected, and totally liberated mid-century California woman, and best of all she is a tremendous writer. O’Brien and Carpenter’s books both come highly recommended as novels of the note-so-glamorous side of Hollywood life on both ends of the 20th century.

Spencer

The Thackery T. Lambshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric & Discredited Diseases, ed. Jeff VanderMeer and Mark Roberts (2003): I’m a hopeless science fiction/fantasy addict, as well as a history of science buff. Rarely do those passions come together, but some of the genre’s cleverest writers—Neil Gaiman, Michael Moorcock, Alan Moore—have compiled this darkly comic “anthology” of imaginary maladies. Being something of a hypochondriac, I am a little nervous (in a good way).

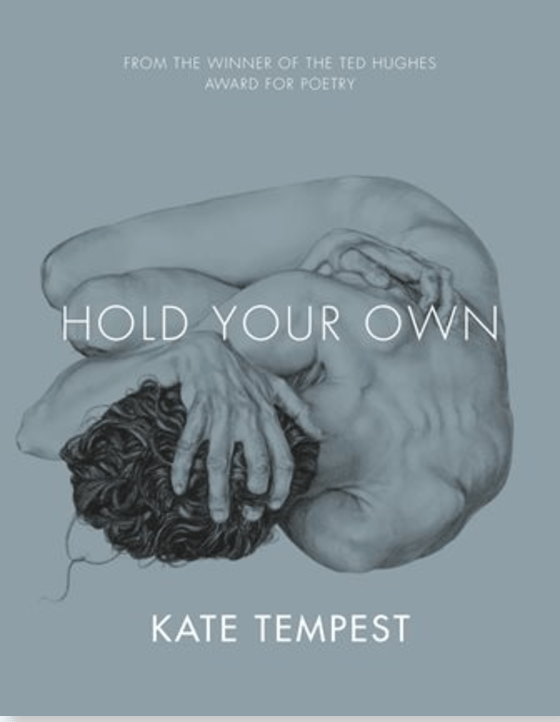

Kate Tempest, Hold Your Own (2014). Kate Tempest is a brilliant, prize-winning poet from the UK, whose debut collection, Hold Your Own, explores gender, sexuality, and the life cycle through a reimagining of the story of Tiresias, the blind prophet of Greek mythology. A brief sample: “Snakes. Two snakes! / Coiling, uncoiling / Boiling and cooling / Oil in a cauldron / Foil in a river / Soil on a mood ring.”

Kate Tempest, Hold Your Own (2014). Kate Tempest is a brilliant, prize-winning poet from the UK, whose debut collection, Hold Your Own, explores gender, sexuality, and the life cycle through a reimagining of the story of Tiresias, the blind prophet of Greek mythology. A brief sample: “Snakes. Two snakes! / Coiling, uncoiling / Boiling and cooling / Oil in a cauldron / Foil in a river / Soil on a mood ring.”Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe (1719). The beach read extraordinaire. One of those books that has sat on my shelf unread for far too long. Arguably the first English novel. It created its own genre—the Robinsonade—of castaway or “desert island” stories.

Cynthia

One summer, I carried W.G. Sebald’s After Nature all over Europe, like a talisman. I read it quietly in hotel rooms, and over coffees in little squares. The historian’s work can be alienating, so much solitude, so many hours and days spent unmoored from your own time. Here was someone else who did that deep dive, and came back with a work of lapidary beauty. It’s a work that always sets me thinking about the writer’s craft.

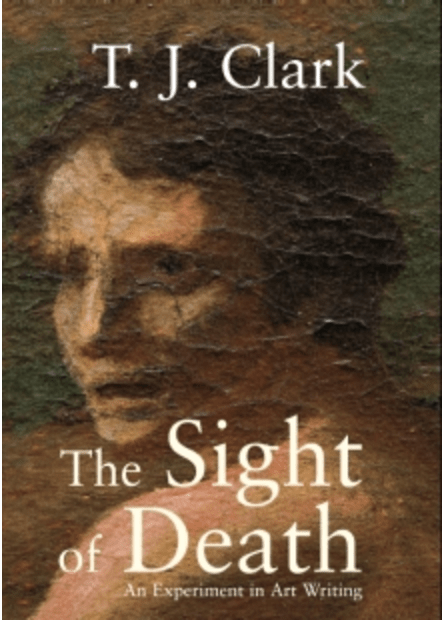

Summer, for me, is also a time for re-reading those books that first opened certainintellectual doors. I often go back to T.J. Clark’s work – whether the more conventional art historical works, like The Painting of Modern Life – or stranger ones like Farewell to an Idea, The Sight of Death. Clark both knows how to look and how to leap from ekphrasis to argumentation. I plan to read and and look at the art work under discussion again, and somewhere between reading and looking, come to a new understanding of work and text.

But it’s also a season of sun, and salt, and blue. This summer, I’ll have Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse in my beach bag, for something that feels deceptively diaphanous, along with Joan Didion’s South and West for a glimpse at another writer’s working process. I’m also carrying Solmaz Sharif’s first book of poetry, Look, because something about the heat and pain in these poems demands slow, careful reading. Read a stanza. Look at the sea. Repeat. If I should find myself stuck at an airport, I’ll reach for Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet. I second Eric on this recommendation. They are gripping. They pull you into another world and nothing makes a four-hour travel delay go by faster.

