By guest contributor Christopher B. Lowman

If you have a smart phone handy, take a look at your phone application icon: when was the last time you saw a receiver shaped like that? Even the language associated with phones reflects physical actions no longer required: there is no dial to “dial,” and no hook on which to “hang up.” Think about this too: when taking a photograph on a phone, the sound effect is still that of a “kachunking” camera shutter, despite its absence. These are all symbols that have outlasted their original functional counterparts.

Visual or auditory symbols that retain aspects of older, defunct design are called skeuomorphs. In the last decade, the heavy use of visual metaphors in Apple’s iOS led to discussions of skeuomorphism’s definition, and its pros and cons. Listicles of skeuomorphs and other visual metaphors have been popular reading on Mental Floss and other design blogs. Skeuomorphism is not just digital: it also describes physical objects retaining material characteristics no longer functionally necessary. Horsepower describes the capabilities of vehicles long since stripped of accompanying horses. Patterns of circular holes in concrete structures, formerly imprints from the pouring process, continue to be made even when not all processes require them. Skeuomorphs can be “found in nature as well”: the orchid Ophrys apifera produces flowers shaped to attract Eucera bees, even though the bees have disappeared from much of the plant’s modern range, as illustrated by xkcd. This illustrates how skeuomorphs can occur without intention, yet still indicate an object’s origins through no longer functional physical phenomena.

Despite the popularity of the term to describe digital design, its origins have more to do with artifacts than phone applications. Dr. Dan O’Hara at London’s New College of the Humanities described skeuomorphism as “unintentional side-effects of technological evolution.” It is in this evolutionary sense that skeuomorphs become useful to anyone interested in the history of material culture: as O’Hara put it, “skeuomorphs, as a kind of ‘memory’ capacity of artifacts, can show us the processes that guide the evolution of the forms of technology.” A look at the Google Ngram Viewer, which gauges the popularity of a word over time based on publications in Google Books, reveals that “skeuomorph” was in use at the turn of the twentieth century. Henry Balfour in The Evolution of Decorative Art (1893) and Alfred Cort Haddon in Evolution in Art: As Illustrated by the Life-histories of Designs (1907), among others, used skeuomorphs as crucial evidence for studying object designs over time. For example, Balfour, the first curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, described how indigenous people in the Andaman Islands had traditionally used large shells as plates, and continued to make wooden plates with decoration recalling shells (1893, 114).

Academic interest in skeuomorphs was rooted in some of the hierarchical assumptions that defined much of nineteenth century anthropology. Skeuomorphs offered evidence of change in the types and materials of objects over time; this played into what many anthropologists believed to be a universal and linear evolution of human culture. Haddon specifically uses skeuomorphs to describe supposedly universal material transitions, such as tapa giving rise to matting, and basketry giving rise to pottery (1907, 116). Both archaeology and ethnography developed as disciplines guided by the assumption of cultural evolution, that studying “primitive” people would reveal linear developments toward “civilization,” defined as Western European cultures. Balfour describes his work as the “study of the Art of the more primitive of the living races of mankind, with a view to explaining, by a process of reasoning from the known to the unknown, the first efforts of Primaeval Man to produce objects which should be pleasing to the eye” (1893, v). This conflation of past and contemporary cultures drove ethnographic interest in the collection of objects for museums, particularly from cultures believed to be on the verge of disappearing.

Are skeuomorphs still useful for the study of material culture? Doing away with the assumption that material changes imply progression toward any particular cultural zenith, the study of skeuomorphs continues to reveal chronologies of connections between objects and people. Archaeologists use them to discuss invention, innovation, and replication (Knappet 2002, Blitz 2015), especially across cultures (Howey 2011). An example of this is a type of lacquer cup called a tuki, used in religious ceremonies by the Ainu, the indigenous people of Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kurile Islands north of Japan. Comparisons of different tuki over time indicate origins and meanings invisible when any one example is considered by itself.

In traditional Ainu religion, any physical being or thing that can perform in ways that humans cannot is considered a god, or kamuy. Kamuy could only be contacted through the use of specific instruments, including carved wooden prayer sticks called ikupasuy, and cups, called tuki, which held offerings of sake. Ikupasuy would be dipped into tuki and drops of sake scattered to please kamuy.

