By guest contributor Dr. Dina Gusejnova

Editors’ Note: We are pleased to present a series of multi-media reflections on centenaries of the Russian Revolution by Dina Gusejnova, which will run for three weeks. The editors would welcome proposals for future audiovisual pieces.

[wpvideo mf06wfHz]

Entrance to the Revolution exhibition at the British Library (photograph by Georgios Giannakopoulos)

Since August 2014, centenaries have been hard to avoid. And there is no end in sight until at least 2019. London easily beats other European cities as the capital of European centenary-mania. A few years after the monumental poppies of World War I have left us, London has been truly taken over by the year 1917. Just as one ‘Revolution’ closed at the Royal Academy, another one opened at the British Library, and this is to name just two of the biggest public institutions. Revolutionary posters pursue you through the dark tunnels of the tube. Reproduced and sold on fridge magnets, notebooks, cushions and silk shawls, 1917 has become a family of brands.

[wpvideo YBc9ydqh]

Time itself has become a commodity—but not everywhere. You might think, with John Reed, that “no matter what one thinks of Bolshevism, it is undeniable that the Russian Revolution is one of the great events of human history, and the rise of the Bolsheviki a phenomenon of world-wide importance.” Not so in Russia, however, which shows no evidence of a five-year centenary plan, even though anticipated celebrations of the centenary and other anniversaries of the revolution had been an integral part of Bolshevik propaganda since the 1920s. Gingerly is not an adverb one would associate with any Russian government, yet this is the only way to describe the official approach to the centenary of the Revolution. How easy it is for the Royal Academy to tell the story of the revolution in and through Russian art from its futurist cradle to the GULAG, inviting the consumer to float out towards Piccadilly, supposedly breathing a sigh of relief!

In Russia, no major public institution has been in a rush to commemorate—despite the fact that a historian is now the country’s Minister of Culture, one who had participated in anticipatory discussions of the centenary only five years ago. To be on the safe side, Moscow’s New Tretyakov Gallery has put on a major art show devoted to the Thaw era, the age of post-Stalinist reconstruction and socialist consumer design. Access to the building is through the nearby park of discarded monuments, a tourist attraction dating back to the 1990s, replete with discarded Soviet leaders and Chekists, notably Stalin and Dzerzhinsky. But this is certainly not part of the concept behind the exhibition: Lenin remains unburied, and on the streets and in the Kremlin, the Chekists are alive.