Eric

Elena Ferrante. The Neapolitan Quartet surely need me least of all to sing their praises at this point. They are very good and (at least for me) gripping enough that the summer is the right time to sit down with them. Pay more attention to the backdrop of postwar Italy than to the sexist shenanigans around authorship that have recently overshadowed the novels themselves.

Moishe Postone, Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory (Cambridge, 1993). This classic in recent critical theory has since provided an important base for significant work in intellectual history. I should have read it a long time ago.

Benjamin Straumann, Crisis and Constitutionalism: Roman Political Thought from the Fall of the Republic to the Age of Revolution (Oxford, 2016). This is well outside my area of expertise, but I just finished teaching a semester of Roman history and David Armitage’s Civil Wars whetted my appetite for this sort of thing.

Derek

A film series and book pairing: the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive presents a summer-long series on the centennial of Jean-Pierre Melville (1917-1973). His oeuvre extends well beyond films about the Occupation of France, but I’ll look at those films through the lens of this book, by Professor Leah Hewitt, Remembering the Occupation in French Film: National Identity in Postwar Europe (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

Jean-Pierre Melville

Mary Sarah Bilder’s Madison’s Hand Revising the Constitutional Convention (Harvard UP, 2015), through a range of fascinating research tools, invites us into James Madison’s writing of his Notes on the Constitutional Convention of 1787, showing the complex biography of a text often treated as an unimpeachable primary source.

Another pairing—and in this vein of the biography of a text: William Carlos Williams’s epic American poem Paterson (1946-1958) and the multiply eponymous film Paterson (2016), a film about writing poems, which has stirred interest in Williams’s work.

Disha

I have read the historical novel Hild by Nicola Griffith every summer since 2014. Griffith is best known for her fantasy writing, and has produced a stirring and lush story with fantastical elements that is rooted in the fragmentary records left by Bede of the life of St. Hilda of Whitby. Griffith also kept a blog in which she recorded the progress of her historical writing: https://gemaecce.com/. Set in 7th century Anglo-Saxon England, this novel details the childhood and early adulthood of a young woman of a royal house, and moves languidly through loss, sexuality, the rhythms of political and everyday life, and the tumult of living in changing and unprecedented times. I find it equally comforting and unsettling. A sequel is forthcoming. The author’s interview in The Paris Review is also a helpful look at what writing about the fantastical/real is like.

Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital by Vivek Chibber is a book I have read about, but have not read. I hope to correct that this summer. It is a work with immense political stakes as well as implications for work done in the space between the fields of intellectual history, critical theory, postcolonial studies, political thought, and global history (a zone with which I find myself increasingly preoccupied). I will no doubt have to read it alongside the many critiques and responses to it (some of which has been helpfully collected here).

Daniel Brückenhaus’s 2017 book, Policing Transnational Protest: Liberal Imperialism and the Surveillance of Anticolonialists in Europe: 1905-1945 is an exploration of the effect of state pressure, surveillance, and policing on anti-imperial activity. Brückenhaus has detailed here the development of a transnational anti-colonial government in the first half of the twentieth century, in northwestern Europe in particular. This book is also framed in terms of a pre-history of current debates about such a transnational surveillance operation, and the trajectory of such an entity over the last century told through archival research in Britain, France, and Germany.

Basma

Richard Swedberg Tocqueville’s Political Economy (2009). Tocqueville: political thinker, proto-sociologist, or political economist? Although the text primarily interests me for its perspective on Tocqueville in America, it is sure to prove useful to intellectual historians more generally as well. By examining the intersection between Tocqueville’s thought as a proto-sociologist and political thinker, Swedberg unearths an easily missed yet crucial aspect of Tocqueville’s outlook and method: political economy.

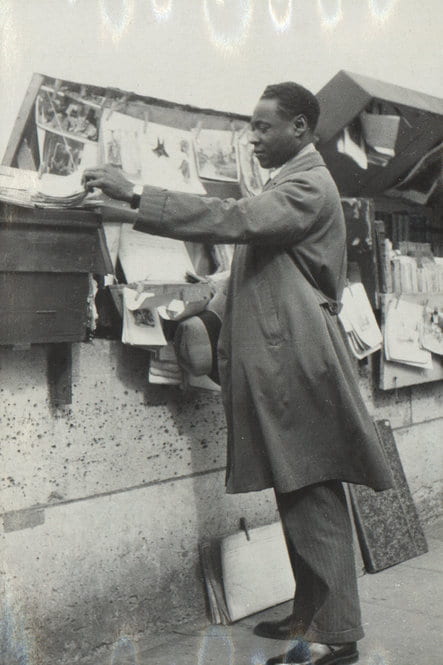

Photograph of Claude McKay, taken for ‘Home to Harlem’ promotion, c. 1928.

David Motadel Islam and Nazi Germany’s War (2014). In good graduate student fashion, this is one of the books I preordered, received a few months later, read the first chapter meticulously, and promptly placed on my bookshelf. Summer is finally here and with it more time for pleasure reading. This text is fascinating for its depiction of colonial societies’ interaction with Nazi Germany and the latter’s views on Islam.

Claude Mckay Amiable with Big Teeth (2017). I first encountered Claude McKay after reading Brent Edwards’ “Taste of The Archive.” Written in 1941, a Columbia graduate student discovered the unpublished manuscript in 2012 (an amusing story in its own right). The novel touches on the mood and climate in Harlem on the cusp of World War II.

1 Pingback