Two Ainu men using prayer sticks (ikupasuy) and lacquer cups (tuki) in prayer. Photography by Burton Holmes from Ewing Galloway, 1917.

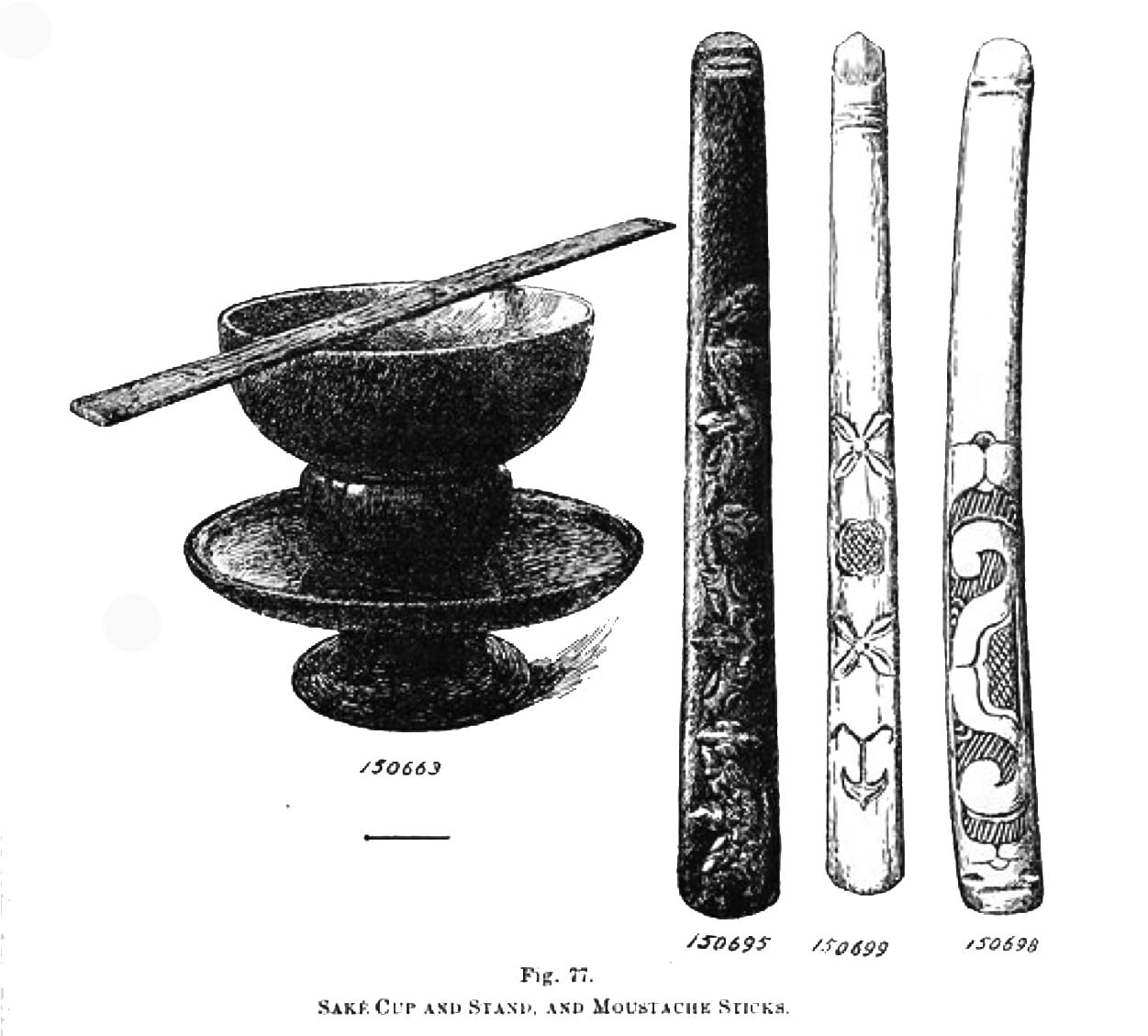

Nineteenth century visitors to the Ainu mistakenly called ikupasuy “moustache sticks” because the Ainu prayer ceremony involved lifting both cup and stick together toward the mouth, leading observers to assume the purpose of the stick was to lift the moustache when drinking. The uniqueness of ikupasuy led to them becoming prized by collectors. When Romyn Hitchcock conducted his collecting trip for the Smithsonian Institution in 1888, his pursuit of ikupasuy earned him the name “Mr. Moustache Stick” while in Hokkadio (Houchins 1999, 149-150). Anthropologist Frederick Starr, who helped to organize the Ainu exhibit at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, also stated that ikupasuy “had a great attraction for us and we secured scores of them” (Starr 1904, 65). While museum collections contain dozens of ikupasuy, tuki were rarely collected: fewer than a dozen were collected for United States museums prior to 1920.

Romyn Hitchcock’s illustration of ikupasuy and tuki, from “The Ainos of Yezo” in Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, 1890, 459.

The reason for the cups’ absence from collections is connected to the same theories that drew nineteenth century anthropologists to study skeuomorphs. Anthropologists lacked interest in tuki because they were trade goods rather than Ainu-made. Ainu lacquerware, including tuki, was acquired through trade with the Japanese, particularly the Matsumae clan. Exchange ceremonies appear in Japanese paintings, such as this one by Hirasawa Byōzan from 1876. However, anthropologists seeking only “pure” Ainu culture systematically ignored trade items. Anthropologist Stewart Culin dismissed lacquer and swords among the Ainu, believing that “not one of them have any artistic or pecuniary value” (75). Why was this? Recall that according to cultural evolution theory, so-called “primitive” cultures were understood as keys to the collective human past. Trade items like the tuki were corruptions: they clouded the anthropologists’ ability to observe supposedly preserved past practices. Ikupasuy were fascinating because they seemed to stem from Ainu material culture alone. Since trade items did not fit within a pure progression, but seemed wholly introduced from another culture, items like tuki were believed to lack research value.

Tuki made of brass and ornamented with the mon of the Matsumae clan. Catalog No. 70/4223, Courtesy of the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History.

