By Contributing Editor Eric Brandom

Mme Forestier, who was playing with a knife, added:

–Yes…yes…it is good to be loved…

And she seemed to press her dream further, to think of things she dared not say.

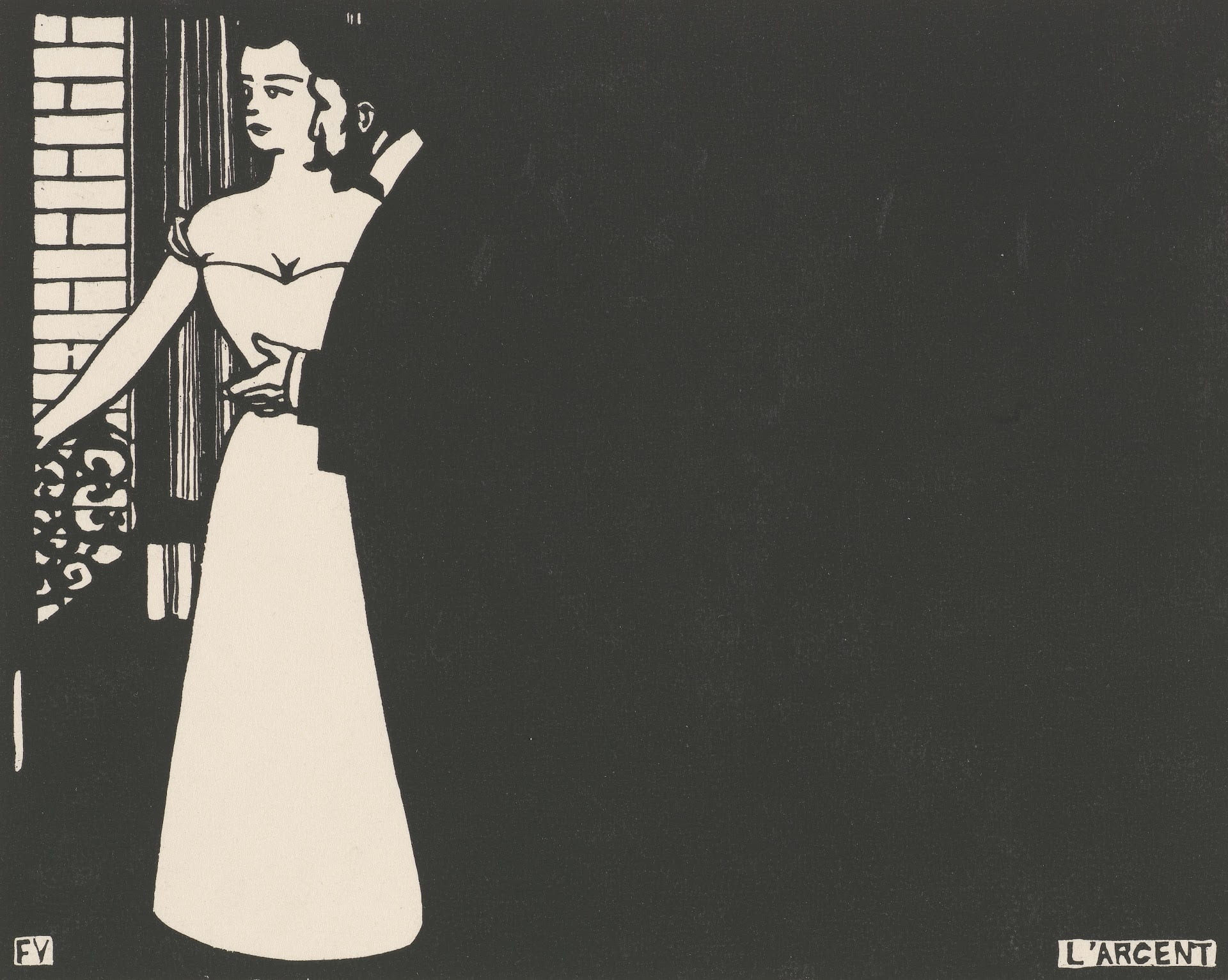

“L’argent” (“Money”), from Félix Vallotton’s series “Intimités” (image credit: Van Gogh Museum)

