by guest contributor Adam Fales

Who, in short, authored Congreve? Whose concept of reader do these forms of the text imply: the author’s, the actor’s, the printer’s, or the publisher’s? And what of the reader?

D. F. McKenzie, Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts (1986)

When Herman Melville died in 1891, he was hardly the literary giant we read today. He spent the end of his life working as a customs inspector and writing poetry that few read. His unacknowledged death made his posthumous recovery more dramatic, when literary critics like Raymond Weaver, Carl Van Doren, and Lewis Mumford brought him back to scholarly attention thirty years later, in what we now call the “Melville Revival.” However, recent scholars like Kathleen Kier, Elizabeth Renker, and Jordan Stein have shown how the dominant narrative of Melville’s singular “Revival” erases the contributions of homosexuals and women to Melville’s legacy. These debates reconsider what and whose labor scholars acknowledge in the historical narratives they tell.

Bibliography—the study of books as material and cultural objects—is the approach most attuned to this labor. Philip Gaskell’s A New Introduction to Bibliography (1972) shows how scholarly interpretation of a text relies on an understanding of the conditions in which it was produced. Through bibliography, Gaskell and his student D. F. McKenzie show the need to understand texts as a series of material changes, which are subsequently reabsorbed and reinterpreted by readers whose relationship to the printed word changes over time. McKenzie’s approach to bibliography also attends to the multiplicity of actors that intersect in the production and circulation of any given text. Whereas these analyses often focus on the printing-house, bibliography also complicates the way scholars understand the creation, copying, and correction of a manuscript. Following McKenzie, I use the case of Herman Melville to reconsider how we segregate the labor of “authors, actors, printers, and publishers.” Bibliography’s perspective shows that these various agents are actually collaborators, whose contributions make up the printed text, as we know it. If we ask, “who, in short, authored” Herman Melville, we must look beyond Melville himself for the answer.

Divisions of bibliographic labor imprinted themselves on the life of Herman’s wife, Elizabeth Shaw Melville. She describes his literary production in a May 5, 1848 letter to her stepmother:

I should write you a longer letter but I am very busy today copying and cannot spare the time so you must excuse it and all mistakes. I tore my sheet in two by mistake thinking it was my copying (for we only write on one side of the page) and if there is no punctuation marks you must make them yourself for when I copy I do not punctuate at all but leave it for a final revision for Herman. I have got so used to write without I cannot always think of it. (quoted in Renker, 139-40)

Elizabeth Shaw Melville: copyist, editor, and wife of Herman Melville. Wikimedia Commons.

Written while she copied her husband’s manuscript for his third novel Mardi, this letter documents not just Elizabeth’s unacknowledged labor but also how that labor impacted her life. Herman’s practice of having Elizabeth copy without punctuation affects her writing style, as she proceeds through long, winding, unpunctuated sentences. For many Melville scholars, this letter illuminates Herman’s writing process, but it also illustrates Elizabeth’s own intimate involvement in the production of these texts. She was Melville’s closest reader, deciphering his messy script, clarifying his corrections, and making the other changes necessary for his work to be consumed, first by a printer, and then by a reading public. Her letter notes that the text underwent a “final revision” by Herman, but Elizabeth’s labor frames scholarly understanding not just of Melville’s textual history but of much of his life’s work as well.

Elizabeth was the first Melvillean. Beyond copying Herman’s work in his life, she maintained his literary reputation after his death. Her labor exhibited itself in the subtlest ways. On the back flyleaf of the Melville family’s copy of The Piazza Tales, someone (likely Elizabeth) wrote the original publication dates of all the stories collected in the book. This book by Herman, annotated by Elizabeth, illustrates the intertwined nature of their shared bibliographic production, and the importance of this shared labor in the reception and study of Herman Melville. This book shows how Elizabeth’s labor exists in a tradition of note-taking and information management that bibliographic scholars like Ann Blair and Richard Yeo recognize as intellectual work in its own right. Considered within these histories, Elizabeth’s labor is a cumulative practice, in which textual copying establishes an expertise that she draws from to edit later editions of those texts. While Elizabeth had no monographs, scholarly editions, or novels of her own, her labor made those that would come after her possible.

Kathleen Kier shows how Elizabeth made deals, prepared texts, and supplied biographical information for the posthumous editions of Herman’s early novels Typee and Omoo that Arthur Stedman would publish. Even though scholars like Merton Sealts give Stedman the majority of the credit for this initial revival, Kier calls attention to correspondence that illustrates the financial and editorial support that Elizabeth put into this project, which ultimately failed due to a lack of reciprocal support from Stedman. Drawing from her invaluable knowledge as Herman’s copyist, Elizabeth edited the text of Typee, “so that the United States Book Company’s edition might better be called Stedman’s and hers” (Kier 76). Kier notes that this edition was Melville’s most widely read work prior to his scholarly revival, but Elizabeth’s role in its creation went largely underappreciated until much later.