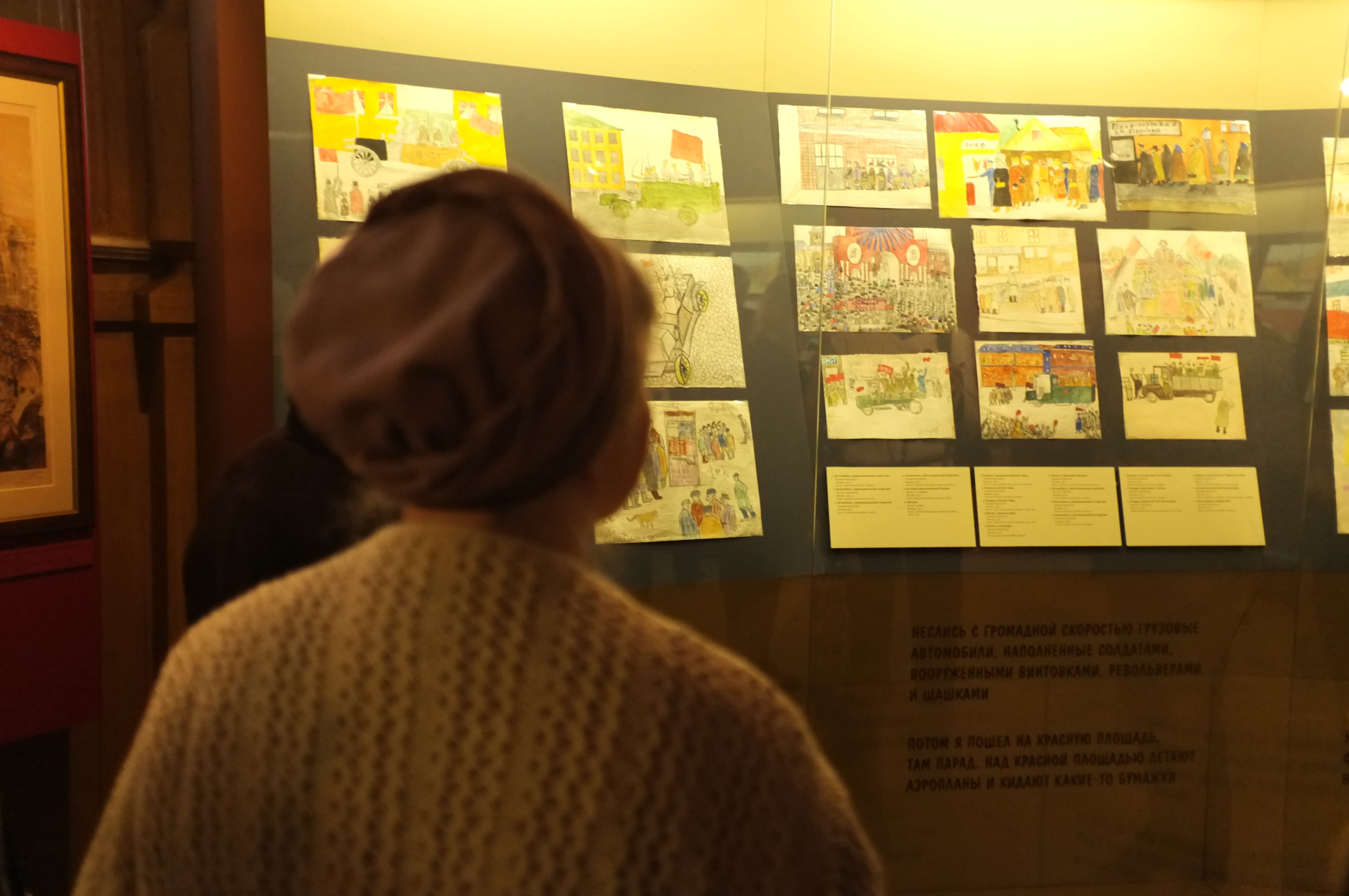

Visitor looking at the exhibit “The February Revolution through children’s eyes,” April 2017 (Photo by Dina Gusejnova)

As for the Moscow State Historical Museum, located at 1 Red Square, the only revolution-themed hall it has so far opened is a special exhibition about the February Revolution, as seen by the children of one of imperial Russia’s last gymnasia, with most of the other programming done through discussion evenings and film screenings.

