By Editor Spencer J. Weinreich

Pulp is one of the great unheralded archives of American cultural history. Ephemeral by its very nature, the pulp magazine or paperback brought millions of readers the derring-do of detectives and superheroes, the misadventures of doomed lovers, and the horrors of gruesome monsters. They were the birthplaces of Tarzan and Zorro, and published the work of such luminaries as Agatha Christie, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Mark Twain, and Tennessee Williams.

The cover of the May-June-July 1924 issue of Weird Tales

In 1924, readers of the fantasy and horror pulp Weird Tales found a more familiar figure alongside the usual crowd of ghouls, corpses, and scantily clad women. The cover story of the May–June–July issue was “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs,” by none other than Harry Houdini. The magician tells of his voyage to Egypt, where he is captured by nefarious locals and imprisoned beneath a pyramid, to be sacrificed to horrid monsters of untold age. With his trademark skills, Houdini frees himself and reaches the surface, insisting—despite his injuries—that it was nothing more than a dream.

Fans of horror fiction know this bizarre story under a different name and authorship: H. P. Lovecraft’s “Under the Pyramids.” Each in their own way icons of early twentieth-century America, Lovecraft and Houdini led strikingly different lives. The magician was an international celebrity, drawing rapturous crowds wherever he went. He performed for the Russian royal family. He amassed a personal fortune sufficient to purchase, among other things, a dress once worn by Queen Victoria (a gift for his mother) and a 1907 Voisin biplane (complete with mechanic). His funeral was attended by two thousand members of the public. By contrast, Lovecraft’s biographer S. T. Joshi holds that the writer “as he lay dying […] was envisioning the ultimate oblivion that would overtake his work.” All but one of his stories were unpublished or moldering away in back issues of pulp magazines. It was only posthumously that his writings found their audience, eventually attaining the cult status they enjoy today.

H. P. Lovecraft in 1934 (photograph by Lucius B. Truesdell)

The original idea for “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” came from Houdini, whom the proprietor of Weird Tales, J. C. Henneberger, had retained as a columnist to boost flagging sales. Henneberger and Edwin Baird, the magazine’s editor, tapped Lovecraft to ghostwrite what Houdini was claiming to be a true story. “Lovecraft quickly discovered that the account was entirely fictitious, so he persuaded Henneberger to let him have as much imaginative leeway as he could in writing up the story” (Joshi, A Dreamer and a Visionary, 191).

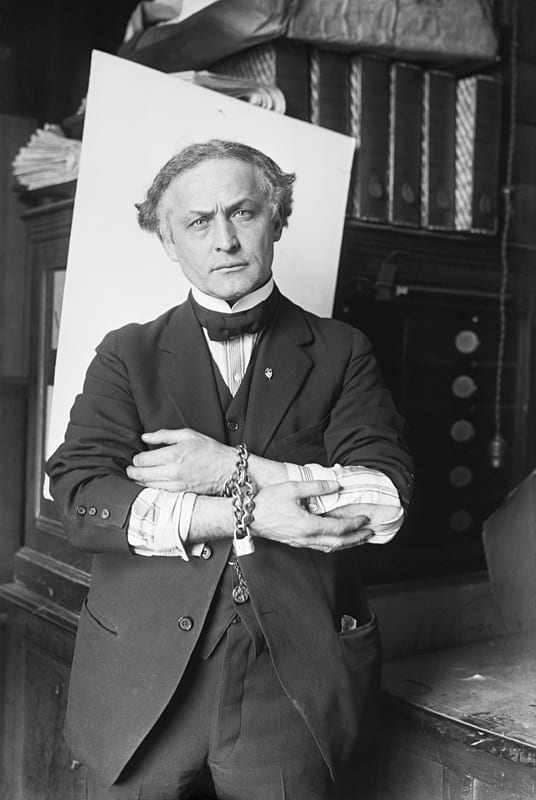

“Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” was by no means Houdini’s only fictional exploit. As early as 1906, he had been making films of his tricks, and between 1918 and 1923 starred in and/or produced several silent movies. Though these films do not present themselves as Houdini’s own experiences, there was little attempt to hide the fact that the magician was their raison d’être and main selling-point. Their protagonists—given telling names like Harvey Hanford or Harry Harper—spend most of their time onscreen being straitjacketed, chained, thrown into rivers, suspended from airplanes or cliffs, or otherwise discomfited so as to give audience the greatest possible opportunity to see Houdini do what he did best.

Harry Houdini in 1918

Lovecraft understood that readers wanted Houdini the escape artist, and he obliged. During a nocturnal visit to the Pyramids, “Houdini” is attacked, bound, and into the deep recesses of an underground temple. Our hero is undaunted.

