By Laura Doan

Read Laura Doan’s full article in this quarter’s edition of the Journal of the History of Ideas.

Marie Stopes in her laboratory (1904)

Earlier this year I spotted an article in the Guardian headlined: “Anger after nun says Mary likely to have had sex.” Sister Lucia Caram—a Dominican nun with a huge Twitter following—had received death threats from outraged viewers after stating on Spanish TV that Mary and Joseph “were a normal couple”—and “having sex” was a “normal thing.” I’m no expert on the teachings of the Catholic church but I can assure readers that whatever happened between Mary and Joseph, it was not normal. My archival evidence indicates that even a hundred years ago, most ordinary people in Britain and North America viewed the physical expression of conjugal love as part of Nature’s scheme, the moral order grounded on the assumed authority of the natural order. Sister Lucia’s translation of a story from the distant past into words current now would trigger alarm bells for most professional historians, though not all. According to one historian of the early Christian church, the fourth-century theologian St Augustine saw the marriage of Mary and Joseph as an “asexual friendship,” while another argues that Augustine understood the “normal” relations between women and men as “heterosexual love.” There are obvious advantages to narrowing the gap between then and now but we need to recognize the ways anachronistic expressions obscure how people in the past understood or talked about the sexual. In my article for JHI I explore how and when marital relations in Britain came to be configured as normal by turning to the work of a highly influential natural scientist, Marie Stopes. The history of sexual normality in Britain begins in the 1910s with the dissemination of the writings of Stopes, whose understanding of science as a positivist and empiricist endeavor, in tandem with her adept use of statistical methods, enabled her to pioneer a modern way to think about sexuality.