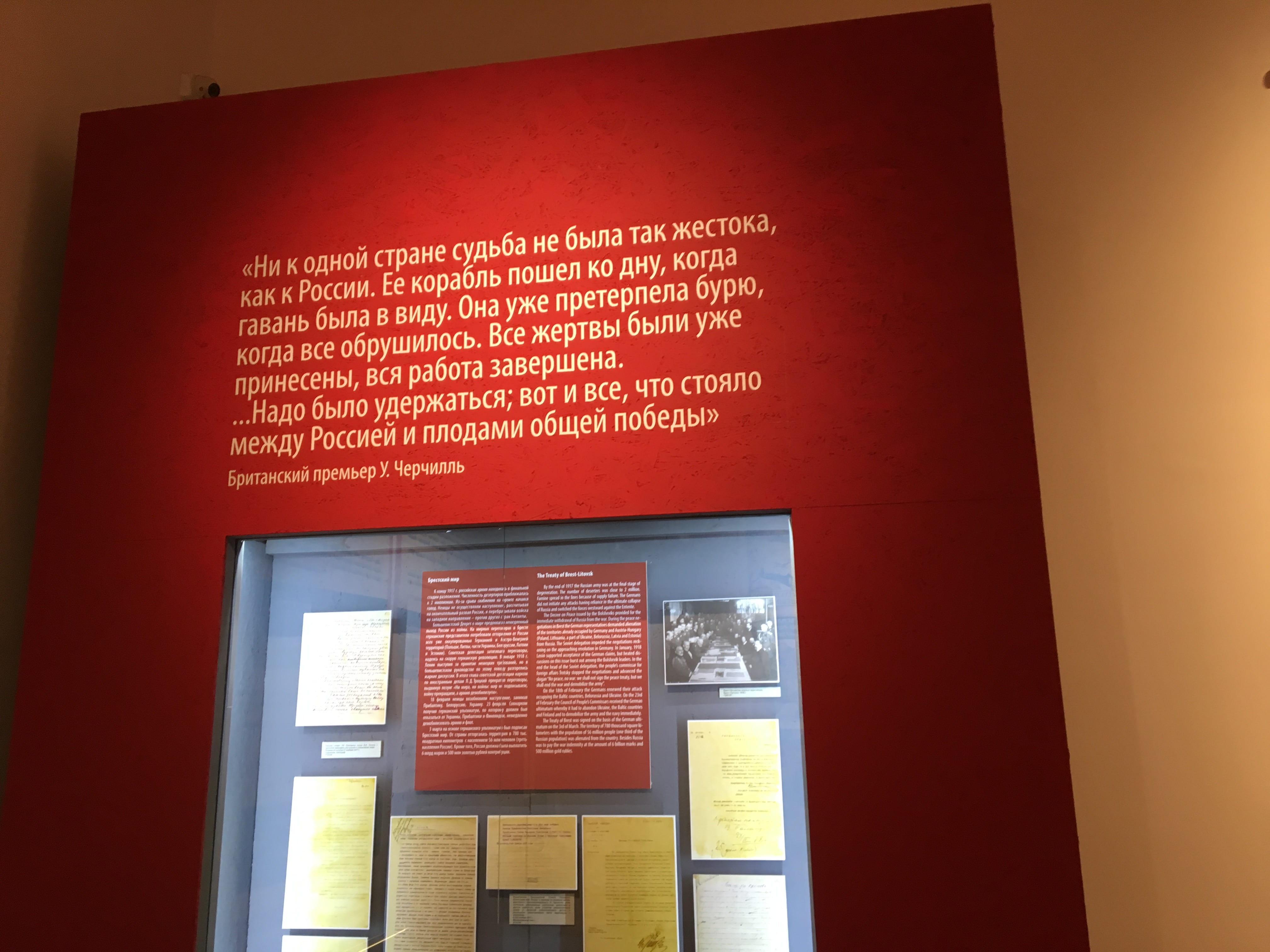

Its sister museum, the Museum of Contemporary History (formerly the Museum of the Revolution), did update its exhibition with a modern design, but the narrative leads nowhere: a few flags and caricatures here and there, some quotes from Lenin, more still from his conservative and Orthodox critics and—perhaps most jarringly—from Winston Churchill:

Exhibition “1917-2017” at the Moscow Museum of Contemporary History, April 2017 (Photo by Dina Gusejnova)

To no state in the world has fate been crueler than to Russia. Her ship began to sink with the port already in sight. She has already experienced a storm, when all collapsed. All the sacrifices had already been made, all the work had been completed. […] Perseverance was called for; this is all that stood between Russia and the fruits of a common victory (trans. Dina Gusejnova).

Commentators have already discussed the reasons for the awkwardness about the revolution in Russia, and the way it reflects Russia’s current political situation. I have put it critically, but it is actually understandable: the British public appears in the role of a confident purveyor of another society’s crisis, whereas for the Russians, the crisis has never really ended. Marking a revolution can be nearly as dangerous a notion as making one. And how should a state mark an event which was supposed to lead to its withering away?