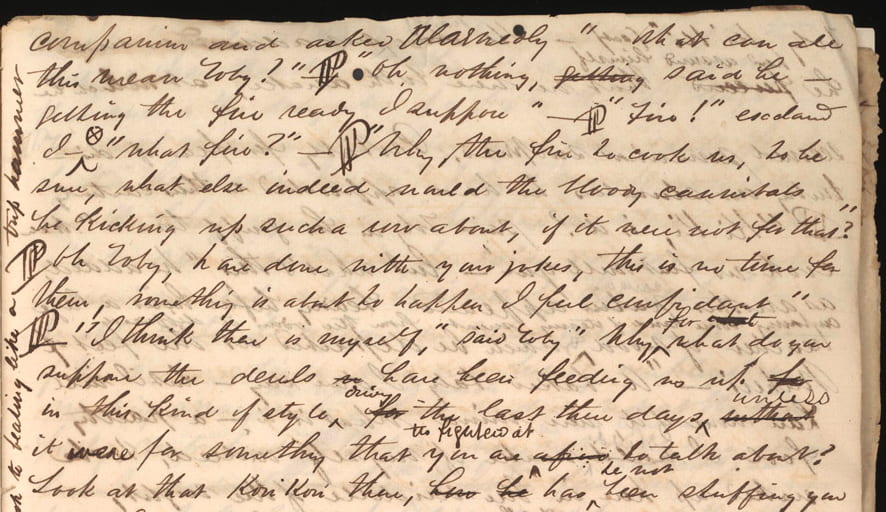

Part of a manuscript page for Typee. Credit: Digital Humanities Quarterly.

Scholars have largely misconstrued Elizabeth’s role in Herman’s life and work. Following the work of Merton Sealts’s Melville’s Reading (1948-50), Wilson Walker Cowen sought to transcribe every known instance of marginal notes in books owned and borrowed by Melville for his Harvard dissertation Melville’s Marginalia (1965). Contributing to the ongoing recreation of an archive of Herman’s life and work, Cowen’s scholarship resembled Elizabeth’s information management. Rather than recognize their shared project, Cowen came into conflict with Elizabeth, when he encountered some erased marginal notes. Concluding that “[p]ersonal feelings and reactions to women make up the balance of the erased material,” he leverages this “balance” to conclude that one of Herman’s female relatives was the culprit (xix). He blames Elizabeth. In this way, Cowen notes Elizabeth’s destructive force in the Melvillean archive, but he hardly acknowledges her productive contributions. For example, Elizabeth Renker considers how Elizabeth protected Herman’s posthumous reputation through erasing this same marginalia. Considered this way, erasure was an act of preservation.

Herman’s reputation was rebuilt after his death, whether through Elizabeth’s “revival that failed” or the later, scholarly revival that receives credit. This posthumous scholarship frames how authors like Herman Melville are approached, studied, and discussed. Renker and Kier not only recover Elizabeth’s forgotten role but also reclaim that role’s positive contribution, as they reconsider the role of labor in literary history. Their approach aligns with the insights of bibliography, in a similar manner to Barbara Heritage’s recent work. Heritage shows how bibliography enhances literary analysis “with a focus on the actual, historical copies of books being read,” but bibliography also reveals the invisible labor that produces those “actual, historical” books. Elizabeth’s labor not only preserved her husband’s legacy in print but also provides the material basis for Melville studies. The scholars we consider responsible for the “Melville Revival” depended upon Elizabeth’s lifelong efforts to organize, edit, and transcribe her husband’s life and writing. As the unacknowledged precursor to mid-century Melville scholars, she not only did the same work of copying and information management that made the careers of Sealts and Cowen (the first experts on Herman’s handwriting, after Elizabeth), but she also made the editions from which Weaver, Van Doren, and Mumford would draw in their initial revival of Herman Melville.

It’s hardly a coincidence that the figures erased from literary history resemble those that have also been excluded from the academy (this account elides the people of color traditionally excluded as well). Bibliography shows the contribution of everyone involved in the production, circulation, and reception of texts, recovering those erased from traditional scholarly narratives. Elizabeth’s fate resonates with the recent #ThanksForTyping, which notes the unnamed women “thanked” in acknowledgements sections for typing their husbands’ manuscripts (but whose work, like Elizabeth’s, often went beyond mere copying). Cowen thanks his unnamed wife, who “helped with everything” (iv). But when his dissertation was revived and revised as the ongoing Melville’s Marginalia Online, the staff page lists sixty-seven names. Elizabeth is just one figure we can recover, in the ongoing transformation of academic practices fomented by the Digital Humanities. An approach from bibliography hardly provides clear-cut divisions between author and scrivener; it messes up neat narratives of singular American authors recovered by mid-century scholars. However, bibliography calls attention to the labor that produces these texts. If the answers from that perspective are not straightforward, they might instead be more just.

Elizabeth left Herman’s manuscript without punctuation. Perhaps, then, our labor begins where we fill in the question marks.

Adam Fales grew up in Kansas and graduated from Fordham University. He is currently a digital scholarship intern as well as a manager at Book Culture in New York City. You can find him on Twitter @SupplyanddeMan. He typed this article himself, but couldn’t have done so without the support of friends, instructors, and his editor Erin McGuirl at JHIBlog.

2 Pingbacks