The first step was to get free of my bonds, gag, and blindfold; and this I knew would be no great task, since subtler experts than these Arabs had tried every known species of fetter upon me during my long and varied career as an exponent of escape, yet had never succeeded in defeating my methods.

At the same time, the story bears all the hallmarks of Lovecraftian “cosmic horror”: ghastly and ancient things lurking beneath ordinary life, grotesque monsters compounded from all manner of anatomies and mythologies, the inability of the human mind to comprehend the awful truth, and his unique—to put it kindly—prose style.

It was the ecstasy of nightmare and the summation of the fiendish. The suddenness of it was apocalyptic and daemoniac—one moment I was plunging agonisingly down that narrow well of million-toothed torture, yet the next moment I was soaring on bat-wings in the gulfs of hell; swinging free and swoopingly through illimitable miles of boundless, musty space; rising dizzily to measureless pinnacles of chilling ether, then diving gaspingly to sucking nadirs of ravenous, nauseous lower vacua. . . . Thank God for the mercy that shut out in oblivion those clawing Furies of consciousness which half unhinged my faculties, and tore Harpy-like at my spirit! That one respite, short as it was, gave me the strength and sanity to endure those still greater sublimations of cosmic panic that lurked and gibbered on the road ahead.

Lovecraft’s reputation is rightly tarnished by his racism. Though “Under the Pyramids” is by no means the worst offender within his corpus, Egypt offered ample scope for his prejudices: “the crowding, yelling, and offensive Bedouins,” “squalid Arab settlement,” “filthy Bedouins.” The orientalist mode is out in force, as “Houdini” and his wife arrive in Cairo only to be disappointed that “amidst the perfect service of its restaurant, elevators, and generally Anglo-American luxuries the mysterious East and immemorial past seemed very far away.” Once they journey deeper into the city, they find what they are looking for—“in the winding ways and exotic skyline of Cairo, the Bagdad of Haroun-al-Raschid seemed to live again.” Lovecraft summons every trope of the orientalized Middle East: bazaars and camels, secret tombs and perfidious natives, the call of the muezzin and the scent of spice and incense. Egypt, “Houdini” is told by one of his captors, “is very old; and full of inner mysteries and antique powers.”