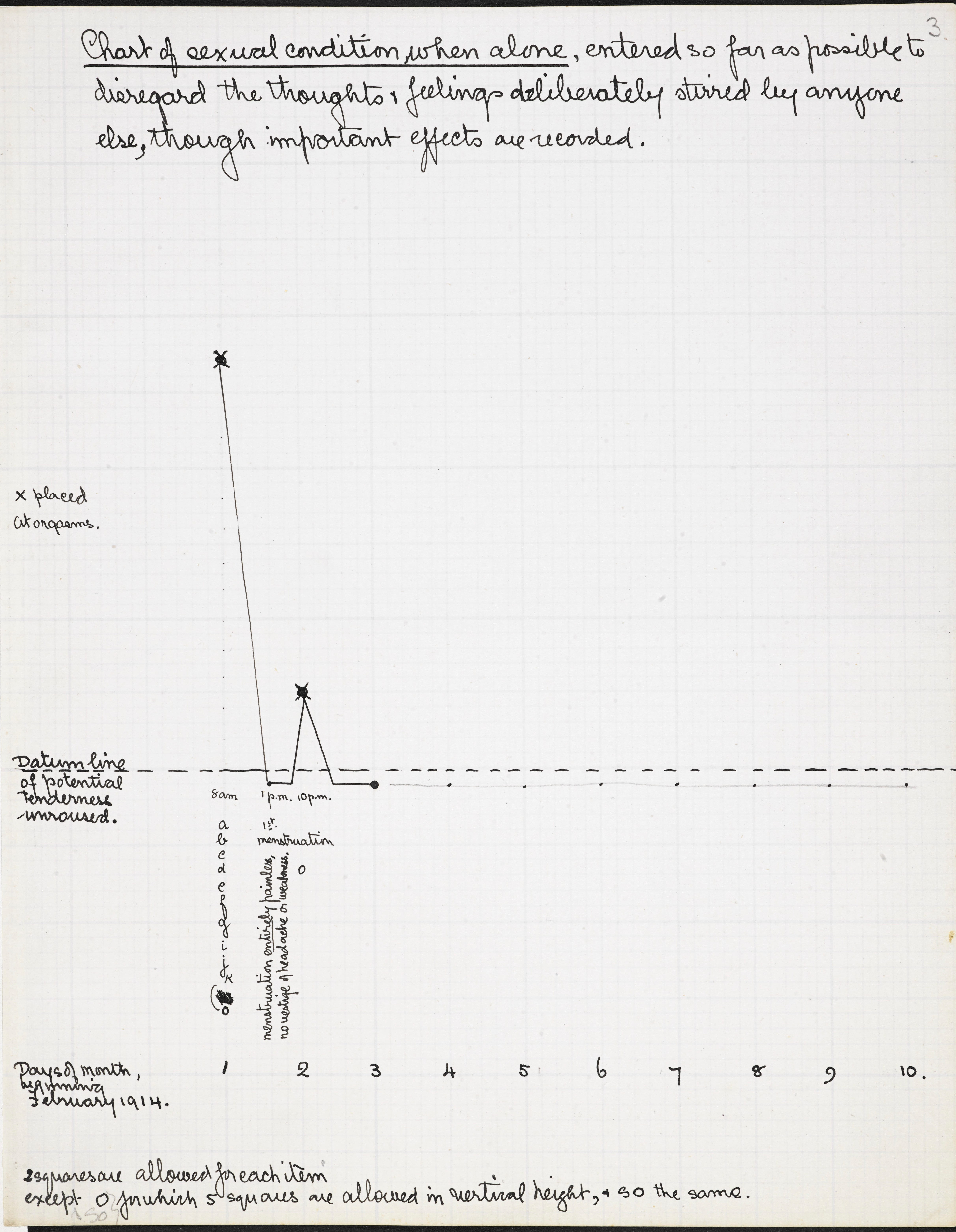

1913 Chart by Stopes

There is now a substantial historiography accounting for the emergence of homosexual practices, identities, cultures, and communities across the globe, yet the story of the rise of heterosexuality is largely untold. I see my own project as honoring a rare contribution to the field by the historian Jonathan Ned Katz, whose important book—The Invention of Heterosexuality (1995)—broke the silence surrounding this most elusive of sexual practices. Unfortunately, historians of sexuality have been slow in building on Katz’s intervention and, consequently, as he puts it: “the “heterosexual norm still generally works quietly, unspoken, behind the scenes.” Such neglect points to a curious lopsidedness in the history of sexuality in which the homosexual possesses a historical presence the heterosexual lacks. Queer theorists have been highly effective in theorizing how heterosexuality secures its power through a perverse symmetry with its lexical counterpart, but detailed historical understanding of how the hetero evolves and establishes its dominance over the homo is sketchy.

With the medicalization of sexuality in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries sexologists required an ideal social norm—called the “normal”—against which perversion, anomaly or deviance might be measured. Conjured into existence through the taxonomical elaboration of the perversions, the normal would become a paradox—hegemonic as an absent presence, lurking obliquely in early twentieth-century references to “regular” sexuality. A product of negative identification, the category of the heterosexual would come to be perceived not for what it is but for what it is not. For this reason, the title of my new book in progress is subtitled “an unnatural history”—unnatural in the sense of what is unusual, unexpected or strange in constructing heterosexuality. I suggest attempts to produce knowledge of a normal sexual subject are inextricably connected to the circuitries of a much older discursive formation which pits the natural against the unnatural, the latter associated with what is irregular or at variance with the usual. To this day, as the historian of science Lorraine Daston observes, the “reproach of the ‘unnatural’ has not lost its sting.” The history of normal sex is full of the unexpected, not least in its resistance to ontology, its appeal to all things “natural,” and its investment—indeed, privileging—of the abnormal, a topic I discuss at length in my article.