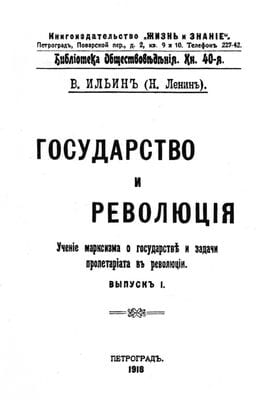

Title page to the first edition of Lenin’s The State and Revolution (Petrograd, 1918), published under the pseudonym V. Ilyin

By contrast to state-sponsored institutions, some of the most thoughtful reactions to the centenary have included translations of poetry and prose, reflecting a wide range of views in the revolutionary era, in Britain; and privately funded digital public platforms inviting visitors to identify their own position on the political spectrum of 1917, in Russia. In a poem composed in September 1914, the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam had written: “Imperial Europe! Ever since Bonaparte / was in the bullseye of Prince Metternich’s quill / For the first time in a century, we will / Witness your wondrous map taken apart!” (trans. Dina Gusejnova). Looking back towards 1814, Mandelstam did not see much of the twentieth century. Exactly two hundred years later, the map of Europe started to change once again, with Russia’s annexation (or re-annexation, as some might say) of Crimea. Tragically, instead of an exhibition to the memory of the First World War, in 2014 Russia had opened a new actual western front, and the conflict is still with us.

In 1922, Mandelstam had, once again, presciently exclaimed: “Beastly aeon, who will dare / Look you in the eye / Glue your back with their own blood/ Two centuries, bone for bone” (trans. Dina Gusejnova). And this was only in 1922! In that year, the fashionable English Club in Moscow, once frequented by Leo Tolstoy and other anglophile dandies, had just been requisitioned and turned into a Museum of the Revolution. It attracted foreign enthusiasts and revolutionary bien pensants such as George Bernard Shaw and Sidney and Beatrice Webb. By 1938, Mandelstam had perished in a camp, a fate which the translator Robert Chandler contextualizes in his evocative introductions to two hundred years of Russian poetry.