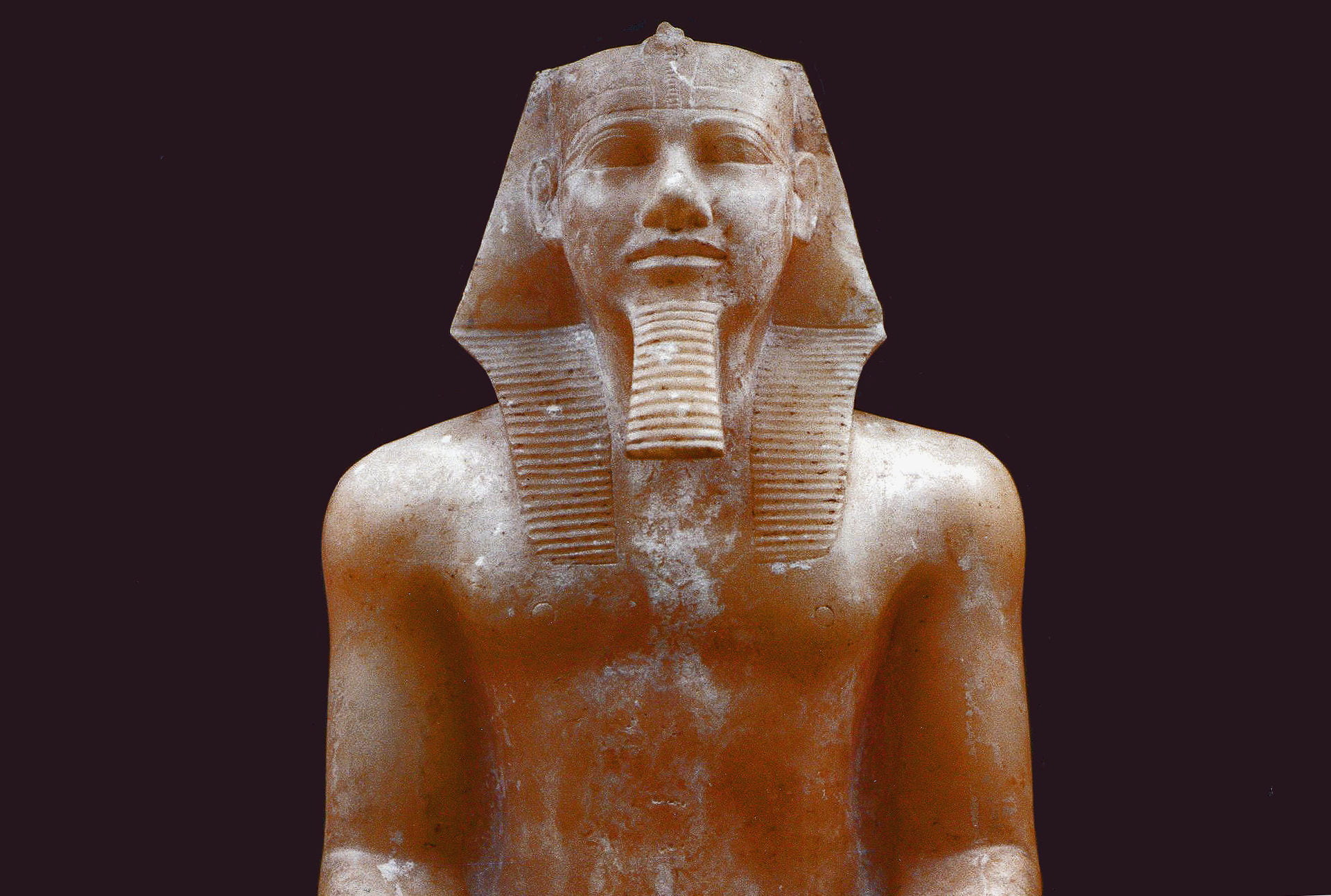

Statue of Khafra, Egyptian Museum, Cairo (photograph by Juan R. Lazaro)

Within these fantasies, however, are a few kernels of genuine Egyptiana. The figureheads of “Houdini’s” Egypt, for instance, are the undead “King Khephren and his ghoul-queen Nitokris,” who reign over a legion of unnatural things. Denuded of Lovecraft’s nightmarish trappings, both are historical personages with unsavory reputations. “Khephren,” usually known as Khafra, was the builder of the second-largest pyramid at Giza and (probably) the Great Sphinx, but Herodotus and other ancient historians remember him as a cruel and heretical ruler who closed Egypt’s temples and plunged the land into misery (II.127–28). Nitocris is the subject of Egyptological debate: some scholars accept ancient accounts naming her as a pharaoh of the late Sixth Dynasty (2345–2181 B.C.E.), others deny her very existence. Describing his unease near even the smallest pyramid, “Houdini” explains, “was it not in this that they had buried Queen Nitokris alive in the Sixth Dynasty; subtle Queen Nitokris, who once invited all her enemies to a feast in a temple below the Nile, and drowned them by opening the water-gates?” An anecdote worthy of the horror writer, to be sure, but not his invention. Herodotus relates how Nitocris avenged herself on her brother’s killers:

She built a spacious underground chamber; then […] she gave a great feast, inviting to it those Egyptians whom she knew to have been most concerned in her brother’s murder; and while they feasted she let the river in upon them by a great and secret channel. This was all that the priests told of her, save that also when she had done this she cast herself into a chamber full of hot ashes, thereby to escape vengeance. (II.100, trans. A. D. Godley)

The association of Nitocris with the Pyramid of Menkaure, third and smallest of the Pyramids of Giza, comes from the priest-historian Manetho (early third century B.C.E.). He calls Nitocris “the noblest and loveliest of the women of her time, of fair complexion, the builder of the third pyramid” (The History of Egypt, 55).

Though Houdini is (justifiably) remembered more fondly than Lovecraft, his career was by no means free from discomfiting racial politics. John F. Kasson links Houdini to Tarzan, early bodybuilders like Eugen Sandow, and others, as focal points of anxiety about the white body. In this and in many other respects, the superstar magician and the obscure writer had more in common than might be suspected. Both cultivated a supernatural mystique—in which neither believed—personas that took on lives of their own. Both sought to satisfy an early twentieth-century hunger for excitement. Certainly, the two men got on well: Houdini asked Lovecraft to write a now-lost article about astrology and tried (unsuccessfully) to help the young writer secure employment with a newspaper. They were planning to collaborate, with Lovecraft’s friend and fellow pulp author C. M. Eddy, on an anti-spiritualist book, The Cancer of Superstition, when Houdini died on October 31, 1926. Only Lovecraft’s outline and thirty-odd pages of Eddy’s manuscript survive—together with “Under the Pyramids” the only witness to the strange partnership of the magician and the horror writer.

July 25, 2017 at 12:31 pm

This story would not have stood out in the pulp magazines of the day on account of orientalism and racism, I’m sorry to say. Pulp magazines were riddled with ethnical clichés.

September 21, 2017 at 2:07 pm

Very interesting – I’d have never guessed about the Houdini-Lovecraft connection, especially because of Lovecraft’s anti-semitism. And I never read the pyramid story, although I’ve read lots of Lovecraft. Thanks for posting this educational and engaging essay.