However, tuki do possess skeuomorphic properties that are clues to their changing significance as they passed from a Japanese to an Ainu context. Japanese crests, called mon, adorned possessions belonging to noble houses (for example, the diamond motifs on the banner in this 1867 image of an Ainu ritual welcoming Matsumae merchants). While some tuki have none, or only single mon, others are decorated with multiple mon from different noble houses. Why would this be? One explanation is that Ainu interest in acquiring highly decorated lacquer may have outweighed the Japanese social meaning of the mon. Linguistic evidence of the importance of shining things and metallic surfaces is preserved in Ainu words such as “treasure,” ikor, literally “shining things,” or “metal,” kane, a word used as a synonym for “magnificent,” and used to describe tuki specifically in Ainu epic poetry (Phillipi [1979] 2015). The shining decorations, that in a Japanese context represented noble ownership, were appreciated for aesthetic reasons once in Ainu hands, which in turn changed the way Japanese artisans applied the mon during production.

Wooden tuki and ikupasuy on display in the Ainu Cultural Center, Sapporo. Photograph by the author, August 2016.

In addition to decoration, the shape of tuki influenced Ainu woodcarvers, who produced their own skeuomorphic versions out of new materials. In one example, a carver created a tuki and stand from wood, which were subsequently lacquered by a Japanese artist. Others, like the one pictured above from the Ainu Cultural Center in Sapporo, are decorated wood without any lacquer but still retain the same vessel form. While the Ainu possessed other styles of cups, tuki specifically were made in the shape of Japanese lacquer cups and stands.

Tuki are an example of an object transformed through cultural context—a decorative cup that became integral to religious practice once in Ainu possession. Viewed over time, the transformation is a physical one as well, as they accumulated decorations that transformed in meaning because of an Ainu, rather than a Japanese, aesthetic. The shape of the lacquer vessels was preserved even as the Ainu produced tuki out of new materials. Tuki as skeuomorphs show how objects simultaneously influence and are influenced by their cultural context, and how their form and material act, as Dan O’Hara said, with a capacity for memory.

Christopher B. Lowman is a graduate student in the Anthropology Department at the University of California, Berkeley. His research focuses on intersections between historical archaeology and museum anthropology, with a focus on immigration, colonialism, and the history of museums.

Leave a Reply