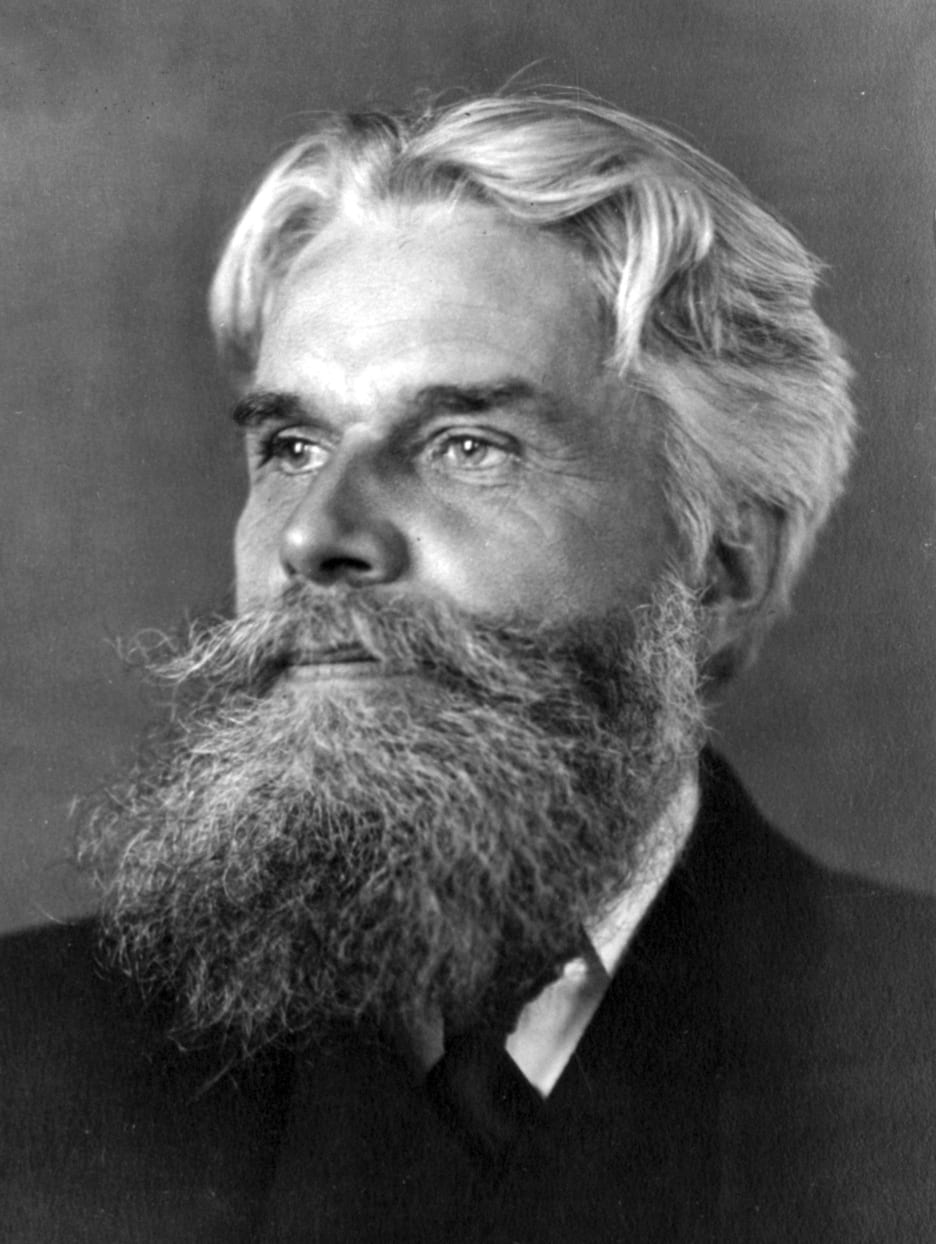

Havelock Ellis (1859-1939)

My main concern has been to investigate the consequences of tethering the normal to Nature, as if the natural order was simply a fact of life. The history of modern heterosexuality begins with investigating the consequences of fusing and confusing the natural and the normal—or, to put it more accurately, historicizing normal sexuality entails looking closely at how the norm of normal became bound up with what was imagined as Nature’s scheme. In the first half of the twentieth century ordinary Britons came to see sexual instincts not only as part of—or contrary to—Nature’s plan but also as normal or abnormal, largely due to the tremendous influence of Stopes’s research on the cyclical nature of female sexual desire. Comparing Stopes’s research methods to those of the well-known sexologist Havelock Ellis indicates the invention of heterosexuality owes more to natural science than sexual science. Often pigeonholed as a birth control campaigner or agony aunt, Stopes should not be underestimated as a central figure in the making of sex as normal. In addressing ordinary people rather than professional colleagues, Stopes turned her readers into collaborators, carving out conceptual space for imagining sexual desire between women and men as a project of scientific interest.

Laura Doan is Professor of Cultural History and Sexuality Studies at the University of Manchester, UK. She is author of Fashioning Sapphism: The Origins of a Modern English Lesbian Culture (2001) and Disturbing Practices: History, Sexuality, and Women’s Experience of Modern War (2013).

Leave a Reply