These are lines from a dinner scene early in Guy de Maupassant’s 1885 Bel-Ami (I have consulted, but in places substantially modified or replaced, the Sutton translation). The novel follows the talentless and superficial George Duroy—eventually Du Roy, since the sparkle of aristocracy is all the more fascinating en République—as he makes his social ascent through seduction, daring, and a little judiciously applied journalism. Duroy is driven by desire, especially for wealth, status, to be adored by people in general, and to possess women. His lack of moral feeling for anyone but himself means that he is able to make good use of his one real advantage, which is that women find him uncommonly attractive. Robert Pattinson played him, perhaps without the requisite physicality, in the 2012 film. In this post, I want to think about violence in Maupassant’s novel. Indeed I would like to use the experience of reading to give historical depth and complexity to the notoriously ambiguous and freighted concept of violence.

Bel-Ami is a rich text, taking as major themes not only great passion betrayed, but also journalism, gender, and colonial politics in the early Third Republic. It does not appear particularly violent compared to, for instance, Zola’s Germinal (1885), which breaths misery and social politics from every page, or the same author’s Nana (1880), also about an implausibly sexually attractive individual. For just this reason it seems to me that we may learn something from Maupassant about what counts as violent, what registered as dangerous violence in the Third Republic. As the lines quoted above suggest, violence is by no means absent here. Violence is both presented to the reader in the action of the plot, often at an ironic distance, and also is an effect produced in the reader. These two sorts of violence do not line up. So here I consider several “violent” incidents, including those that are physically—manifestly or naively—violent and those that are not. Indeed it seems to me that it in this novel, and perhaps in the larger society out of which it came, we might look for the most dangerous violence at the juncture of what is spoken and what one does not dare say, of the public and the intimate.

Bel-Ami opens with Duroy as flâneur, going down the boulevard with barely enough money in his pocket to last out the month. He has a powerful thirst for a bock (beer), and covets the wealth of those he can see enjoying the pleasures of life in the cafés. He has just finished two years in “Africa” and the memories are not far away: “A cruel and happy smile passed over his lips at the memory of an escapade which had cost the lives of three men of the Ouled-Alane tribe, and secured for himself and his comrades twenty chickens, two sheep, some money, and something to laugh about for six months.” The novel’s plot is launched when Duroy by chance meets Charles Forestier, an old friend from the military. He is introduced to the borderline honorable professional of newspaper work at the fictional La vie française, owned by “le juif Walter.” We are introduced to Madeline Forestier, whose talent for political journalism and willingness to ghostwrite propelled her husband Charles into prominence, and will now do the same for Duroy.

French expansion in African is woven into the plot. Indeed the way in which the novel takes journalism in general, and the actualités of Third Republic colonial ventures in particular, as a theme is one source of scholarly interest. Duroy’s first publication in the newspaper, which meets with a success he is never able to emulate again without the assistance of Madeline, draws on his experiences in Africa. But there is a larger colonial venture in the background of the novel. Put briefly, the minister Laroche-Mathieu connives with Walter to convince the public that the French will never go into Tunisia. This has the effect of driving down to practically nothing the price of Tunisian government bonds. Then Laroche-Mathieu’s government does decide to invade, determining among other things to guarantee the solvency of the bonds. Walter turns out to own a great quantity of them. From merely wealthy he becomes among the richest men in Paris—from “le juif” he becomes “le riche Israélite.” This subplot ties the novel both to the current events of the 1880s and to Maupassant’s own newspaper career.

But colonial experience is manifest in the novel on quite other levels. Through no fault of his own Duroy becomes involved in an affair of honor, a duel with a reporter from another paper. In a darkly comic scene Duroy, who is capable of self-reflection only in the mode of self-justification, considers the ridiculous possibility that he will die. His military past returns, above all in its irrelevance: “He had been a soldier, he had shot at Arabs without much danger to himself, it is true, a little as one shoots at a boar on a hunt.” Unfortunately for him, “in Paris, it was something else.” The duel takes place, as it must; both parties fire and miss; honor is maintained. Such duels were relatively common among bourgeois men and especially among journalists on the right like Duroy. So well institutionalized was the practice of risking one’s life—even if relatively few people died—for one’s honor that it could be seized by women to criticize the gender divisions of the Third Republic. In an elaborate set piece that farcically repeats his own experience, Duroy attends a charity banquet involving a series of epée and saber duels as entertainment. One section of the spectacle is women sparring to the erotic delight or forbearance of all.