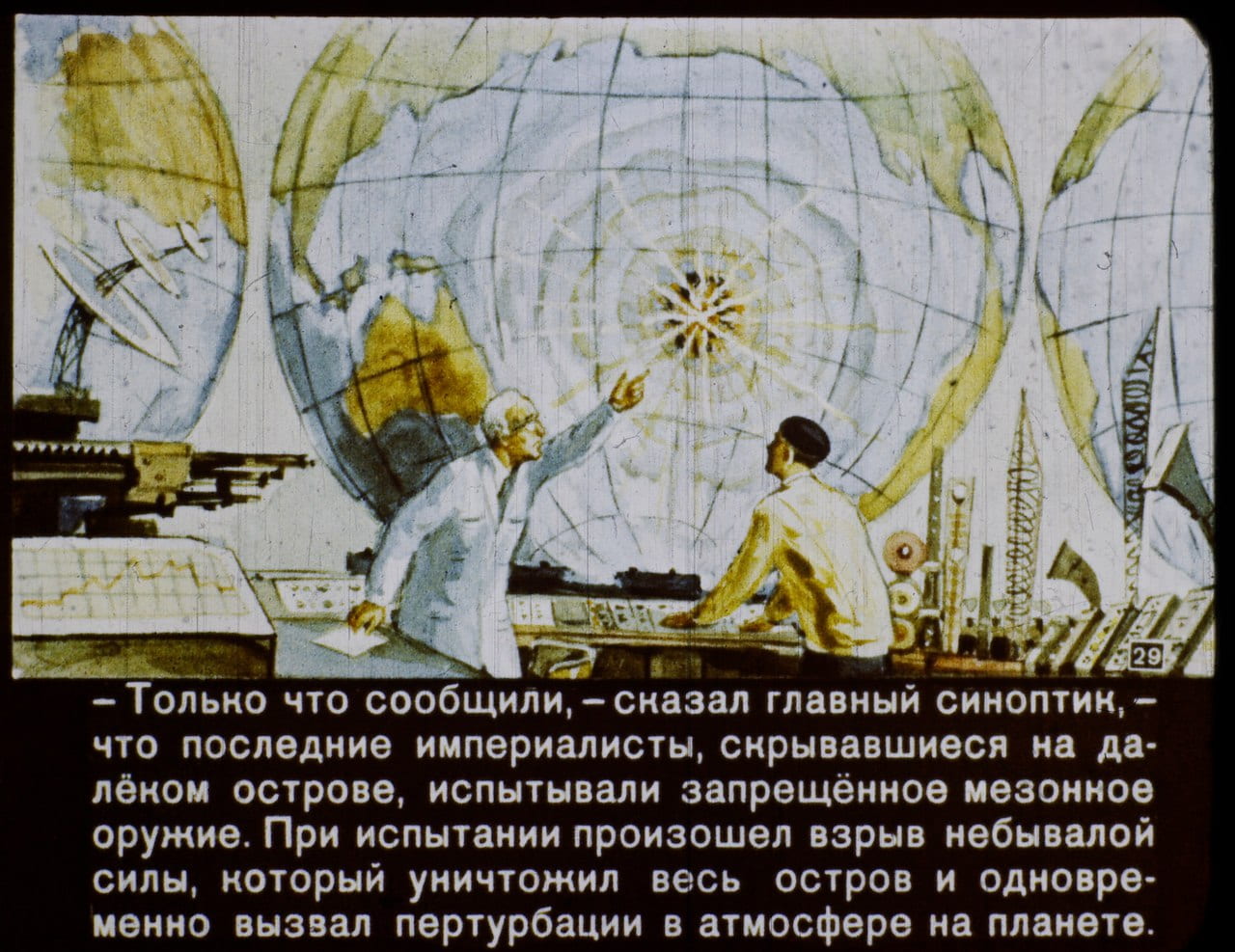

Among the most emblematic documents of later Soviet “horizons of expectations,” a term which Reinhart Koselleck made popular to describe past ideas of the future, is a children’s slideshow produced in 1960, which has recently gone viral online. In it, we can see how the state-sponsored media of the post-Stalin era had become increasingly optimistic about the prospects for the future. In 2017, they showed, the Soviet capital would embark on its preparations to celebrate the centenary, just as the world’s “last imperialists” self-imploded on a remote island, falling victims to their own weapon of mass destruction.

L. Smekhov, In 2017 (https://tjournal.ru/39410-kakim-videli-2017-y-v-sovetskom-diafilme-1960-goda)

“‘They have just reported,’ a meteorologist said, ‘that the last imperialists, who had been hiding on a remote island, have been testing the meson bomb [a type of nuclear weapon that Soviet intelligence believed was being developed by the Americans]. During the test, an explosion of an unprecedented scale occurred, destroying the whole island and causing turbulences in the entire atmosphere.’”

“The meteorological station for remote weather control quietly floated above the city. The rejoicing capital was preparing for the 100th anniversary of Great October. These festivities coincided with the victory of Soviet science over nature.”

“In the evening, Evgeny Sergeevich turned on his televideophone and called the steamer Kakhetia. His wife smiled from the screen, and Nina stood next to her and shouted: ‘Daddy, we’ve been having some nice, warm rain here!’”

As we know, things turned out differently: the “televideophone” belongs to the realm of the “imperialists”—and so does Russia itself; but the Georgian region of Kakhetia, once part of the Soviet Union, does not belong to the Russian Federation.

All too often, when we think about anniversaries, we naturally think about time. And yet thinking about space opens new prospects on our relationship to the past. After all, our political “horizons of expectations” and “spaces of experience” are rooted in a spatial imagination.

The more we see centenaries in geographical perspective, the more we recognize the diversity of views on this issue. The idea of a common commemorative mentality is a fiction: we remain divided in our attitudes to centenaries by place, generation, and so many other circumstances. The private, Proustian mémoires involontaires, the exposure to certain sounds, sights, sensations, or ideas, can overpower any official attempts to mold a common attitude to the event.

I have begun speaking about this to colleagues who had themselves travelled to different locations to engage with thoughts on revolutions and centenaries. I chose to concentrate my conversations around two contrasting spaces, the museum and the public square. Site-specific thinking about centenaries should not just be about cities or states, but also about spaces within cities and even houses. How do our thoughts change when we are placed in a museum, in a public space, in a private living room? How do we reconfigure our ideas of the past and its links to our present?

Dina Gusejnova is Lecturer in Modern History at the University of Sheffield. She is the author of European Elites and Ideas of Empire, 1917-57 (Cambridge University Press, 2016) and the editor of Cosmopolitanism in Conflict: Imperial Encounters from the Seven Years’ War to the Cold War (Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming later in 2017).

August 9, 2017 at 10:25 am

Reblogged this on Project ENGAGE.