The violence of Algeria has no existential weight for Duroy, as little as do the semi-nude fencers. This has not to do with the victims (Duroy has no feelings for anyone beyond himself, Ouled-Alane or French, man or woman) or more surprisingly even with the objective risk of death.In Paris, there are other men looking at him. It is fame, unequal recognition—to seduce Paris—that Duroy really wants. The duel is violence that does not take place, mere potential violence, as meaningless as the long late-night monologue in which the poet-columnist Norbert de Varenne spills out to Duroy all that he has learned about life and death.

The duel, staged and public, is a comic event for the reader and, at least as he tells it in retrospect, for Duroy. But there are also many moments of intimate violence that are less comical. Charles Forestier succumbs to a long-term illness, and Duroy proposes himself to Madeline as a replacement at the deathbed. Eventually, she agrees. Later, however, Madeline stands in the way of Duroy’s plans to marry Suzanne, the prettier of the now fabulously wealthy Walter’s two daughters. But how to rid one’s self of a wife? Duroy brings in the police to make a public discovery of Madeline in a compromising situation with Laroche-Mathieu, and force a divorce (this, too, was topical–debates around its legalization in 1884 were intense). Duroy breaks down the door to the furnished apartment and the police commissioner follows him in. The policeman demands an account of what has obviously been going on from Madeline. When she is silent: “From the moment that you no longer wish to explain it, Madame, I will be obliged to verify it” (“Du moment que vous ne voulez pas l’avouer, madame, je vais être contraint de le constater”). Duroy is able to turn the revelation—which of course is nothing of the sort—to his own advantage not only by divorcing Madeline but also, in a series of newspaper articles, by destroying the career of Laroche-Mathieu.

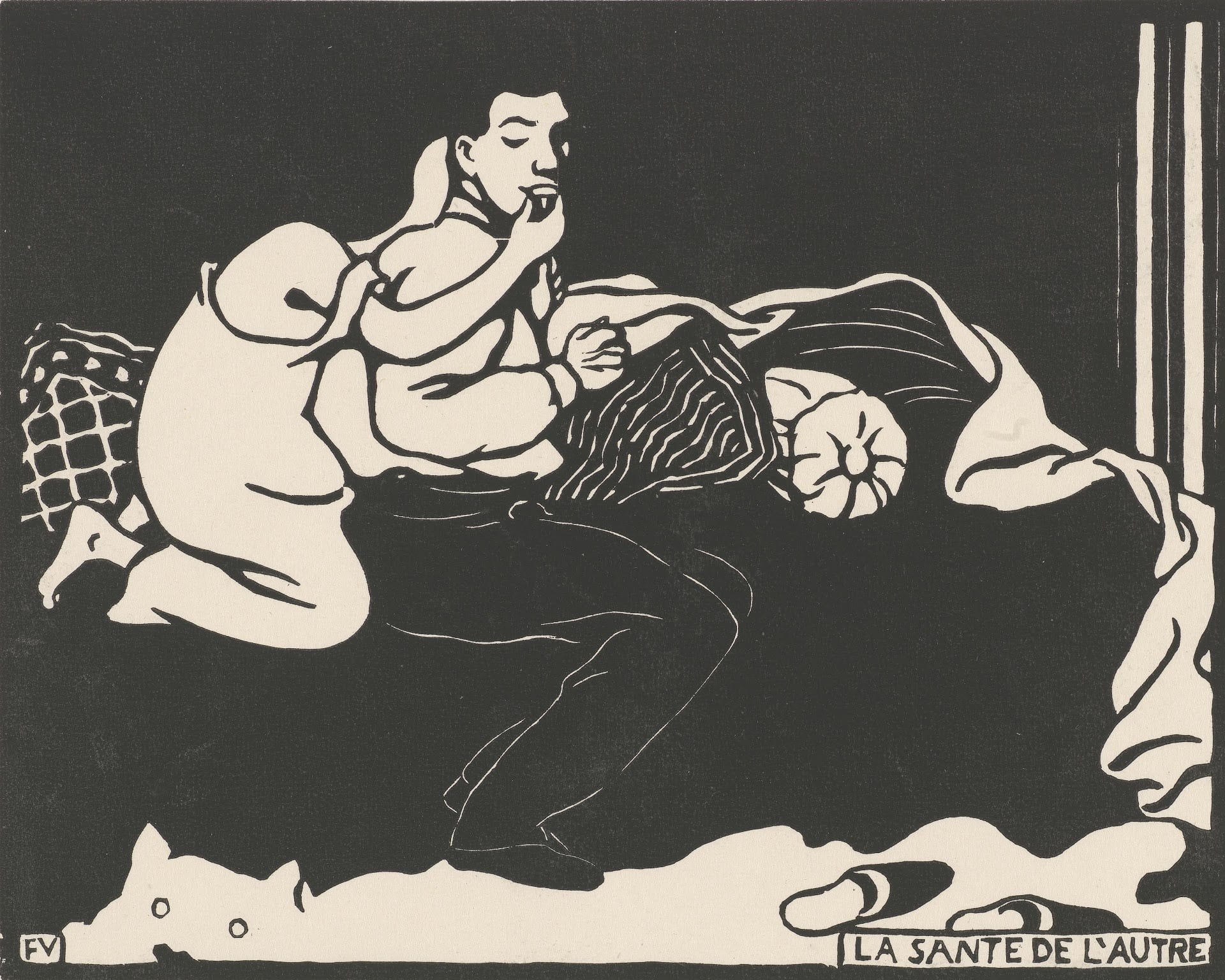

“La santé de l’autre” (“The Health of the Other”), from Félix Vallotton’s series “Intimités” (image credit: Van Gogh Museum)

This elaborately public scene with Madeline is to be contrasted with the scene between Duroy and his longtime mistress and benefactor, Clotilde de Marelle. They are together in the apartment that she rented for that purpose long ago; she has just learned, elsewhere, about his impending marriage to Suzanne Walter. Marelle, processing what he has done, how he has kept her in the dark about the plan, abuses him: “Oh! How crooked and dangerous you are!” He gets self righteous when she describes him as “crapule” and threatens to throw her out of the apartment—a miss step because she has been paying for the apartment all along, from back when he had no money at all. She accuses him of sleeping with Suzanne in order to force the marriage. As it happens, Duroy has not and this, it seems, is a bridge too far—at least so he can tell himself. He hits her; she continues to accuse him, “He pitched onto her and, holding her underneath him, struck her as though he were hitting a man.” After he recovers his “sang-froid” he washes his hands and tells her to return the key to the concierge when she goes. As he himself exits he tells the doorman, “You will tell the owner that I am giving notice for the 1st of October. It is now the16th of August, I am therefore within the limits.” It is almost as though Duroy was compelled to assert to a man, of whatever class, that he was “dans les limites.” As Eliza Ferguson succinctly remarks in her rich study of Parisian judicial records related to cases of intimate violence, “the proper use of violence was an integral component of masculine honorability.” In certain situations juries and even the law itself recognized that an honorable man might inflict even fatal violence on a woman. Duroy is of course not an example of honorable masculinity, but he is intensely concerned with that appearance. Familiar with his style, Marelle simply will not accept the appearance he wants to impose in the space of their intimate life. He resorts to physical violence of an extreme sort.

The only scene in the novel that does not follow Duroy in close third takes place between the Walters, when Madame Walter discovers that her daughter Suzanne has disappeared, doubtless with Duroy. Duroy, of course, had earlier seduced, used, and then grown bored of Madame Walter, a devout Catholic who had never previously done anything so immoral. Her relationship with Duroy is, again of course, unspeakable. As she explains to her husband that Duroy has made off with their daughter, Walter responds in a practical way. Rather than rage at betrayal, he is impressed by Duroy’s audacity: “Ah! How that rascal has played us…Anyway he is impressive. We might have found someone with a much better position, but not such intelligence and future. He is a man of the future. He will be deputy and minister.” His wife cannot explain the depths of betrayal she feels, at least without admitting her own culpability, so that she is rendered hypocritical even in her righteous anger. The public face of things, carefully arranged by Duroy, brings appalling suffering to the private.

![L'absoute___[estampe]___Félix_[...]Vallotton_Félix_btv1b6951702s](https://jhiblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/labsoute___estampe___fc3a9lix_-vallotton_fc3a9lix_btv1b6951702s.jpeg)

“L’absoute” (“Absolution”), Félix Vallotton (image credit: Gallica)

Leave a Reply